Louisville has pedaled ahead of the pack of cities vying for bike friendly recognition, advancing from Bronze to Silver in rankings from the League of American Bicyclists—and that’s a big deal. Bike Louisville, the city’s all-things-bike agency, has been pursuing the designation for several years, according to bike coordinator Rolf Eisinger, and a lot of hard work and leadership is finally paying off.

“This is a very big deal since we have been trying to reach Silver for several years, but we were lacking the funds to build bike quality bike infrastructure,” Eisinger said in an interview with the Bike League. “Then last year Mayor Greg Fischer’s administration invested $300,000 to build Louisville’s first urban bike network. This award will help validate that investment while providing support for an increase in funding in order to continue to expand the urban bike network.”

The competition

Landing in the Silver category pushes Louisville into a small group of cities making big strides in terms of bike safety. The Bronze entry level ranking includes 252 cities—Asheville, Baltimore, Charlotte, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Houston, Indianapolis, Nashville, Pittsburgh, Raleigh, and St. Louis among them—whereas only 73 cities across the country have achieved Silver status. The next step, Gold, includes 21 cities such as Madison, Wis., San Francisco, and Minneapolis while the top four cities in the country—Boulder, Col.; Davis, Cal.; Fort Collins, Col., and Portland, Ore.—hold Platinum rank.

Louisville’s new peers at the Silver level include Philadelphia, Sacramento, New York, New Orleans, Denver, Austin, Chicago, and Chattanooga.

“This increase in our bicycle friendliness rating is great news. It means we’re moving in the right direction in our efforts to build safer, more efficient connections across Louisville for pedestrians, bicyclists, and motorists,” Mayor Greg Fischer said in a statement. “Those connections make Louisville more livable for those already here and more attractive to those who might consider relocating here.”

Looking at Louisville’s success stories

But while achieving Silver status is great for the city, the hard numbers show there’s a long way to go before Louisville—and Kentucky—can call themselves truly bike friendly places. “It means we’re improving, we’re getting better. But it also means we’re not there yet,” Chris Glasser, president of Bicycling for Louisville, told the Bike League. “There’s a lot of room for growth. If you look at cities like Portland or Madison, you realize how much more can be done to make a city bike-friendly.”

Glasser told Broken Sidewalk that Louisville’s application for Silver stressed the successful completion of three major local initiatives. “We focused on the expanded network as our ‘most significant achievement,’ which we broke into individual success stories: the neighborways network; [buffered bike lanes on] Kentucky and Breckinridge streets (and overcoming the resulting bike-lash); and the opening of the Big Four Bridge,” he said.

Glasser told Broken Sidewalk that Louisville’s application for Silver stressed the successful completion of three major local initiatives. “We focused on the expanded network as our ‘most significant achievement,’ which we broke into individual success stories: the neighborways network; [buffered bike lanes on] Kentucky and Breckinridge streets (and overcoming the resulting bike-lash); and the opening of the Big Four Bridge,” he said.

Eisinger agreed that these projects have significantly helped the city’s bike friendliness. “Hands down the Big Four Bridge opening has been the biggest accomplishment,” he said. “Our Eco counter is counting over 500,000 pedestrians and bikes crossing annually.”

The numbers still need work

Despite these major gains, Louisville scored low on a number of key indicators, including “arterial streets with bike lanes” (zero percent vs. 45 percent Silver average), “total bicycle network mileage to total road network mileage” (9 percent vs. 30 percent Silver average), and “percentage of schools offering bicycle education” (17 percent vs. 43 percent Silver average).

A lot of these low numbers—especially for bike lanes on arterial streets—are more of a state problem than a local problem, and we already knows that Kentucky ranks second worst in the country for bike-friendliness. “Unfortunately, most of the major roads [in] Louisville are state roads, and our state-level transportation cabinet (KYTC) is somewhere between disinterested and antagonistic towards multi-modal design,” Glasser told the League. “Getting them to buy into creating bike-friendly designs is a big hurdle we’ve yet to clear.”

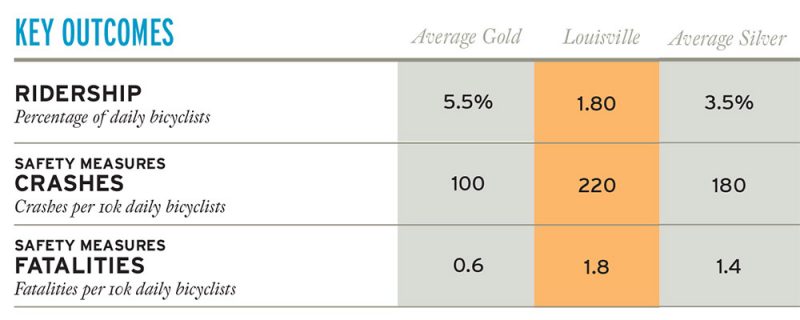

Meanwhile, Louisville also must work on improving its overall ridership and safety numbers. According to the League, only 1.8 percent of people in Louisville are daily bicyclists, compared to an average of 3.5 percent in other Silver cities. And let’s not even talk about Gold level cities, where on average 5.5 percent of people ride daily. Similarly, Louisville has a higher crash and fatality rate among cyclists than the average Silver city, and a significantly higher rate than Gold. Continuing to build out the city’s bike network will help bring Louisville in line with its Silver competitors, but that will take time and continued strong leadership.

A numbers game

One anomaly in Louisville’s score is that it uses a population of just over 250,000 to compute these figures. Glasser explained that the city’s application used the old city limits for data and geography, which can help or hurt the statistics on Louisville’s report card. He added that previous applications to the League had used data from the whole of Jefferson County. Looking only at the urban area helps to boost the city’s small-but-growing bike network mileage percentages but can skew other data compared to the overall city and region. If the city had applied using Metro data from the entire county, it’s unclear whether Louisville would have received the Silver ranking. “I wasn’t given any explanation from [the Bike League] about why we got the silver designation—just that we got it,” Glasser said, adding that he couldn’t say what prompted the League to overlook the city’s lackluster statistics to achieve Silver ranking.

Keeping up the momentum

In the end, however, Louisville pulled in the Silver ranking and we should be grateful for those like Eisinger and Glasser who are in the trenches fighting an often-uphill battle for bikeability in Louisville. We should use this as a time to reflect on what we’ve accomplished as a city—the three projects Glasser mentioned above are really big deals—and look at where we’re headed. Now equipped with these statistics and a report card, we can also more clearly look at where we stand compared to other cities, and Louisville will have to increase its momentum just to keep pace.

“I’m definitely aware of what’s happening in other Midwestern cities,” Glasser told the League. “Indianapolis has a great Cultural Trail. Cincinnati has built some protected bike lanes and invested in road diets on some of its major arterials. Those are great projects, and I’d love to see something comparable in Louisville. Right now, I think we’re a step or two behind in terms of building strong bike-friendly infrastructure, but I do think we have a Mayor for whom bike-friendliness is a big priority and a local culture that’s supportive. I’m optimistic we can catch up.”

Meanwhile, Louisville can also make quick improvements by adding certified Bike Friendly businesses. The city currently only has one—the Louisville Metro Development Center—but there are plenty more that could step up to the plate. Lexington, for example, already has four official bike friendly businesses. Promoting biking at the business level can help Louisville avoid kerfuffles like this one that the Louisville Bicycle Club pointed out on Facebook—the Kroger grocery in the Highlands blocked its bike rack to set up a BBQ stand. Simple considerations like these can help change the tone around biking in Louisville significantly.

The Bike League’s report card included the following seven steps to help Louisville make it to the next level:

- Dedicate more staff time to bicycle planning and programming.

- Continue to increase the amount of high-quality bicycle parking throughout the community.

- Adequately maintain your on-street bicycle infrastructure to ensure usability and safety. Increase the frequency of sweepings and address potholes and other hazards faster.

- Continue to expand and connect the bike network, especially along arterials and towards the suburbs. On roads where automobile speeds exceed 35 mph, it is recommended to provide protected bicycle infrastructure such as cycle tracks or protected bike lanes.

- Increase road safety for all users by reducing traffic speeds.

- Aggressively expand your public education campaign, promoting the Share the Road message. Ensure that the campaign message clearly conveys that both motorists and cyclists have the same rights and responsibilities on the road.

- Ensure that all police officers are initially and repeatedly educated on traffic law as it applies to bicyclists and motorists.

Taking the next steps for a bike friendly Louisville

Eisinger and Glasser aren’t resting on their new Silver laurels—they both have a lot planned moving forward.

“We are working hard to build out our urban bike network in preparation for a 2016 Bikeshare launch,” Eisinger told the League. “We have a few projects we have been working on which would provide separated bike lanes through the heart of downtown in both west and south directions.”

Glasser also listed what he’s excited to see take shape in the near future: “A two-way protected bike lane on Jefferson Street in downtown Louisville. That would be the first of its kind in the city, and it would go through the middle of the Central Business District of the city,” he said. “We also have a plan for a two-way protected bike lane on Lexington Road, which would connect into the Jefferson Street project to create a single four-mile cycletrack through city center.”

[Top image: A buffered bike lane along Fourth Street near the University of Louisville. Courtesy Bike Louisville.]

Thanks for the efforts already taking place….but, Louisvillians need to demand better bike infrastructure from our city and our state!! There’s so much more we could do.

It’s too bad that Louisville isn’t as progressive when it comes to making our city accessible for those with handicaps! Despite the fact that the ADA was passed in 1991 Louisville lags behind most other major cities in achieving accessibility for everyone. The worst part is they don’t seem to care nor address the issue in any way. Just drive down Bardstown Road for example and look at how many businesses there are not accessible.

The only way that Metro government will pursue making a business accessible is if you file a complaint through the human rights commission of Metro government! You then have to notarize your signature on the complaint form and jump through many other hoops before they will even investigate the issue. It’s certainly not a streamlined citizen friendly system and most people don’t bother with it because of its complexity in the amount of time and effort required. There is an even anybody in Metro government responsible for accessibility of public buildings except those owned by Metro government.

Trying to talk to somebody about the issue is fruitless to say the least.