In 1958, famed urbanist Jane Jacobs penned an important piece for Fortune magazine called “Downtown is for People.” Published three years before her pivotal book Death and Life of Great American Cities, the essay took on an epidemic of mega-projects that aimed to remake cities’ urban cores with large-scale development, often ignoring or tearing out anything that stood in their way.

“This year is going to be a critical one for the future of the city,” Jacobs said in her essay. “All over the country civic leaders and planners are preparing a series of redevelopment projects that will set the character of the center of our cities for generations to come. Great tracts, many blocks wide, are being razed; only a few cities have their new downtown projects already under construction; but almost every big city is getting ready to build, and the plans will soon be set.”

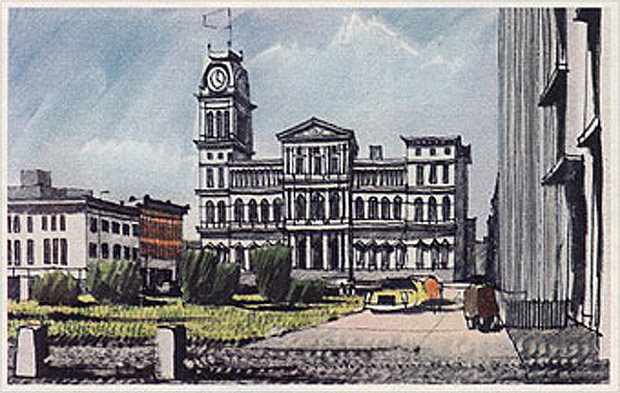

Louisville has had its fair share of mega-projects that ripped away swaths of historic fabric. Think about the Kentucky International Convention Center (KICC), the Galt House complex, or the twin towers surrounding what was once the Galleria, now 4th Street Live! It’s been decades since the scars those projects inflicted on the city’s urban fabric have largely healed or been forgotten, and few remember what once stood in their places.

Jacobs was right in her prediction of a changing cityscape. Louisville was among countless cities which dreamed of vast redevelopment schemes in the middle of their historic downtowns. Louisville’s core is replete with entire-block or multi-block developments, that while sometimes adding a dramatic building to the skyline, contribute little to the activity and life of the street. The KICC presents a mostly dead street wall for two blocks and does little for the average Louisvillian who is not attending a convention. Across the street, a full block Marriott and another full-block Hyatt hotel present deadening walls on most of their street frontages, despite offering a small amount of retail around the hotel entrances. And while a dramatic skyline looks nice on postcards, it’s the street level that matters to the life and vibrancy of a city and its residents.

For every mega-project that was built in Louisville, there was another that went unbuilt. A variety of schemes to remake the waterfront came and went through the years and once Louisville’s leaders considered tearing down City Hall and Metro Hall for what would have been a mid-century cluster in the Civic Center. We can all breath a little easier that those heavy-handed proposals are history.

Jacobs predicted presciently how these mega-developments would turn out: “They will be clean, impressive, and monumental. They will have all the attributes of a well-kept, dignified cemetery. And each project will look very much like the next one…no hint that here is a city with a tradition and flavor all its own.” Each venue at 4th Street Live! is just like the venues at other Cordish Companies entertainment developments and the Marriott hotel’s architecture bears an uncanny resemblance the same hotel building in Indianapolis. (In this last case, a successful fight by preservationists, myself included, helped rebuild a facade of one of the demolished buildings on the corner of Third and Jefferson streets.)

“These projects will not revitalize downtown; they will deaden it,” Jacobs added. “For they work at cross-purposes to the city. They banish the street. They banish its function. They banish its variety.”

I don’t mean to compare Louisville’s recent large-scale developments outright to the mega-projects Jacobs is lamenting. The proposals from decades past were often far more destructive. But Louisville’s big proposals today are equally changing the nature of the city. And we must make sure we know exactly how. Jacobs’ lessons are certainly just as applicable today as they were half a century ago.

Jacobs was not anti-development, either—and neither are we. She just wanted development done right. Writing from a 1958 lens, Jacobs said, “Downtown does need an overhaul, it is dirty, it is congested. But there are things that are right about it too.” From her essay:

There are, certainly, ample reasons for redoing downtown—falling retail sales, tax bases in jeopardy, stagnant real-estate values, impossible traffic and parking conditions, failing mass transit, encirclement by slums. But with no intent to minimize these serious matters, it is more to the point to consider what makes a city center magnetic, what can inject the gaiety, the wonder, the cheerful hurly-burly that make people want to come into the city and to linger there. For magnetism is the crux of the problem. All downtown’s values are its byproducts. To create in it an atmosphere of urbanity and exuberance is not a frivolous aim.

…

We are becoming too solemn about downtown. The architects, planners—and businessmen–are seized with dreams of order, and they have become fascinated with scale models and bird’s-eye views. This is a vicarious way to deal with reality, and it is, unhappily, symptomatic of a design philosophy now dominant: buildings come first, for the goal is to remake the city to fit an abstract concept of what, logically, it should be. But whose logic? The logic of the projects is the logic egocentric children, playing with pretty blocks and shouting “See what I made!”–a viewpoint much cultivated in our schools of architecture and design. And citizens who should know better are so fascinated by the sheer process of rebuilding that the end results are secondary to them.

…

You’ve got to get out and walk. Walk, and you will see that many of the assumptions on which the projects depend are visibly wrong.

Much of what Jacobs was writing about was symptomatic of the 1950s and 1960s development scene—namely the suburbanization of downtowns, but the larger issues appear to still be with us today. Nearly every view the public is offered of a mega-project proposed in Louisville today is a sky-high aerial view that offers no ideas of how the development would affect the part of the city we all know best: the street. And Jacobs knew the building blocks of a city were small—beginning with the street.

“The best place to look at first is the street,” Jacobs said. “The street works harder than any other part of downtown. It is the nervous system; it communicates the flavor, the feel, the sights. It is the major point of transaction and communication. Users of downtown know very well that downtown needs not fewer streets, but more, especially for pedestrians.”

Creating a working lively street is complicated. “The whole point is to make the streets more surprising, more compact, more variegated, and busier than before—not less so,” she said. In another point as applicable today as in the 1950s, Jacobs noted:

It is not only for amenity but for economics that choice is so vital. Without a mixture on the streets, our downtowns would be superficially standardized, and functionally standardized as well. New construction is necessary, but it is not an unmixed blessing: its inexorable economy is fatal to hundreds of enterprises able to make out successfully in old buildings. Notice that when a new building goes up, the kind of ground-floor tenants it gets are usually the chain store and the chain restaurant. Lack of variety in age and overhead is an unavoidable defect in large new shopping centers and is one reason why even the most successful cannot incubate the unusual–a point overlooked by planners of downtown shopping-center projects.

Jacobs went into detail on how to approach the street:

Let’s look for a moment at the physical dimensions of the street. The user of downtown is mostly on foot, and to enjoy himself he needs to see plenty of contrast on the streets. He needs assurance that the street is neither interminable nor boring, so he does not get weary just looking down it. Thus streets that have an end in sight are often pleasing; so are streets that have the punctuation of contrast at frequent intervals. Georgy Kepes and Kevin Lynch, two faculty members of M.I.T., have made a study of what walkers in downtown Boston notice. While the feature that drew the most comment was the proportion of open space, the walkers showed a great interest in punctuations of all kinds appearing a little way ahead of them–spaces, or greenery, or windows set forward, or churches, or clocks. Anything really different, whether large or a detail, interested them.

Narrow streets, if they are not too narrow (like many of Boston’s) and are not choked with cars, can also cheer a walker by giving him a continual choice of this side of the street or that, and twice as much to see. The differences are something anyone can try out for himself by walking a selection of downtown streets.

This does not mean all downtown streets should be narrow and short. Variety is wanted in this respect too. But it does mean that narrow streets or reasonably wide alleys have a unique value that revitalizers of downtown ought to use to the hilt instead of wasting.

…

Most redevelopment projects cannot do this. They are designed as blocks: self-contained, separate elements in the city. The streets that border them are conceived of as just that–borders, and relatively unimportant in their own right. Look at the bird’s-eye views published of forthcoming projects: if they bother to indicate the surrounding streets, all too likely an airbrush has softened the streets into an innocuous blur.

…

But the street, not the block, is the significant unit. When a merchant takes a lease he ponders what is across and up and down the street, rather than what is on the other side of the block. When blight or improvement spreads, it comes along the street. Entire complexes of city life take their names, not from blocks, but from streets–Wall Street, Fifth Avenue, State Street, Canal Street, Beacon Street.

…

Backers of the project approach often argue that giant superblock projects are the only feasible means of rebuilding downtown. Projects, they point out, can get government redevelopment funds to help pay for land and the high cost of clearing it. Projects afford a means of getting open spaces in the city with no direct charge on the municipal budget for buying or maintaining them. Projects are preferred by big developers, as more profitable to put up than single buildings. Projects are liked by the lending departments of insurance companies, because a big loan requires less investigation and fewer decisions than a collection of small loans; the larger the project and the more separated from its environs, moreover, the less the lender thinks he need worry about contamination from the rest of the city. And projects can tap the public powers of eminent domain; they don’t have to be huge for this tool to be used, but they can be, and so they are.

…

The developers and architects have a point. They have a point because government officials, planners–and developers and architects—first envisioned the spectacular project, and little else, as the solution to rebuilding the city. Redevelopment legislation and the economics resulting from it were born of this thinking and tailored for prototype project designs much like those being constructed today. The image was built into the machinery; now the machinery reproduces the image.

…

The project approach thus adds nothing to the individuality of a city; quite the opposite–most of the projects reflect a positive mania for obliterating a city’s individuality.

For Jacobs, a city’s core—all of it—must be considered equally as a livable place packed with activity. There’s no exception to carve up each piece of a city into niches and micro-districts that specialize in only one thing.

It should be unnecessary to observe that the parts of downtown we have been discussing make up a whole. Unfortunately, it is necessary; the project approach that now dominates most thinking assumes that it is desirable to single out activities and redistribute them in an orderly fashion–a civic center here, a cultural center there.

But this notion of order is irreconcilably opposed to the way in which a downtown actually works; what makes it lively is the way so many different kinds of activity tend to support each other. We are accustomed to thinking of downtowns as divided into functional districts–financial, shopping, theatre–and so they are, but only to a degree.

Ultimately, Jacobs wanted to see average citizens step up and influence the development of the city around them. “The remarkable intricacy and liveliness of downtown can never be created by the abstract logic of a few men,” she said. Much of her legacy is that citizen engagement has increased and awareness of what makes a good city—a good street—has never been higher.

Jacobs encouraged citizens to ask tough questions of these mega-projects. It’s their city, after all. “Downtown has had the capability of providing something for everybody only because it has been created by everybody,” Jacobs noted.

In short, will the city be any fun? The citizen can be the ultimate expert on this; what is needed is an observant eye, curiosity about people, and a willingness to walk. He should walk not only the streets of his own city, but those of every city he visits.

And so we’ll continue to keep our eyes peeled along the Broken Sidewalk. Read Jacobs’ entire essay here.

My only quibble is with the success of third and Jeff – we got one facadomy and about eight demolitions…… Including Kings Record Shop (see Roseanne Cash’s CD of same name), and the Penguin, and lots of buildings gone porn. ( the best way to tear it out is to demean it while its still there) The old Jewish retail center.

Sadly some of us DO remember what was and what ain’t and what stupid repetitive mistakes will once again be made in the name of the Next Great Thing.

And my copy of Jane cost $1.95. Shows how long some of us have been clutching!