[Editor’s Note: The next chapter of the Louisville Armory, aka the Louisville Gardens, is beginning to unfold as Underhill Associates reveals their proposal to rehabilitate the circa-1905 structure. This history of the armory was originally published December 8, 2009 on the Scotty Moore website, which chronicles the history of the hall-of-fame guitarist who notably played with Elvis Presley. This article appears here with the permission of James Roy, who administers the site, and has been updated to fit the editorial style of Broken Sidewalk. Please add your own memories of the building in the comments below.]

The Early Days

“Plans for the Louisville Armory actually began in 1893, when the state legislators passed a law

that required every city of 1st or 2nd class to provide an armory with a drill hall and ammunition

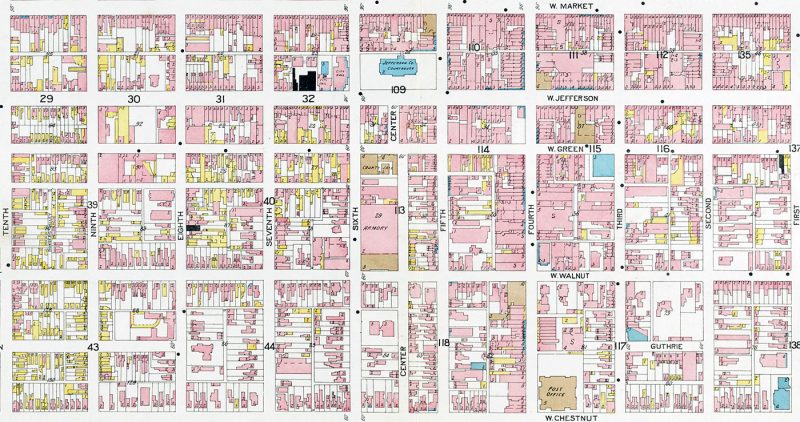

repository for the local branch of the state militia,” wrote Kate Carothers in her 1999 report to the National Register of Historic Places. As it was not always possible to build a new armory, some towns adapted existing buildings which were adequate to meet the needs of the National Guard. In Louisville, a large plot of land was purchased in April of 1904 at the corner of Walnut Street (now Muhammad Ali Boulevard) and Sixth Street from O.S. Basye and Company for $89,750.10 Originally it was the site where Aleck and Annie Craig’s Louisville home once stood.*

According to the state’s history of the Kentucky National Guard:

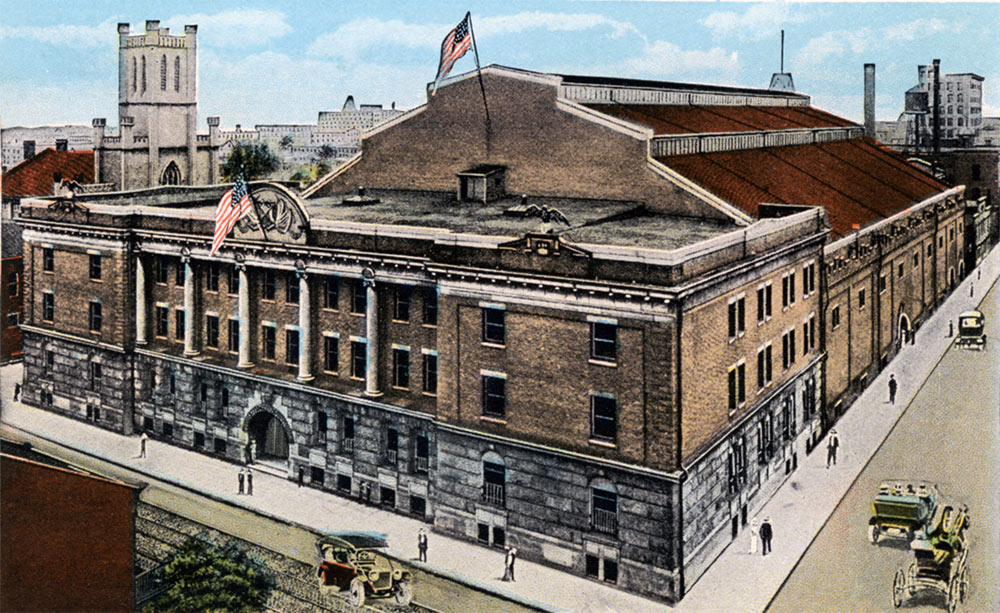

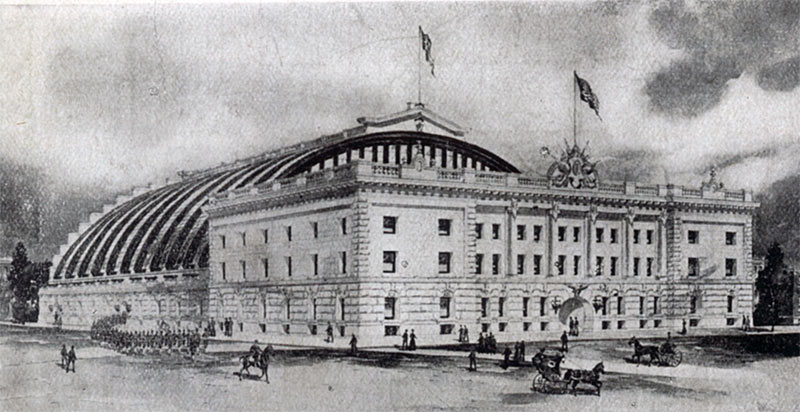

The old armory, now Louisville Gardens, is a large three-story brick, stone, and steel building on a raised basement. It was designed by Louisville architect Brinton B. Davis, and built by the Louisville firm of Caldwell & Drake. The building was designed in the Beaux Arts style, and featured eagles perched atop the facade, cannons along the cornice line, and an arched entranceway. The raised basement/foundation was built of rough-cut stone. The building cost a total of $440,000 to build, and it was largely finished and dedicated on December 31, 1905. An estimated 10,000 people attended the dedication ceremony. Although its main function was that of a military installation and arsenal for the famed Louisville Legion, later part of the Kentucky National Guard, the building was also intended as a community center for the City of Louisville, which did not have a large meeting/ recreational facility at the turn of the century.

The armory included offices, a swimming pool and a rifle range in the basement, a 53,000-square-foot drill, a gym, bathrooms, a band room on the second floor, and locker rooms on the third floor. The Kentucky State history continues:

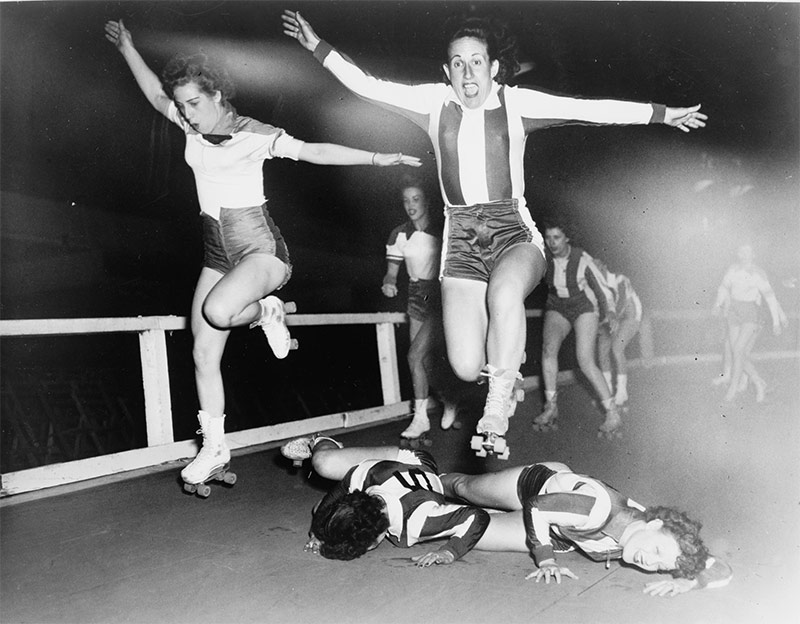

From the beginning, the armory served as a popular recreational and community gathering place. Sports activities such as basketball, tennis, badminton, roller skating, and ice hockey (a large sheet of ice was placed on the drill hall floor for a time) all took place there. Roller derbies and rodeos were other popular events which occurred at the armory. In addition, the Kentucky Horse Show Society held events there, and after 1945, the armory was home to the University of Louisville basketball team. In 1945, the Southeastern Conference was held there.

Notable Guests

According to the Encyclopedia of Louisville, on November 8, 1911, President William Taft made a brief address at the armory advocating his policies looking toward international peace. The following year, ten thousand citizens attended a memorial service at the Armory following the Titanic disaster in 1912. “Numerous entertainment acts graced the Armory’s stage, including Ray Charles, Louis Armstrong, Frank Sinatra, Mary Wells, Igor Stravinsky, Elvis Presley, Stevie Wonder, Bob Dylan, Aaron Copland, and a national broadcast of the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra in 1936,” the Encyclopedia noted. During the Ohio River flood of 1937, the armory provided shelter for six thousand refugees.

The Sporting Life

On January 5, 1937 the University of Kentucky played Notre Dame at the armory, according to Kentucky Wildcat Basketball, in front of 6,352 spectators (the first of many meetings). “This crowd was the largest to see a basketball game in the state of Kentucky up until that time, and far larger than UK’s Alumni Gymnasium (the gym that UK played their home games) could accommodate,” the website noted. From 1941–1952, the armory hosted the Southeastern Conference men’s basketball tournament.

“Over the years, community, sporting, and recreational events had eclipsed the building’s main function as the home of the National Guard,” the state’s history page continued. “The sheer number of activities which were held at the armory forced the Guard to find another location to drill on Sixth Street.” The Guard moved out of the armory in 1946, first to facilities at the fairgrounds and later elsewhere in the county.

Roller Derby at the Armory

Leo A. Seltzer is credited with inventing the sport in 1935, initially as “an endurance exhibition where skaters circled on a track traveling the equivalent distance of skating from coast to coast,” according to Sacramento’s Sacred City Derby Girls. “While this version of derby did prove to be popular, Seltzer quickly noticed that the spectators really enjoyed when the skaters made contact with each other and the crashes that ensued. In 1937, Leo Seltzer re-launched Roller Derby as a full contact sport, played on a banked track with teams competing against each other for points.”

In 1945, Seltzer signed a 15-year lease on the armory as the Kentucky National Guard moved out, according to a 1949 account in The Billboard. Later, Irving Wayne, manager Seltzer Enterprises, helped bring the Polack Bros. Circus to the armory, setting several more attendance records.

Presidential Stature

On September 30, 1948, President Harry S. Truman spoke at the Armory while campaigning during the 1948 Presidential elections, what would be considered the greatest election upset in American history. His 9:00p.m. address was carried on a nationwide radio broadcast. So sure was he expected to lose that The Chicago Tribune erroneously announced his defeat by Republican candidate Thomas E. Dewey. The paper was printed before all the votes were counted.

Elvis Plays the Armory

On November 25, 1956, Elvis Presley, guitarist Scotty Moore, bassist Bill Black, and drummer DJ Fontana made their second appearance in Louisville when booked to perform two shows at the armory. They had performed a year earlier in Louisville at the Rialto theater a few blocks away in an unadvertised show show for Philip Morris employees. By this time, though, they were national news, had been on network television, and Elvis had completed his first movie, due to be released days before the show, at the very theater they performed at the year before.

While Love Me Tender may have been playing at the Rialto, it didn’t stop other businesses in town to capitalize on the excitement of the Elvis craze. RCA was plugging the show and record sales down the street from the Rialto, the Ohio Theater, across the street, offered free 8×10 photos to the first 500 adults to show up to see an Abbott and Costello double-feature. In addition to selling tickets to the shows, Gay’s Department Stores were giving a free ticket away to a show at the armory with any purchase of $9.95 or more.

As excited as the fans were that Elvis was coming to Louisville, there were other factions that didn’t share in the enthusiasm and saw the occasion as cause for concern. Coincidentally, Bill Haley and the Comets were scheduled to appear at the State fairgrounds across town the same day as the armory shows. They had received reports reputedly of rioting in other parts of the country as a result of “simultaneous” rock and roll performances.

On November 7, the chief of the Louisville Police Department, Colonel Carl E. Heustis, contacted the regional FBI field office in Louisville requesting any information on how to prevent any riots that might occur there, fearing a competition between Haley and Presley camps for “the attention of Rock and Roll fans.” The regional office contacted Washington and Hoover responded saying they had no more information on the riots and that they be “tactfully suggested” to consult with the local police chiefs where the riots supposedly occurred. It was not the first time, nor would it be the last, that the FBI had been contacted regarding Elvis Presley.

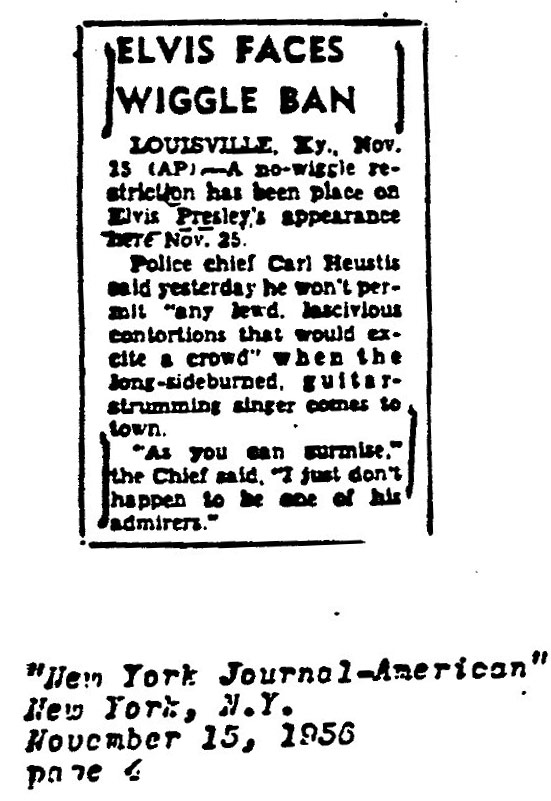

On November 14th, in an attempt at censorship and to thwart potential rioting, the chief announced that he was enforcing a “No Wiggle Ban” for Elvis’ appearance at the show. The report in the papers the next day read, “A no-wiggle restriction has been placed on Elvis Presley’s appearance here Nov. 25. Police chief Carl Heustis said yesterday he won’t permit ‘any lewd, lascivious contortion that would excite a crowd’ when the long-sideburned, guitar-strumming singer comes to town. ‘As you can surmise,’ the Chief said, ‘I just don’t happen to be one of his admirers.'” Ultimately, filmed portions of the matinee show at the armory (reputedly by the police and most likely as evidence in case Elvis violated his restrictions) were taken, unfortunately for posterity, without sound.

The night before the Louisville shows, the boys had performed in Troy, Ohio. According to Lee Cotten’s book, Did Elvis Sing In Your Hometown?, after “driving all night, Elvis arrived in Louisville, Kentucky and booked himself into the Seelbach Hotel. It did not take long before fans began roaming the corridors in search of their idol.” Cotten continued:

At some point during the Louisville trip, Elvis visited with his grandfather, Jesse D. Presley, who lived in a small house in southern Louisville. When Elvis left, he gave his grandfather a new car, a television set, and a $100 bill. By that time, a crowd of 500 had gathered in front of the elder Presley’s home. Later, J.D. and his second wife attended Elvis’ matinee performance. When tickets for this show went on sale, mail orders came in from every county in Kentucky and more than 180 cities.

The show was a sellout with an attendance of 8,500, according to media reports of the time. For additional information on the concerts and reviews in the media following the show, visit the Scotty Moore page.

The Armory’s Modern Life

In August 1960, Seltzer’s lease of the Armory expired and the Armory was taken over by the Jefferson County Recreation Board.

The Kentucky State history opens up the armory’s next chapter:

In 1963, a large-scale renovation of the Armory took place, and the Louisville firm of Wagner & Potts redesigned the interior. The Armory needed to be revamped and modernized because of its age, and to attract more events. The renovation cost $1,950,000, and included the addition of air-conditioning, the conversion of the drill hall into a 5,000 seat arena with a stage at one end, and a considerable change to the front facade of the building. The original arched entry was removed, and a marquee was added on the main floor. The gym that had been located on the 2nd floor was converted into a small arena. All of these changes were made in order to attract new businesses and organizations to Louisville to use the facility and to generate a higher income for the county. In order to facilitate this, the building was renamed the Louisville Convention Center.

According to the Encyclopedia of Louisville:

The renamed convention center assumed a different role in the community by hosting smaller meetings, musical acts, and sports while complementing the larger State fairgrounds and Freedom Hall. The name was changed again in 1975 to avoid confusion with the new Commonwealth Convention Center being constructed a few blocks away. Dubbed Louisville Gardens, the Convention Center Operation Co. chose the name to evoke images of the celebrated Boston Garden and Madison Square Garden. In 1980 the building was added to the National Register of Historic Places and beginning in 1991, was managed by the Kentucky Center for the Arts. In December of 1998, the name was changed to The Gardens of Louisville and underwent a $350,000 renovation.

In 1978, three years before Muhammad Ali’s permanent retirement, Louisville renamed Walnut Street to Muhammad Ali Boulevard. “On February 14, 2003, fighting in her dad’s original home town, Laila Ali TKO’d former world champion Mary Ann Almager of Midland, Texas at 1:55 in the fourth round at Louisville Gardens,” the Women Boxing Archive Network noted.

In August 2007, the Cordish Companies of Baltimore, owners of the 4th Street Live! entertainment complex in Louisville, agreed to take over operation of “The Gardens” from the Metro Louisville Government as part of a $250 million development in downtown Louisville with plans to renovate the Gardens again into a performance and sports venue. That figure had jumped to $442 million in December when more detailed plans were presented to the tax commission for a preliminary vote. Cordish’s plans for the armory fell through in 2012 and the city has been searching for a use and potential developer of the space since.

We’re getting the first glimpses of how those plans could shape up now.

*Special thanks to FECC/TheFunkyAngel for his assistance with this history.