[Editor’s Note: Louisville has made some pretty amazing achievements in its first 238 years—but it’s made a few blunders along the way, too. This week, we’re launching a new contributed mini-series documenting eight of the best and eight of the worst decisions, ideas, or projects that have profoundly affected the city. This list is by no means complete—and you may have strong opinions of your own about what should be on the best or worst lists. Share your thoughts in the comments section below. Or check out the complete Best/Worst list here.]

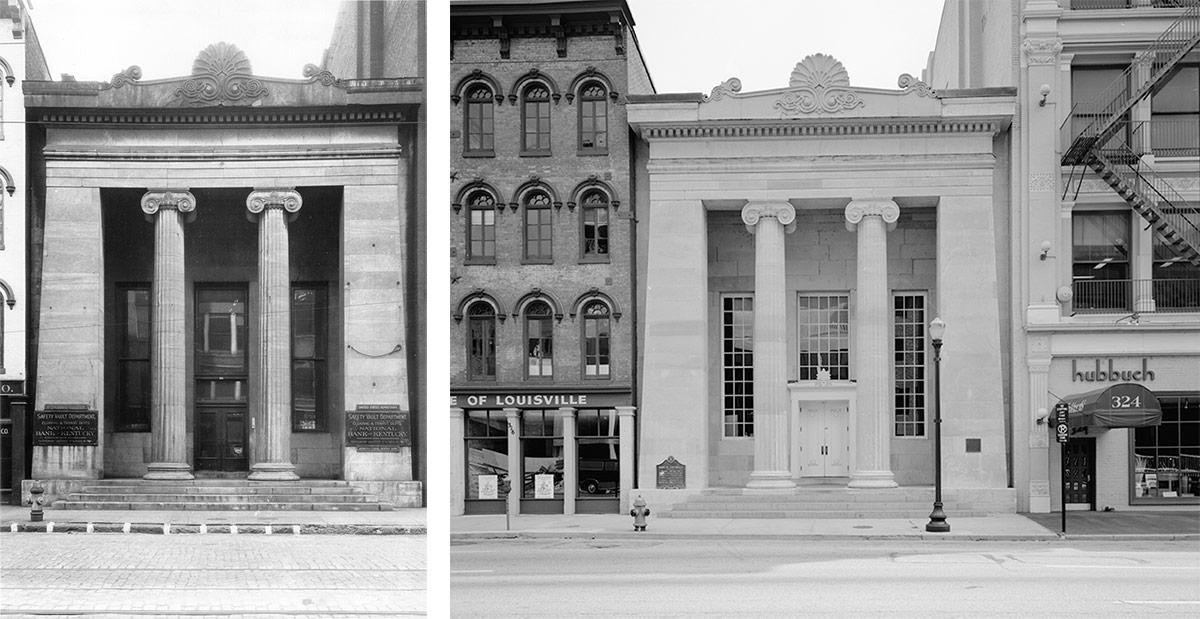

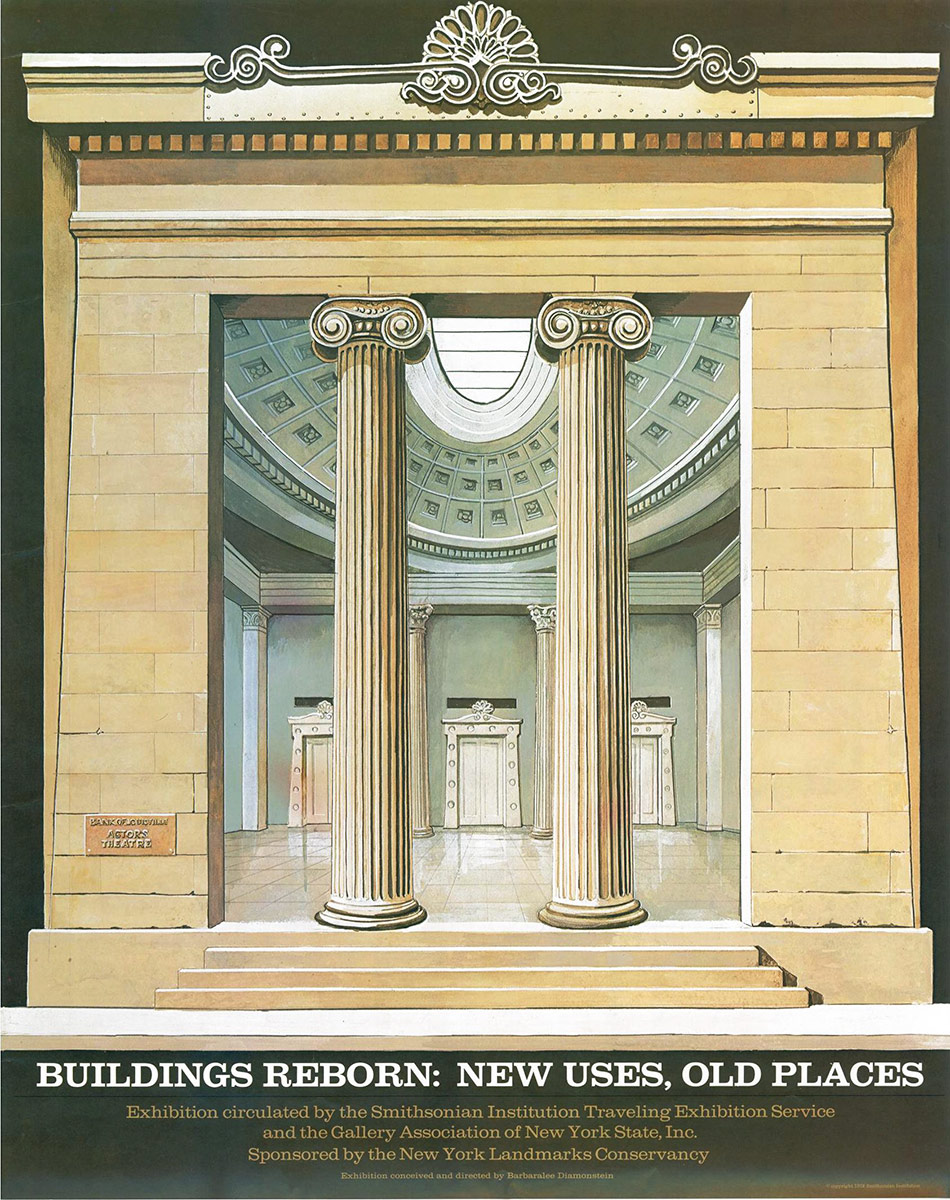

Built as the Bank of Louisville in 1837, this small but distinguished structure on Main Street has survived 180 years of weathering, and, more importantly, “urban renewal” that demolished nearly all of the buildings surrounding it. It was reborn in 1972 as the home of Actors Theater after a major overhaul and expansion by noted Chicago architect Harry Weese.

The building was initially thought to have been designed by famed local architect Gideon Shryock—there even a plaque on the facade that gives him credit. Shryock specialized in this Greek Revival style of architecture and has worked on other noted local buildings such as the city courthouse (begun 1830) and the Old State Capitol in Frankfort (1829).

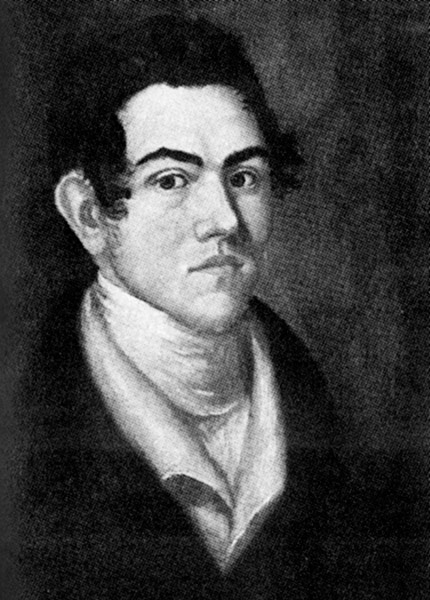

The Bank of Louisville structure was actually designed by James H. Dakin, an architect originally from New York City.

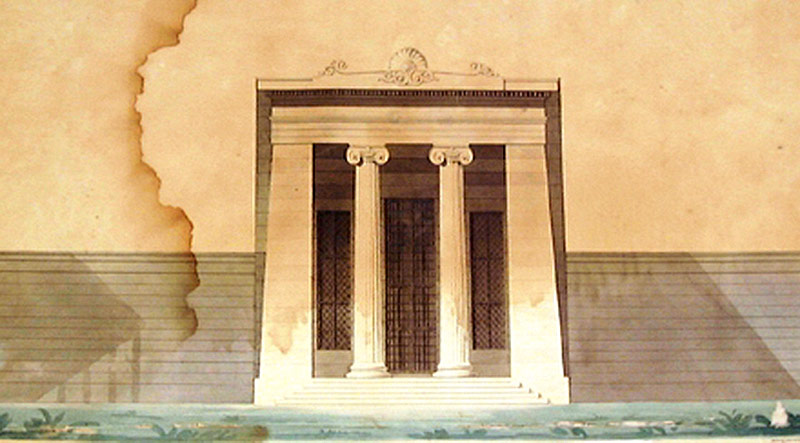

Dakin was relocating to New Orleans, where his brother lived, when he briefly stopped in Louisville and left us with this artistic masterpiece. It is believed that he based his design on a similar bank for the Bank of America (1835) in Manhattan which was designed by an architecture firm where he once worked.

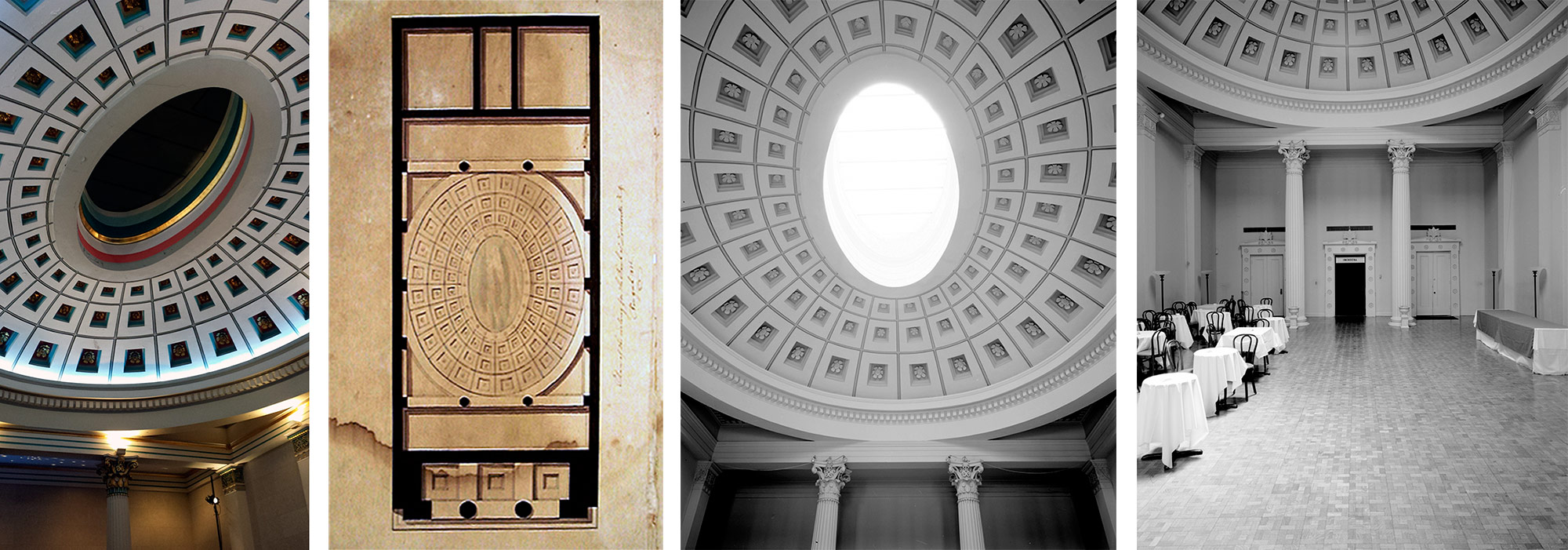

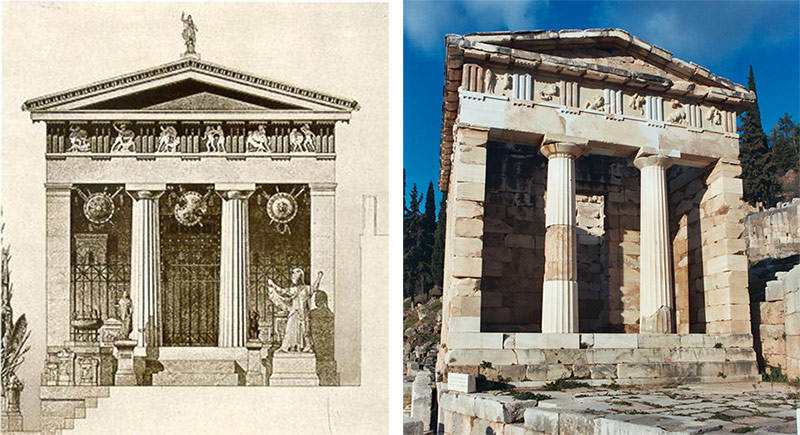

The predecessor to the Bank of Louisville was more Classical in appearance, using flowery Corinthian columns and the structure’s cornice was less prominent than its Louisville counterpart.

For Louisville, Dakin used curling Ionic columns and a large, artistically-inspired pediment. He also tapered the sides of the structure, which draws attention upward to the top center ornamentation and gives the structure a slight Egyptian flare, which was popular in the mid-19th century.

According to documents filed with the National Register of Historic Places:

The Old Bank of Louisville is built on a narrow rectangular downtown city lot flanked on either side by post-Civil War commercial buildings somewhat taller than the bank. The importance of the exterior of the bank is in the dramatic front elevation. It is, in brief, a Greek Revival distyle-in-antis doorway increased to the scale of an entire building. The effect is monumental. The facade is stone. The two fluted columns-in- antis are in the Ionic Order, and the flanking antae are battered, giving the whole building a tremendous visual focus. Above the columns and antae is a simple entablature carrying a superbly scaled cast iron parapet with bold anthemion cresting.

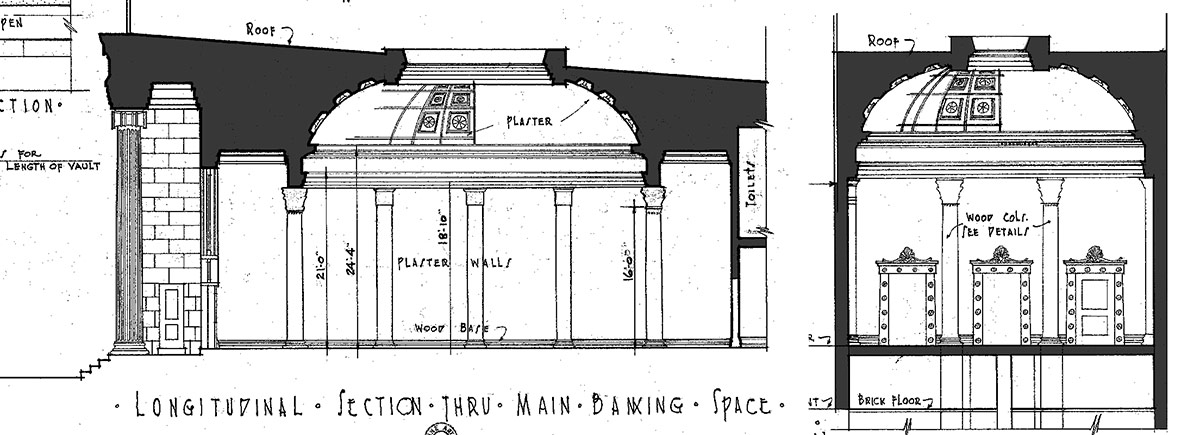

While the exterior is exquisite, the best aesthetic part is on the inside. The Bank of Louisville’s lobby is among the best interior spaces in the city, and could be counted among the best in the state, particularly for its scale.

Michael Graves, the architect of the Humana Building down the street, has said that this was his favorite Louisville structure.

Many, in fact, love the structure, and its doppelganger has appeared in the far-flung suburbs recreated as part of a strip mall. Rather than stone, the modern version is clad with faux stucco over styrofoam.

The building was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1972.

Both bank designs—New York’s Bank of America and Louisville’s own example—were based on another, more famous bank: the ancient Athenian Treasury in Greece. This ancient example established a basic form that has been adapted countless times over the millennia.

Dakin continued on his down-river journey without implementing any other known local buildings. After arriving in Louisiana, he designed a number of notable projects including the New Orleans City Hall, numerous churches, many elegant mansions, and even the state capitol.

Dakin died at age 46 in 1852 from malaria, and is buried at an unknown location. We are glad, though, that he passed through Louisville and gave us this magnificent landmark.