Two Louisville sites are among 11 in Kentucky that have been newly listed on the National Register of Historic Places by the National Park Service. Both of Lousiville’s listings will help development projects in Schnitzelburg and Paristown Pointe move forward.

Among the benefits of listing a property on the Register is being able to apply for state and federal historic tax credits to develop a project, making the rehab of old buildings more affordable. Both Louisville structures will likely benefit from such incentives.

The two structures listed were the Klotz Confectionery Co., 731 Brent Street, and the Louisville Cotton Mills Administration Building, 1318 McHenry Street.

According to the Kentucky Heritage Council, the Commonwealth has the fourth highest number of National Register listings in the country, with more than 3,300 sites on “the nation’s official list of historic and archaeological resources deemed worthy of preservation.”

Klotz Confectionery Company

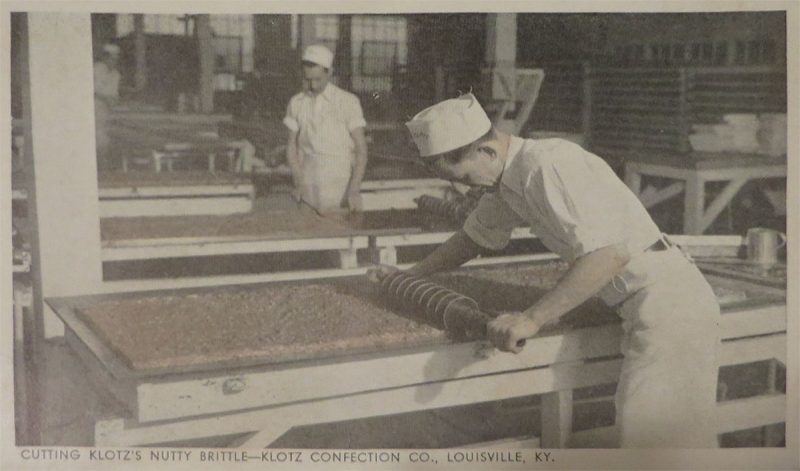

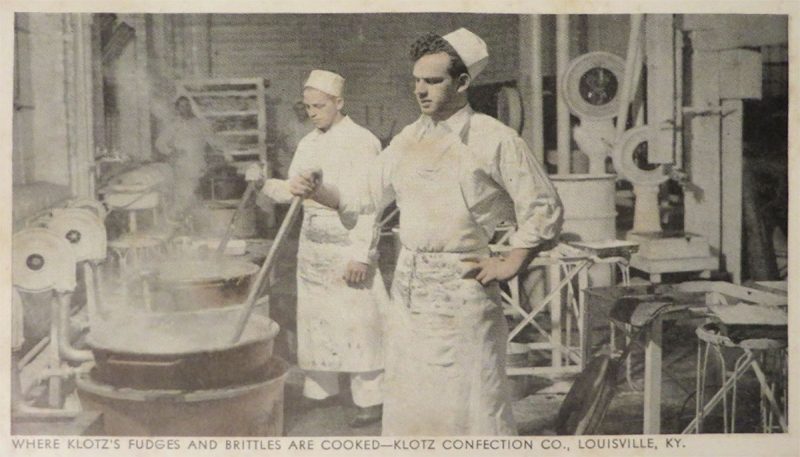

Klotz Confectionery Co. was built in 1937 in Louisville as a candy manufacturing plant, according to National Register documents authored by Joanne Weeter, a historic preservation consultant. Klotz’s opened in 1905 under Fred Klotz, and specialised in chocolate turtles, ice cream, and other candies. The company employed 92 people.

Charles F. Klotz, who had previously worked at Cuscaden’s Ice Cream, set out on his own under the banner of Klotz Ice Cream Works, originally locating at 519 East Market Street. “It was important for the Klotz company to illustrate to customers how up-to-date and sanitary their establishment was,” Weeter wrote, “as many producers and manufacturers of consumable goods at this time were under fire for unsanitary conditions.” Weeter’s research found that Klotz’s early operation could churn out 1,000 gallons of ice cream every day.

The company changed its name to the Klotz Confectionery Company in the summer of 1937 and moved its operation to Brent Street. Klotz purchased a two-story Brent Street property for $25,000 from leather processing company R. Mansfield and Sons Inc., but in August of that year, the structure was engulfed by a massive fire. By the end of the year, Klotz had rebuilt his facility and was again up and running making candy and ice cream.

In 1960, the company was purchased by Jeff H. Jaffe, “ending over 50 years of candy and confection production in Louisville, Kentucky,” Weeter wrote. Jaffe went on to be a successful businessman, buying companies in Brooklyn and distributing KitKat and Oh Henry candy bars, among other achievements. Charles Frederick Klotz, III, the last family descendent involved in the original Klotz operation, is retired and lives in Fisherville.

The two-story brick Klotz building is divided into six bays on its Brent Street facade with original metal-frame windows still intact. Inside, the structure features wooden columns, and Weeter speculates that, based on their age, they may have been salvaged from a neighboring Wirth, Lang & Company/The Louisville Leather Company Tannery Building.

The company closed in 1967 and Caron’s City Directory indicated it was then used by the Reynolds Aluminum Company. The structure was eventually folded into the Louisville Stoneware campus and is now part of a collaborative effort to rejuvenate the Brent Street corridor.

Once renovation is complete on the Klotz structure, it will become the showroom and factory for Louisville Stoneware. All work is expected to comply with the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation.

Louisville Cotton Mills Administration Building

Around the corner in Schnitzelburg, the Louisville Cotton Mills Administration Building was also listed on the National Register. Its listing is expected to help renovate the small outbuilding into a restaurant adjacent to the Germantown Mill Lofts. The larger mill property was listed on the National Register in 1982 (the Administration Building was not old enough at that time to qualify under the listing).

The mills expanded multiple times since it opened in the 1880s. The third wave of additions between 1910 and 1928 included a small office building built in 1910 north of the site of the present Administration Building. That structure was demolished sometime after 1941 after the new building was built to the south in 1936 (although the National Register documents also say the structure was built in 1941).

The single-story structure facing McHenry Street, built of brick and limestone, features Art Deco–style ornamentation and a symmetrical layout. The building is square in plan with chamfered corners. Above the inset front door is a stone relief of a worker using a spinning wheel and loom and “a castle turret wrapped with a banner with ‘Fincastle Fabrics’ printed onto it,” according to Joseph C. Pierson, of Pinion Advisors, who authored the Register listing.

Exterior windows and doors have been largely altered later in the building’s life, with only a few original windows existing around back. Smaller windows and doors on the front facade take away from the building’s grandeur, and new windows that fit the structure should go a long way toward improving its aesthetics.

Inside, a lobby features a reception desk with curved glass edges appearing much like the ticket booth to an old theater. A central open-plan office space fills the center of the building. It is lined with conference rooms and offices for executives.

Louisville Cotton Mills was the first cotton mill in Louisville, hitting its peak in 1948 when it was Kentucky’s largest textile mill, producing some 8,000 yards of fabric each day. The mill closed in September 1967. Most recently, the Administration Building had been used as a daycare.

The larger mill property has been converted into the Germantown Mill Lofts, with residents moving in this spring and summer. The Administration Building is planned to become Finn’s Southern Kitchen. According to an Insider Louisville report from last October, the restaurant will be operated by Steve Clements, former owner of Avalon and Clements Catering. A building permit was issued last November for the project and the restaurant’s website says it is expected to open in May 2016, two months later than its original projection.

Remaining Kentucky Listings

Here’s information on the remaining nine Kentucky listings, according to a press release from the Kentucky Heritage Council.

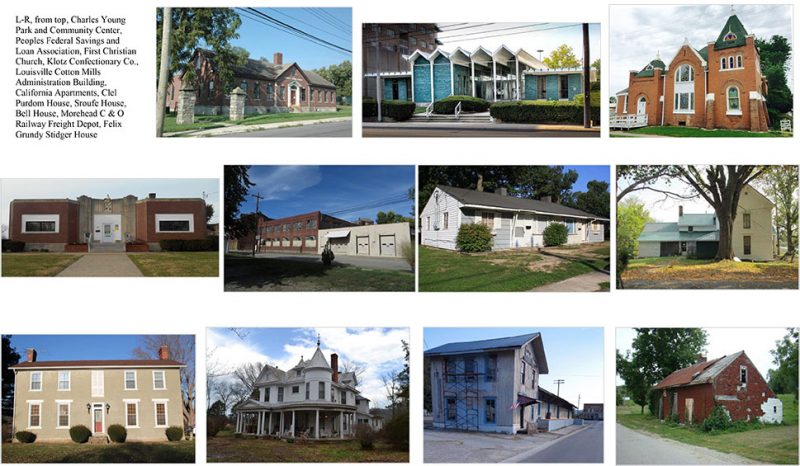

Charles Young Park and Community Center

540 E. Third St.

Lexington

Authored by Randy Shipp, historic preservation specialist with Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government.

According to the Kentucky Heritage Council:

Acquired in 1930, Charles Young Park was the second parcel of land purchased by the city to serve the recreational needs of the African American community. Its namesake, Col. Charles Young, was born into slavery in Mays Lick in 1864 and went on to become the third African American graduate of West Point, the first African American U.S. national park superintendent and the first African American to achieve the rank of colonel. According to the author, “In Kentucky towns, African Americans erected a community that stood alongside the community of whites, in which most of the same activities occurred…” The area listed is 2.6 acres, with two contributing buildings erected in the mid-1930s and one contributing site. These include the community center, a one-story, brick veneer, side-gable building on a raised, cut-stone foundation with a rear addition featuring a gymnasium and stage; and a one-story brick restroom. The remaining site consists of open green space, a paved, multi-use ball court and playground area. It was nominated under Criterion A, property associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our history, and Criterion C, embodying the distinctive characteristics of a type, period or method of construction. Its significance was evaluated within the historic context “African American Neighborhoods in Lexington, 1865-1965.”

Peoples Federal Savings and Loan Association

343 South Broadway

Lexington

Authored by Sarah Tate, historic preservation consultant.

According to the Kentucky Heritage Council:

Constructed in 1961-62, this iconic bank building was designed by Lexington architect Charles Bayless of the Firm Bayless Clotfelter & Associates. At the time of its construction, according to the author, the building “stood on the periphery of the historic downtown area of Lexington, a city which emerged in the early-19th century as a regional center of culture, agriculture, commerce and education.” The bank features a concrete foundation, concrete block walls with aqua-colored glazed brick veneer, and a precast “folded-plate” concrete roof. The building was nominated under Criterion C for its high artistic merit, and evaluated within the historic context “Mid-Century Modern Movement in Lexington, 1955-1965.” This building “provides a rare example… of a highly intact mid-century modern building with formal characteristics associated with several offshoots of the International Style,” the author writes. “In this nomination, the style is being defined as Neo Expressionism, and Streamline/Populuxe Modern.”

First Christian Church

201 North Washington Street

Clinton, Hickman County

Authored by Sarah Bowman, owner, and Marty Perry, KHC National Register Coordinator.

According to the Kentucky Heritage Council:

The church was nominated under Criterion C, embodying the distinctive characteristics of a type, period or method of construction, in this case Romanesque Revival. The church is constructed of brick and dates to 1899. According to the authors, “This building is the only instance of Romanesque style recorded in the county… Its masonry material, chunky proportions, and heaviness of detail impart a solidity to the building… [that] offers the local population a design that seemed sophisticated relative to others on the local landscape. For a church group intent on announcing the solidity, wealth and social prestige of their congregation, the Romanesque Revival design provided those messages.” The building’s significance was evaluated within the historic context “Romanesque Revival Buildings of the Jackson Purchase Region, 1875-1925.”

California Apartments

2900 Clay Street

Paducah

Authored by Melinda Winchester with Winchester Preservation

According to the Kentucky Heritage Council:

California Apartments is a private neighborhood made up of Gunnison Home duplexes on 5.58 acres. Constructed in 1952, the complex comprises 36 one-story duplex buildings and two vacant lots. It was designed by developers Omar Goetz, Prewitt Lackey and Heath Wells, who created New Home Constructors Inc. as approved builders through the Atomic Energy Commission. The project was financed by the Federal Housing Authority specifically for the workers of the Paducah Gaseous Diffusion Plant. The complex was nominated under Criterion A, determined significant within the historic context “Residential Housing Related to the Paducah Gaseous Diffusion Plant in Paducah, 1950 to 1955.” According to the author, all of the buildings display a uniformity of basic form and materials consistent with Gunnison Home Design Models. “All the units retain their identifying Gunnison features of the sheet metal chimney, metal shutters and metal flower boxes. The site plan has not been altered from its original configuration, and the sidewalks, interior courtyards and mature trees remain intact.”

Clel Purdom House

Lebanon vicinity, Marion County

Authored by Suzanne Coyle, Ph.D., owner.

According to the Kentucky Heritage Council:

Constructed in the Italianate style in approximately 1884, this two-story, frame house includes Italianate features such as overhanging eaves with decorative brackets and tall, narrow windows. The house is clad with weatherboards and sits on a stone foundation. The house was nominated under Criterion C and evaluated as significant within the historic context “Italianate Style in Marion County.” According to the author, “The development of Italianate architecture in the early 19th century flourished in urban areas where economic growth… was often reflected in the architectural design of the city. Small towns such as Lebanon, and rural areas of Marion County, might imitate those urban signs of economic prosperity, though at a later time than they first appeared in those cities. Use of the Italianate architecture then became a sign of economic status and cultural savvy in Marion County.”

Sroufe House

2471 Mary Ingles Highway

Dover, Mason County

Authored by Catherine Bache of Louisville

According to the Kentucky Heritage Council:

This listing includes a secondary brick building as well as the painted brick house, constructed in 1800, expanded during the antebellum period and again in 1975. According to the author, “The resource is being interpreted as a well-documented instance of a planned escape of three of the farm’s enslaved workers.” The property was listed under Criterion A, and the period of significance is a single year, 1864, during which a neighbor across the Ohio River, John P. Parker, assisted Celia Brooks, her husband and baby to escape from bondage under the owners of the house, Sebastian and Mary Ann Sroufe. The author cites a story from Parker’s autobiography that has also been well documented by others as verifying her argument for listing the site as significant within the historic context “Underground Railroad in the Borderlands of Kentucky and Ohio.” While Camp Nelson in Jessamine County is considered by NPS to be the first National Register listing in Kentucky associated with historic events related to the Underground Railroad, the Sroufe House is the first Kentucky residence to be listed for this association. According to the author, “Unlike the typical narrative of an Underground Railroad claim, part of the significance of the Sroufe House episode is that the story does not depict the Sroufe family as abolitionists or as sympathetic to the cause of liberating enslaved people. In this instance, the Sroufe House gained its association with the Underground Railroad in opposition to the owners’ interests.”

Bell House

7310 Columbia Road

Edmonton vicinity, Metcalfe County

Authored by Janie-Rice Brother, senior architectural historian with the Kentucky Archaeological Survey.

According to the Kentucky Heritage Council:

The Bell House was constructed between 1907 and 1909 for Curtis A. Bell and his wife, Cora, and designed by Albert Killian of Owensboro. A native of Adair County, Bell was a merchant and farmer and his wife was the daughter of a locally prominent merchant, farmer and lumber dealer, J.H. Kinnaird. According to the author, Kinnaird financed the building of the structure, a 2½-story frame house clad in clapboards with vertical wood siding and a distinctive two-story tower – a merging of Queen Anne and classical styles. The house was listed under Criterion C, evaluated within the historic context “Architecture in Metcalfe County, 1880-1910.” According to the author, “the house itself embodies the vernacular traditions persistent in Kentucky, where popular national styles remained relevant for years after they passed out of favor in more urban areas. But at the same time, the attention to detail, and the high style of finishes in the house set it apart from all other houses built in the same time period in the local architectural arena. The Bell House is significant locally as a rural architect-designed dwelling in the Free Classic style.”

Morehead C & O Railway Freight Depot

130 East First Street

Morehead, Rowan County

Authored by Gary D. Lewis, president of the Rowan County Historical Society.

According to the Kentucky Heritage Council:

Constructed in 1881 by the Elizabethtown, Lexington and Big Sandy Railway in Morehead, this depot was later acquired by the Chesapeake & Ohio (C & O) Railroad. According to the author, this stick, or Prairie-style frame building served as a passenger depot as well as a freight depot until about 1910 when a brick passenger depot was built nearby. Today the depot’s original wooden structure is intact and the building remains in its original location. According to the author, the depot “played an extremely significant role in local transportation, commerce, communications and social affairs of Morehead and Rowan County. This nomination acknowledges and relies on the tremendous transportation, economic and social changes brought about by the C & O Railroad in our area.” It was nominated under Criterion C as a type of construction and for a design that influenced future C & O Railroad depots, and evaluated within the historic context “Development of the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad in East Kentucky, 1870-1940.”

Felix Grundy Stidger House

102 Garrard Street

Taylorsville

Authored by Arnie Mueller, vice president of the Felix Grundy Stidger Historic Preservation Foundation.

According to the Kentucky Heritage Council:

The listing of this home in the National Register stands out in that the nomination was submitted under Criterion B, property associated with the lives of persons significant in our country’s past, a rarely used designation. Felix Grundy Stidger (1836-1908) was a spy for the Union Army during the Civil War, and the defined period of significance for the home’s listing, 1864-65, spans the two years he was actively engaged as a spy. Stidger traveled extensively during this time, and the covert nature of his work makes it hard to associate any other particular places with this role. The saddlebag-plan log house features a stone foundation, gable roof and central chimney. Today the building is in poor condition, yet because of its association with an important person, this did not preclude listing. The house was evaluated within the larger historic context “Spying in the U.S. Civil War, 1861-1865.” According to the author, approximately 390 known spies worked for both the North and the South throughout the war, including 43 women. Approximately 50 men and women on both sides were eventually executed, and some spies went on to successful careers, such as James A. Garfield, the 20th U.S. President. Following the war, Stidger relocated to Chicago, where he lived until his death.