I’m rarely on Poplar Level Road, and must admit I’d not really noticed this building before.

It’s part of the Holy Family campus in Louisville’s Camp Taylor neighborhood, whose modern sanctuary is readily recognizable by its copper-topped tower.

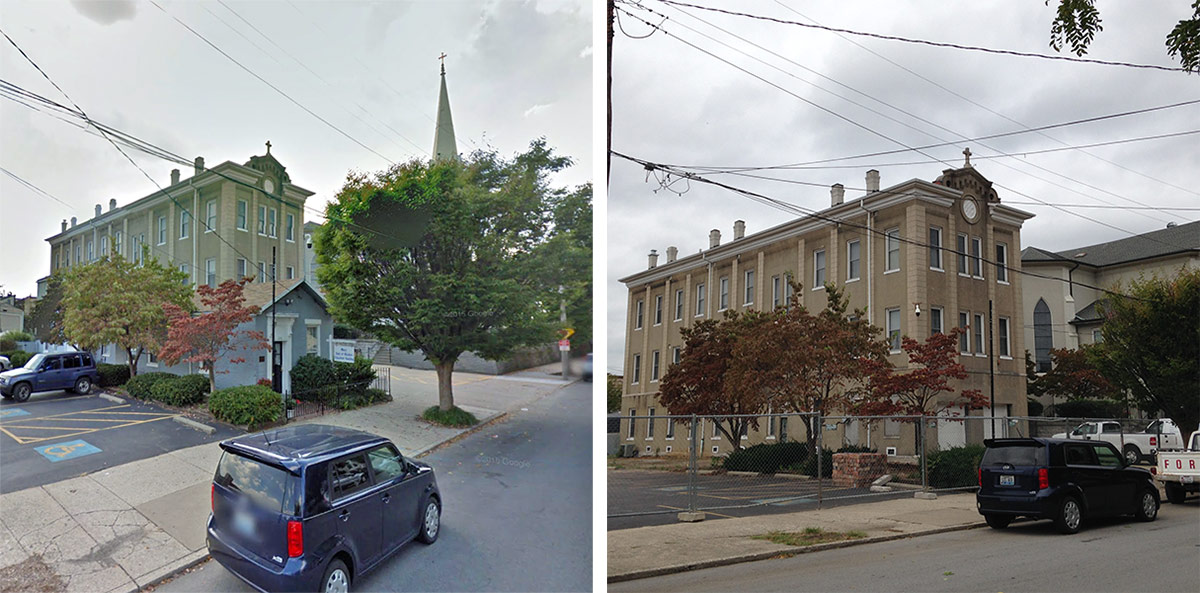

Just south of this newer landmark is the recently-shuttered circa 1952 Holy Family School, built onto the front of a much older school building. Beyond that is the former Holy Family Convent, built in 1950 and most recently enlisted as the Holy Family Child Development Center.

That convent, 3940 Poplar Level, cost $82,000 when it was built in 1950, replacing a wood frame structure that may have been part of the original World War I barracks at Camp Taylor. The structure was designed by Louisville’s Thomas J. Nolan & Sons Architects to house 20 Sisters of Charity of Nazareth. The brick and stone-trim structure was officially blessed by Reverend D.A. Driscoll, rector of the Cathedral of the Assumption, on January 7, 1951.

These latter two buildings are now owned by the Catholic Archdiocese of Louisville, and are soon to become this entity’s new central headquarters, once relocated from their present offices at 212 East College Street in Smoketown.

The Holy Family School, beloved by former students and their families, and familiar to all who live within or pass through Camp Taylor, will be renovated and reused. But the fate of the convent, called locally the Nuns’ Home, is not so rosy, as made rather obvious by the yellow excavator currently parked out front.

A fair number of us Louisvillians have grown weary of the sight of demolition machines, as have so many others, over decades of demolition around the city. But as those years have marched by, redevelopment practices that once might have been considered misguided could now be considered irresponsible.

Because here’s the deal. We know better now.

This example out on Poplar Level is but one of a multitude of demolitions that will occur this year across the city. And while the Archdiocese certainly is not alone in swinging the wrecking ball, it’s been only months since the last church-owned property was unceremoniously taken down.

In July 2015, a nice brick shotgun house on Gray Street in Phoenix Hill was demolished around the corner from St. Martin of Tours Church on Shelby Street.

But to be fair, we must recognize that the Catholic Church in Louisville does maintain numerous historic structures, many of which are treasured landmarks. For that, credit is most certainly due. And even on Poplar Level, one of the two structures—the Holy Family School—has been granted a new lease on life.

According to the Archdiocese’s spokesperson, Cecelia Price, the initial goal in the project at Holy Family was to renovate and incorporate both the School and the Nuns’ Home into a connected headquarters building. But the latter building’s structure and configuration was deemed unsuitable, and the decision was made to demolish and replace with a modern, energy-efficient building. There’s even mention of a green roof. (No renderings were available as of press time.)

But here’s the rub.

Rarely does a newly-built, energy-efficient building surpass the environmental benefit of reusing an existing structure. Take a look at the most comprehensive study to date of the sustainability of preservation and reuse, published by the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Preservation Green Lab, the same organization that has made Louisville one of its primary workshops in its efforts to integrate preservation and sustainable building practices.

From that document, when the Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) of a structure—i.e. its total environmental and human health impact, all things considered—is tallied, several simple conclusions can be made from the data:

- “Building reuse almost always yields fewer environmental impacts than new construction.” And the savings here can be huge—up to 46 percent—when comparing a reused vs. newly-built structure with the same intended use (as is the case in the example of the Holy Family site).

- “Reuse-based impact reductions may seem small when considering a single building. However, the absolute carbon-related impact reductions can be substantial when these results are scaled across the building stock of a city.” In the case of Portland, Ore., reuse instead of demolition could account for 15 percent of the total carbon reduction goal over a period of ten years. That’s significant.

- “Reuse of buildings with an average level of energy performance [i.e. the Nuns’ Home] consistently offers immediate climate-change impact reductions compared to more energy-efficient new construction.” We know that demolition wastes the non-recoverable embodied energy of an existing building. But the data also suggest that a period of 10 to 80 years is required to recoup the losses, too, of constructing a new, 30 percent more energy efficient building.

Or, in simpler terms, a common but oft-ignored refrain: The greenest building is the one still standing.

Isn’t it time for Louisville, which struggles to maintain even a modicum of sustainability, to take heed?

A thought provoking article.

Preservation isn’t just about high style museum pieces. It’s taking what you already have and making more of it than the sum of its parts might first suggest. You can put all the solar panels on it you like; the embodied energy lost is staggering X 10.

This is a building with life still in it. And my guess is, it would be a lot less money to reuse it and add to it. Or turn it into affordable housing . Very shortsighted but unfortunately religious institutions and institutions of higher learning are notorious for this backward approach.

Thanks for the article.

Thanks Bryan for following up on this! Hopefully Metro Councilman Pat Mulvihill will watch for the Archdiocese’s proposal for what will replace this landmark of the Camp Taylor, Poplar Level and Audubon Park neighborhoods.

Preservation/reuse of an existing building is a great approach when the building can be made usable for the purpose. Many preservationists don’t ever consider economics when they cry about the demolition of the building. You need to realize that businesses (yes the archdiocese is a business) need to be responsible about how they spend money on projects. They can’t ignore cost considerations just to preserve a building because members of the community want it preserved.

In this case the fact that the building is no significant architectural significance also needs to be taken into account.

You’re certainly correct in your observations about the short-term economic considerations in cases such as these. I’d wager that a fair number of those crying preservationists recognize this, as well. Further, it certainly can be argued that this building is not even particularly historic, though that depends upon one’s definition. This post, therefore, tries to pivot away from preservation and from singling out the Archdiocese, and focuses more on the greater question of sustainability in our overall building practices — both in Louisville, and nationwide. In my mind, we’ve got to take the higher long-term costs of the endless cycle of demo-rebuild into greater consideration.