Steve Smith bought Louisville Stoneware eight years ago. Ever since, he’s been dreaming of how to make the 200-year-old company relevant in the 21st century. Last week, that dream was unveiled as a dynamic arts and culture hub that would remake the tiny Paristown Pointe neighborhood into the centerpoint of Louisville’s quickly developing inner ring suburbs.

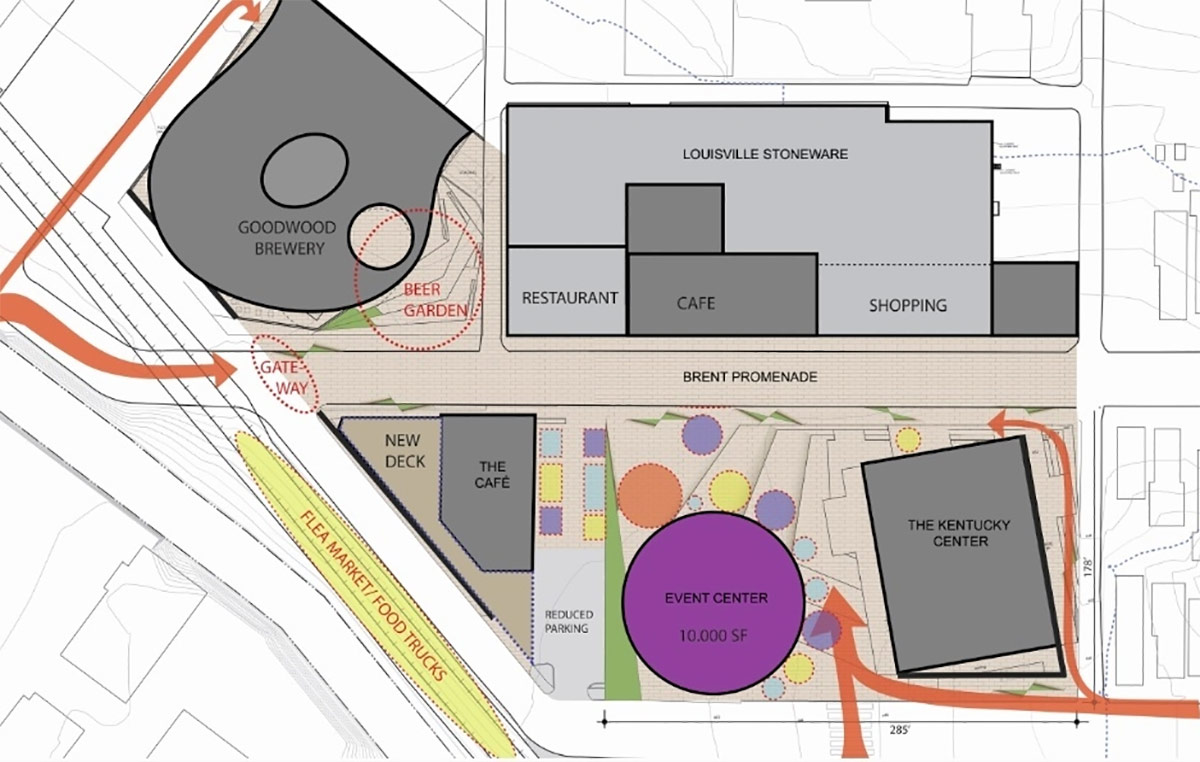

Smith enlisted Los Angeles architecture firm wHY and a cadre of local designers to chart the path under the banner of the Paristown Pointe Preservation Trust. The $28 million plan calls for redoing the historic Stoneware headquarters, building a major production brewery and restaurant operated by Goodwood, and, the centerpiece, a 2,000 capacity theater for the Kentucky Center for the Arts.

Broken Sidewalk’s Branden Klayko spoke with Smith about the project after the public unveiling to learn more about Stoneware’s cultural significance for Louisville and the nation over the past two centuries that makes it worth the investment.

You have described how Stoneware helped shape a young United States two centuries ago. How did Stoneware’s story begin?

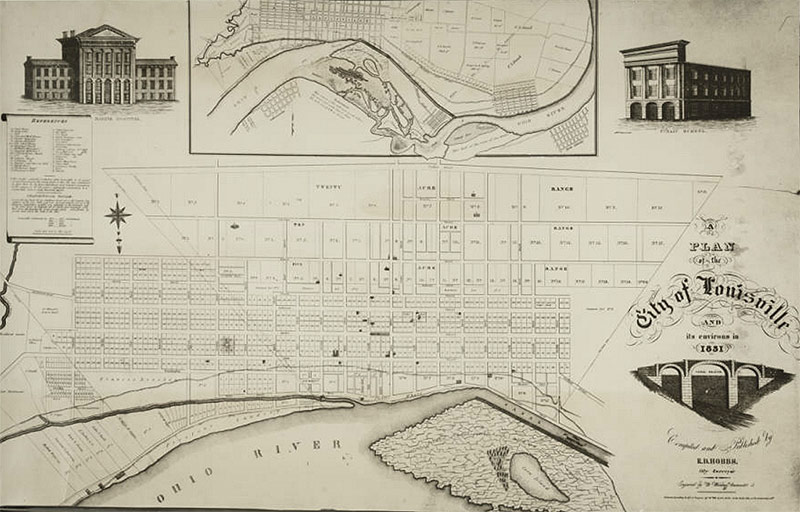

1815 was an important year for Louisville, Kentucky. Louisville was a sleepy little river town with very little strategic or economic importance in 1815. Basically because river traffic was one way. The early settlers lived on creeks, and would float flatboats to the Ohio River for a one-way trip down to New Orleans. And the trip back was pretty precarious. Most people walked back. Or you could buy a horse and ride back. But that was how early products like bourbon got to New Orleans.

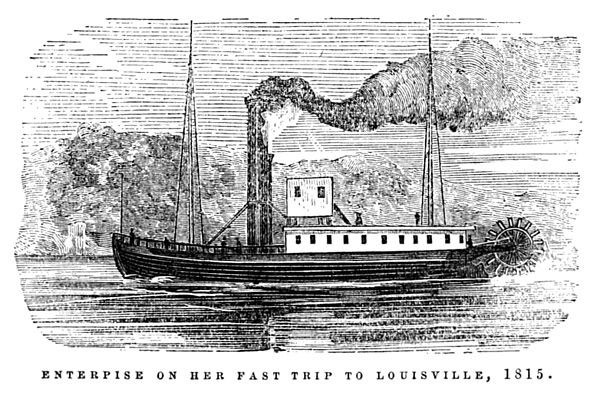

In 1815, you’ve got the end of the Napoleonic wars in Europe. That allows immigrants to come to the United States for the first time in a couple decades. And then you’ve got the end of the war of 1812, which brings about the end of Indian hostilities in the Ohio River valley. Then a small steamboat, the Enterprise, made it from New Orleans to the bottom of the Falls of the Ohio.

So you’ve created a sort of perfect storm, you’ve got the land from the Louisiana Purchase being hocked all over the world, and so you can come to America, land in Philadelphia, Boston, or New York, come down the Ohio River safely. The last stop you’ve got is Louisville, Kentucky before you head downriver to settle the farmlands.

How did Stoneware help settle the American West?

If you’re going to go live in a cabin on the range for a couple years, you’re going to need salt to cure your meats, and you’ll need sugar to survive and make a little corn whiskey on the side.

The only safe way to store your most precious items would have been in a stoneware crock. For the past couple thousand years, it’s been the safe storage container. They would take these big 30 gallon crocks with big lids on them, and they would pull a hide over the top and tie it with a rope, to keep gnats, mice, rats, different animals out.

And Louisville is where you’d buy the stoneware?

This guy named Jacob Lewis started a pottery company on the Falls of the Ohio, and unbeknownst to him, he would create the largest stoneware factory in the United States at one point. Places like New York, Philadelphia, all these places had stoneware factories, but because of the Westward migration, Louisville’s population doubled in size every ten years all the way up to the Civil War.

What about after the West was settled?

Then you come to the end of the Victorian era and canning and bottling take over as major storage. Nobody wants big, 150-pound crocks anymore. But the rise of the middle class brings about the need for everyday dishware, which was kind of unheard of back then. Our founding fathers, they all ordered their blue-and-white porcelain or fine English china and the average person lived off a tin plate.

The guys who owned the pottery, which was probably the Bauer Company at that point, had to change and innovate and move with the times. And they started making everyday dishes.

That lasted all the way up until the ‘70s until you saw the fleeing of manufacturing from the United States. The factory, from what I understand from the previous owners, had 250 people and it went down to 25 or 30. The cost for us to make a coffee mug in the U.S. is about $12. You can go to Starbucks and buy coffee cups for 5 or 6 dollars. We’re paying a living wage and health insurance, and all these other people are paying $200 a month for labor in Vietnam.

Is that why you’re launching the cultural district?

I’ve been here for 8 years, and really tourism keeps us going. We’re the oldest continually operating pottery company in America. I call the place a Great American Treasure—we’re the last great standing American pottery. The only way I knew how to survive was to try to create a destination where people could come here and we could do factory tours and we could educate people on how this stuff was made for the last 200 years in America.

Really, that’s why we got in touch with Kulapat and wHY. And looked for an anchor tenant, which we got with the Kentucky Center for the Arts. We had a lot of great energy at the press announcement. The city, the state, everybody’s behind it.

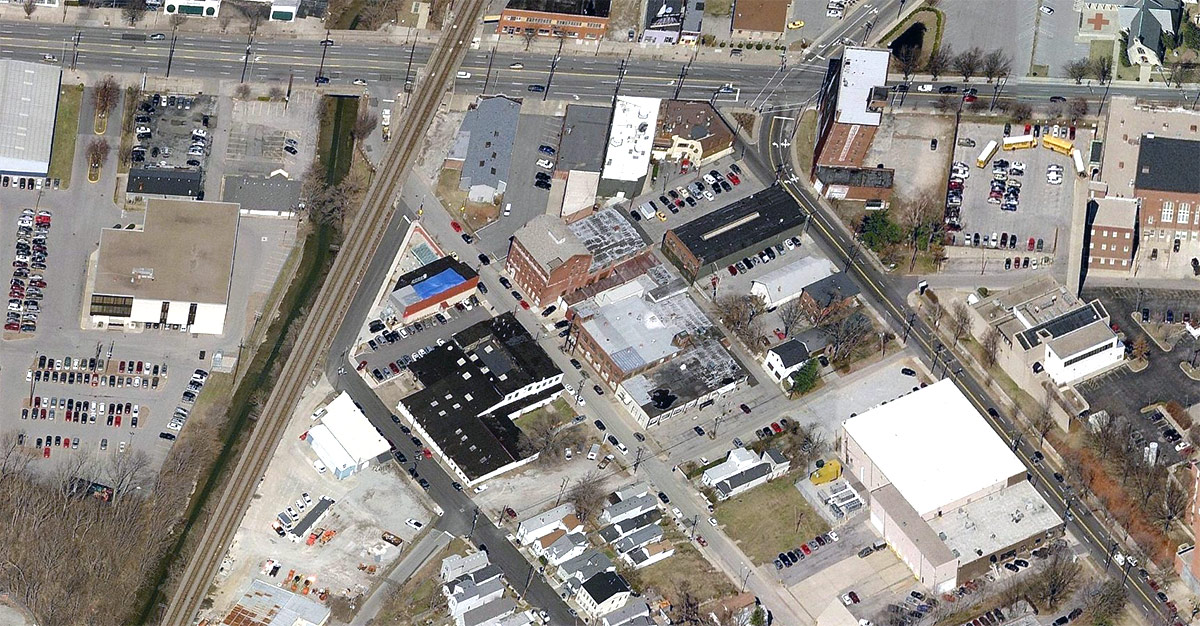

Paristown Pointe is such an interesting neighborhood for such a project.

It’s fascinating, because when I started talking about Paristown Pointe with the people at the city, they were like, what are you talking about? I mean, the neighborhood had been lost to time. Nobody had heard of it. It’s been standing here for over 200 years and nobody’s really cared. With Kulapat, we get the opportunity to reimagine the neighborhood.

If you’ve ever been back in this little enclave, there’s a railroad trestle that protects it and it’s kind of a hidden place. We don’t have traffic running through the middle of the streets—we can shut down the street and do a street fair or an art fair very easily.

Since it’s in such bad disrepair—nobody’s cared for so long—we’ve been able to acquire property at reasonable rates. And we’ve been able to reimagine a great start to turn this neighborhood around.

It’s a group of individual people all partnering to make this happen. It’s not a big development group. We’re just a bunch of people who love this town. And care about the people and the architecture and and the sustainability of where we raise our children. I think this is a great opportunity to give those children a reason to stay here.

For me, I’ve been talking about this for 8 years and really working on it for the past four or five, so it’s just amazing to see.

A little investment here goes a long way.

This is not about us. This is about the neighborhood, about the people who work at Stoneware. And we want this to be a place where everyone in Louisville wins. We want the residents to win, the employees at all these places to win. We want to create jobs, we want to do the right thing.

And we’re going to add jobs. We’ve got two Hope VI redevelopments around the corner. We’ve got lots of people within a ten minute walk that need a job. The jobs are going to be between $10 and $15 an hour. We’re going to open up restaurants, we’re going to have the coolest place in town to be.

But you still need to get tax credits to move forward?

So what we have to do is something called a Tourism Tax Credit in the state of Kentucky. Where we can recover up to 25 percent of the cost of the project through growth of tax revenues. You’ve got to earn the money—it’s not like they’re just giving you free money. And then we’ve got some historic tax credits with the Stoneware building.

We’ve had our first meeting with the neighborhood association a few weeks ago. As we go through the different stages, we’ve got to get all of our budgets in line first, which is what we’re working on right now. The Kentucky Center is a state agency, so they have a certain process that they go through—that they’re going through right now.

From what we’ve heard, there are some serious sustainable ideas going on here.

We think with the right architecture and landscape architecture, we can restore what I’m calling the Creek District with native grasses and native trees. We’re trying to turn it into a parking-lot-slash-bird-sanctuary, if you will. We need to make sure we’re providing enough parking so that we can protect the little village that’s here.

We’re working with MSD to make sure we’re retaining all our storm water. We’re using sustainable practices in terms of architecture and making sure we’re protecting the environment in terms of stormwater runoff.

The city has been very supportive in putting in new roads, what I’m calling the public safety and infrastructure improvements.

And then we’ve got arts and entertainment.

Why is this theater so special?

The fortunate part of having the Kentucky Center as our partner is they’ve got this huge mission in the state of Kentucky—they’re a quasi-state agency. They’re funded by the bed tax so they’re a very stable partner for us.

Mainly their building is for young people. It’s a House of Blues–type venue for 21 to 35 year olds. It’s a 2,000 person, standing room only facility. There’s a lot of programming with the Kentucky Center. Teddy Abrams with the Louisville Orchestra wants 25 dates there. It’s going to be a mix.

It’s interesting that as they talk about this facility, the orchestra is getting excited, the ballet is excited, all the cultural arts groups in town are saying this is a perfect small space where we can do smaller things and we don’t need this big behemoth stage and all this other stuff. It become much more of an interpretive opportunity.

The old Stoneware building is getting an overhaul, too.

What we want to do is create a very authentic place where people can bring their families, to become an educational destination. Part of our renovation, we’re going to expand our paint your own studios. We’ve got a lot of social things we want to do as well.

The idea is how do we make the place live—let it survive. We have an economic problem that prevents that from happening now.

We’re working with Kulapat and wHY on upgraded designs. We need new creativity, we need to create the next look and feel because most people have the perception that what we’re doing is pretty old and tired. Some people love it, but we don’t get a lot of young people walking in the door right now and that’s what we need.

It takes a village.

Exactly.

So much for the negatives applied to preservation ( which is the original sustainability in this city) as a loser in economic development . We have (for now) one of the best opportunities to create vital linkages and connectivity from commercial corridor to commercial corridor using much of the existing built environment to do so.

Edwards Company, pay attention.

When do they plan on finishing the project.

Is there a website associated with the project so that we can track progress?

I think this is an awesome idea.

So no mention of John B Taylor at all. Are you from Louisville? Do you know pottery at all? I will not buy it anymore because you have wiped out all the history with Louisville and our pottery company. Now stoneware and co not Louisville stoneware which was known world wide. The old building was great we could talk to the people making the pottery and see them paint it. They always had popcorn and you could grab a glass of water from one of their crocks while deciding on which piece of pottery you needed most in your collection. And you could tour the whole process. I miss Louisville stoneware. Now it’s just a shop on the side of a restaurant just a store nothing else. Collateral damage a guess to your plans. No interaction with anyone. You sir have destroyed a landmark here and I am certain that many people agree.