[Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by PeopleForBikes’ Green Lane Project, a program that helps U.S. cities build better bike lanes to create low-stress streets. It appears here with permission.]

As hard as we try to avoid doing so, humans tend to base racial assumptions around our personal experiences.

This can sometimes lead us to odd conclusions. As Homer Simpson once put it: “white people have names like Lenny, whereas black people have names like Carl.”

This shows up everywhere in American life, including bicycling policy. One big reason we created a new report about race, ethnicity, class and protected bike lanes was to help more people (including us) think more clearly about the actual differences between Americans of different backgrounds when it comes to biking. In addition to interviewing and profiling experts and advocates around the country, we gathered statistics and studies that helped us understand how these issues intersect with good street design. Here are 12 of the most interesting stats in the report.

1) People of color are leading the U.S. biking boom

Last year, we showed how bicycling has continued to grow among young adults, but not nearly as fast as it’s been soaring among older adults. There’s a similar story in our racial and ethnic backgrounds: bicycling has become a more important travel activity for white Americans, but not nearly as fast as it has among Americans of color.

In part, this is because people of color were harder-hit by the Great Recession, which caused all racial groups to scale back expensive car trips even as the number of inexpensive bike trips increased. Which is, if you think about it, sort of the point.

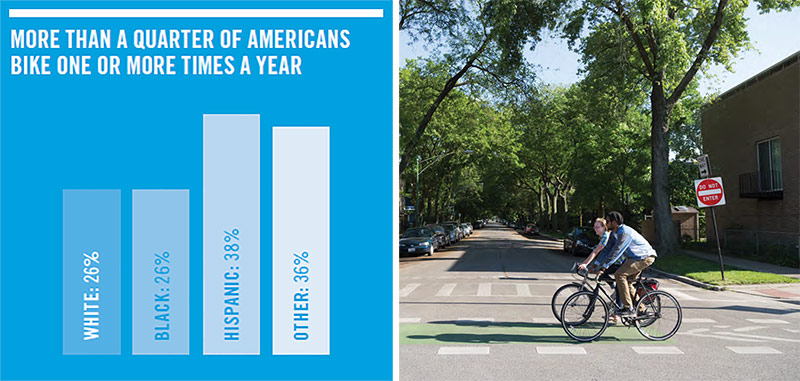

2) People of color are more likely to ride bicycles

All told, 34 percent of Americans aged 3 and up ride a bicycle at least once a year for one reason or another. That number would be lower if only white Americans and African-Americans were counted. But people of Hispanic backgrounds and others (Asian, Native, Pacific Islander and more) bike quite a bit more.

A note of caution: the survey used in this question and the next few was conducted only in English, which (according to the U.S. Census) only two-thirds of self-described Hispanic or Latino people speak “very well.” However, there’s no particular reason to suspect that biking rates among Hispanic people would give dramatically different answers based on which languages they speak the most.

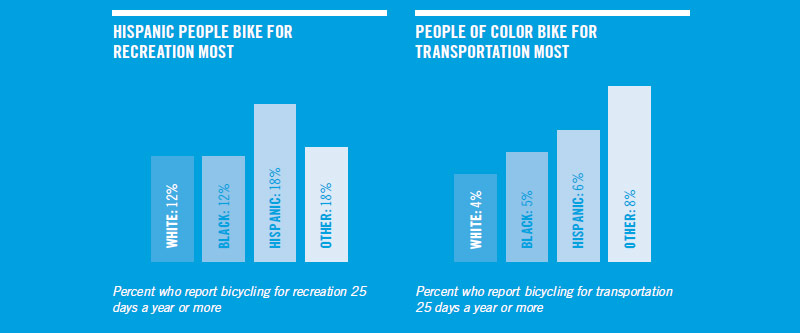

3) People of color are more likely to be regular riders

These figures look at people who get on a bike on a truly regular basis—at least a couple times a month on average, or on a weekly basis during summer and fall. Other than Hispanic Americans’ tendency to ride recreationally more often, there’s not a lot of variation in the sort of bicycling Americans tend to do the most: riding for fun. But the rates of riding to get around vary quite a bit.

4) People of color are most likely to want to bike more than they currently do

Most Americans would like to bike more than they do. But for whatever reason, that’s slightly more so among Americans of color (and yes, these differences are statistically significant). Related: Americans of color, especially Black Americans, are a bit more likely to see bicycles as a convenient mode of transport.

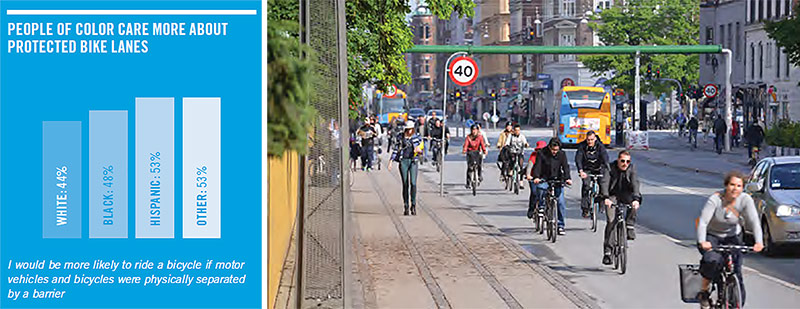

5) People of color are most likely to say protected bike lanes would affect their riding habits

This is another statistic where the variation isn’t huge; many Americans report that physical barriers between bikes and cars would make them likelier to ride. This makes sense, since physical barriers are standard in the cities where bicycling has become a regular activity for a third of the population or more: Copenhagen, Rotterdam, Hangzhou. But interestingly, the Americans most likely to predict that barriers would matter to them are people of color.

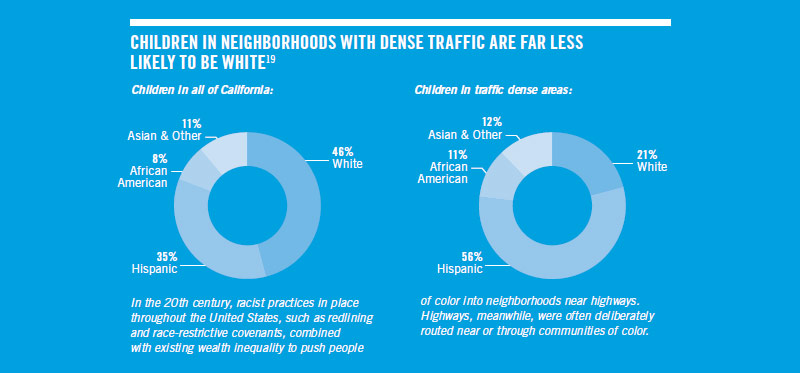

6) Clean air is a social justice issue

Unfortunately, part of the reason Americans of color say they’d respond more strongly to protected bike lanes may be that they’re more likely to live in neighborhoods with dense or heavy auto traffic. This has many other effects, including air quality. These numbers from California show the dramatic disparities.

7) Professional planners are disproportionately white

Though the urban planning profession is more multicultural than it once was, that’s a sadly low bar. These figures from American Planning Association members show one of the big challenges cities face in distributing resources equitably: almost all of the people whose job it is to convene interest groups and gather community needs and feedback come from a single racial background.

This makes it harder for cities to figure out what their residents want and need, and can contribute to unequal distributions of infrastructure and other resources.

8) No U.S. ethnic group has more at stake in improving bike safety than Latinos

This is probably in part because Latinos are so likely to spend time on a bicycle; see above. But more car-oriented streets in Latino neighborhoods (again, see above) and disturbing patterns in the ways people treat vulnerable road users of color may also be at work here. Whatever the reason, this is a disparity no one wants to see.

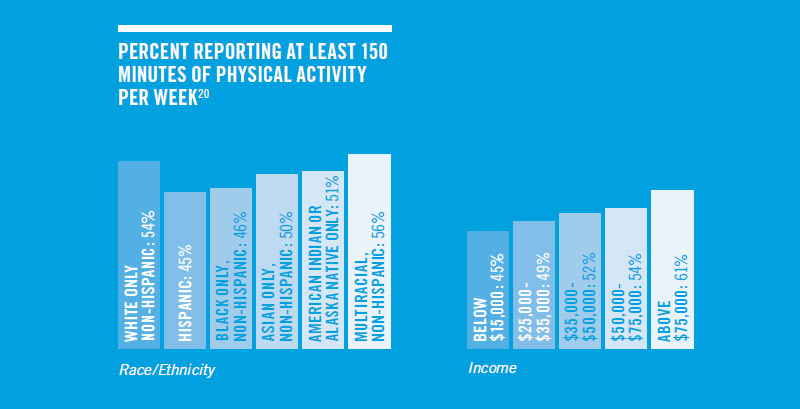

9) Access to physical activity is a social justice issue

Everyone needs some exercise to feel healthy and be healthy. That doesn’t have to happen on a bike, of course—but biking is a terrific way to get it into your routine, especially for those of us pressed for time. This federal study found big differences by race, ethnicity and income: most memorably, that the poorer you are, the less likely you are to get a decent 20 minutes or so of physical activity per day.

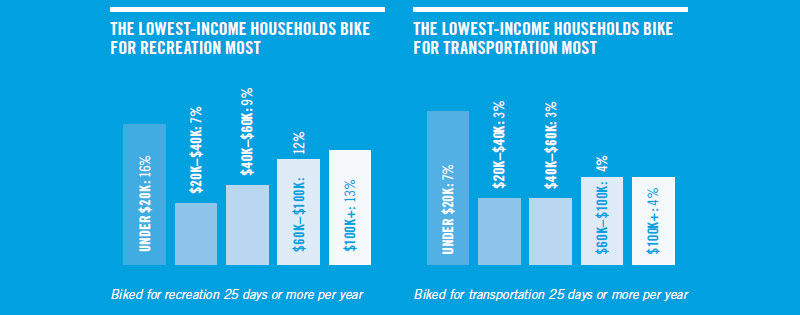

10) The lowest-income households bike far more, for recreation as well as transportation

Ethnicity and income are different issues, of course, but because income disparities in the United States are so deep, they’re related. The last three facts have to do with income alone.

It might be no surprise that Americans who make less than $20,000 a year are twice as likely to bike for transportation as other Americans. But what’s less discussed is the fact that bicycling is an important way for lots of low-income Americans to have fun. At an estimated 10 cents per mile, it sure beats the multiplex on price.

It’s interesting that outside that lowest-income group, bicycling is more common for wealthier households, especially for recreation. One thing to keep in mind: generally speaking, wealthier households simply do more things for fun. People earning $20,000 to $40,000 aren’t in poverty, but they’re probably not flush. People working multiple part-time jobs or raising kids on single incomes don’t have time for much of anything beyond bare essentials.

11) The poorer you are, the more likely you are to commute by bike

What if we set aside recreational trips and lunch runs and look only at the longest trip most adults take each day: the journey to work? Bike commuting is very income diverse—more so than walking, riding transit or driving to work—but it’s clearly most important to the lowest-income workers.

12) The lower your income, the less you drive

This should probably be obvious. But in recent years, as more poor families have been priced out of some central cities, an inaccurate idea has spread that driving is more important to poor people than it is to rich people, and that making it faster or more convenient to drive or park a car is a way of helping low-income people.

The opposite is true. Though most Americans drive regularly, wealthy Americans drive far more.

The fact that suburban poverty is on the rise isn’t likely to change that, or at least not much; cars remain expensive. What if instead of pretending that suburban poverty is somehow making driving egalitarian, we worked to make car ownership more optional in our suburbs? Because of the way suburbs are built, bicycles are an ideal tool for suburban transportation. And after all, most Americans want to bike more than they do. Pretty sure we read that somewhere.

Interested in these issues? Check out People for Bikes’ new report, Building Equity: Race, Ethnicity, Class and Protected Bike Lanes. It combines these statistics with stories and insights from people of color around the country working to use protected bike lanes to improve their communities.

For the sake of consistency in challenging assumptions, People for Bikes and the Alliance for Biking and Walking should now publish their organizational demographics as a companion to the report along with a demographic survey of bicycling enthusiasts/advocates in general.

Provocative, Josh! Thanks.