[Editor’s Note: This article was originally published on the Sipp’n Corn blog on July 23, 2014. It appears here with permission of the author, Brian Haara. Follow SippnCorn on twitter @SippnCorn. We have added some new research and images to the end of the article.]

Just after the Civil War, at the intersection of the former Southall Street (later changed to Reservoir Avenue in 1884 and now Mellwood Avenue since 1895) and the Louisville & Shelbyville Turnpike (now Frankfort Avenue) in Louisville, two blocks from the where the Albert A. Stoll Firehouse (now The Silver Dollar) would be built decades later in 1890, the Mellwood Distillery was founded on the South Fork of Beargrass Creek. The distillery is reported to have been an impressive Richardsonian Romanesque building, but I could not find any pre-prohibition pictures through the University of Louisville online archives, and National Historic Registry documents for the Clifton Historic District did not include any photographs, either.

The Mellwood Distillery is historically significant because it filed one of the first lawsuits against a competitor who lied on its label about having a distillery (and who also tried to imitate the Mellwood brand).

As described in Mellwood Distilling Co. v. Harper, 167 F. 389 (W.D. Ark. 1908), the name “Mellwood” was actually an accident. It was founded by George W. Swearingen (circa 1837–1901), a Bullitt County farmer who, after graduating from Centre College in 1857, ran a small still on his family farm, which he called “Millwood.” After the Civil War, Swearingen moved to Louisville and opened a distillery, intending to name it “Millwood” after his old farm, on the border of what are now the Clifton and Butchertown neighborhoods. But when he ordered his brand, its name was misspelled as “Mellwood.” Swearingen decided to keep it anyway, and in 1895 this brand mistake found permanency when Reservoir Avenue was renamed Mellwood Avenue in honor of the Mellwood Distillery, which had grown to occupy both sides of the street for nearly an entire block.

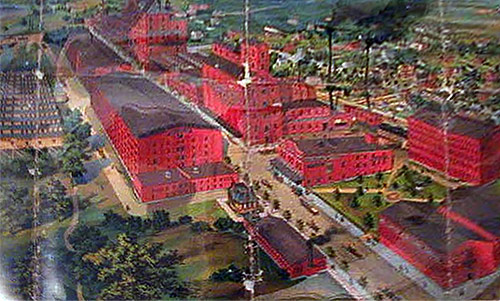

This 1884 map shows the expansion of the Mellwood Distillery across both sides of what was then Southall Street:

Swearingen sold his distillery in the late 1800s, and after he sold, it appears to have become part of the infamous Whiskey Trust (Kentucky Distilleries and Warehouse Company) in 1899. Having made his fortune, Swearingen stayed out of the distilling business, and focused instead on real estate (as president of the Kentucky Title Company) and banking (as founder of the Union National Bank).

As the Mellwood Distillery continued to experience great success, it attracted an imposter and led to one of the earliest court rulings on false labeling and fake distilleries. The imposter was the Harper-Reynolds Liquor Company, a distributor in Ft. Smith, Arkansas. Harper bought blended whiskey and bottled and labeled it as “Mill Wood,” used the name “Mill Wood Distilling Co.,” used a picture of an extensive distillery on the label, used “Kentucky” on the label, and included this description on its label:

This celebrated whiskey is made exclusively by the sour mash fire copper process, employed only in the distillation of the finest whiskeys, from carefully selected grain, and bottled only after being matured in barrels for 8 years.

The evidence, however, showed that there was no “Mill Wood Distilling Company” in Kentucky or elsewhere, that the whiskey was a blend, that it was not handmade, sour mash, or made by the fire copper process, that it was not made from the carefully selected grain, that it was not aged for 8 years, and that no such distillery existed as shown in the picture on the label. The court ruled that Harper used this false label “to mislead the public into the belief that in purchasing the ‘Mill Wood’ brand of whisky they were purchasing [Mellwood] whisky,” and it issued an injunction against Harper.

Unfortunately, the Mellwood Distillery was one of the many casualties of Prohibition. It closed in 1918, reopened after Repeal as General Distilling Company, and continued to produce the Mellwood brand, along with bulk whiskey sales. After General Distilling closed in the 1960s, the handful of buildings that survived through Prohibition seem to have been demolished in the 1960s and 1970s. It’s also a shame that there is no good photographic record of the distillery (although I’m continuing to look). This 1921 picture is described in the University of Louisville photographic archives merely as a stretch of Mellwood Avenue from Frankfort Avenue to Brownsboro Road, which is precisely the block where the Mellwood Distillery was located, so this must show the distillery property, albeit during Prohibition.

[beforeafter]

[/beforeafter]

[/beforeafter]

Historic view of Mellwood Avenue with a view of the street today. Besides losing the buildings, note the loss of street trees, the streetcar line, and even street lighting. (Courtesy UL Photographic Archives / Reference)

Additionally, this 1936 picture is described by the U of L archives simply as an “Alley between Mellwood & William,” without noting that it appears to also show the back side of the Mellwood Distillery (by then General Distilling) property:

Like the Mellwood Distillery itself, it also appears that part of the legal significance of Mellwood Distilling Co. v. Harper has been forgotten. Bottles today list fictitious distilleries by using assumed names, which is fine. But some brands pretend that they distilled the contents. The latest example might be Duke Bourbon, which claims on its label to be “Distilled By Duke Spirits, Lawrenceburg, Kentucky.” Duke Spirits claims on its Twitter profile to be “an artisan distiller crafting small batches of superior bourbon…” However, Duke Spirits is not located in Kentucky, it is not an assumed name of any Kentucky distillery, and the entity is not even registered to do business in Kentucky with the Secretary of State.

Other than coincidentally being in a few pictures, the Mellwood Distillery seems to have been lost to history. If consumers demand to know the source of their bourbon, Mellwood Distilling Co. v. Harper won’t be lost to history too.

[Editor’s Note: Below is a series of additional images that describe the old Mellwood Distillery’s urban form. By utilizing old maps and other available data, we created a rough massing reconstruction that shows how this complex created a distinctly urban street character along Mellwood and Frankfort avenues.

Also, it appears one small two-story brick building may have survived demolition as noted in the diagrams below. Finally, we have included views of today’s Distillery Commons at Lexington Road and Payne Street as an architectural comparison as to what these bourbon warehouses may have looked like.]

So glad to have you guys back- very refreshing!

Having Chet Zoellers book handy: So looking at the Sanborn’s I can’t help but notice on the 1905 map (3rd from top pictured above) that there are not one but two distilleries (by Registered Distillery No.’s) – the Mellwood Distillery (RD34) and Crystal Springs Distillery (RD12). Mellwood was founded by George W. Swearingen and Andrew Biggs in 1865. Swearingen was from Bullitt Co. and also had RD4 near Bowling Green called Spring Water Distillery and Biggs also operated RD297 Old Times Distillery (after a separation of some kind I assume). It says that the facility on Mellwood went though several phases. From what it looks like there was an initial set of buildings/still and a second set of buildings/still was added later. Contrary to what one would assume, RD34 was the first built and the north end of the site, while RD12 developed at the south end of the site in 1893 after a sale of the distillery. Swearingen sold to Rudolf Blake of Cincinnati and Jacob Schidlapp, and after that sale they replaced the original warehouse of the Mellwood distillery and likely built the Richardsonian Romanesque structure in 1893 – which was a six story building “constructed of brick, stone, steel and concrete with a slate roof;” Zoeller, 108). This seems to fit with the architectural tastes of the time. The distillery was very successful until prohibition and had the brands Mellwood, Dundee, G.W.S, Old Watermill, Normandy, Rubicon, Runny Meade, Montpelier Club, Old Water Mill and Marble Brook. Prohibition closed the facility and then it was renovated by Carl Nussbaum. It also appears that there were a few other brands “bottled” by the company, but not made there.

I also found it interesting that the pipe crossing Mellwood Ave. in the lead picture was actually transporting whiskey from the stills to the warehouses – which is pretty cool.

Thanks for the interesting piece of history. I currently own and operate a business in a building at 1430 Mellwood and I love to learn great history about the neighborhood. As a child I always wondered where the name Mellwood came from (Fischer’s Packing Co.), now I know it was a spelling mistake.

Thank you Broken Sidewalk.

Thanks for the article. As a boy (I’m 71 now) growing up on Story Ave, and later on Mellwood Ave I remember some of the buildings that were left. The article brought back some memories from that time. The warehouse that ran from Mellwood up Frankfort Ave was a place we walked past coming home from the Hill Top Theater (Conti’s now). The doors were often open in the summer and the coolness of the air and the beautiful aromas coming from those opening were something we always stopped and savored. It was not a smell like finished whiskey (which we probably wouldn’t have liked) just a sweet smell that defies description now. Each window had a thick metal door, and, when those doors were opened, had thick metal bars much like a jail.

The other warehouse I remember was on the north side of Mellwood between Brownsboro and Frankfort. There were spots behind that building where teenagers could hide to smoke (cigarettes were the vice of the 50s, nothing else).

Finally, just behind the “Slop for Sale” sign in the photo was a basketball goal with a metal backboard and a rim with no net where we neighborhood kids played. Not sure of its origin, maybe for the workers of some earlier time.

Anyway, thanks for the memories.

Thanks for the informative history. I recently discovered this sign which was the backing of photos of my father and his twin brother. Hidden for 60+ years. Being a fan of bourbon, I was interested in the history of this distillery. Anyway this hand painted sign is a great addition to my basement lounge. Thanks again.

I found a bottle of one of their whiskeys that was “for medicinal use only” under my grandmother’s sink unopened. Been having trouble trying to find out more about it.

I recently found this Melwood hand painted poster as a backer on my father‘s grade school photo. The size is 12 x 16“. I am a bourbon lover so you can imagine my surprise of this discovery. Quite the find!!

“Here’s a good drink”

Mellwood

D-4 .25c