[Editor’s Note: Louisville has made some pretty amazing achievements in its first 238 years—but it’s made a few blunders along the way, too. This week, we’re launching a new contributed mini-series documenting eight of the best and eight of the worst decisions, ideas, or projects that have profoundly affected the city. This list is by no means complete—and you may have strong opinions of your own about what should be on the best or worst lists. Share your thoughts in the comments section below. Or check out the complete Best/Worst list here.]

Churchill Downs is one of the most visible and well-known parts of Louisville’s identity—the racetrack’s iconic Twin Spires of Churchill Downs are recognized around the world. And it’s a thrilling experience to be at the Downs on the first Saturday in May when well over a hundred thousand people stand cheering on the field of twenty in the Run for the Roses.

In short, Churchill Downs and the Twin Spires are intrinsically part of the Louisville fabric. Of what it means to be a Louisvillian, whether you flock to the Downs or stay as far away from the crowds as you can.

For a taste of the Spires’ history, take this excerpt from a 1995 Los Angeles Times article on the centennial of the grandstand’s construction:

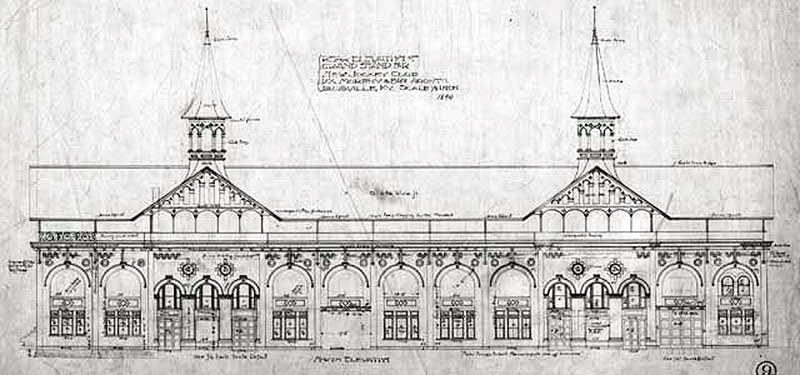

The job [to build the new grandstand] went to D.X. Murphy & Brother Inc., a Louisville firm known today as Luckett & Farley, and a 24-year-old draftsman, Joseph D. Baldez. Like any enterprising architect, Baldez wanted to build something special, something that would take the Downs out of the ordinary. The grandstand was hardly memorable. But Baldez wasn’t through.

He came up with the Spires as an afterthought. placing them as ornamental landmarks to add a touch of panache to the roofline. He designed them with slate roofs and open portals, a dramatic, eye-catching addition to Churchill’s profile…

The 1895 Derby attracted a crowd of just 25,000, many of them probably dazzled by Baldez’s new grandstand and the steeples above it that sat on octagonal-shaped bases with portals and arches decorated by the Fleur de Lis, the symbol of the City of Louisville. From the grandstand’s roof to their pointed tops, the spires measured 55 feet.

While the history and legacy is proudly intact, there’s a fly in an otherwise pristine ointment—modern intrusions that weigh down the original Twin Spires’s design. When you take out-of-town guests to the racetrack, often one of their first reactions is: “Why did they do that?”

That refers to the aesthetically insensitive manner in which a massive construction was added like bookends to either side of the spires, the worst of which was built between 2001 and 2005 at a cost of $127 million. There is no design dialogue between the modern addition and the distinctive icons, the corporate logos of Churchill Downs.

Adding to the sense of aesthetic disarray, light poles were erected in front of the spires, which further distract from these distinguished architectural accents.

And while a packed racetrack full of jubilant and well-dressed patrons is a sight to behold, it leaves us wondering, couldn’t design have made this scene even better?

Many a design-minded local or tourist are dismayed as to why Churchill Downs would have allowed this obstructionist aesthetic to be built around the National Historic Landmark site. An addition of faux stucco and bloated proportions stands out against the simple elegance of the historic grandstand like a sore thumb.

This lack of harmony between the original design and its modern counterpart gives the sense that the extreme make-over of Churchill Downs turned the track into a sort of Las Vegas casino with faux-traditional ornamentation that’s only skin deep.

Much of the modern intervention ignores the rich horse racing heritage that other tracks such as Keeneland have worked hard to maintain and enhance.

This isn’t the first time, though, that a design flaw has posed problems at Churchill Downs.

When the grandstand was originally built in 1875, it was located on the east side of the racetrack.

This meant that spectators had to look westward into the afternoon sun to watch the horseraces, with glare distorting the view—a very distracting orientation to say the least for a sport requiring close observation.

Needless to say, the grandstand was relocated to its present site in 1896 to correct this initial design flaw.

“When a group of entrepreneurial bookmakers took over the struggling track in 1894, the first order of business was to construct a new grandstand,” that LA Times article cited up top reads, “one on the west side of the plant, where the setting sun would not interfere with the comfort of the customers.”

While much of the modern Churchill Downs is cemented in place and its flaws eased with time, it’s hopeful to see the track’s most recent additions take a more sensitive design approach—the facility will continue to grow, after all, as the Kentucky Derby rises in popularity.

In recent years, new configurations to the eastern side of the grandstands and improved design on the track’s high-level interior spaces look much better than than the architecture a decade prior.

But for Louisville’s most recognizable piece of architecture and one of its most cherished landmarks, the Twin Spires deserve the best.

[Top image by Ryan Bjorkquist / Flickr.]

the original steeples should be moved to the opposite side of the track, and recreated in their original design. Just a sense of perspective.

And the very original club house should be build where it originally was… over in the backside.

The lights are the worst. They didn’t even *try* to make them blend in. I’ve seen shopping mall parking lots with more aesthetic lights than the ones at Churchill.

I’ve been saying exactly what this article states since the additions started materializing to their mammoth proportions in relation to the majestic steeples. Such a shame to see the grandeur, beauty, and history

of Churchill Downs minimized in such a way.