“It’s hard to believe this was all just a pile of garbage at one point,” said Matthew Kuhl, senior project architect for Perkins + Will. “Right here, where we’re standing, there’s about 20 feet of fill dirt. But now, after more than forty years, this landfill has vegetation growing. There are trees.”

We were standing on the site of the proposed Waterfront Botanical Gardens on an unseasonably warm November day.

Botanica—an organization that has long been advocating for the creation of a botanical garden and conservatory in Louisville—chose Perkins + Will to develop a master plan for the proposed Gardens. In turn, Perkins + Will chose Louisville-native Matthew Kuhl to be the architectural project coordinator.

Walking along the picturesque 23-acre park site—bounded by River Road, Frankfort Avenue, Interstate 71, and Beargrass Creek—Kuhl took me on a guided tour through the soon-to-be Waterfront Botanical Gardens, our expedition starting at the top of the landfill plateau.

The Landfill Plateau

Kuhl remembers what he calls the “old days” of growing up in the Cherokee Triangle neighborhood. However, like many Louisvillians, Kuhl also remembers the old days of the Ohio Street City Dump.

After the historic flood of 1937, the Ohio Street City Dump was established to accommodate the remaining rubble and water-damaged buildings from around the city. According to Botanica, the landfill frequently caught fire and was left to smolder for days, burning away the contents of the dump and causing significant air pollution. Due to rat infestations, fighting these fires was difficult as the rodents would chew through fire hoses. It wasn’t until 1973, after the Edith Avenue Landfill opened, that city planners decided to cap the landfill with 25 feet of dirt before shutting it down.

“The fact that the ground beneath us that is still settling—that was one of the biggest challenges coming into this project,” said Kuhl.

Still, the team at Perkins+Will came up with a few solutions:

- Construct walkways with permeable pavers, made of either stone or bricks, which can move and adjust as the landfill settles.

- Use 30-plus-foot-deep, drilled shaft or pipe piles to serve as anchors, connecting structural foundations to the layer of bedrock beneath the landfill.

Many years ago, Jerry Abramson verbally designated the site for the purpose of a botanical garden. When Botanica entered into a Land Use Agreement with Louisville Metro Government to obtain the site, researchers conducted studies that showed that the soil and runoff from the site were safe.

However, the landfill posed a logistical challenge for visitors. As Kuhl pointed out during our trek, there exists a steep, 40-foot gradient between the top of the plateau and the street entrance along Frankfort Avenue.

As Kuhl said, “How do we move people from all the way down there – some of whom will be in wheelchairs—all the way to the gardens here at the top?”

The Entrance(s)

The site plan envisions two entrances in the middle of Frankfort Avenue, just south of the Heigold Facade. On the west side of the street will be the proposed parking lot entrance; on the other side, a steep and winding trail that will lead up to the entry plaza.

Kuhl explained that the winding trail would be built with the least possible incline, which ideally would be 1:20—one inch of rise to 20 inches in slope—in order to provide better access for strollers and wheelchairs.

“The first thing people are going to see is this, kind of, woodland trail leading up to a an entrance garden at the top,” Kuhl said, pointing toward a thicket of shrubbery in the distance.

“I’m not sure exactly what types of plants are going to be used—that’s something that Botanica will [ultimately] decide—but the layout of the gardens were designed to facilitate the growth and expansion of native vegetation,” said Kuhl, adding that the architects at Perkins + Will have recommended particular plant species according to the structural layout of the gardens.

Botanica researchers and landscape architects with Perkins + Will have conducted extensive plant surveys of the area to identify the existing natural assets of the site, which might suggest which plant varieties will be used in the gardens.

As visitors travel north, through the entry plaza and Visitors Center, they’re going to see the orchard and edible garden, which Kuhl speculates will have plums, peaches, apples, pears, and other staples that “kids are going to love and families will enjoy.”

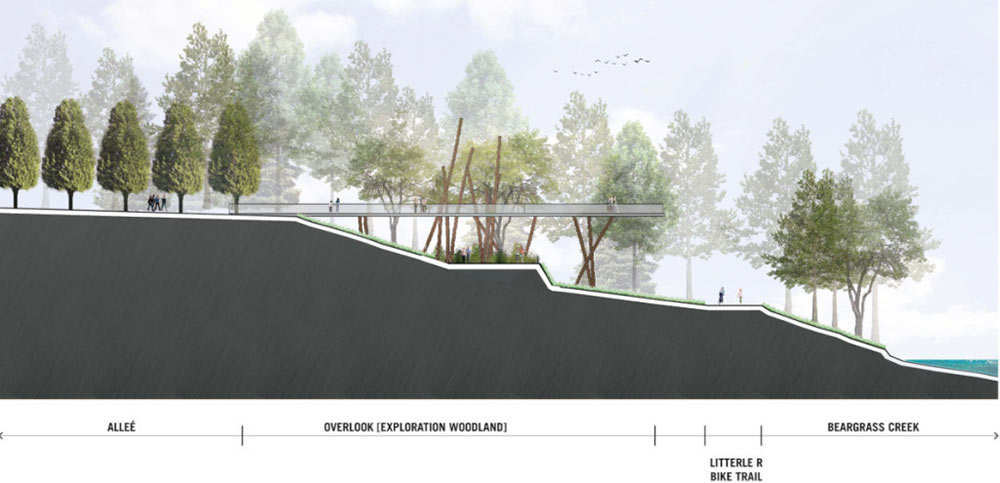

It is important to note that the site rendering only describes what the front entrance will look like. The site’s proximity to the Letterle Avenue Bike Trail along Beargrass Creek, however, provides visitors with a few alternate access points.

“Having the Letterle Bike Trail and Beargrass Creek right here has been a major asset to the design,” said Kuhl. “We haven’t gotten this stage yet, but we’d like to maybe have bike racks along the west side of the gardens and a trail expansion to connect the bike trail to the entry plaza at the front.”

The Central Spine

As we strolled across the meadow, Kuhl explained that the primary feature of the Botanical Gardens would be a central “spine” which will tie each individual garden together.

“Over there, the visitors center acts as the top of the spine,” said Kuhl, gesturing toward the top of the winding entrance trail. “Starting there, people can travel along the spine, through a planted trellis and other pathways, but it’ll stop right over at the east edge of the plateau. There’s going to be an overlook extending over the tree line, ending right at Beargrass Creek.”

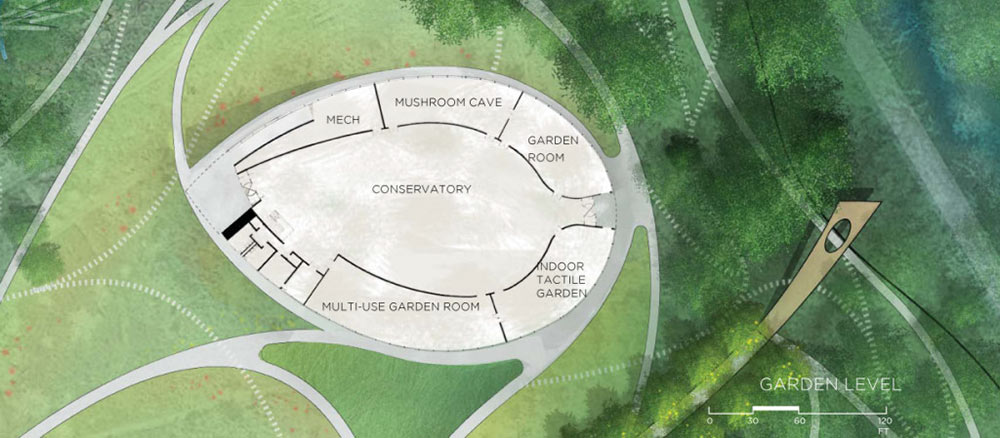

Following a the path laid out by the site plan, Kuhl also showed me the future location of the conservatory—situated between the Palisades and Japanese gardens to the north, and Gallery and Educational gardens to the south.

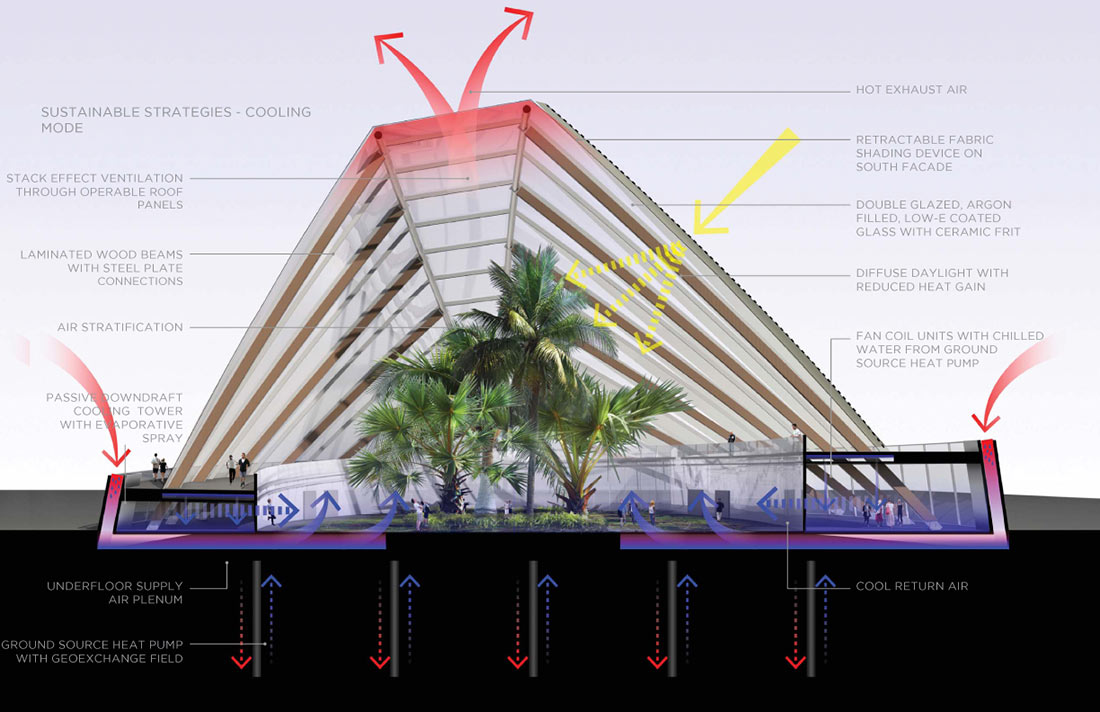

Both the visitors center and the conservatory are designed to be LEED Platinum certified. How does Kuhl hope to create such a building? A few ways…

- The Visitor’s center will feature a green roof, which will provide natural shade for visitors, but the grass on the roof will also be able to absorb rainwater that falls on the site.

- As the roofline gradually slopes down along the central spine, water will drain down the roof into a water filtration garden that encircles the visitors center – this feature will harness plants’ ability to clean the water as it passes from pool to pool.

- Conceptually, both buildings will be equipped with a ground source cooling/heating system that will minimize energy consumption and rely more on thermal heat from the sun during the winter months.

The purpose of the “spinal” design, according to Kuhl, is that it allows visitors direct access to various areas of the garden while also maximizing the site’s existing tree growth.

However, numerous evergreens will be added to the Gardens, especially along the southern edge of the site where it presses up against I-71. The evergreens, Kuhl said, will help create an acoustic and aesthetic buffer between the Gardens and the noise from the interstate.

The Future

Our trek came to a close, and Kuhl’s final remarks focused on the need for some kind of natural landscape within Louisville’s urban core. Kuhl said he believes the Gardens will work to connect people to their natural environmental, similar to Jefferson Memorial Forest, Bernheim Arboretum, and Yew Dell Botanical Gardens in Crestwood.

In order for the Waterfront Botanical Gardens to become reality, Botanica is hoping to raise approximately $35 million as part of its capital campaign.

According to Kasey Maier, director of program development at Botanica, the Botanical Gardens will offer memberships so local people can come to the gardens anytime they want. At this time, memberships cost $25 per person and $35 per family.

For more information, visit waterfrontgardens.org.

I hope to see this project become a reality, but I have some concerns about how realistic some of it is. Building on former dumps and landfills is a challenge. Will DWM allow drilled shafts or piers to be extended through the waste to bedrock? They may not since cap penetrations allow for additional infiltration and opens a pathway for groundwater contamination.

I appreciate the article, and the great press for Botanica and the WBG. This is a fantastic opportunity for Louisville and Southern Indiana, and the kind of project a designer dreams of having come along at least once in their career – and to have it come along in my hometown, makes it even more enjoyable.

However, I need to clarify a couple of things:

First – I am not THE architect who designed this project. I am one of many who helped bring this master plan to fruition, design the structures and coordinate with our Landscape Architects in developing the overall scheme that is now available to the public. I worked very closely with Ralph Johnson (the global design director of Perkins + Will), and Bryan Schabel, the Senior Designer, and numerous other architects to help manage and craft the very preliminary building designs shown.

Second – And most importantly – this is chiefly a Landscape and Urban Design Master Plan; a master plan that was driven and managed by Zan Stewart, my fellow Louisvillian and Landscape Architect. Zan couldn’t make the interview and walk through with BS that day, so I spoke about what I know best – the buildings. As a result, the article is architecture-centric. But I cannot stress enough how much this project is a result of Zan’s drive and determination to make this Master Plan a reality. His work and leadership are why the images you see in this article are stunning, and that upon completion – these gardens will be unparalleled.

Lastly, Louisville needs this project. If you want this to happen, it will need your support. Click the link at the end of the article and involve yourself in some way with Botanica and their vision to bring a Waterfront Botanical Garden to this community.