On June 29, 1955, the Courier-Journal published an editorial accompanied by a photo of Rotterdam after it was destroyed by bombs during World War II. “Bombs falling on crowded Fourth Street—that is a horrible thought to Louisvillians,” the editorial began. But this lament wasn’t a plea for world peace or the documentation of a tragedy a decade earlier. It was a call to destroy and rebuild Downtown Louisville.

The editorial was titled “A Bomb at Fourth and Walnut That Would Bless Louisville.” (Today, Walnut Street is Muhammad Ali Boulevard.) It grimly concluded that “The old shell of downtown Louisville will have to be cracked open if real progress is to be made. We don’t want it done by the violence of enemy bombs, heaven knows. But another kind of bomb falling on Fourth Street would be a blessing—a bomb of imagination and civic ambition.”

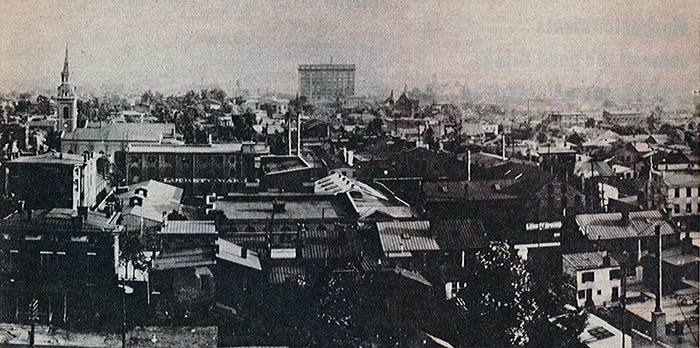

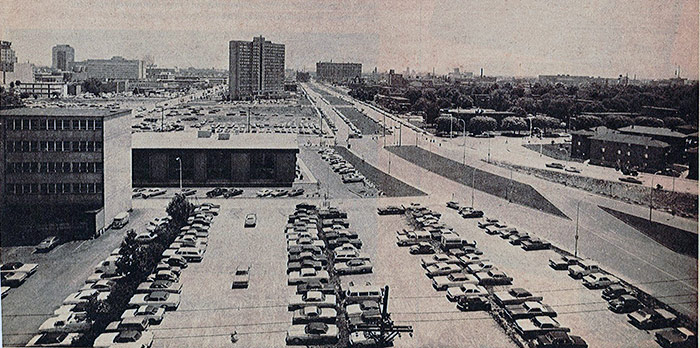

(Above: A view looking south from the Glassworks building before urban renewal circa 1926 and the same view after clearance in 1976.)

Today, many urbanists compare the fate of American downtowns to the bombings of World War II. Locally, we’ve called it “urbicide” for its thorough job in eradicating the urban landscape. But rarely, if ever, do we see a city’s major newspaper actively calling for bombing its downtown, either literal or metaphorical. But that was the sentiment toward Louisville’s grand architecture in the middle of the 20th Century. And it has ended up a rather accurate prediction of what would unfold in Louisville in the following three decades of urban renewal, highway building, poor planning, and a lack of concern for preservation.

“Those of us who have lived here a long time love it because it is familiar and friendly,” the editorial stated, quite oversimplifying what makes Louisville a loveable place. “But we must not let ourselves be blinded to the fact that it is also cramped, out of date, and inconvenient in many ways.”

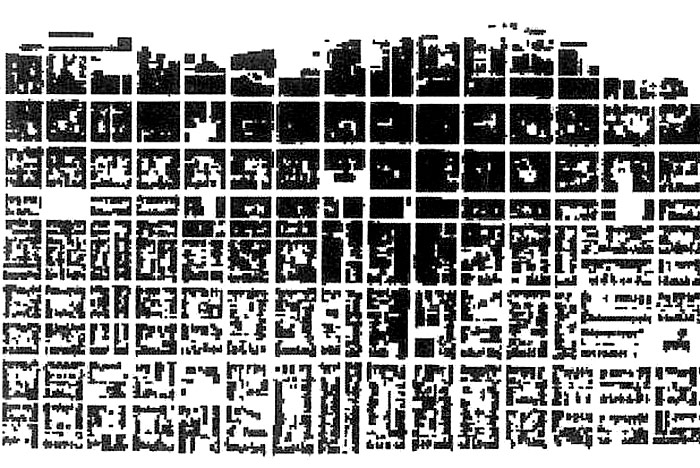

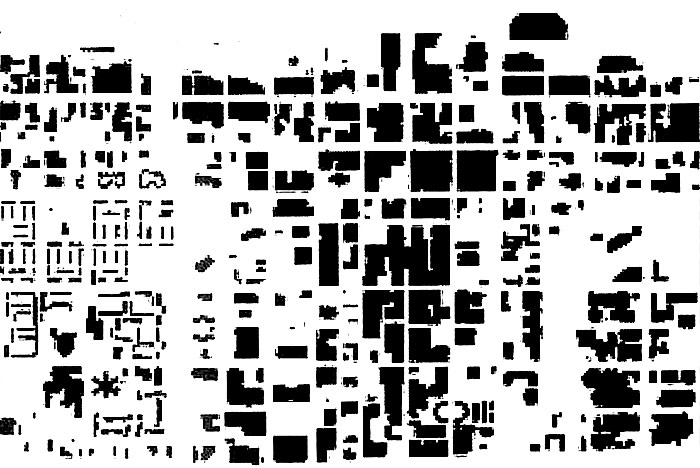

(Above: A figure-ground map of Downtown Louisville circa 1900 and again in 1990.)

Once Downtown had been cleared, the newspaper made a call for rebuilding in a modern way—one that would rid the city of dirty old buildings and make plenty of room for the automobile. It made the call for a new modern aesthetic using a rather sexist argument, to boot. And the prevailing notion of what would make Louisville “modern” was a pedestrian mall along Fourth Street proposed in 1955 by a college student at Yale.

“These [European, bombed-out] cities have made a virtue of necessity in the costly job of reconstruction. All have rebuilt along the newest lines of city planning,” the editorial noted. “In every case, a principal new feature has been a retail center in the heart of town, designed for the special needs of shoppers, with vehicular traffic barred, and with shrubs, trees and flowers to give a feeling of pleasant space.”

The newspaper predicted that if Louisville took such drastic action, the city would “grow dramatically in the next couple of decades, probably passing Cincinnati and Indianapolis.” It warned that not bombing Downtown Louisville could lead to a stagnant economy. “The one thing Louisville cannot do is stand still.” That’s a line we still hear today.

In the end, Louisville did bomb itself into a parking lot oblivion, but unlike those European examples cited in the newspaper, we put too much faith in the private automobile and didn’t rebuild after the bombings. Our pedestrian mall was was a failure because it relied on a suburban notion of shopping and driving rather than living in the core city. Much of urban renewal had ulterior motives that better served keeping the city segregated than any true attempt to craft a better Louisville.

Back in the ’50s, however, the city had no idea how these untested ideas would play out, and shiny visions of modern cities as an automobile utopia seemed logical at least on paper. There were no sprawling suburbs, no shopping malls, no massive highways slicing through urban neighborhoods, and no clear-cutting of the urban fabric. There was an intact city that still clung to its dominance as the region’s premier shopping center, although it was quickly showing its age. And in the techno-futuristic mid-century, anything was possible with a little elbow grease and imagination. Or “bombs of civic ambition.”

Sigh. And sad to say a lot of this bombing has indeed occurred. Fourth and Broadway……….Fourth and Walnut……Fourth and Jefferson………

The Galleria/Fourth St DeaderAlive is possibly the worst idea since River City Mall.

Ain’t larned much…….

To bad we didn’t learn from what Europe ended up building. I always think of Le Havre when I think of great exapmles of recently designed very walkable, livable cities.