Think about your favorite places in Louisville—a restaurant, a bar, a beautiful walk. Where do you take out-of-town guests when they visit? Chances are most of those places are shaped by the city’s historic building fabric and the fine-grained pattern of development that shaped them. They’re places that, well, keep Louisville weird.

Garage Bar works because it’s in a quirky old building with peeling paint. It just wouldn’t be as fun if it were in a strip mall looking out onto Hurstbourne Parkway. Ramsi’s Cafe works because you can walk right up to it from a coffee-shop-slash-bookstore or from your own apartment a couple blocks away. It’s just hard to think that Proof on Shelbyville Road Plaza would have the same cache as Proof on Main.

While it’s the local business we’re attracted to in these examples, it’s the historic fabric and its “local business friendly” qualities that help make those establishments possible. Louisville’s independent culture has been built on the backs of its historic building stock. Which makes me scratch my head when we continue to carelessly throw those future homes of local businesses into the trash heap.

Preservation at a turning point?

Lately in Louisville, though, there’s been a galvanizing of the community to keep ahold of what’s left—not just as a relic of the past, but as a tool of a modern economy. For a long time, the redevelopment of Whiskey Row felt like it might never happen—and at many points the buildings were on the brink of destruction. But with the groundbreaking of the Old Forester Distillery and the already active Whiskey Row Lofts, the block is on the up and up. Those braces holding up the fire-ravaged shell of another set of old buildings awaiting renovation are a testament to how resolute we are in saving a piece of a the city’s and bourbon’s history and identity.

Having watched Whiskey Row evolve over the past decade, I’m delighted to see the same tenacity at work uniting the community over a building that gave us another of our cherished liquids—crystal clear water. The old Louisville Water Company Headquarters on Third Street has become a uniting symbol for a community that chooses local first.

For months now, Louisville’s top minds in development, architecture, sustainability, urbanism, and preservation have been crunching the numbers, sketching design ideas, and making the connections to save the proud structure in one form or another, and there have been ups and downs along the way.

This place matters

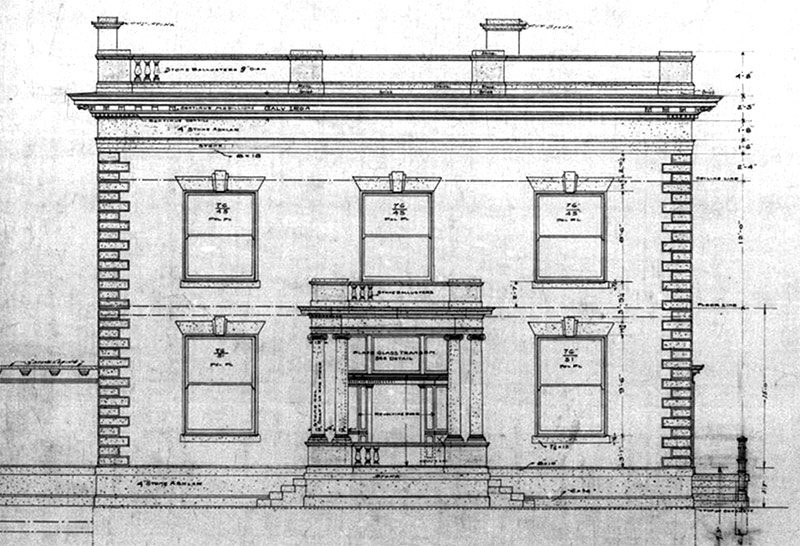

The Headquarters was built in 1910 by architect Theodore A. Leisen with a monumental scale that reflected the ambitions of the company’s new chief Sebastian Zorn, who was embarking on a quest to modernize Louisville’s water system, leading to today’s internationally recognized water company. The clean detailing and simple lines of the Colonial Revival structure and its refined Ionic columns framing a front stoop would have appeared strikingly modern a century ago in a city still bedecked in Victorian trappings. The building is only two stories tall, but its oversized elements and the distinctive longer-flatter proportions of its beige Roman brickwork hide the fact that it’s the size of an ordinary four-story building.

You can literally pour the heritage of this building from your tap.

It’s now or never for the Water Company Building

But Mayor Greg Fischer’s stopwatch is ticking out of time for the Water Company Headquarters. In May, the mayor pledged $1 million in city funds to relocate the building, which sits in the way of the loading dock of the just-approved $300 million Omni Hotel & Residences. “The bottom line is we are committed to saving all or parts of the historic old Water Company Building,” Fischer said in May. With a 30-day deadline, he called on the community to offer up feasible ideas to move the building within a six-block radius.

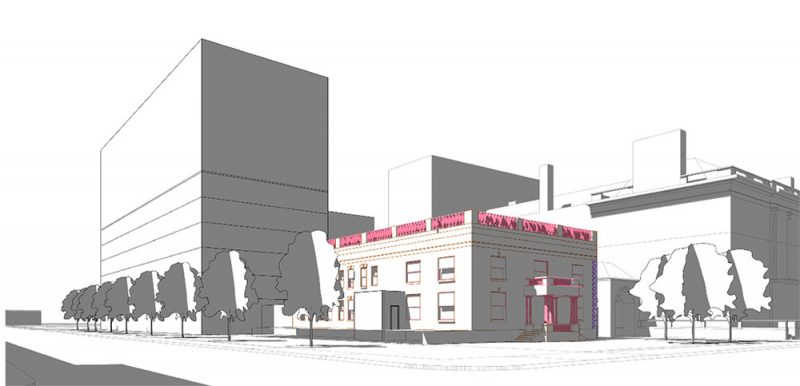

The community sprang into action, organizing a design charrette co-hosted by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Dozens stepped up to detail four sites that would readily fit the headquarters building—Founders Square, the southeast corner of the Omni block, a parking lot next to the Pendennis Club, and a remnant space adjacent to Interstate 65 at First Street—and put together an extensive report for the mayor.

It’s Louisville’s great fortune that so many in the community care enough to step up and help, and the ideas generated at the charrette are exciting in their possibility for the city. Moving the building would be a chance to knit back together the city’s urban fabric, pocked by decades of demolitions leaving parking lot scars. The Water Company Headquarters could fill in one of those missing teeth, and in turn be filled by a local business.

The hard work put into the charrette helped extend the mayor’s deadline and gave credence to several development proposals by local and out-of-state developers. Those groups continue to work on their relocation plans to this day.

Why dismantling just won’t work

But a new, more ominous deadline is approaching. One week after the Downtown Development Review Overlay voted to allow the city clear the site, the mayor issued an open letter to the community saying he is moving forward to do just that. Private interests submitted their proposals to the administration, which reviewed the top three, but the mayor said plainly Wednesday that “no workable proposals have been offered.” He continued: “These proposals were not accepted because they either required city tax dollars in addition to the $1 million already committed, had feasibility issues, or did not effectively reuse this historic building.”

Instead, the city plans to dismantle “the facade, portico and a portion of the side walls” and place them in storage. This has dire consequences for the future of the building—not to mention no building ever put in storage has reemerged. A critical part of redeveloping the Water Company Building at a different site is the availability of federal and state historic tax credits. These tax credits are already thrown in jeopardy by a move, but would be lost entirely if the building were dismantled and moved far away.

Healthy Urban Design, a citizen group that emerged from the charrette, was “disappointed” by the mayor’s letter:

Mayor Fischer has been cooperative up to today in offering businesses and individuals an opportunity to develop projects that would permit the Water Company building to be transported to another site. Yet as he and the leaders of Louisville Forward know, or should know through the advice of their Landmarks and Historic Preservation office, historic buildings cannot be dismembered and stored like so many Legos from one location to another.

The mayor’s economic development team, Louisville Forward, it would appear, has been instituted without a rear-view mirror. Such a culturally significant structure, with so much potential as an economic contributor, deserves the full attention and support of the city.

We requested the three proposals from the city, and spokesperson Jessica Wethington said they would be released soon. “The city is confident that we have done everything we could to support preservation/moving the building,” Wethington said in an email.

Don’t give up just yet

There’s still time for a move, however. The city filed for demolition permits this week, and those permits carry a 30-day stay-of-demolition. That gives developers time to refine their proposals and continue their push to save the building. And the development teams I spoke with this week are doing just that, remaining optimistic that a solution can be found.

But ultimately, the entire process hinges on whether or not the mayor will make a stand in support of the community. “Preservation of our city’s historic sites is a value of my administration,” the mayor said in his letter Wednesday. Let’s stand up for that value by finding a way to move the old Water Company Headquarters to a site where it can contribute to the city’s well being for generations to come.

Please take time to contact Mayor Fischer and let him know that saving the Water Company Headquarters should be a priority for a community-funded project like the Omni.

If they can’t find a suitable place downtown to move the building, what is wrong with moving it to another current water company property, like near the water tower and pumping station at Zorn ave, or the main water company on Frankfort Ave. Both locations have plenty of land to relocate it.