[Editor’s Note: This article was cross-posted from the PeopleForBikes’ Green Lane Project blog.]

A curbside parking spot is just 182 square feet of urban space. But for advocates of better American bike infrastructure, few obstacles loom larger.

Right now in San Diego, a long-brewing plan to add better pedestrian crossings and a continuous protected bike lane to the deadliest corridor in the city is fighting for its life in large part because some merchants on four commercial blocks don’t want to risk removing any auto parking.

The merchants aren’t wrong that private parking spaces have commercial value to nearby properties. But bike lanes, street trees and better sidewalks would have commercial value too—and creating San Diego’s first comfortable crosstown bike network would also bring value to the entire city, not to mention helping liberate retailers from dependence on car parking.

For cities around the country and the world, converting on-street parking spaces into anything else is one of the greatest challenges in urban planning.

But, though it’s probably never been done without a fight, many cities have succeeded. Here are the best approaches we’ve seen from North America and beyond.

1) Chicago: Recruit allies in advance

When business opposition is likely, a few friends are invaluable. When Chicago wanted to remove parking to create a crucial protected bike lane on Milwaukee Avenue, advocacy group Active Trans identified a retail owner who supported better bike access to his restaurant. He found two like-minded peers and the three stood up publicly for their point of view, countering the stereotype that “business” opposed bike lanes across the board.

“By framing the issue in terms of cyclists vs. anti-cyclists, your coverage overlooks the fact that most city dwellers (and business owners) don’t fit into exclusive categories when it comes to how we get around,” the trio wrote in a letter to the Sun-Times.

2) Montreal: Talk walking distances, not block faces

When people think about removing parking from (for example) one side of a street, the first number that comes to mind is usually “half.” As in “you’re removing half the parking from Main Street, are you completely insane.”

But cities should never talk about parking removal this way—it’s inaccurate. What actually matters to a neighborhood is the number of available spaces within a reasonable walking distance in all directions from a destination.

In 2005, when Montreal was considering removal of 300 parking spaces for one of its first protected bike lanes, planners conducted a survey of every parking space within 200 meters. There turned out to be 11,000. The bike lane moved forward; today it’s the city’s signature bikeway.

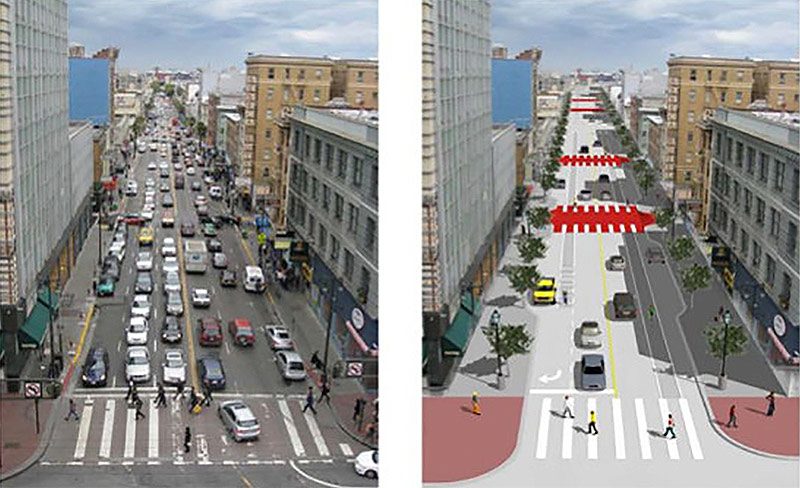

3) St. Paul: Put the ‘parking shortage’ in overhead context

In many cities, there’s nothing like a little aerial photography (starts at p. 37) to get people thinking about whether they’re dealing with an actual lack of space to park in or just a failure to use the space efficiently.

[beforeafter]

[/beforeafter]

[/beforeafter]

[Images: Portland Mayor Charlie Hales, left, plays ping pong on SW 3rd Avenue, Portland. After view by Greg Raisman.]

4) Portland: Demonstrate what else is possible

For years, one of the top tourist attractions in Portland, Oregon, has been a 24-hour doughnut shop with a line that wraps onto the sidewalk in front of a disintegrating porn theater.

The street is wide there—wide enough for three one-way mixed traffic lanes, angle parking on one side and a loading zone on the other. But in 2014 a group of local businesses and streets advocates realized that traffic was so low there that only a single lane of auto traffic was needed. So for three days that fall, they got the city’s permission to temporarily replace all the parking and two general travel lanes with a protected bike lane and a massive new plaza filled with hay-bale seating—and, during the day, ping-pong tables.

Hundreds of people showed up to enjoy it. Traffic on the block flowed smoothly. Businesses flooded with customers. The Oregonian newspaper called the event “the future of Portland.” A few months later, businesses scored a grant to create a permanent plaza in the space and are working on long-term plans to permanently redesign the street.

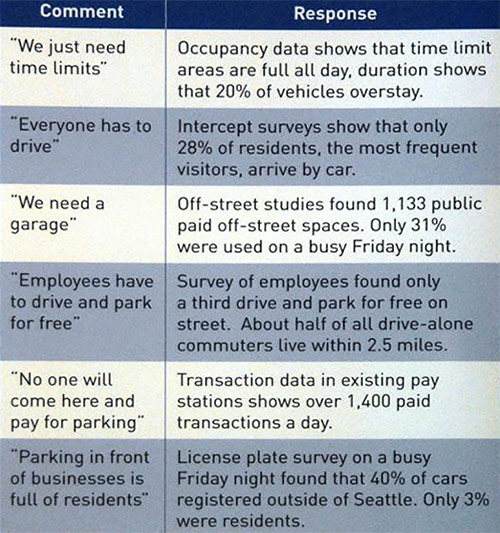

5) Seattle: Gird your loins with data

Seattle has removed a few dozen of its hundreds of thousands of auto parking spaces this year for the sake of protected bike lanes and bus improvements. That’s coincided with a new demand-sensitive parking reform that helped generate enviably hard numbers about the ways people use (or don’t use) car parking. This detail from a poster by city transportation planner Jonathan Williams is a nice example of data gathered and chosen to defuse common concerns.

6) Frankfurt: Charge for curbside spaces what they’re worth

Here’s a riddle: How can a city turn the empty spaces in its downtown parking garages into a bike lane?

As the Seattle data above suggests, off-street parking is often underused, despite the colossal expense of building it. Why? Because curbside parking is much more convenient, of course. A reasonable response, embraced by Frankfurt in 2013, among other cities: Price on-street parking like the premium product that it is, raising the price until people choose the unused, affordable off-street spaces instead. If that leaves empty spaces on the street, well, we bet there’s a way to put them to public use.

7) Utrecht: Make garages easy

The Netherlands didn’t become the world’s best country to bike in by making itself a terrible place to drive. Its national freeway system is also among the world’s finest.

But when freeways approach cities, they pull out every stop to help people find their way to garages that let them ditch their cars and enjoy Dutch cities the easy way: by transit, bike, and foot.

“When you take the A to get into downtown Utrecht, while you’re still on the freeway there are signstelling you ‘here are the parking garages and here are the spaces that you have available,’ said Zach Vanderkooy, who leads tours of Dutch bike infrastructure for PeopleForBikes. “They definitely provide a lot of car parking, but they go to great expense to keep people from needing to struggle to find it.”

8) San Francisco: Ask all residents what they think

Most municipal public outreach is inherently unrepresentative. If tenants, low-income residents and non-English speakers aren’t showing up to public meetings in accurate proportion, a city shouldn’t pretend their interests are actually being heard.

So what’s a city to do? In one poor San Francisco neighborhood, the city supervisor worked with a group that specializes in organizing low-income residents to conduct direct surveys of what they wanted on their street.

Probably because car parking spaces are useless to most low-income San Franciscans, the neighborhood consensus was clear: more than two-thirds said that transit, walking and biking were higher priorities than auto parking.

9) Mexico City: Show the big picture

The case for adding auto parking to a city makes perfect sense until approximately two minutes after you start thinking about it. Two weeks ago in Mexico City, research group ITDP Mexico released a wonderful video (complete with English subtitles) that walks its viewers through those two minutes of critical thinking and toward the suggestion that what we really want is menos cajones, más ciudad—less parking, more city.

10) Vancouver: Grit your teeth and wait

We’ve saved our favorite story for last.

In 2013, Vancouver, B.C., proposed adding protected bike lanes to a single block of Union Street, a crucial connection between two of the city’s most important bikeways: the Adanac bike boulevard and the Dunsmuir viaduct into downtown’s protected bike lane grid.

But adding bike lanes there would require moving several dozen street parking spaces onto nearby Main Street — so the city faced a firestorm from retailers and residents.

“To slash and burn like this is not going to work,” Steve Da Cruz, owner of an upscale restaurant in the middle of the affected block, told the Vancouver Courier.

In the end, the city removed about 20 spaces from Union in order to create a parking-protected bike lane in the westbound direction only. And in the three months that followed, Da Cruz’s fears came true: his sales dropped 30 percent, he said.

Then something happened that he didn’t expect: business rebounded. With the upgraded bike lane, more people were streaming past his storefront than ever. One year after installation, Da Cruz told Business in Vancouver that his restaurant was doing better than ever.

“We definitely have benefited from the increased usage of the bike lane,” Da Cruz said.

“It’s beautiful when you ride by now,” said Erin O’Melinn, executive director of the HUB biking advocacy group. “The bike racks are just busting. They’re so full and they’ve added more since the installation of those lanes. They’re always overflowing.”

Winning a parking war requires every tool and ally a bike believer has. But in the end, there’s no more powerful ally in the world than reality.