Road space needs to come from somewhere. And with the nation’s infrastructure budgets buckling under road maintenance costs, there’s growing consensus that ever-wider roads are infeasible.

Instead, a large and bipartisan majority of U.S. mayors agree, cities should be taking the opposite approach: making their entire systems more space-efficient, cost-effective, and economically productive by adding bike facilities in place of extra passing lanes or on-street parking spaces.

That’s according to the 2015 Menino Survey of Mayors, released this week by the U.S. Conference of Mayors. The survey was of 89 mayors from “cities of all sizes and affluence.”

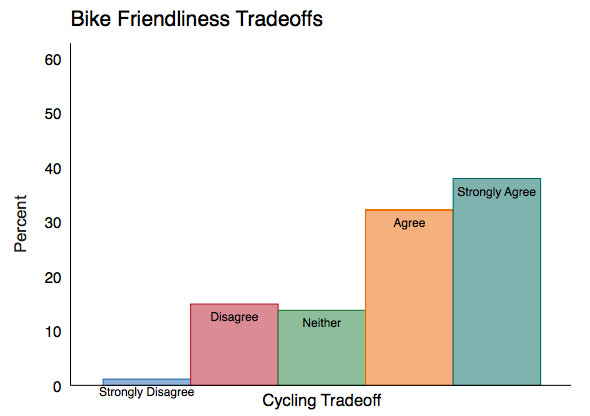

Here’s the relevant survey question:

That’s 70 percent of U.S. mayors who believe that biking networks are important enough to U.S. roads that it’s worth converting parking and driving lanes to make room.

This strategy for connecting bike networks into a usable “minimum grid” (to borrow a phrase from our neighbors in Toronto) isn’t just about bike infrastructure. Removing passing lanes, as Indianapolis did to create its downtown Cultural Trail, can lower auto speeds. Removing street parking, as Salt Lake City did to create its first downtown protected bike lanes, can actually help a district become less dependent on parking for its economic success by improving the alternatives to driving.

Both of those projects, which also went hand in hand with big improvements to walking, led to significant upticks in retail growth and neighborhood investment.

Democratic mayors overwhelmingly prioritize biking, while GOP splits evenly

“Cycling infrastructure emerged as a strong priority for mayors, garnering strong support overall and support — albeit in varying degrees — from mayors of both parties,” the Conference of Mayors wrote in its analysis of the new survey.

There was a clear divide between Democratic and Republican mayors. About 80 percent of Democratic mayors agreed with the statement about prioritizing biking improvements over the status quo. GOP mayors split on the question 43 percent to 43 percent, with the remaining 14 percent undecided.

One in five mayors puts “bicycle friendliness” among top three infrastructure priorities

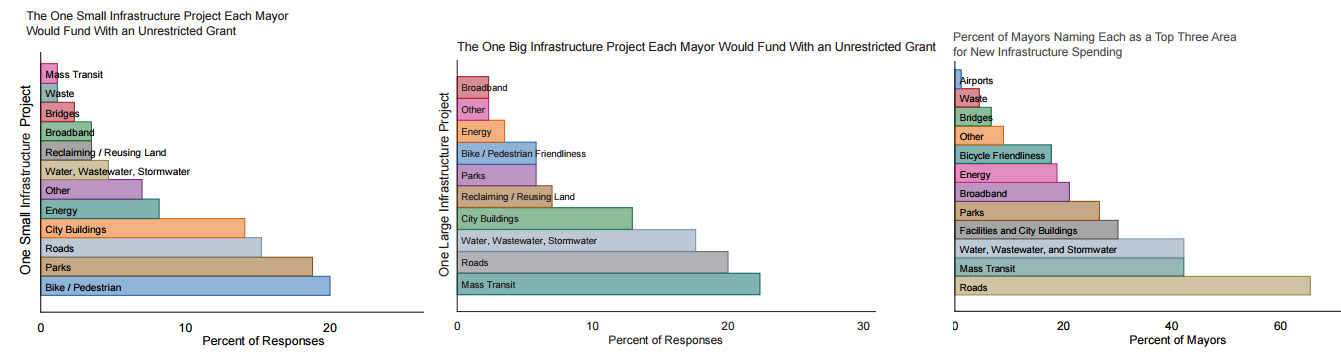

The survey also asked mayors to say what they’d do with a pair of unrestricted infrastructure grants: one “small” and one “large.”

For the “small” grants, biking and walking investments came in first. They topped parks, roads, city buildings, and eight other possible infrastructure investments as low-cost, high-return projects.

“Interestingly, responses did not vary significantly by city size,” the report noted.

For a hypothetical “large” infrastructure grant, biking and walking rated as lower priorities, though the generic “roads” answer came in a close second to mayors’ single most common priority: “mass transit.”

And when the survey asked mayors to name their top three areas for new infrastructure spending, one in five of the mayors surveyed said “bicycle friendliness” was in their top tier.

Mayors are unique among almost all government officials in the breadth of issues they must care about and the depth of knowledge they must have about their city. So maybe it’s no surprise that biking investments tend to stand out to them as good ideas: they reduce public transportation costs, recruit young workers, clean the air and boost public health.

Not everyone in cities sees how those benefits fit together on city streets. Then again, few people see cities the way good mayors must.

[Editor’s Note: This article was cross-posted from PeopleForBikes’ Green Lane Project blog. Follow them on Facebook and Twitter.]

I know a lot of cyclists argue that it’s safer for cyclists to ride with traffic rather than in dedicated bike lanes, but is there something to be said for the effect of having a painted bike lane which eliminates then narrows another lane to calm traffic, rather than having a wide open speedway? I’m thinking about Kentucky Street, where the bike lane eliminated a lane and seems to have slowed down cars substantially? Two way would be better but until that happens it seems like the bike lane and buffer is having a positive effect.

Wayne, I recognize that the Kentucky Street bike lane gives the illusion of traffic calming.

I also recognize that many conflate “having a quieter experience” with “being safer on their bicycles.”

I love having quiet networks of streets to use for my cycling transportation. The thing is, we want to connect quiet networks of streets with other quiet networks of streets. The problem is how to do that.

What valid research has found (contrary to the junk science published by K. Teschke, Anne Lusk, and others of their ilk) is that cyclist safety is largely a function of cyclist behavior, with the goal of the behavior being relevance to other road users (in cooperation as part of traffic, which is a concept that cannot be boiled down to a single sentence).

Edge-of-pavement or on-street bike lanes do one thing exceptionally well: They make cyclists and motorists irrelevant to one-another until moment of impact, which is usually in or near an intersection that is more complex than it should be because of the on-street bike lane.

Sadly, the writers at Broken Sidewalk (along with just about the entire board of Bicycling for Louisville) lack the intellectual integrity to understand this.