The pattern of building more and more sprawl continues into the 21st century with potentially devastating economic implications to the well being of cities. Charles Marohn is a professional engineer in Minnesota who has been highlighting the problems with the way we design and build our cities today. To advocate for building prosperous cities, Marohn founded the nonprofit Strong Towns, with a mission “to support a model of development that allows America’s cities, towns, and neighborhoods to become financially strong and resilient.”

Marohn is the keynote at the Kentucky Heritage Council’s upcoming Strong Towns Conference, and we highly recommend attending. The two-day event takes place Thursday, September 24 and Friday, September 25 at the Kentucky Center for the Arts. Advance tickets cost $25 and tickets at the door are $35. The Heritage Council is partnering with Preservation Kentucky, Preservation Louisville, the Kentucky Main Street Program, and Friends of Kentucky Main Street. Additional support is provided by KHC member Nana Lampton and Hardscuffle Inc. To purchase advance tickets and view a conference schedule, click here.

Broken Sidewalk: How did the Strong Towns Conference begin?

Charles Marohn: We do these kinds of speaking engagements all over the country, but not at the level and intensity that we’re going to be doing this one. The Kentucky Heritage Council really invited us to come in and make a whole conference out of the material that we put together. We’ve done workshops around the country, but this is the first time we’ve been able to partner with a group like this and do a conference focused on Kentucky and its people.

It’s taking the dialogue on our conversations to the next level. Not only for people from Kentucky. There are people coming from all over the region and places all over the country.

I’m very excited. I have not been to Louisville for some 15 years. And I have to say as someone who is involved in this kind of work, I have heard a lot of good things about the city. I’m anxious to see what’s going on and I’m excited to meet people.

How do various issues such as preservation, land use, planning, and transportation come together and affect the built environment?

At the end of the day, what we focus on largely is the financial implications of our development pattern. Where all these things come together is really on the bottom line. Today in government we tend to organize ourselves by silo. You have engineers that do engineering work and planners that do planning work and historic preservation people that do historic preservation work. But at the end of the day, we are all kind of merging in the same place, which is, “how do we help our cities be financially strong and successful?”

When did you begin to see there was a problem with the status quo?

After I got out of engineering school I was ready to go build a great America. It was actually going out and working for an engineer for a number of years and seeing that even in places that were experiencing incredibly high rates of growth, that growth was not making us wealthy. It was not giving us prosperity.

I started asking some really hard questions. Why, even though we’re doing these projects and we’re creating jobs and economic development and all the things that these programs are set up for, are we’re not seeing the long term success? That got me asking questions about the money we spend, the money we get back, how the tax systems encourage certain types of investments and not others. And how our professions have all kind of all responded to a set of incentives that at the end of the day are very destructive to the bottom line of our cities.

Can you give me an example of how this works?

Yeah. It’s actually rather easy to understand and when you see it and grasp it, it’s like, “Oh, okay, never thought of that, but it’s way too obvious.”

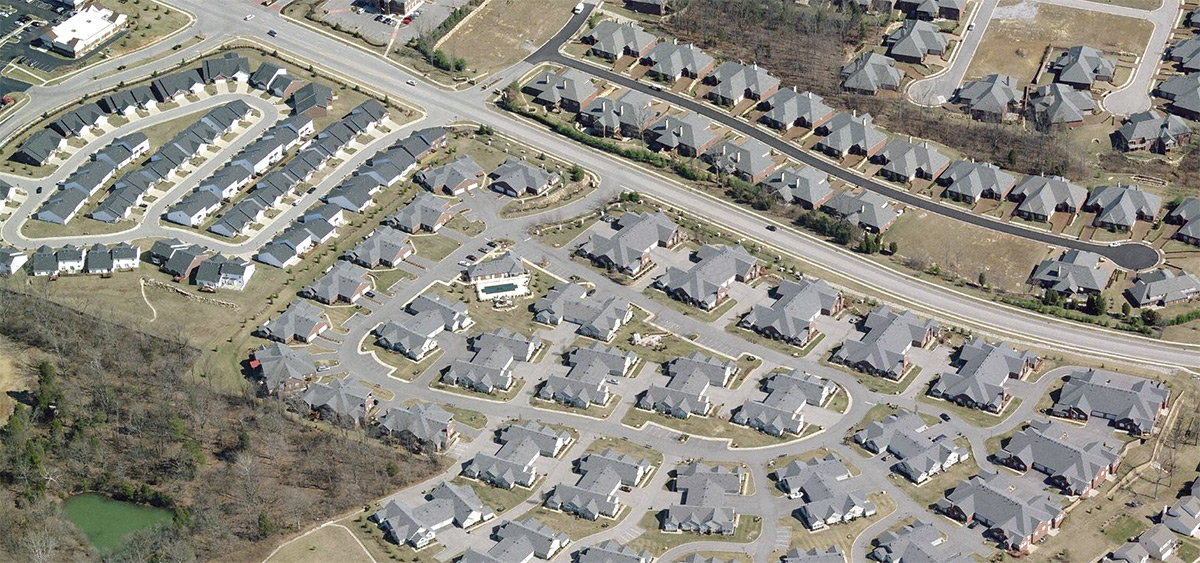

Most places when a developer comes to town and builds a new development, the town will ask the developer to put in the utilities—the roads and the streets and the sidewalks. Sometimes we get government grants to do these things. Sometimes we get other subsidies. But we have a growth model that’s based on building new stuff. And when we get that stuff, whether it’s through a developer or a grant or subsidy, someone else pays the cost of building it. The city, in exchange, agrees to maintain it.

From the city’s standpoint, we get new roads, we get a new pipe, we get a new pump. Whatever it is. At very low cost. And all we have to do is say, 20, 25, 30 years from now when it breaks, we’ll fix it. For the first 25 or 35 years, that’s a really good deal. You spend very little to get a whole bunch. The problem is that when you get out 25 or 30 years, what we see time and time again is that the amount of money that you brought in in that period of time does not come anywhere near covering the long term costs that you have.

Cities respond to this in one of two ways. They respond by saying, “well obviously what we need is more growth.” So they try to go out and get more growth doing the same thing, that essentially kicks the can down the road a ways, but makes your long term problem even worse. The other things cities do often is they take on debt. They try to make up for the fact that they’re short on cash and they don’t have enough wealth to maintain all the stuff they promised to maintain by taking on debt. And we see this over and over and over where cities do everything they can to ramp up growth and wind up taking on enormous amounts of debt. And when they finally come to the point where they can’t continue that approach, they’re saddled with enormous debts and very few options.

Is that what you’ve described as the Ponzi scheme of development? Where you have to build more to pay for what you’ve already built?

Yes, we call it the Growth Ponzi Scheme. Cities get trapped in this where they’re encouraged to pursue growth as a way to solve their near-term problems and all they do is take on larger long-term problems in the process.

It seems despite a growing interest in building in the city, suburban growth won’t let up. How does the city keep pace? How do you change the pattern? Do you change the law, work with developers?

The answer is all of the above. I think especially in the planning profession we’ve suffered for a long time from thinking there’s an answer—that there are one or two policies we could do to fix this. What we’ve recognized at Strong Towns is that we’ve got a whole system that’s pushing in one direction and we actually need to get that system pushing in an entirely different direction.

So depending on the group that I’m addressing, there’s things for everybody to do. We need people to start talking about growth and development differently. We need politicians to stop subsidizing really bad development and stop taking on liabilities for future generations that they have no chance of meeting. We need engineers to change road and street standards. We need planners to develop new codes. We need banks and financial institutions to develop new products that will allow different styles of development to be financed. So there are a ton of things to do. I think the most critical thing is to understand what’s going on and then be able to rationally develop some responses to that.

What do we do with the existing network of sprawl that’s already been built?

Well, I’m going to paraphrase the Iowa department of transportation director, Paul Trombino, who said in June when I was there doing a lecture with him a lot of this stuff is just going to go away. We don’t have the money to maintain it. We don’t have the money to fix it. And it’s just not going to be maintained. It’s not going to be there. I think once you understand that in reality, that we’ve literally built more than we can possibly pay to fix, it opens up a whole other realm of thinking.

I think we need to start talking about how do we transition into a world where these things, from a market standpoint, start to go away. What we see now in a macro sense is an increase in suburban poverty and an increase in social isolation that goes along with that.

When we walked away from inner cities in the 1950s and ‘60s, we left behind the poorest people who couldn’t leave. But we left them behind in places that were largely coherent. You could walk to the store, you could walk to a job. You could take a bus to an employment opportunity. When we leave those same people behind in the suburbs, or when we isolate them the way we are trending right now to do, we’re not leaving them in a coherent place where they have a lot of options.

My biggest fear right now is that in this contraction that’s mathematically destined to happen—if you can’t maintain something you won’t—is what happens to us socially as these places become more and more desperate? I think that’s an open question. I don’t necessarily have an answer for that except to say that I think very few people are aware of it. If more people were aware of it then we could devote some mental energy to figuring out how to deal with it.