[ Editor’s Note: This essay was written on January 23, 2011 by Steve Wiser to document Louisville’s longstanding ambition to propose bold future visions. With the subsequent demise of two of the largest recently-proposed development schemes, Museum Plaza and the Iron Quarter, this essay proves even more relevant today. Published with permission from the author. ]

Towering high-rises clustered to form an overwhelming skyline. Train tunnels under the Ohio River. And a massive state capitol building dominating the city center.

Sound impressive? If constructed, these and other exciting projects would have resulted in a downtown Louisville that today would rival Chicago’s Magnificent Mile. Our city’s history does not lack for large-scale, dynamic proposals that were announced and publicly heralded. It has, however, fallen short in implementing a number of these grand visions.

The Vencor Building is the best known recent unbuilt project. Unveiled in 1997, this 25-story, $60 million curved glass structure by Pei Cobb Freed Architects exhibited a world-class design. But it never went beyond the two-dimensional stage.

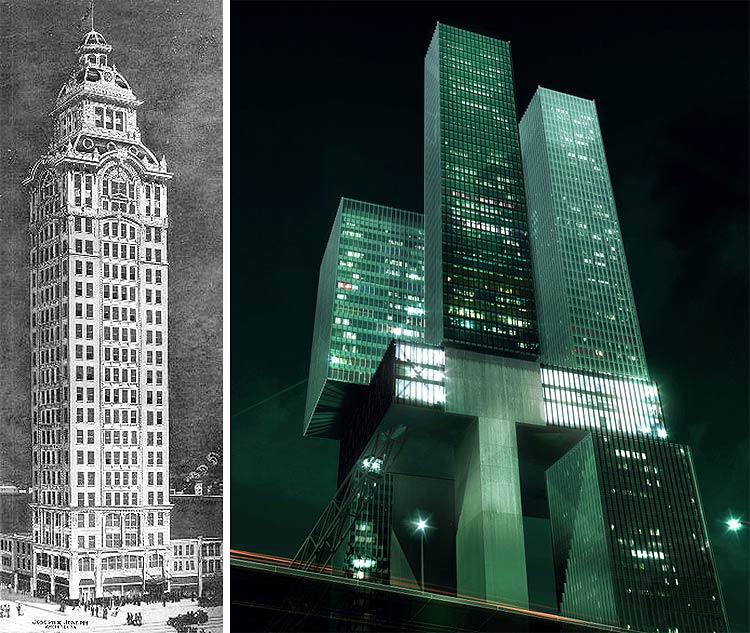

Another spectacular high-rise was the proposed Southern Insurance Building (pictured at top). Conceived by the still-in-business local architectural firm Joseph & Joseph in 1925, this structure had a distinctive domed top and a slender articulated facade. It was planned at Fourth and Market Streets, where 85 years later, at the same intersection, the Aegon Tower would rise in a strikingly similar style. The Aegon Tower, though, was supposed to be the first phase of a two-building complex. Its twin high-rise was never constructed, and a grass courtyard now exists in its imagined place.

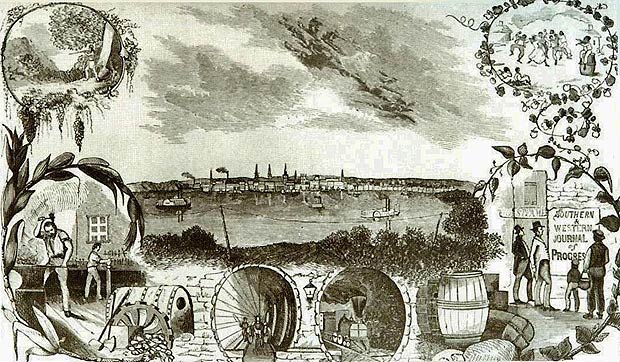

Legendary civic leader James Guthrie championed many of our city’s significant achievements in the mid-1800s: the Portland Canal, the University of Louisville, development of the L & N Railroad, and erection of the first bridge across the Ohio River, to name several. His grandest scheme was an even bigger gamble. Guthrie sought to entice state government to relocate the governor, the General Assembly and other offices from Frankfort to Louisville. He asked Kentucky architect Gideon Shryock to create a signature capitol building in downtown. Shryock had just completed Kentucky’s second state capitol in Frankfort, so Guthrie told him to plan a bigger and better statehouse for downtown at Fifth and Jefferson Streets. Begun in 1836, this mammoth structure took 24 years to build. When it finally opened in 1860, Guthrie’s capital dream was no longer viable, and it became the Jefferson County Courthouse, minus the prominent dome and side porticos in the original drawings.

In 1948, another notable architect, Stratton Hammon, did an assessment of the then 88-year-old courthouse and reported that, “It is quite possible it may collapse at anytime.” A modern government high-rise was designed to take its place. But this proposal never took hold and the courthouse, refurbished and still in use today, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Across Sixth Street, Louisville’s City Hall was also to have been a more imposing structure. Architect John Andrewartha won a competition in 1867 with a design that featured a large central glass atrium and flanking ornate wings. But, when completed in 1873, only the eastern third of the original city hall project was ever built.

Funding difficulties usually are the obstacle that slims down or kills most projects. The Vencor Tower became a casualty when the Louisville-based Vencor Corporation filed for bankruptcy. Another economic victim was the 16-story medical office building (pictured below) that was to be positioned just south of the Heyburn Building near Fourth and Broadway. It was designed by the acclaimed Chicago architectural firm of Holabird and Root and carried a $4 million price tag ($43 million in today’s dollars). Announced in August 1929, just two months prior to the infamous Black Monday stock market crash, it lost out in the economic downturn.

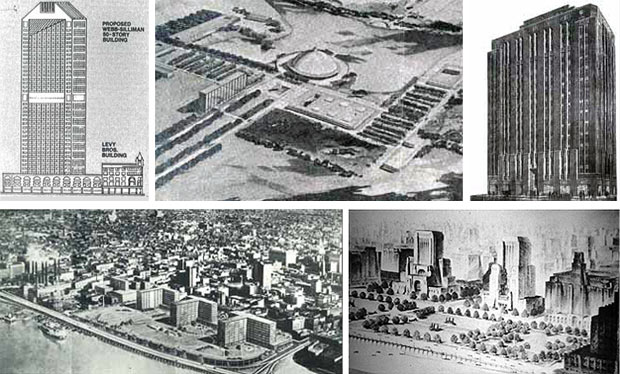

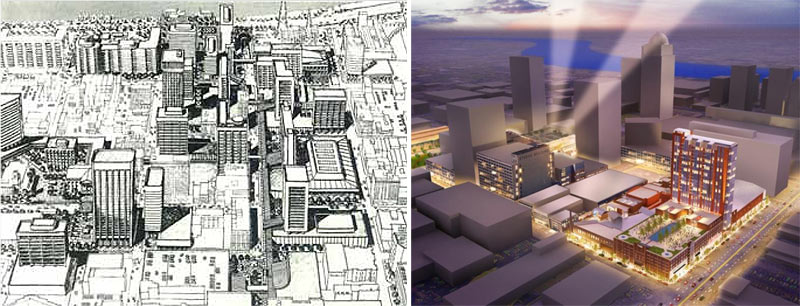

Over the past 30 or so years, a plethora of mega-developments have been announced but never implemented. Here is a highlight list:

- In the mid-1970s, a mixed-use office and residential complex, by local architects Roger Hughes and Dan Church, was proposed at the location where the Kentucky Center for the Arts now stands. Its demise was due to a lack of funding.

- The initial 1978 Galleria plan (in the area now known as Fourth Street Live) contained five box-like towers, of which only two were actually built.

- At the southeast corner of Fifth and Liberty streets, a 30-story, $60-million tower was publicized in 1988. This corner still sits vacant today.

- In the mid-1980s, much fanfare was given to the $100 million Heritage Square complex that was to be located on Fourth Street across from the Convention Center. It contained three high-rises of 14 stories, 22 stories and 30 stories. This site is now the home of the Aegon Tower.

- When the LG&E Tower was announced in 1988, a twin structure was planned just to the east, where a Marriott Courtyard Hotel currently exists. This same location, at the southeast corner of Third and Main streets, was the site for several proposals prior to the LG&E Building. Farm Credit Banks considered a high-rise here, and the Webb-Silliman partnership had plans for a 50-story, $125-million tower in 1985.

- Also in 1985, the Houston-based Continental Group was selected by the city over other development submittals to construct the City Hall North complex at the southwest corner of Sixth and Market streets. It featured two office towers at a cost of $48 million. In 2007, another development group proposed another high-rise project at this still vacant gravel parking lot.

While this is an impressive list of “what if’s,” there are two unbuilt proposals that were an even greater loss for Louisville. In 1908, acclaimed architect Frank Lloyd Wright was considered for a house project on Ransdell Avenue, overlooking Cherokee Park, in the Cherokee Triangle neighborhood and a major project that almost made it was the Reynold’s Metals office-research center in Anchorage. A preliminary rendering was submitted in 1957 by none other than Eero Saarinen. Saarinen was one of the Twentieth Century’s top architects. His designs include the St. Louis Arch, TWA Terminal at Kennedy Airport, Dulles Airport Terminal, and corporate headquarters for John Deere, General Motors, and IBM among many others. Unfortunately, the location could not be rezoned from residential to industrial, and Reynold’s decided to build instead in Richmond, Virginia. This not only was a significant architectural loss, but also a loss for economic development potential as well.

Sometimes, though, projects are built but “downsized,” or altered, from their initial renderings. The Shryock capital-turned-courthouse is an example. At Sixth and Chestnut streets, the South Central Bell Building became another. If you look at its roof, you’ll observe a three-story “penthouse” on top. This utilitarian structure was to have facilitated additional floors that would have made this building a full 20 stories in height. Another example is the downtown Marriott Hotel which was conceptually designed with a creative exterior of masonry and a curvilinear roofline, but the resulting construction left it more generic and boxlike.

More Ohio River bridges have long been discussed and proposed. Most believe they’ll never travel across a new bridge in their life-time, but there have been several whimsical attempts to span the river banks. In 1841, an illustrator drew up a “flying steam duck” that would carry passengers from one side to the other, while in 1861 another graphic depicted a railroad tunnel beneath the river. This was several decades before tunnel ventilation was perfected, and thus if implemented, the passengers would have succumbed to asphyxiation.

Today, our waterfront is becoming a magnificent landscape blessed with some distinctive structures, including the Waterfront Park Place condominium tower on East Witherspoon Street. However, over the past 80 years, there were numerous development attempts to revitalize this riverfront that became part of unbuilt Louisville. There were proposals by St. Louis-based Bartholomew Associates in 1957, Reynolds Aluminum in 1962, and even an effort by a Greek planner named Constantine Doxiadis in 1965. In the early 1970s, a complex that would be home for a fledgling Actors Theatre was considered on the north side of West Main, between Third and Fourth streets.

From Guthrie’s state capital attempt in the 1830s to the Vencor headquarters vision of 1997, there have been numerous unfulfilled dreams and missed opportunities in Louisville. Many of these projects were superb ideas. Some became award-winning designs. But their fates proved a truth that still holds today: With numerous technical and financial challenges to be conquered, there are no guarantees. Only when they become part of “built” Louisville will today’s and tomorrow’s proposals add to the downtown skyline.

Steve Wiser is a Louisville architect and historian who has authored several books including Louisville Sites to See by Design, Louisville Tapestry, Louisville 2035, and Modern Houses of Louisville. His email address is WiserAIA@Hotmail.com and website is www.WiserDesigns.com.

[ Rendering of Bacon & Sons Dry Goods tower at top courtesy University of Louisville Photographic Archives – reference url. ]

Don’t forget the Joe Ley block and Creation Gardens/Service Welding block proposals that show no signs of going forward.

All this is why I have an I’ll-believe-it-when-I-see-it skepticism toward every new development rumor that comes down the pike.

Let’s also not forget another one of Steve Poe’s Grand developments, River Park Park. This mixed-use, multiple highrise and marina project was supposed to be built where River Road and Frankfort Avenue meet. I’m sure funding has stopped this project too, but the website is still up and running. http://www.riverparkplace.net/

The Vencor demise really broke my heart at the time, because to me it (appropriately!) represented a giant “sail boat” rising near the river.

An interesting side note: If you’d ever like to check out what the Vencor Building might have looked like (only taller), head on over to Madrid, where Pei Cobb Freed built a (very, very) similar building as Louisville’s a mere ten years after it was originally proposed. Here are a few links:

http://www.pcf-p.com/a/v/tb/body_0108.html

http://www.pcf-p.com/a/p/0108/2.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Torre_Espacio

Musuem plaza break my heart, louisville cant growth they no money left, louisville has 9 project I think not sure, is cancalled

Other than the Omni project , is there any new building development in the pipeline ?

Museum Plaza was a great loss, and a black eye in the world’s press which had named it one of the new great buildings. Louisville desperately needs something iconic in that riverfront spot. A TV tower like the one in Canada, or a Space Needle would fill the niche with minimal expense, and maximum exposure. The early Southern Insurance building was a loss. Louisville needed such a high rise, especially near the riverfront. Louisville needs a new police headquarters near 9th and Jefferson. And, please, please build something, anything on that long vacant surface lot behind city hall.

Wasn’t there another proposal to build a Hilton hotel on Second Street around 1966? It would have been located around the same block where the Marriott now stands.

I agree with Nick that a multipurpose tower structure would work at the old museum plaza sit..you could still manage to include some of the ideas of museum plaza but in a more slimmed down form…a hotel/loft structure on the ground level with a tower like structure ascending from the top with a mutil-level top house one would house the museum and gallery, the other a revolving restaurant and an observation level