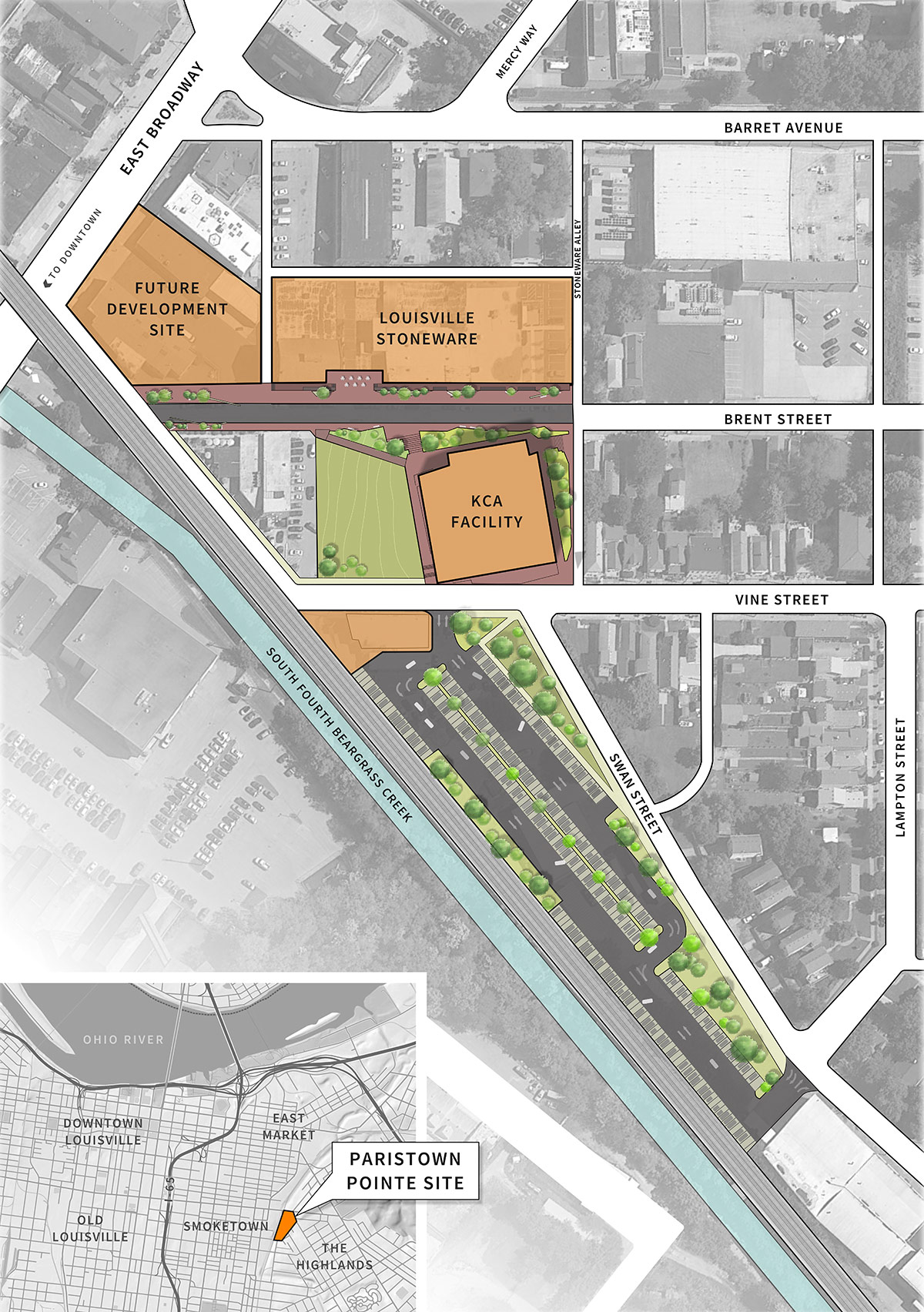

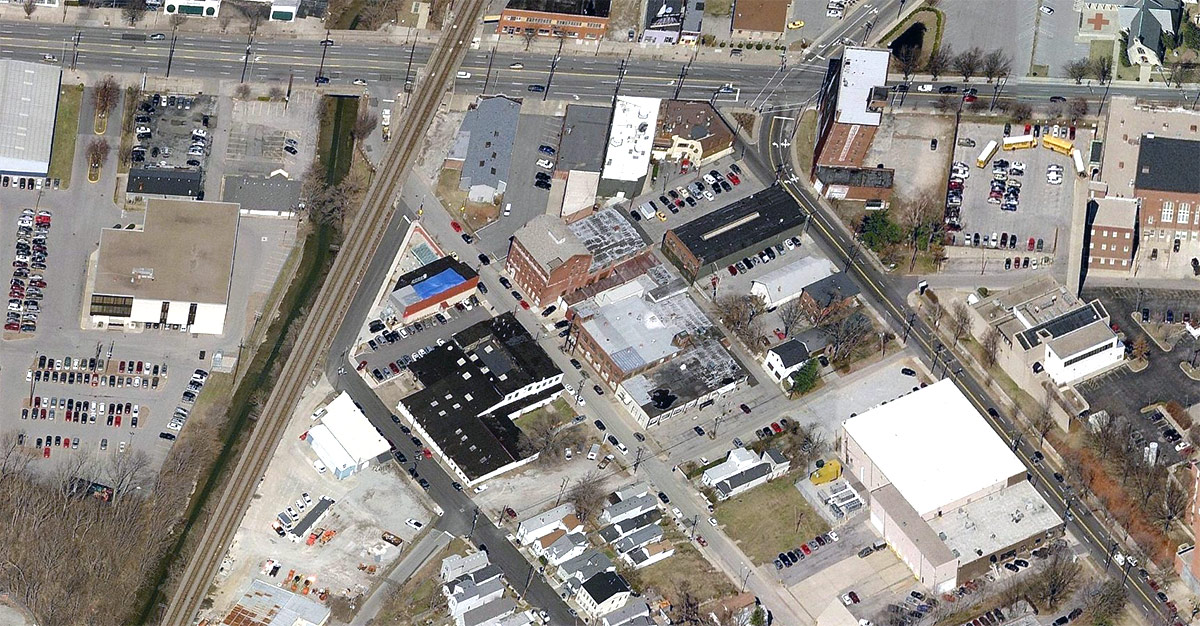

Paristown Pointe is not an easy neighborhood. The tiny wedge of land is hemmed in by a ’30s era elevated rail viaduct and Beargrass Creek on one side, steep terrain on another, and generally ignored along Barrett Avenue and Broadway.

“It is a joint, or a knuckle, between the Downtown grid and the grid that becomes the Highlands,” Charles Cash, principal at Urban 1 and former Louisville city planner, told Broken Sidewalk. “It’s really in a critical place to be a linkage between those two areas and really benefit both of them.” He said the gateway created by the elevated rail line gives the neighborhood a “hidden enclave” character. “It’s a natural gateway. It’s just enough off the beaten path to have a little bit of industrial mystery associated with it,” he said.

Historically, the area was settled by the city’s sparse French population in a tight-knit community centered around a Catholic church. Eventually, industry attracted to the creek moved in, including a large tannery that was active in the 1870s.

Paristown is also famous for another industry still active today—Louisville Stoneware—which has been active for the past 200 years at various sites around Downtown Louisville. And while the once-indispensable pottery is still popular, owner Steve Smith is planning for the next 200 years to make sure Louisville Stoneware remains an important part of the city’s heritage.

The plan for Paristown Pointe

That plan looks far beyond just Smith’s Stoneware business and aims to remake the entire neighborhood into a $28 million arts and culture district anchored by an expanded Stoneware factory, a theater for the Kentucky Center for Performing Arts, and a brewery and gastropub by Goodwood Brewing Company.

Two years ago, Smith enlisted Kulapat Yantrasast, principal of Los Angeles– and New York–based architecture firm wHY and a team of local designers including Kristin Booker of Booker Design Collaborative and Charles Cash of Urban 1 to plan a neighborhood renaissance under the banner of the Paristown Pointe Preservation Trust.

“Steve wanted to see something more come of the neighborhood,” Booker told Broken Sidewalk. Discussions about the neighborhood’s potential for development led to a design charrette that explored those ideas in more detail.

“All together a year ago, our team did a charrette with Louisville Stoneware to explore ideas,” Yantrasast told Broken Sidewalk. “Of course we focused on Stoneware, but the goal is the rejuvenation of an entire area—the Paristown neighborhood. With the master plan that we have, we can offer connections to the larger area.”

“The design charrette looked at opportunities of the existing buildings and worked within the confines of the neighborhood’s location, its hidden tucked-away nature, and thought about the kinds of uses that are compatible with that location and with each other,” Booker said. That charrette built off the work of a previous report on the area done in 2012 by the Urban Design Studio.

“We put together an idea and folks in the room loved it,” Booker said. “It helped solidify and resolve some concerns about parking availability, access to the site, how big of a building could fit on certain sites. We worked through a lot of programming and design questions that were unanswered until the charrette.”

Plan embraces Paristown’s industrial heritage

wHY, the same architect behind the Speed Art Museum addition, has since fleshed out the plans into a concise vision that’s simultaneously familiar and very new. The plan embraces Paristown’s industrial past with updated industrial uses. Stoneware is investing $6 million in its own facilities and Goodwood is putting up another $6 million for its operation.

The site’s complex existing infrastructure also inspired the design—including the creek and rail viaduct. “That’s what we like about the character of the neighborhood,” Yantrasast said. “This is really not going to be an architectural master plan that wants everything to be in order. All of the eccentric character of the area will be in play.”

A core of three anchor projects are linked by Brent Street to create a nexus of old and new. “The master plan doesn’t wipe everything out and put something new in,” Yantrasast said. “It’s really looking at the character and looking at how we can solve the problem while keeping all these eccentric levels and buildings on the site.”

The plan in detail

At Louisville Stoneware, historic buildings already listed on the National Register of Historic Places will undergo stabilization and modernization, including adding handicap access and following ADA codes.

Next, wHY is translating an industrial experience into the 21st century. “We really wanted to make it into a place that visitors can enjoy,” Yantrasast said. He reconfigured the factory layout to improve efficiency and make space for new community assets. “We moved some of the logistics of the factory to create places people can go to see how the stoneware is made.” A new café, restaurant, and a museum shop are planned. Flexible classrooms and craft shops will help Stoneware be an active part of the larger Louisville community.

Goodwood is also making a major investment that will announce the district to the high-traffic Broadway corridor. “The Goodwood brewery will be in the area between Broadway and Brent Street, very close to the train line,” Yantrasast said. The brewery and gastropub will occupy part of an old building and an adjacent parking lot. “There will be a real factory aspect to that area,” he added.

“Music is a big part of that area as well,” Yantrasast said, moving on to the Kentucky Center’s project. The 2,000 capacity, standing-room-only black box theater fills a void in the Center’s offerings and is expected to draw new artists to Louisville.

“It’s going to be a standing kind of venue with a main floor and a mezzanine and a multi-purpose stage,” Yantrasast explained. “You can do everything from a symphony orchestra to a rock band to a variety of other events there.”

The theater will be built across Brent Street from Louisville Stoneware on the site of a non-historic warehouse structure, directly south of The Cafe. Yantrasast said materials from that building would be salvaged and reused in the project. A parking garage is planned beneath the building.

Brent Street, the neighborhood’s spine, includes expanded public space around the theater, opening it up for outdoor events.

The sum is greater than the parts

Booker said each component of the master plan was designed to work together. “You almost never get a chance to design that way,” she said. “Here’s a brewery and restaurant facility, a hundred year old pottery company that’s going to completely revamp its facility with a historic renovation, and a ground up new performing arts venue all within a neighborhood that’s completely walkable in an area that’s been underutilized for years.”

Sustainable site planning

“We have a floodplain,” Booker said, “so we have to work with building elevations that rise above that floodplain. For existing buildings, we have to work within the parameters of how you adaptively reuse buildings in the floodplain.” Landscape architecture is helping to make this potentially devastating challenge into an asset.

Sustainable design helps mitigate those flooding issues, Booker explained. “We had to really look at green infrastructure and how we’re handling all of the stormwater,” she said. “Because we’re doing the three developments at the same time, we can think about those elements as a comprehensive system.”

Green infrastructure strategies include pervious paving in parking lots, below grade water detention and infiltration, and potentially bioswales. “We have a long, skinny property along Beargrass Creek, that is a perfect location for green infrastructure,” Booker added.

Paristown’s changing elevation also creates a resilient landscape. Booker compared the area to a bowl around Brent Street. “Everything rises up around it,” she said. “We have this series of stepping terraces that transition seamlessly from Broadway down to Brent Street.” She said the elevation there drops more than six feet, allowing space for a stepped beer garden. At the theater, berms define areas for outdoor performance.

Pedestrian-friendly design

“This is about creating a cohesive, indoor-outdoor environment,” Yantrasast said. “We wanted Brent Street to really be a pedestrian space.” He said public space materials are inspired by the existing buildings. “The skin of the building can be seen on the skin of the street,” he said.

Brent Street is designed to provide a pedestrian-first experience designed as a shared street. “We’re looking at a curb-less cross-section with different types of pavers to delineate sidewalks vs vehicular traffic,” Booker said. “We have plans and strategies for how different parts of Paristown can be closed down for music or performance events or markets.”

Paristown’s momentum is just the beginning

The team hopes the project can help to knit the neighborhood back into its larger surroundings.

“When we were working on the master plan, we even talked about having the possibility of having a bridge over Beargrass Creek,” he said. “Reconnecting, at least from a pedestrian standpoint if not a vehicular one, because on the other side of the creek is also an industrial area that’s sort of isolated and underutilized.”

Booker agreed. “Many people look at the creek as a huge asset and an opportunity for connections between neighborhoods,” Booker said. “That’s still a conversation that goes on. Ultimately, maybe they’ll raise the level of the creek on a consistent basis and you’ll be able to do some kayaking or canoeing.”

The three-part anchor unveiled today could also spur additional mixed-use development in the area. “The potential is there for the area to be a really interesting district,” Booker said. “We definitely see this as an arts and culture area, so the idea of providing reasonable places for artists to work and live is definitely at the forefront of the minds of the development partnership.”

And development is already beginning to pop up on all sides. To the north, a co-working space will eventually fill a long-abandoned church in Phoenix Hill and Nulu continues to thrive. West, Smoketown is experiencing growth with the rebuilt Sheppard Square and another venture to develop the Louisville Slugger block. To the east, hundreds of housing units are planned including 200 on the Mercy Academy site and up to 300 more at the old Phoenix Hill Tavern site.

Taking the project to the next level

wHY and the design team are working with Louisville’s K. Norman Berry Architects (KNBA) to flesh out the design documents for the Paristown Pointe district. KNBA is also working with wHY on the Speed Art Museum. But before the plan can move forward, the state needs to act.

To move the project forward the Trust is seeking tourism tax credits from the state. The Kentucky Tourism Development Finance Authority will review the project by the end of the year.

Y Louisville baby…… West of the Pointe is another super block of historic structures and a great potential filler site where the heat island mini mart sets ….. Y local is a much better bet than sleeping with out of towners and over paying for the Omni ……kudos to vision sustainability and green..

thanks for taking this story beyond the 4 same bullet points everyone got from the press release!

This is exactly the kind of project we should all be interested in attaining to preserve and progress Louisville.

Great investigative write-up, as usual.

what’s a charette

This seems like a great opportunity to ask Metro Govt. to publicly explain its apparent decision to abandon the Urban Government Center (on the eastern edge of Paristown). What are their plans? Has a cost/benefit analysis been done to evaluate the dollars that will be spent to move all these agencies to leased space vs. doing proper maintenance & repair to the Metro-owned government center? Seems like this needs a discussion all its own….

I dream of a day this site is easily accessible via the regional rail line that will run from St. Matthews to the Airport. Maybe one day…

Didn’t “Stoneware” drop ‘Louisville’ from their name a while back? (Separation anxiety?) Better get this project rolling before the city’s wrecking ball arrives. Won’t hold my breath waiting for the Interurban train to return. The Beargrass Creek bike path is long overdue.

The PPP Trust needs to correct the name of the creek which is a major feature of the area. South FORK, not South “Fourth.”

And clarify that Paristown is north of Breckinridge. The area between Kentucky St. on the south & Breckinridge St. on the north is part of Germantown.

For official neighborhood boundaries, check:

http://www.city-data.com/nbmaps/neigh-Louisville-Kentucky.html