[Editor’s Note: Louisville has made some pretty amazing achievements in its first 238 years—but it’s made a few blunders along the way, too. This week, we’re launching a new contributed mini-series documenting eight of the best and eight of the worst decisions, ideas, or projects that have profoundly affected the city. This list is by no means complete—and you may have strong opinions of your own about what should be on the best or worst lists. Share your thoughts in the comments section below. Or check out the complete Best/Worst list here.]

High-tech research complexes with well-paid engineers and office staff is what all cities seek in business recruitment efforts. Who wouldn’t want such a property-value-enhancing development, especially if it was designed by one of the most famous modern architects of the 20th Century?

Well, not the independent city of Anchorage in eastern Jefferson County in the 1950s.

During the mid-1950s, Reynolds Metal Company sought to build a research office park near Anchorage. The company was founded in Louisville in 1919 as the U.S. Foil Company and had a manufacturing plant in the city. It eventually moved its corporate headquarters to New York City in the ’30s. But in 1958, Reynolds was back with a plan for its research park that would employ 2,000 executives and other white-collar employees.

The problem? Anchorage residents would have none of it. In classic NIMBY fashion, they fought tooth-and-nail against this project, even though it was well-planned by acclaimed architect Eero Saarinen.

While it may seem a little bit strange that we’re listing this loss of a suburban campus just days after lamenting companies building headquarters in the suburbs, hear us out. This loss represents more than just the footprint the campus would have had on the built environment. It’s the loss of what such a headquarters as Reynolds would have made on the entire city.

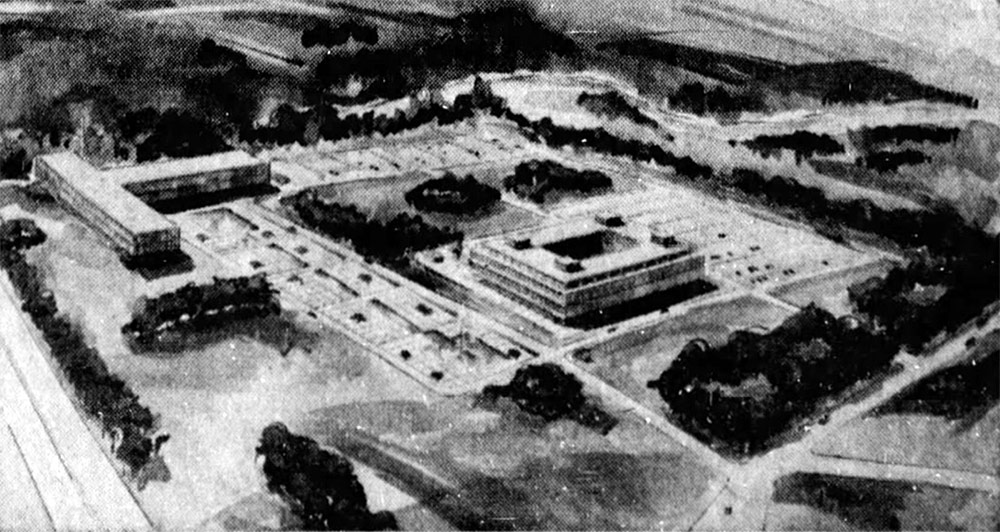

Not to defend the the physical layout and auto-centric nature of such a facility, the historical context in which Saarinen was working saw such a site plan as having more in common with a university campus, arranging a series of low-rise buildings in a completely designed landscape. The architecture would have been beautiful, the urbanism a bad precedent, but the loss of Reynolds is a whole other story.

Saarinen was one of the leading architects of the mid-1900s. A portfolio of his design achievements include the St. Louis Gateway Arch; New York City’s TWA Terminal at JFK Airport; Dulles Airport in Washington, D.C.; IBM Headquarters in Yorktown, NY, on the outskirts of New York City; and Warren Michigan’s General Motors Research Park, just outside Detroit. Nearby Columbus, Indiana, contains several landmark Saarinen buildings: North Christian Church, Irwin Miller House, and the Irwin Bank Headquarters, among others.

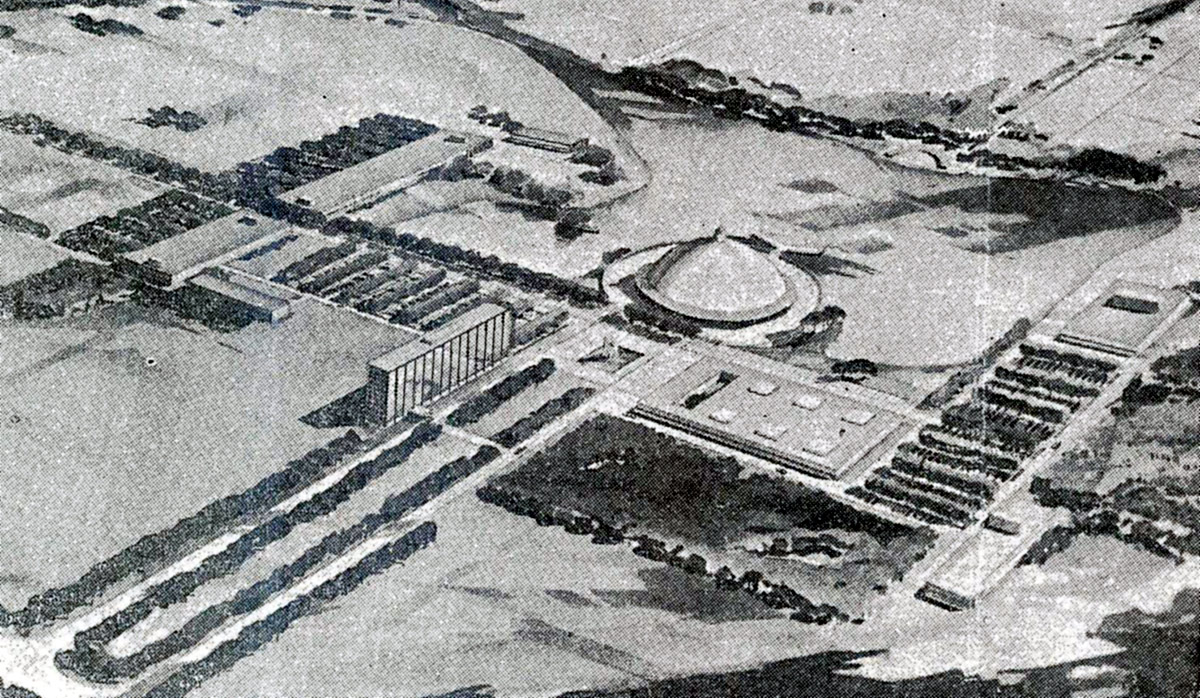

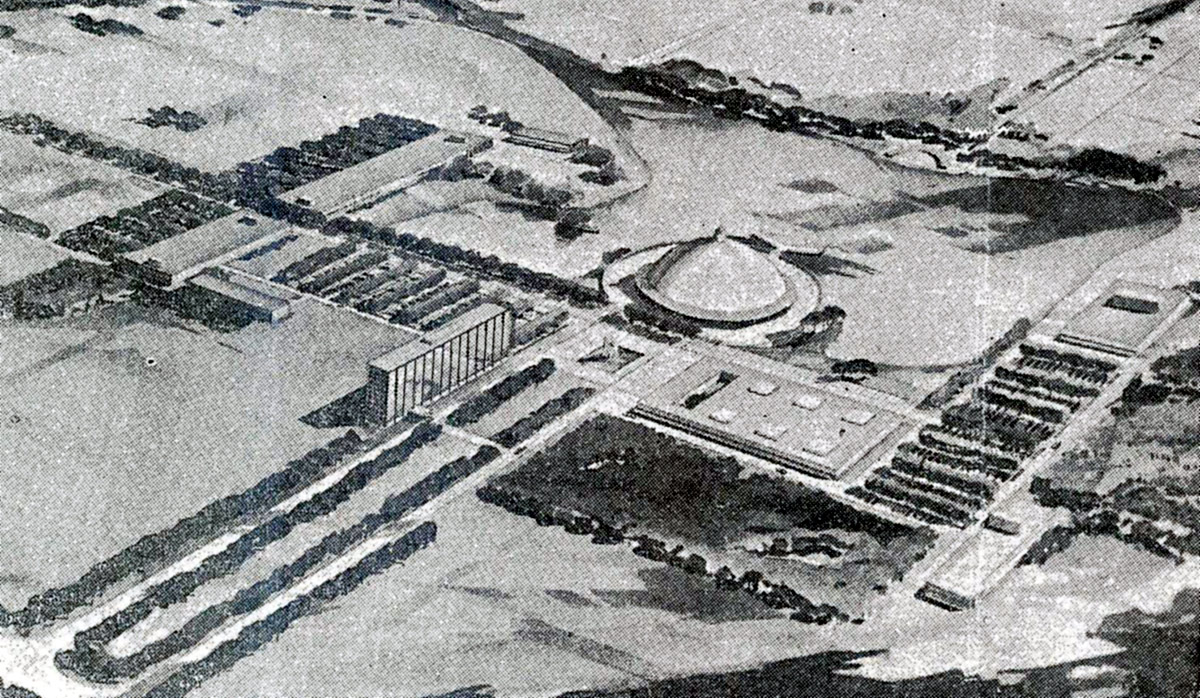

Saarinen designed a sprawling campus the placed Modernist blocks in a rolling landscape off Westport Road near where the old Lakeland Asylum (Central State Hospital) once stood.

The site was formally planned with a wide, tree-lined boulevard flanked by a modern office slab tower and a low-slung research structur. The grand axis terminated on a fountain and domed structure that calls to mind a counterpart at GM’s Michigan Technical Center. Backers described the campus as “parklike.”

What was their hangup? Anchorage residents based their opposition around a rallying cry that the project would usher in suburban sprawl next to their idyllic enclave. They claimed that if Reynolds built its headquarters, more growth and construction would follow on its coattails.

Which, to be fair, is true. But it happened without the project, anyway, and Louisville’s sprawl continues today well beyond Anchorage. But back then, Anchorage was surrounded by farmland, and like anyone who moves to the suburbs to live astride rural landscapes, the impulse to keep everyone else out was strong.

Further, residents did not like that the campus contained a fabricating shop as part of the complex, but Reynolds dropped that component of the layout to try and appease the residents. Opponents cited a concern that Saarinen had not even visited the project site before producing a design.

Ironically, William G. Reynolds, an owner of the company, was an Anchorage resident himself.

Noted Courier-Journal urban-affairs columnist Grady Clay called this planning conflict “one of the most controversial zoning debates” he ever covered. Then Louisville Mayor Andrew Broaddus was quoted saying, “This is a bitter disappointment.”

After the battle in Anchorage, Reynolds purchased another 55-acre site at Newburg Road and the Watterson Expressway for a Saarinen-designed campus, but by then it was too late—the company decided to fold its research operations (and 750 executive and white-collar jobs) into another campus in Virginia. Mayor Broaddus even tried to persuade the company to locate its office building Downtown on the waterfront.

Now, some 60 years later, we’re left with the suburban sprawl surrounding scenic Anchorage, but we’re out a major headquarters and a design by one of the 20th century’s greatest architects.

Whatever happened to the Reynolds Aluminum research center? Shunned from Louisville, Reynolds took its high-paying, tax-producing jobs to a suburb of Richmond, Virginia, where the company’s entire headquarters was located before being purchased by Pittsburgh’s Alcoa.

Reynolds switched architects for its Virginia structure, choosing Gordon Bunshaft of Skidmore, Owings, & Merrill (SOM) instead of Saarinen. That structure is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The company valued architecture in all of its designs, which is evident in its main headquarters and its smaller field offices alike.

“After the battle in Anchorage, Reynolds purchased another 55-acre site at Newburg Road and the Watterson Expressway for a Saarinen-designed campus, but by then it was too late…”

Too late because? Why?

I swear, y’all need an editor, badly.

“…the company decided to fold its research operations (and 750 executive and white-collar jobs) into another campus in Virginia”