(Editor’s Note: This article is part of a series we’re running on Broken Sidewalk in honor of National Preservation Month 2016. We’ll be looking at the histories of significant structures, some that are still with us and many that are gone, in an effort to better understand Louisville’s history and built environment.)

Google “Lakeland Asylum” and “Louisville” and you’ll find ghost stories, spooky photos of its remaining underground tunnel, and any number of the same facts and figures repeated over and over again. In May, which happens to be National Preservation Month as well as Mental Health Awareness Month, we acknowledge both to explore the history of a Lost Louisville landmark, the historic Central State Hospital, more commonly known as Lakeland Asylum.

When it opened in 1873 with 50 residents in Anchorage, ten miles outside the city center, Lakeland wasn’t the first asylum in Kentucky. It wasn’t even the second. No, the fourth Kentucky asylum, called Central Kentucky Lunatic Asylum at the time, was formerly the State House of Reform for Juvenile Delinquents. Built around 1868 or 1869 on land sold to the state by the family of pioneer Isaac Hite, the House of Reform took in white male and female children between the ages of seven and sixteen. A report from the Journal of the Senate in 1869 stated that the children were “legally committed” as “vagrants, or on a conviction of any criminal offense less than murder.” It is unclear what happened to the children once the facility was converted into an asylum barely four years later.

According to its National Register of Historic Places application, the architect of Lakeland’s original hospital building is unknown. However, “John Andrewartha, a Louisville architect who designed City Hall, was consulted in 1874 on extensions and additions to the hospital.”

Designed loosely in a Kirkbride Plan, with long, multiple-story wings radiating from a central administrative tower, Central State was an imposing building of red brick, narrow arched windows, towers, turrets, and crenellations worthy of adorning a medieval castle. The wards were segregated by gender and race, but not all of the patients had mental illnesses. Some suffered from neurological disorders or were disabled. Sadly, others were just poor, elderly, or didn’t have any other family to take care of them.

At the time, doctors believed that pleasing architecture and picturesque landscapes were part of the cure for mental illness. Also, while a rural location limited exposure to pollutants and large groups of people, it may have endangered fewer people if residents escaped. An 1875 legislative document remarked “escapes are not always avoidable, even with the most careful surroundings and the most rigid surveillance.”

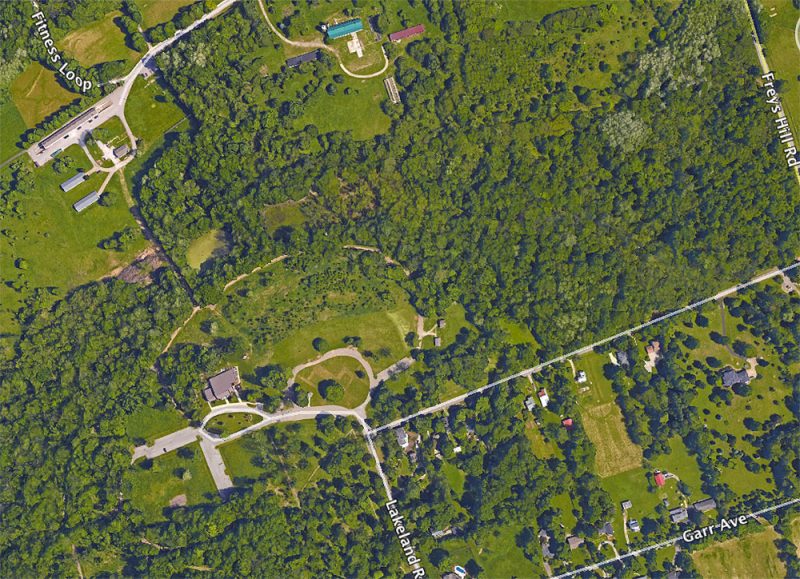

The surrounding land on the hospital grounds grew to over 500 acres by 1913. Eventually it “housed a power plant, a water treatment facility, a dairy barn and farm house area, botanical gardens, water tower storage, and many other facilities,” according to the History Hike information provided by E.P. “Tom” Sawyer State Park. A dedicated post office opened in 1887 and a train depot in 1892. Self-sufficiency was the goal, and residents at the hospital often worked on the farm or in other capacities. It was believed that participating in chores gave residents a sense of purpose and responsibility. An entertainment hall provided a safe, controlled environment for games and other recreational activities.

Newspaper reports as early as 1879 described crowded conditions—these overcrowding reports would continue for decades—and by 1895 the hospital’s population had grown enough to warrant construction of two new wards. More buildings were added over time. In 1900 the name changed to Central Kentucky Asylum for the Insane, with the final name change happening in 1912 to Central State Hospital. Major renovations in the 1950s changed the facades of the projecting wings on either side of the central administrative building.

A history document produced by the Central State Hospital system describes how the approach to mental illness changed over time. “By the mid 1930s, the facility offered an array of treatment, including hydrotherapy, insulin shock treatment, sedative tubs, electroshock-convulsive therapy, and lobotomies,” similar to other mental hospitals at the time. “In the 1950s, antipsychotic medications and tranquilizers were developed and replaced the earlier, more primitive methods of calming and stabilizing patients.” The Community Mental Health Centers Acts of 1963 and 1965 “resulted in a new approach to treatment, which emphasized de-institutionalizing patients by treating them in the least restrictive environment in which they could effectively function.”

After Medicaid was adopted in 1965, the de-institutionalization of state-run mental hospitals accelerated. Then in the 1970s, the state donated 400 acres of land for the creation of E.P. “Tom” Sawyer State Park. The hospital’s main administrative building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1983, but three years later, patients were transferred from the historic hospital building to a new location on La Grange Road. After languishing empty for nearly a decade while discussion on possible future use took place, the state ultimately demolished the hospital in 1996.

When pulling up to the former location of the hospital on a gray day this past February, this writer could almost feel her mother’s shudder from across the car. As a student nurse in the 1970s on her psych rotation, she remembers feeling terrified to work there, to be locked in a ward with the other nurses and patients. I asked, “So the building was there, looming there on that hill?” She paused and said, “Yes, looming was a good word for it.”

For more information: The Recreation Office at E.P. “Tom” Sawyer State Park maintains a collection of papers, photos, and other information on the hospital, as well as offering a History Hike through the grounds. There is an interpretive marker near the site with a few faded photos, and several relics found on the hospital grounds during demolition are displayed in cases in the recreation building. Also, Samuel W. Thomas’ book The Village of Anchorage has an entire chapter on the Lunatic Asylum at Lakeland. Additional photos can be viewed here.

[Top image of an early postcard view of Lakeland courtesy UL Archives – Reference.]

Nice article. Snuck in there as a kid living in Anchorage many times..scary place.