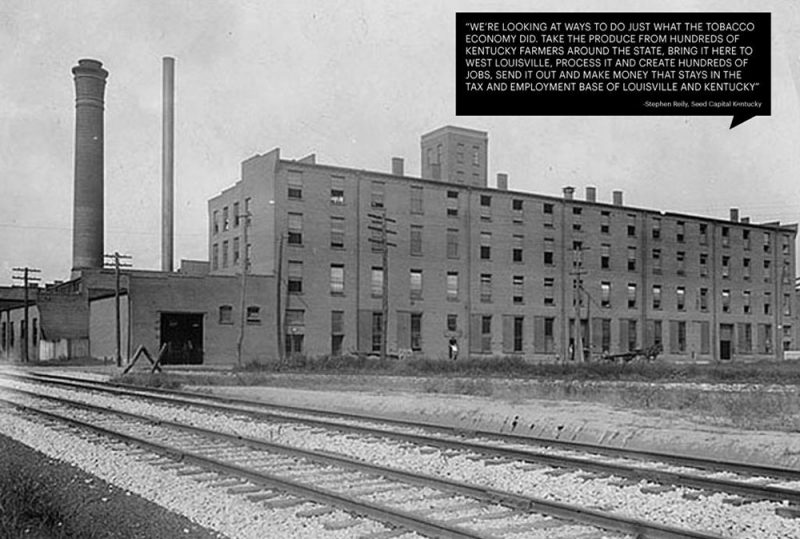

Three years ago, a massive industrial site in West Louisville’s Russell neighborhood was bleak and looking bleaker. Wrecking crews were ripping out a complex of 19th century warehouses at 30th Street between Market Street and Muhammad Ali Boulevard that once housed the National Tobacco Company. The plan back then was to build an uninspiring industrial park anchored by a concrete company and walled off from the neighborhood by a berm. After those plans fell through, the empty 24-acre site languished as an eyesore in a neighborhood burdened by more than its fair share of blight.

Where that cement factory was planned, however, the concrete is being peeled back and the site will soon be reborn as the West Louisville Food Hub, thanks to a partnership between Seed Capital Kentucky—a non-profit dedicated to growing Louisville’s local food economy—and Metro Louisville.

“A regional food hub is,” according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, “a business or organization that actively manages the aggregation, storage, distribution, and marketing of source-identified food products primarily from local and regional producers to strengthen their ability to satisfy wholesale, retail, and institutional demand.” But Louisville’s $46 million food hub is expected to be much more than a distribution hub for local farmers, with plans for on-site farming, processing, recycling, education, and retail.

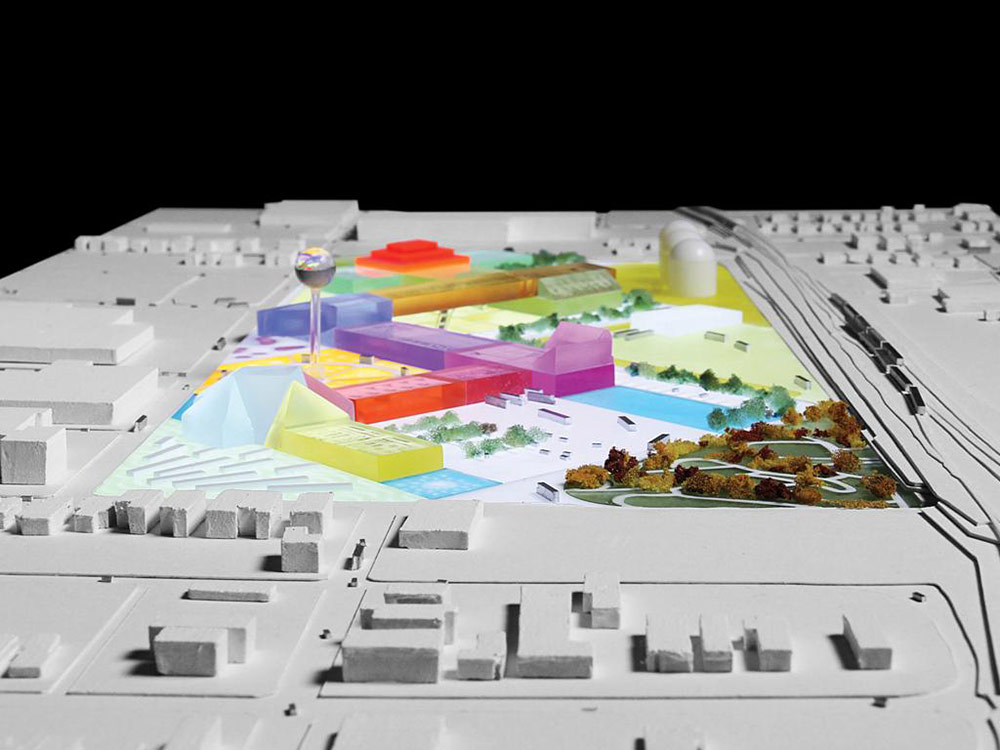

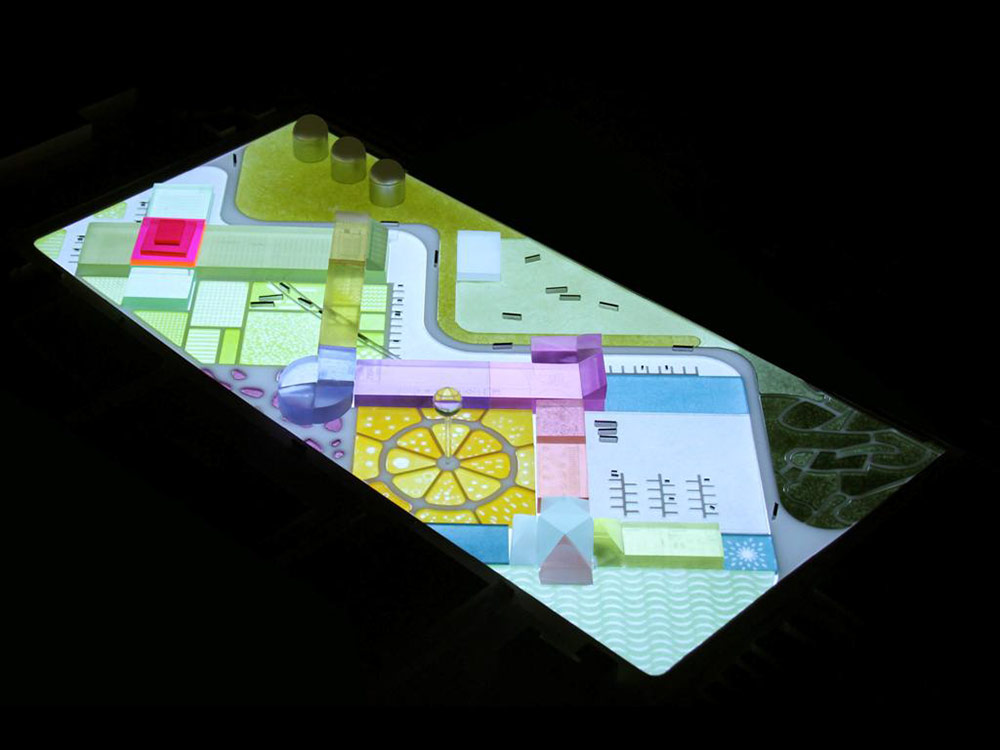

Seed Capital has asked internationally renowned architects at OMA, the Office for Metropolitan Architecture, to imagine what that kind of facility might look like, and their design knits together a complex program of green industry and public engagement. A new master plan just released by Seed Capital shows a zigzagging complex that is expected to be under construction later this year.

“OMA is a very renowned firm,” Seed Capital Project Director Caroline Heine told Broken Sidewalk. “There was something unique about them, which is that they are engaged in a multi-year study of the relationship between food and design and architecture through a course at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.” OMA Principal Shohei Shigematsu and architect Christy Cheng taught an architecture studio at the university where Louisville’s food hub was among the focuses.

And if OMA sounds familiar to you, that’s because it should: the firm previously designed the ill-fated Museum Plaza before its New York office split to become REX. Heine said Seed Capital, founded by Heine and Stephen Reily, selected OMA to design the Food Hub following a limited request for proposals that generated interest from five firms. She declined to name the other firms that were interviewed for the project. OMA is working with the Louisville office of GBBN Architecture on the project.

“Two students in the Harvard course focused on our project,” Heine said. “They were responsible for doing their own research and their own design. By their final presentation, OMA had already been selected and was already working on the master plan concept for the project. The research the students did was, of course, helpful for Christy and Sho’s work on our project.”

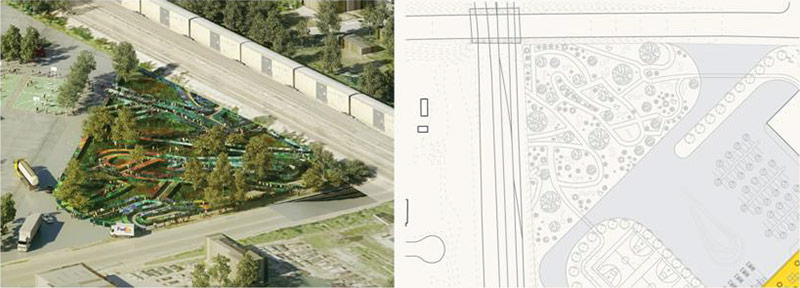

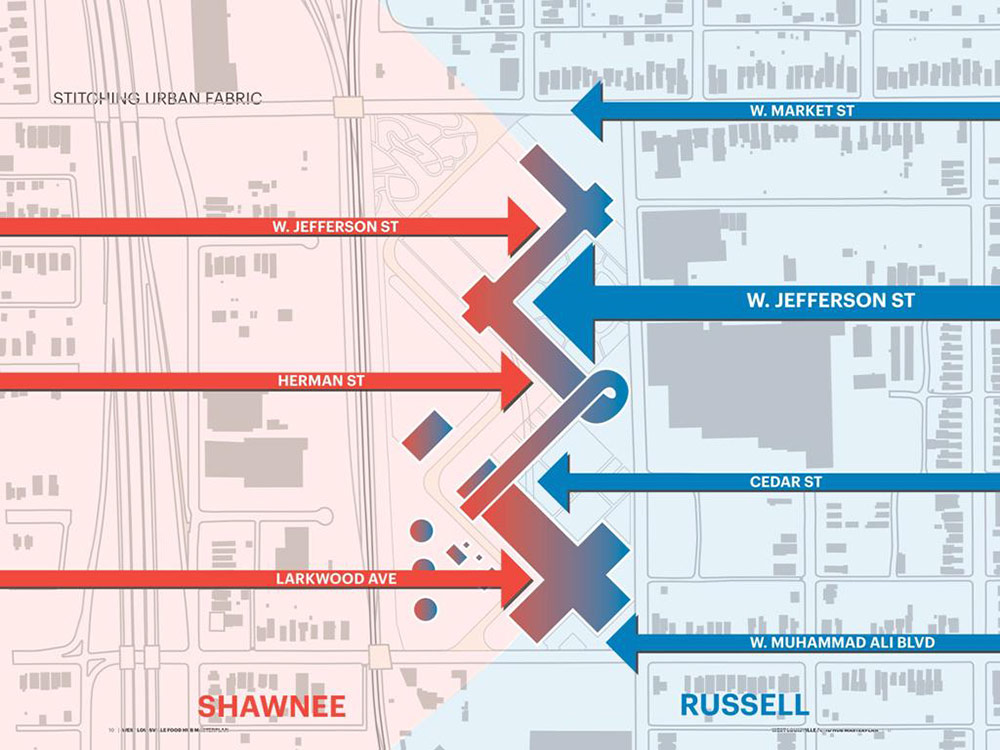

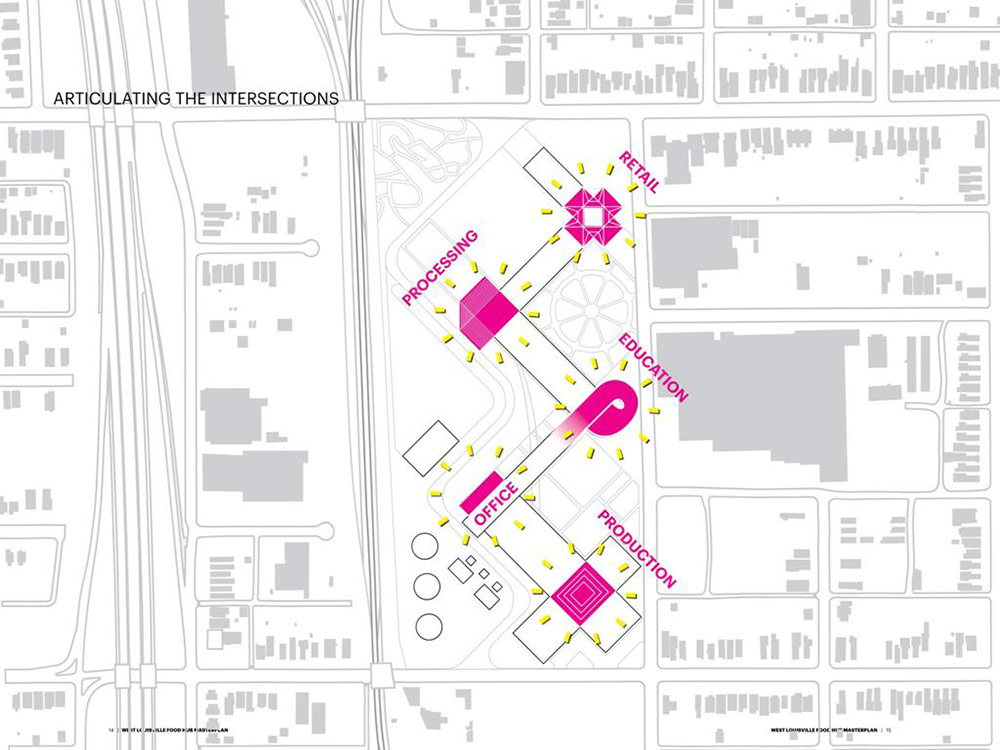

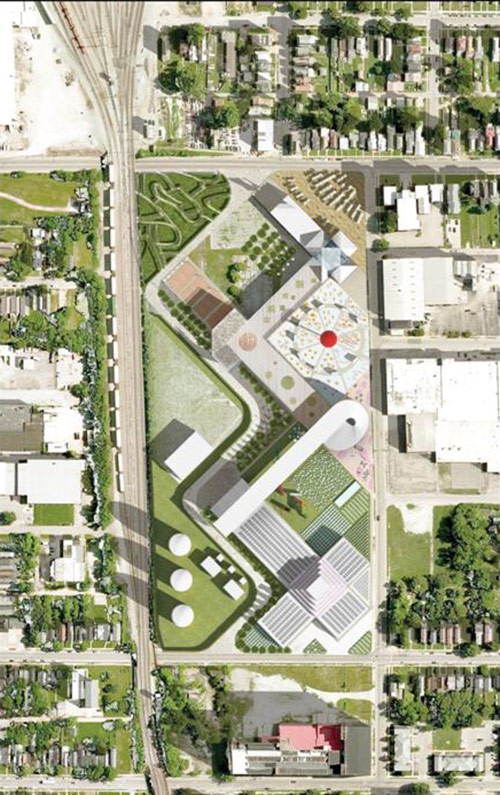

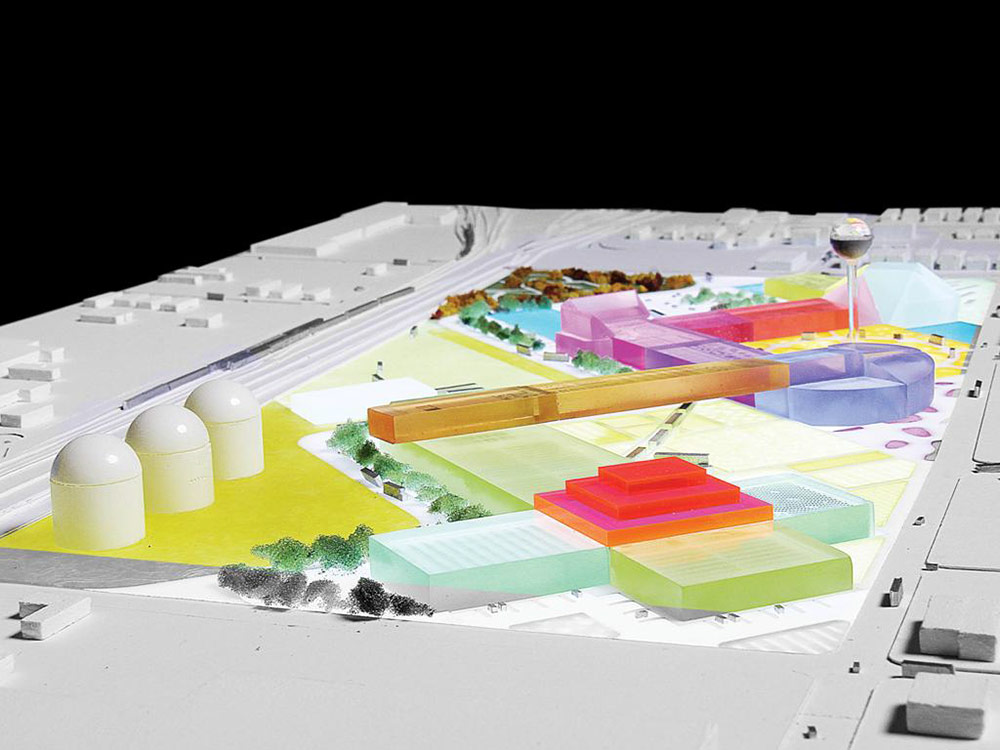

Bounded by Market Street, 30th Street, Muhammad Ali Boulevard, and railroad tracks to the west, the Food Hub site at 3029 West Muhammad Ali Boulevard is a complicated design challenge in its own right. “OMA wanted to communicate with the existing street grid,” Heine said. “On the east side, three streets terminate into the site between Market and Muhammad Ali. On the other side of the railroad tracks, those streets don’t align on the same grid. In fact, they’re different streets entirely.” The architects used the shifting street grid as it follows the Ohio River to inform the zigzag shape of the facility. Where streets terminate into the site, a kink in the building provides a focal point.

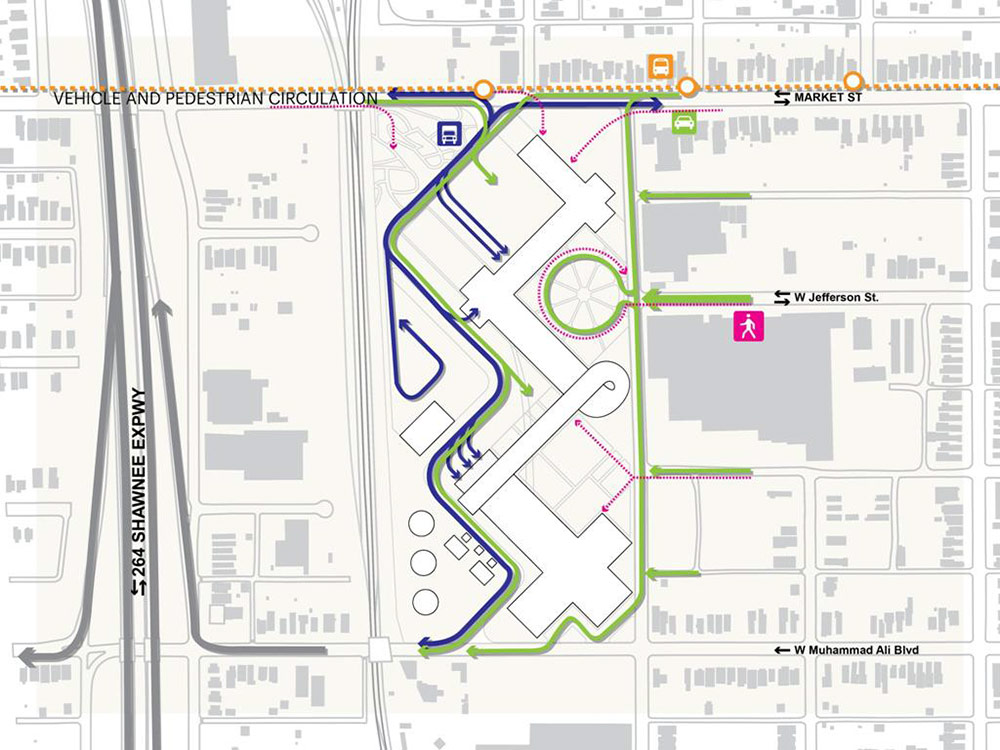

Combining an active industrial facility with spaces for the retail and public engagement also presents challenges. “The goal is to have a lot of people here all the time, whether it’s a market situation or an event situation,” Heine said. “At the same time, there are big trucks and logistics happening. The challenge was to design a campus where all of that can happen at the same time.” OMA’s design uses the hub buildings to organize the two sometimes-opposing components. “The concept uses the building as a barrier between the public-facing parts of the hub and the more logistics-heavy components, which are behind the buildings,” she continued. “Very much attention was paid to how to effectively and beautifully and safely have the various entities coexisting on the site.” Vehicular entrances are located on the north and south sides of the site, and large trucks will be screened by the hub buildings.

“OMA understood that because the site is so large and because of where it is, there were going to be multiple programs on the site—it’s not just a food hub,” Heine said. “The master plan is not only the design of the buildings but it’s about how the 24 acre site and its buildings relate to the community at large.”

As with all master plans, change is part of the process. “This is what the facility ultimately, ideally would look like, with opportunities for adjustments as needed,” Heine said. “We specifically asked OMA to plan so we could use a phased approach, knowing that this is a complex project and partners could grow and come on board during the planning process.” So far, four groups have signed up to be part of the West Louisville Food Hub:

- Nature’s Methane, a subsidiary of Star Distributed Energy, will operate an anaerobic digester that converts organic waste like compost to methane that will be sold to LG&E for conversion to energy.

- KHI Foods, a food processing company currently located in Burlington, Kentucky, will relocate to the hub and operate a vegetable processing facility.

- Jefferson County Cooperative Extension: which will relocate from its current location and operate a demonstration farm on site.

- The Weekly Juicery, a cold-pressed juice producer with retail outlets in Louisville, will operate a processing facility at the hub.

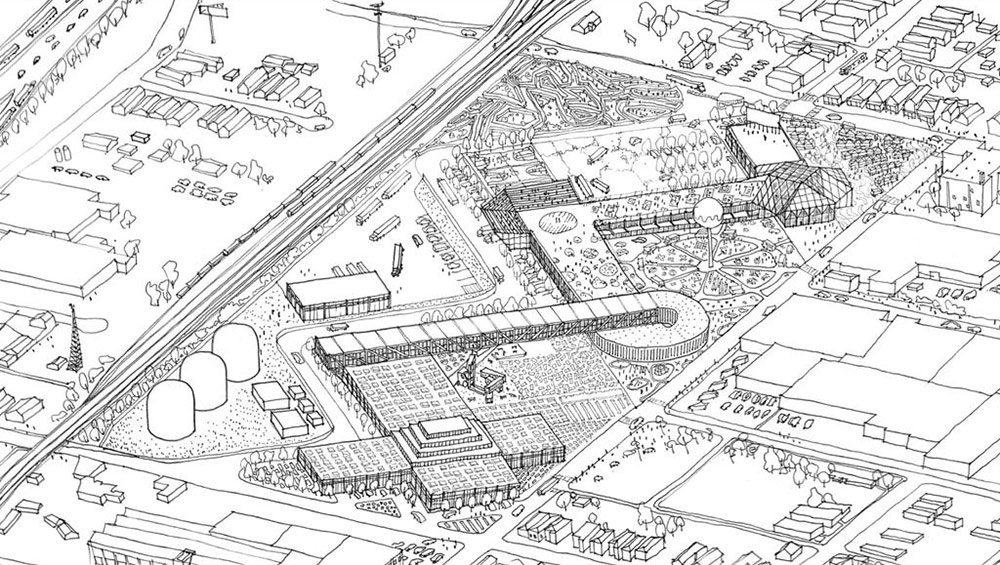

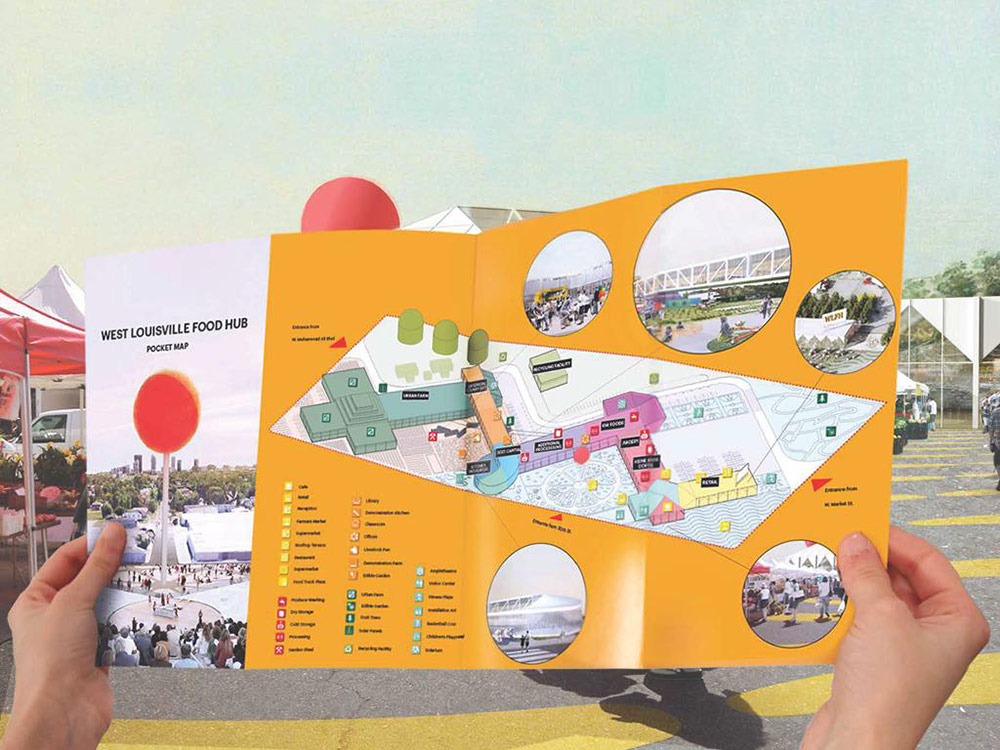

Beginning at the northeastern corner of the site on Market and 30th streets, a triangular Market Plaza will be one of the Food Hub’s prominent public spaces. Heine said the plaza would host a farmers market and pop-up retail with a public-facing building housing a visitors center and potentially other retail space. “We’re just beginning to think about all the opportunities there,” she said.

To the west is an Edible Garden, what’s intended as another opportunity for the community to participate in the site, adds a wedge of green space against the railroad tracks. Heine said the space could allow other organizations or community gardens to come into the site and grow edible plants. Basketball courts nearby provide recreation opportunities for employees and the public.

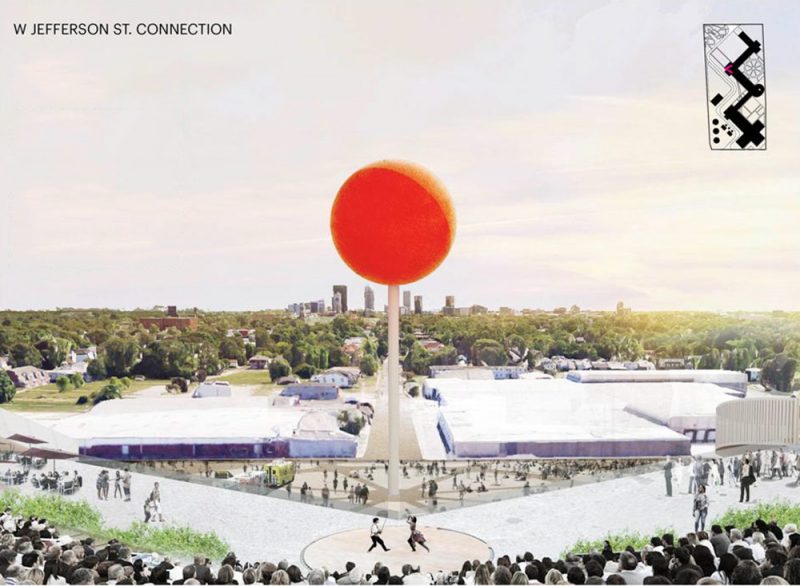

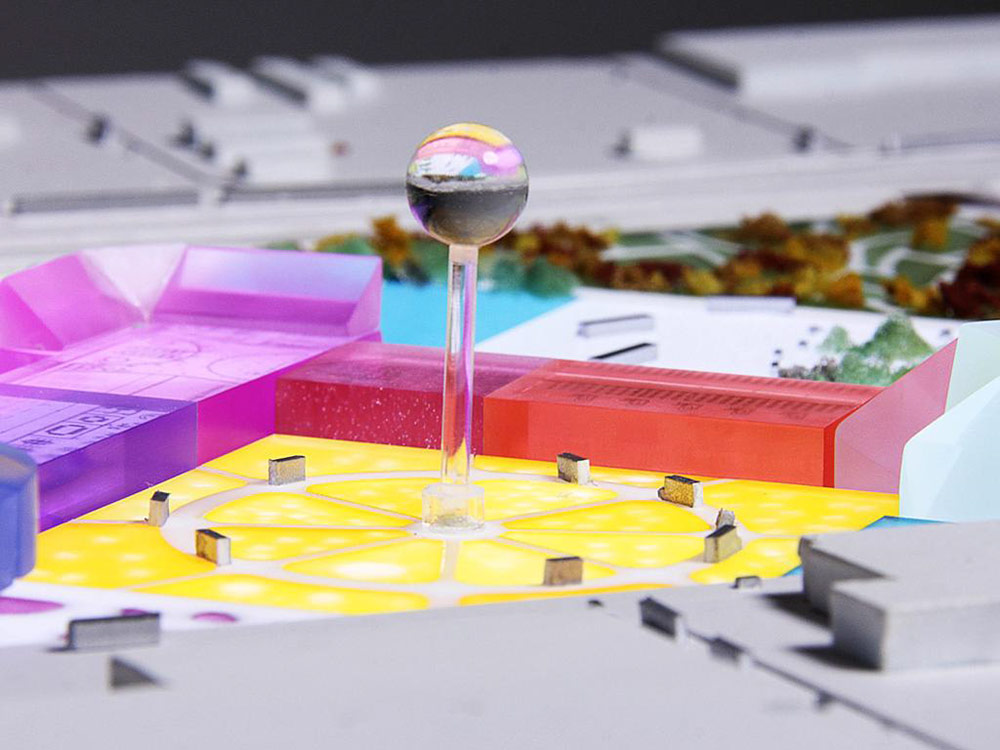

To the south, a public events plaza features a monumental pin-shaped water tower that collects rainwater and serves as a monumental view as Jefferson Street terminates on the site. “That’s where the event space is,” Heine explained. “The renderings show a food truck plaza, but it could also be used as an outdoor events space. And above that, there’s a rooftop amphitheater. You can imagine having an opportunity to be elevated a little bit and see views of Downtown Louisville facing east from the venue.” City Hall is a mere two miles—24 blocks—down the street.

According to OMA’s master plan, “The rotated grid is aligned to connect to the existing street grid and weave the site into the urban fabric. Rather than meeting the terminus of Jefferson St. with a building, a large “Food Truck Plaza” invites visitors and employees into the site and offers views into surrounding processing facilities.” The plan adds, “Given the visual connection to downtown Louisville, the public “Food Truck Plaza” aligns with the rooftop amphitheatre and [is] located along this visual axis. A water tower, used for stormwater retention, anchors the axis to downtown and echoes other vertical markers seen in Louisville and other food related facilities.”

South of the plaza, a circular corner of the building spirals up dramatically. It will include offices for Seed Capital Kentucky and other small companies, a classroom and community education kitchen, and a library is planned to line the circular walls. Outside, a community playground is planned to bring another layer of activity to the site.

At the top of the spiral, a glass-clad bridge spans the two-acre Demonstration Farm of the Jefferson County Extension Service. That group will relocate their offices from Barret Avenue to the bridge space. Heine said the architects were intrigued by an old rail spur that once entered the site and marked its history with a collection of rail containers near the demonstration farm that could display art, house pop-ups, or be used as storage. She called the move “a nod to the historic use of the site.”

According to OMA’s master plan, the Demonstration Farm itself is broken up into several spaces for raised beds, edible trees, chicken coops, and potentially grazing areas for sheep or goats.

Anchoring the southeastern corner, a cruciform mass could house a vertical indoor farm.

Finally, at the southwest corner, a series of biodigesters will convert organic waste into heat energy.

According to a report last month in Business First, the biodigesters “received preliminary approval for as much as $2.1 million in state tax incentives” from the Kentucky Economic Development Finance Authority. The facility will convert food waste into methane gas, providing enough electricity for about 3,200 homes. The Business First report said the biodigesters are expected to cost about $27.4 million and will create six jobs paying $42.50 an hour.

The Food Hub will help establish green roots in the Russell neighborhood, and the organizers hope the project will spur regeneration around its facility. “First and foremost it will take 24 acres where there’s nothing happening and fill it with businesses that are already functioning,” Heine said. The site will be humming with activity. “We expect to have close to 250 employees showing up here every day, not including potentially volunteers or visitors.”

According to Seed Capital Kentucky:

The Louisville Food Hub has the potential to increase agricultural opportunities and revive our rural communities which are essential to the cultural and economic health of Kentucky. Food hubs provide the critical link to help bridge the gap by creating the infrastructure support to connect local people and businesses with local food. This infrastructure will, in turn, provide increased income and incentive to regional farmers to continue to grow food for the local markets. We believe that the Louisville Food Hub will improve our agricultural economy, public health, and the environment, and ultimately contribute to a more resilient local food economy.

The Food Hub will also bring programmed events and activities to Russell in a way that hasn’t happened in the past, Heine said. “It opens up opportunities for community events. Right now there’s not a lot of opportunity to have an outdoor concert in this part of town.” Among the events the hub anticipates hosting are farmers markets, community programs, educational outreach, performances, and more.

Additionally, the site will include upgraded bus stops with covered shelters. “Right now there aren’t any nice bus stops,” Heine said. “There’s a pole with a sign on it.”

Metro Louisville has also touted the plan as the realization of two key goals of its Vision Louisville program, which called for a food hub in West Louisville and building a waste to energy plant.

While fundraising is ongoing, the first phase of the project could break ground this year. Initial work includes building the biodigesters and clearing concrete from the site among other preparations. The hub could be open as soon as 2016. Funds are being sought from local foundations, government grants, donations, and New Market Tax Credits.

Hope springs eternal, but this OMA project seems almost as unlikely as the last proposed one proved to be…

I really hope this initiative becomes reality. Agribusiness in an urban setting is an unlikely, yet perfect fit for a city like Louisville. Wish I was there to contribute in some way.