[Editor’s Note: Rollin Stanley is the Planning Director at the Montgomery County, Maryland Planning Department. I first met him nearly a decade ago shortly after he was named Executive Director of the St. Louis Planning and Urban Design Agency while I was in college. He understands how cities work implicitly and is an outspoken advocate of good urban design and transit-oriented development. Stanley writes the Director’s Blog at Montgomery Planning on which this post was originally published.]

For Thanksgiving in 2011, my wife and I drove 900 miles to visit friends and family in St. Louis, Missouri. We drove an extra 50 miles to go the southern route via I-64 past Charleston, West Virginia and Lexington, Kentucky, before stopping over in Louisville for the evening. Despite the rain, it was a great opportunity to visit the city for the first time.

The cities of the Midwest are poised for resurgence. Filled with creative, energetic people and with a low cost of living, a new generation of artists, entrepreneurs and immigrants are seeking to establish themselves. In fact, recent surveys show cities like St. Louis are experiencing a more than 80 percent increase in young residents.

Initial impressions

First impressions are always important when you are pulling into a strange city after dark and in the rain. Louisville is no exception. The Google directions bringing us along the rain soaked I-64 along the Ohio River to our exit on South 9th Street didn’t show off the city’s best side. To a person unfamiliar with center core cities in the U.S., it could feel a bit like Chevy Chase traveling across America in the “Family Truckster” and reinforce the stereotypes held by many people about inner-city America.

This clip from the movie, Vacation, is funny, yet reflects the image of inner cities that many people have. The entry points to our cities are critical to bringing people to the inner core.

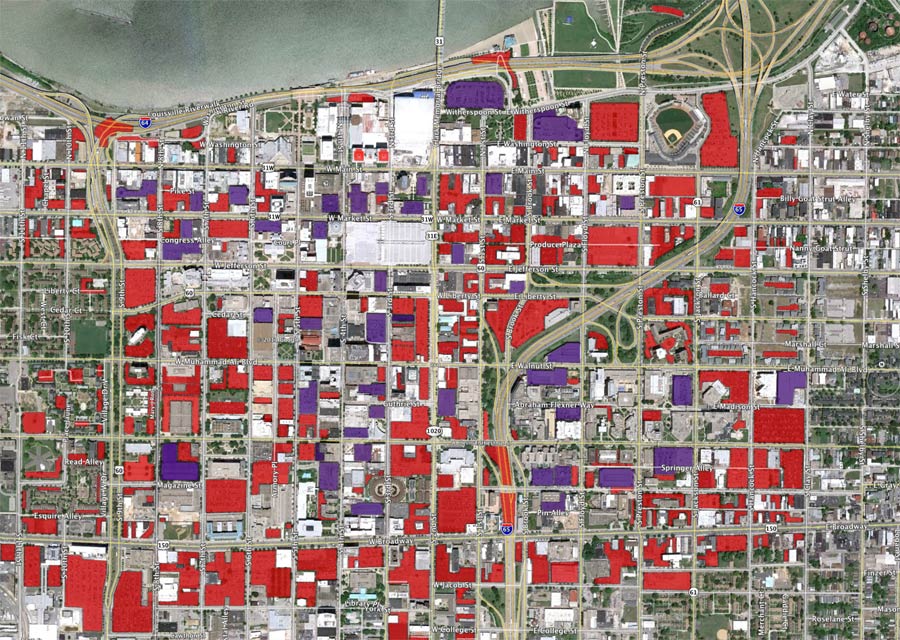

The great scourge of industrial cities is the race to create as much parking as possible. Some civic leaders see demolition and paving as a sign of progress and Louisville along with Kansas City, is a prime example. William Whyte in his book City: Rediscovering the Center, says “If you tear down enough of your downtown for parking, pretty soon there won’t be any reason to go there and park.”

Sure enough, downtown Louisville has plenty of examples intended to prove this proverb. They have the waterfront development and “Fourth Street Live,” the Cordish downtown entertainment district similar to Kansas City. These developments are intended to draw people back downtown, the place they left kind of because, well, lots of stuff was torn down for parking lots.

And guess what? Nobody parks on those surface parking lots because they are too far away from Fourth Street Live for anyone to park there. And if someone did, they would not feel safe walking across all the vacant lots to get to the entertainment center.

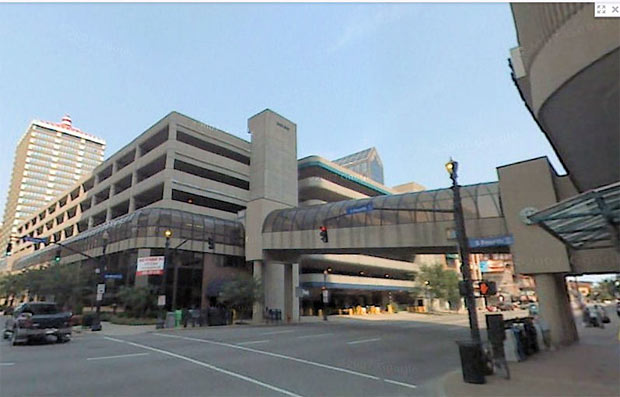

Fourth Street Live mirrors similar downtown developments by the Baltimore-based developer Cordish. While it has many of the chains we are familiar with around the country, there are standouts like the Maker’s Mark Bourbon House and places with great names like “Howl at the Moon.” However, this two-block stretch of South 4th Street is disconnected from the river by several government buildings and the too often repeated downtown convention center.

The Louisville parking landscaping really hampers the potential to create depth to the downtown. As you move south away from the river along 4th Avenue, going over one or two blocks to the east or west you arrive at a sea of surface parking. Those parking lots spawn the decline of adjacent properties, the very places the surface parking was intended to help. The lots are vacant at night, so the places next to them begin to decline.

This is a great video from Rochester in 1964 touting the virtues of the city based upon the ease of parking. Wow, just makes you want to jump in and drive to Rochester.

Challenges

Louisville is clearly a place of contrast, just like so many other cities in the Midwest. Pockets of success separated by surface parking lots and questionable decisions about frontages, highlight some of the toughest challenges with the core of the city. The challenge of creating “depth” to the success, linking the positive nodes, is so difficult when growth is first limited, then competing with the unlimited sprawl of the burbs.

Louisville has some tremendous assets. But it has lost tremendous assets as well.

1. Louisville torn down a lot of stuff.

Downtown Louisville is an old architect’s dream, what remains is shaped like a T square. There are lots of buildings that parallel the waterfront, some good and some bad, and then there is the South 4th Street corridor stretching at right angles back from the river, forming the spine of activity, the “straight edge” of the T square. I love South 4th Street, but only the area south of the convention center.

So many cities tried to revitalize their downtowns by bringing in convention centers. While convention centers bring people into hotels and to patronize local business, almost all create sterile street frontages that mimic big box stores.

Government buildings are also a challenge, creating long expanses of inactivity that work against creating a vibrant neighborhood. They are like parks after dark. Nobody wants to walk past them. I learned a great lesson from an urban pioneer by the name of Joe Edwards in St. Louis. He singlehandedly revitalized the “loop” neighborhood, including bringing trolley lines back to the commercial district.

As Joe rehabbed commercial buildings, he would work to lease space to a variety of retailers. Too many restaurants would mean little happening during the day. Too many shops would leave the street vacant past after 9 p.m. So he would mix the uses, creating variety along the street. Both the convention centers and government buildings work against this principle.

2. Historic assets

Much of downtown Louisville is gone forever. There are pockets of underutilized historic resources where only the ground floor is being used. This is a real shame. These small pockets offer the potential for affordable redevelopment through the use of historic tax credits and other financing tools. With all the creative forces in the city, one has to believe there is a solid constituency for these spaces with rents being offset through the tax credit restoration.

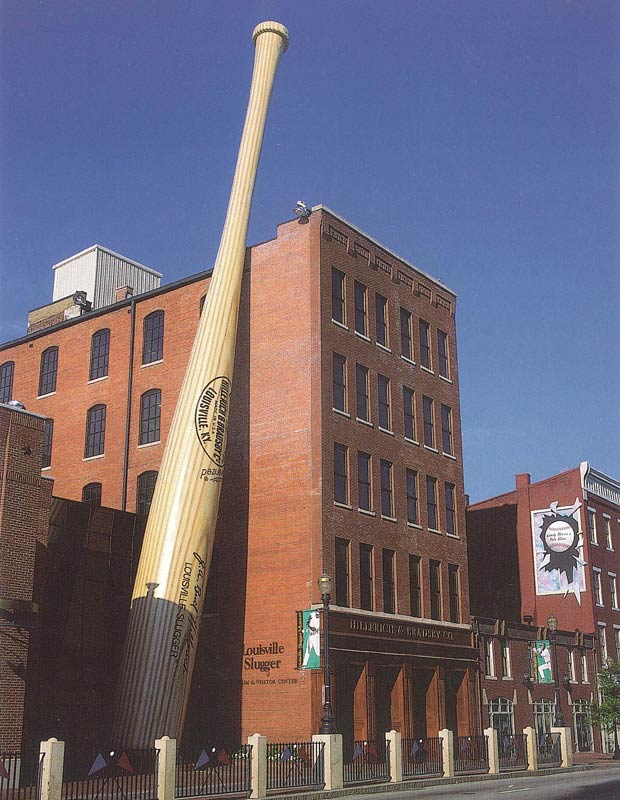

The Louisville slugger museum would not be the same if that big bat was leaning against some run-of-the-mill, recently constructed building? Could the small strip of historic buildings nearby has the bones for a terrific neighborhood, where people walk dogs, eat breakfast at the local eatery on Saturday morning, alongside tourists visiting the Slugger Museum or the Muhammad Ali Center just to the north along the river.

Louisville is not alone. In Atlanta, where I did some consulting work about eight years ago, I was shocked that city officials were not using historic tax credits to help revitalize. In St. Louis, we created over 4,000 new units of loft housing in the core of downtown historic tax credits and the like. Building the local capacity in the developer, legal and government sectors to make these things happen is critical.

3. One-Way Streets

Other than saying they serve horse meat, nothing kills a restaurant faster than locating on a one-way street. One-way streets serve one purpose and one purpose only: getting people in and out of the core area as fast as possible. A driver needs to travel 25 mph or less to make eye contact with a pedestrian. So if you are trying to create vibrant pedestrian streets, how does a one way street that pushes cars through as fast as possible work toward that goal?

There are few places on the planet where retail succeeds on a one-way street. And these places have density, something Louisville does not have. Is there really a need for four lane roads running one way in front of the Louisville Slugger Museum?

Show me a city without congestion and I bet it is not a place where people go and members of Gen X and Y live. We want people to slow down, look out the window at the retail environment and have street parking to liven up the sidewalk.

Bright spots

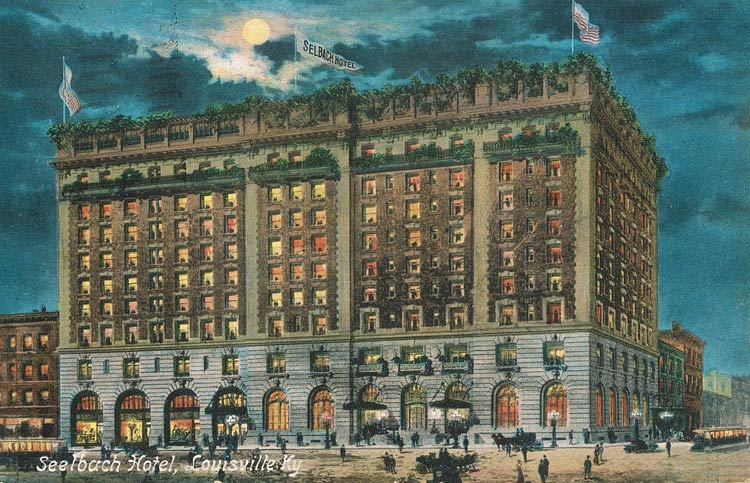

In Louisville, I saw pockets of amazing creativity and resiliency. Take the grand old hotels. Louisville has some great ones like the Seelbach (we stayed here) and the Brown. I understand the wedding sequence from the Great Gatsby is modeled after the former. It has a great long wood bar with some real tradition.

And to contrast these great old hotels, there is the fabulous Museum Hotel over by the Slugger Museum. The restaurant/hotel is themed as an art museum and is one of the coolest concepts in North America. A terrific example of the creative energy in this city and the Midwest. Fun, unusual and full of energy, these are the spots that are the nucleus for change. This hotel and museum is the focal point to transform this neighborhood.

The scale of the streets is another asset. Most are narrow, and where the buildings remain, framed right up to the sidewalk, giving a real urban feel. There are good examples of architecture from many eras and this is really noticeable when you stand along the waterfront and look back towards the downtown. And where the city has invested in those streets, they have created some great urban furniture and property owners created some great small urban spaces.

Walking through any city, it is fun to look to discover hidden spaces that really open the potential of a commercial district, creating the intimate spaces that attract people to an area. With sidewalks, these are really the “public spaces” in an urban area that are most frequented.

Downtown Louisville is a case study on urban America. It can become one of the cooler places in the Midwest. It has a lot of assets: the obvious creative spirit of so many residents, the great bourbon selections in so many establishments. But it will require baby steps, moving forward one small area at a time. Ignore the quick fix ideas that require more buildings to come down, closing a street, or sterilizing the street activity through long blank walls. If a bank or pharmacy wants in, make them open up the facades, no walls that don’t have doors every 50 or 60 feet.

Explore the myriad of incentives that make downtown projects economically viable and attractive to everyone. Work with property owners and find new ones who have the energy and vision to make these projects work.

And, please, get rid of the one-way streets.

Wonderful article!

He is spot on about our parking lot situation. Turn those lots into a Wal-Mart for all I care. Our planning commission needs their heads examined.

the buzz about louisville is contagious, we’re upriver from louisville in cincinnati & had the opportunity to work on one of their landmarks, the zorn water tower & pump station. Cities like louisville that have a creative vibe serve as business incubators due to lower costs of living.

Great article. I agree with the parking lot assessment and the one-way streets – I hate them! Oh, and bury the power lines.

Need more new skyscraper tower make big city

You talk pretty, Taz.

I hate that the old Schuhmann’s Click Clinic neon sign was changed to advertise a strip joint.

I sent a lot of film through Schuhmann’s. I miss the people that worked there.

Wasn’t the Ohio an ice cream shop about 20 years ago?

Ice cream, cell phones, a lot of businesses come and go at the old Ohio. When Peter Bodnar painted the mural 20+ years ago he put D.W. Griffith inteh ticket window.

Has anyone heard about the reconstruction of the Neumarkt district in Dresden, Germany (link below, pictures at the bottom of the page)? Ever since I learned about it, I can’t help but be curios about what the effect would be if a similar program was implemented to fill in some of those giant surface level parking lots. Thoughts?

http://www.oldlouisville.com/ruins/2ndPresb/2ndPresbyruins.htm

I designed & painted the mural on both sides of what is left of the Ohio theater in the 1992. D.W. Griffith is the ticket taker on the other side.

Nice work, Mr. Bodnar. That Ohio Theatre ticket window is a truly fun artifact.

Sorry, but you can’t really make an analysis of the parking situation on a rainy weekend when there is no one there. If you come downtown on a normal weekday (which I do everyday where I work at 7th and Market) you will find that all of those parking garages are full. They are necessary for the many large offices that operate there. Lots of people go downtown and park everyday, to work!

@Ted – Nobody disputes that parking is necessary. It’s just a question of how it can best be fit into a vibrant downtown. Look at a big city downtown like Washington DC or Manhattan. Virtually no surface parking lots anywhere, and very few single-use garages. Most garages are either under buildings or above street-level retail. That’s driven by how dear real estate is in those places, but it also helps to preserve and reinforce a vibrant streetscape.

There’s no reason we couldn’t redevelop existing parking space in ways that would be more friendly to a vibrant downtown.