These days, terms like “shrinking cities” feel a lot like the “slum clearance” and “urban renewal” of the last century that wiped out large swaths of our cities in dramatic fashion. Rarely do we encounter demolition on a large scale any more. But when it arises, no matter the cause, it should give any urbanist pause to hear that 128 houses in the already demolition-ravaged California neighborhood are planned to be removed and the land permanently kept from development in the heart of the city.

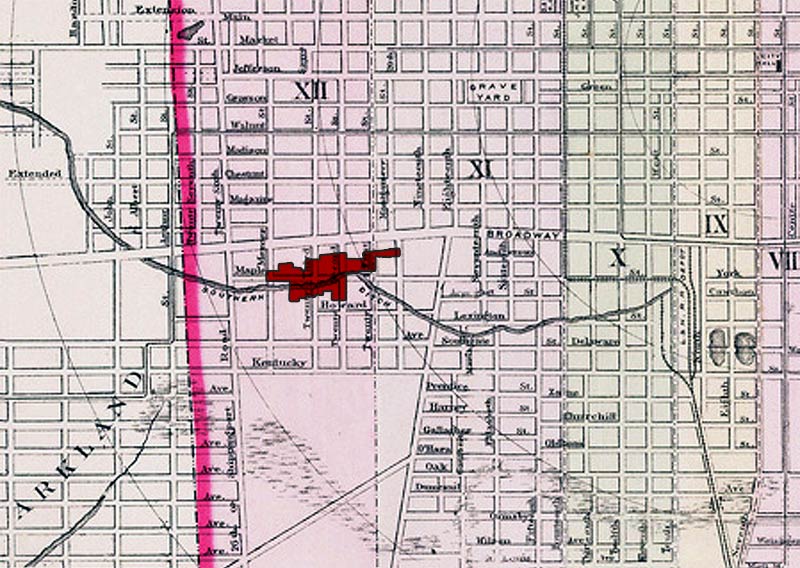

That’s the latest plan from the Metropolitan Sewer District, which was awarded $9.75 million in grant funding to acquire and clear 15 acres along Maple Street between 21st and 26th streets known for flooding in heavy rain events. But while the project has been widely reported in local news, some important details have been left out or are still missing.

Neighborhood Context

When a solid block of 15 acres is proposed for removal, it’s important to understand what we’re losing. This area around Maple Street was originally built with small- to medium-sized single-family housing on the city’s fringe beginning in the late 19th century, moving slowly east to west into the early 20th century. Industry also grew up in the area and expanded during the 20th century. The existing building stock offers a few surprises.

The dominant housing type in the target area is the wooden shotgun house, but bungalows and two-story houses can also be found across the neighborhood as well. Houses were typically built on the same plane as the sidewalk, not elevated on a small grassy berm as was common practice in other Louisville neighborhoods, a detail that no doubt exacerbates flooding concerns. A few brick houses can also be found, but one stretch of four brick houses pictured below on 24th Street sits boarded up.

A surprisingly large number of houses in the target area aren’t historic, but were built quite recently. While the new houses conform to the urban pattern of the neighborhood, it’s easy to pick out the newcomers by their lack of historic style and proportion.

From a walk around the neighborhood on Google Street View, it looks like most houses are occupied and there are generally few missing teeth, except a few key large lots used for industry or for storing various materials as the neighborhood erodes on its edges.

Real Flooding Concerns

It’s also important to clearly understand the legitimate flooding problem MSD is addressing. The last dramatic flooding event happened in 2009 when a massive rainstorm dropped 8.5 inches of water per hour, inundating the city’s sewers and turning Maple Street into a river. While such a rain event is certainly one of the most severe the city has seen in recent years, the flooding problems here are made worse by impervious paved and built-up areas surrounding Maple Street. To the east, large warehouses surrounded by parking lots send rain water rushing into the sewers faster than can be handled while along Broadway, more large parking lots serving the suburban-style development that was foolishly allowed to be built adds to the excess water.

The bigger problem is that flooding isn’t just clear rainwater. A large combined sewer runs underneath Maple Street, and when the rain overwhelms capacity, a murky flood of sewage can fill the streets in what’s referred to as a combined sewer overflow (CSO).

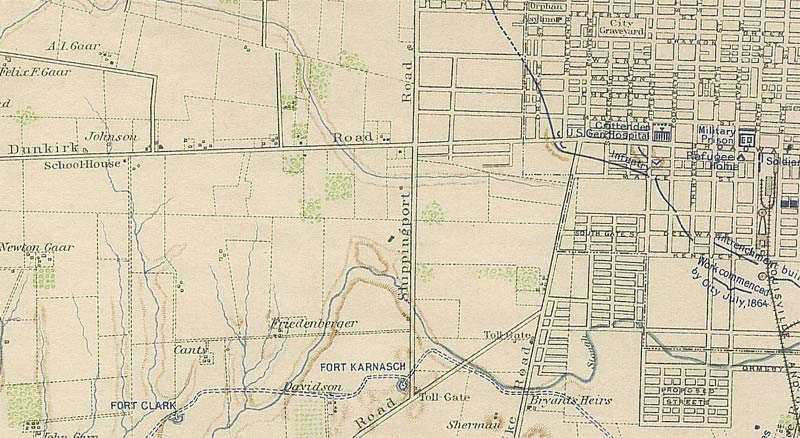

A Lost Watershed

It’s also interesting to look back further into the history of the Maple Street area. Not to the late 19th century when subdivision and development began, but decades before when West Broadway was known as Dunkirk Road, Dixie Highway was the tolled Salt River Turnpike Road and 26th Street was Shippingport Road. Back then, from the 1870s or earlier, this area and much of the interior of West Louisville was still sparsely-populated farmland, laced with streams and dotted with ponds and wetlands.

Clearly visible on old city maps is the beginning of the Upper Paddy’s Run watershed, also referred to as the Southern Ditch, that ran along Maple Street directly through the center of the target area. As was often the case in our environmentally-unaware past, the watershed was filled in or otherwise covered over, removing the natural systems that helped to store water during storms.

Looking Ahead

Back to the present day, MSD plans to acquire the 128 houses highlighted above over the next 18 to 24 months and will begin transforming the target area into a flood-retention zone. With the nearly $11 million in funds (MSD will chip in a 13 percent grant match, or about $1.27 million), that means about $86,000 on average per house. Property owners will be offered a pre-damage fair market value for the houses and renters are eligible for up to $5,250 in relocation funds.

MSD expects everyone in the target area will opt to take the buyout. “The program is optional, but the values offered are pre-damage. The interest shown thus far has been very high and we anticipate working closely with the property owners so that no isolated homes remain,” said Justin Gray, Senior Technical Service Engineer at MSD. Property owners and residents will be notified over the next several weeks with more information on the program.

Houses will then be removed and the area will be remade with green stormwater infrastructure, flood storage space, and park land. MSD has already been reaching out with industrial neighbors like Brown Forman to coordinate these efforts. The spirits company directly east on Dixie Highway has already begun implementing their own green stormwater management systems.

Some of the green infrastructure systems that MSD is exploring include pervious paving, rain gardens and bio-swales, infiltration drains, and water-capturing cisterns. The general idea behind the techniques is to eliminate or slow rain water from entering the city’s sewer systems to the combined sewers don’t overflow and cause flooding. You can read more about MSD’s green stormwater infrastructure systems here and here (Warning: Both PDFs).

Lingering Concerns

So what we have learned so far sounds pretty good for everyone involved: Residents in a flood-prone area will be offered a chance to escape the waters and receive fair market value for their homes, West Louisville gets a 15-acre green stormwater infrastructure project, and the California neighborhood gets a little more park space.

The big downside so far is that the city is losing nearly 100 historic houses, many of them endangered shotgun houses. Community leader Haven Harrington III raised concern about the plans recently, asking if there were other options to invest $11 million in the neighborhood and achieve the same flood mitigation outcomes:

The question that I have that nobody has raised is simple, do we need to tear down 128 homes to fix a flooding problem that was caused by a once in 100 year rain event? Could the $9 million in grant be used instead to improve the neighborhood and may be fix the flooding problem in other ways? From the way the article reads it sounds like the real objective is to tear down a large part of the California neighborhood so MSD can build an underground storage basin. As of now MSD doesn’t know what they will do with the soon to be 15 acres of green space. Why tear down a large part of the California neighborhood if you don’t know what you’re going to do with it? Are there other ways to fix the “flooding” problems?

This uncertainty of what future plans will look like is certainly alarming, especially since it’s going to leave a lasting and permanent mark on Louisville’s urban landscape. Once the houses are removed, MSD will restrict the deeds in the target area to prohibit all future structural development. A clearer vision of how remaking 15 acres in the California neighborhood could improve the area, even beyond the flooding problem, would go a long way toward allaying these concerns.

While MSD’s goals are clear, create new stormwater infrastructure to limit flooding and possible add park space, what the end result will look like hasn’t been determined. “Right now, we do not have a concept developed as we wanted to confirm that the grant funding would be received before devoting any further resources to the idea.” said Gray. “We will certainly coordinate with Metro Parks and surrounding neighbors as we move forward. A landscape architecture firm or engineering firm will likely assist in developing the concept.” (Still, Gray described plans for a park with uncertain terms like “If we do develop a park once the acquisition is complete…”)

What must be avoided is the removal of 128 houses and a generic water-retention basin built creating a barrier in the neighborhood if funds can’t be found for more ambitious green infrastructure. “As of now, we only have funding to acquire the homes,” Gray said. “Any further action will have to be authorized by the MSD Executive Director and Board.”

Potential

Once these 15 acres are gone (and if the Y foolishly destroys one of the areas most iconic buildings), California will have seen 50 contiguous acres cleared in the past few years, all within one to two miles of the center of downtown. If the houses in the MSD target area are to go, it should be seen as an opportunity to improve West Louisville well beyond mitigating flooding. There’s clearly room for plenty of study here, but here are a few ideas that can get things started off:

The impacts on walkability need to be studied to keep the rest of the neighborhood connected to Broadway and the rest of the city. How can we selectively implement stormwater infrastructure while also healing the rough edges that come with such demolition programs? More ambitiously, could the area benefit from restoring some sort of natural or manmade watershed along the lines of the original creek? Can green infrastructure and parkland be implemented in a coordinated way that allows some of the land to be remade on higher ground and rebuilt to increase the walkability, density, and sustainability of the neighborhood? There’s huge potential in these 15 acres that could uplift the community while limiting flooding events.

I helped clean out a home on Maple Street just after the August 4th rain storm. The Owner stated that is was the third time it had flooded since she’d moved in. The previous two times there had been less than a foot of water on the ground floor of the home. On August 4th, there had been about 3-1/2 to 4 feet of water in the home. The smell of the sewage in the air that day was gag inducing. The despair on her face told quite a story.

I hate to see the urban core loose space that can be used for residential and I hate to see some of the 100 year old homes go, but the fact remains that the area was a water catch for hundreds of years before Louisvillians came along and built houses. It was human intervention that has caused the issue.

We now have an opportunity to not only build a flood control basin, but reclaim the area as green space for future generations. The worst thing that could happen (and we should remain mindful of) is that this could just look like an east end development retention basin with tall grass, cat tails, standing water and a bad mosquito problem. Careful design must go into the project.

The reclamation of the area, under a sound plan, will be a good thing. But only time, political will and budgets will tell.

In response to an at-risk flood area on the Northside, the City of Minneapolis has reconstructed a street as a type they call a ‘greenway’ – instead of a roadway, they built a paved trail and sidewalks with rain gardens interspersed along with underground cisterns. This situation may differ in severity of flood events and also in physical structure, but is a possible alternative to widespread demolition. Typically restricting cars from a street is a no-go in North America, but may be preferable to removing all the houses.

Here is a link to the City’s project page:

http://www.minneapolismn.gov/cip/all/cip_flood5_index

Maybe they should try giving the houses away to anyone who could pay to have them moved. At the very least let someone like Joe Ley come in and salvage out the materials and etc out of the houses. Its a shame that here in louisville we still think nothing of tearing down old houses instead of trying some sort of alternate solution first.

The shrinking cities is not a recapitulation of slum clearance. The latter was in the name of expansion and private development – the latter is predictive only of uncertainty and a recognition that growth or population increase is not the only attribute of a great city. Your broad claim not only hinders creative approaches to managing decline, it also reinforces growth at all costs. Shrinking cities approaches are in their infancy and could actually provide new industries, land uses, and forms of governance. Your readers would be wis to think a little deeper about urban transition.

The reason these lands are being purchased and why many of these houses are “new” is these are Severe Repetitive Losses through the NFIP program (google it) … these homeowners pocket huge amounts of cash each time it rains. They lose their house, build it again, lose their house, build it again; it’s easily the easiest way to pocket thousands of dollars on the government dime. Glad to see this program is finally taking homes off the market.

I haven’t driven that area for several months, so my recall is a bit dated. However, are most of those 128 homes “worth” saving? Would their physical condition merit them being moved to other lots or locations in Louisville? I am sure a homeowner and their own family would appreciate keeping their home, maybe even if it meant keeping it in another area. There seem to be plenty of empty or overgrown lots around town aching to have some life put into them.

If enough of the housing stock is still in good shape, why not close Maple and recreate the creek?

I fear our city’s commitment to creating new affordable housing are eclipsed by the scale of this action. I’m surprised Fischer didn’t just have the neighborhood carpet-bombed during Thunder over Louisville.

Seems that the real historic part of California is the part btw 18th Street and the railroad, south of Broadway. It appears to have been platted before the Civil War based on that fortifications map,and was already built on by the 1880s (acording to that old insurance map thats online at UofL). So you probably have some early building stock in that part of California.

But, yeah, great commentary on Louisvilles lost landscape. Another area that was built on old watercourses was “Black Parkland”, west of the main Parkland plat.

And alternate plans abound! All that grant money sure would buy a lot of pervious pavement. Why not rip up the asphalt, and install all pervious pavement, throughout the area???@Thomas –

@Thomas – Genius, Thomas!!!