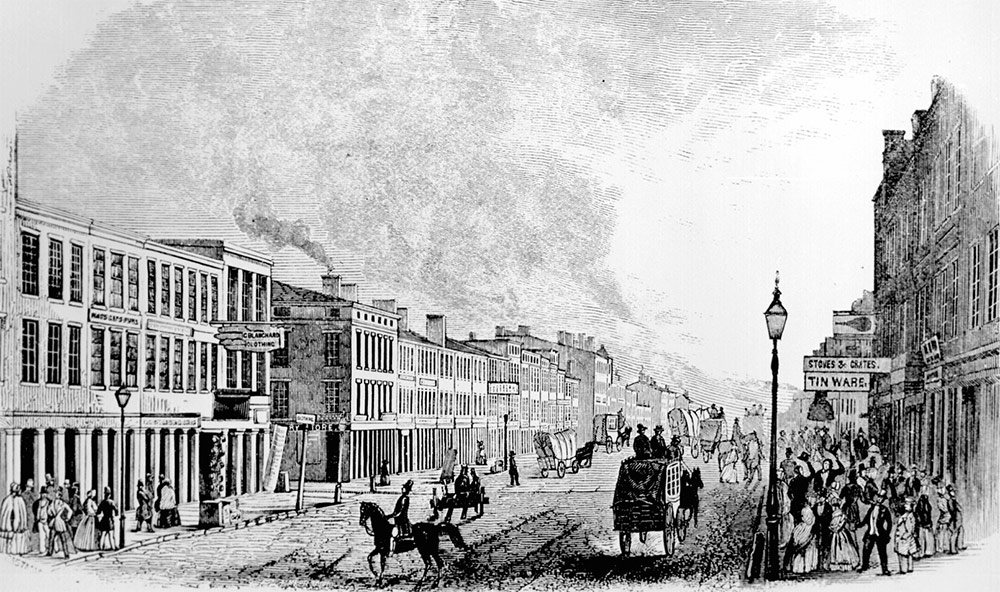

We’re all familiar with Fort Nelson Park in Downtown Louisville at West Main Street and Seventh Street. It’s a manicured pocket park in the heart of Downtown Louisville‘s cast-iron district. But what used to be there before the park? Another beautiful cast-iron warehouse, of course. At the time, these buildings were considered utilitarian industrial structures, but we know today that these once-workaday warehouses are vital to the success of Louisville with their historic beauty and flexibility for new uses.

Tiny Fort Nelson Park actually housed three distinct buildings, each standing 5-stories tall for a total of 58 feet up from the sidewalk—that means whopping 16- to 20-foot-tall ceiling heights. Two of the easternmost buildings were standard three-bay cast-iron and brick buildings with limestone facades. They appeared very similar to each other in design, but slight detail differences at the windows and on the cast-iron columns show that they were, in fact, distinct structures. On the west, a slender single-bay structure attached to the middle building, lending it a grander entrance. The structures likely dated to the 1860s, putting them at a similar age as neighboring buildings.

The eastern-most structure once was a wholesale liquor warehouse—meaning it was chock full of bourbon—and the remaining western structures were part of a larger harness and saddle factory that comprised what is today the Harbison Condominiums at 711 West Main Street. That building, renovated in 1986, includes retail on the ground floor with 20 condos above.

A photograph of the site in 1907, which we’ve stitched over top of the modern day view, shows the structures firmly anchoring the corner. A hand-painted sign above one of the doors shows part of the building operated as a Levy Clothing store while the other portion continued to operate as Harbison and Gathright Wholesale Saddlery. A horse-drawn wagon carries bundles of tobacco—called hogsheads—farther west on Main Street to a series of storage and auction warehouses.

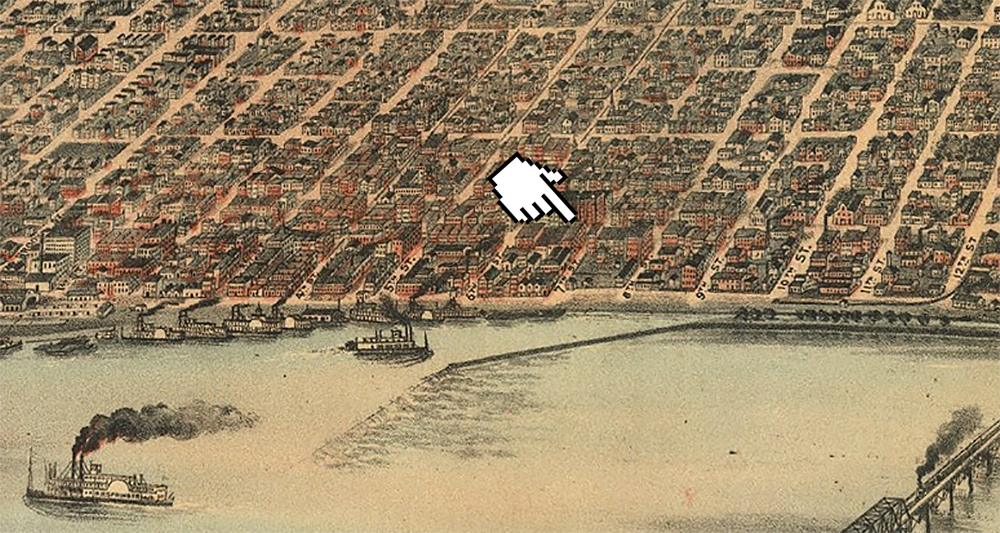

The buildings were torn down in the 1960s, perhaps at the time of construction of the floodwall that runs through the site—maps from the late 1950s that predate the floodwall show the buildings standing while photos from the 1970s show a derelict West Main Street with the buildings gone. The site was ideally located at the time directly south of Louisville’s other great train station—called Seventh Street Depot, Central Station, and Union Station at various points—which carried passenger and freight traffic on elevated trestles along the Ohio River roughly in line with the elevated Interstate 64 today.

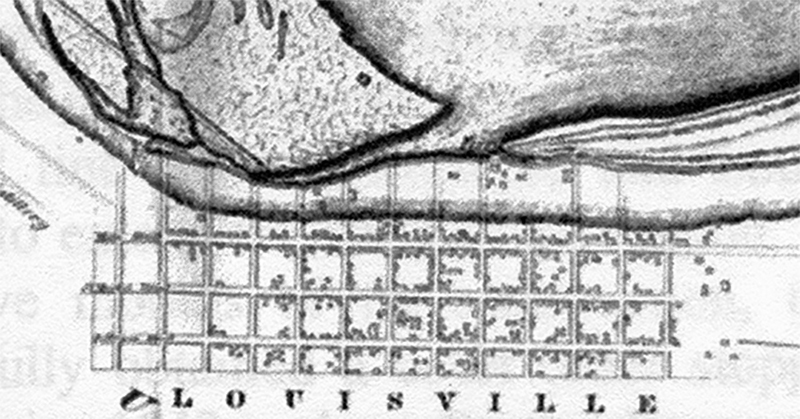

Decades before the warehouses were built at Seventh and Main streets, however, the site housed Fort Nelson, which was completed in 1781 by Richard Chenoweth. The wood-and-earth-reinforced walled city protected early settlers—just a handful back then—from Native American and British attacks in the Revolutionary War period. It was named after Virginia Governor Thomas Nelson, Jr., as Kentucky had not yet become its own state. At the time, what was inside those walls was essentially Louisville, while the outside was the wild western frontier.

According to the Encyclopedia of Louisville:

The fort was built north of present day Main Street between Seventh and Eighth streets. Construction was probably begun by [George Rogers] Clark’s troops under the command of George Slaughter late in 1780 and completed by March 1781… Fort Nelson was an impressive structure that covered an acre. It was surrounded by a ditch with spikes in the bottom. The dirt from the ditch was used to help strengthen the outer walls of the fort, which were supposedly capable of resisting cannon fire.

Fort Nelson was called the strongest fort in the West besides Fort Pitt [in Pittsburgh], and its strength undoubtedly discouraged attack. Ironically, the fort was built late in the Revolutionary War when the need for it had almost disappeared. By the late 1780s there were reports that the fort had been abandoned and was in poor condition.

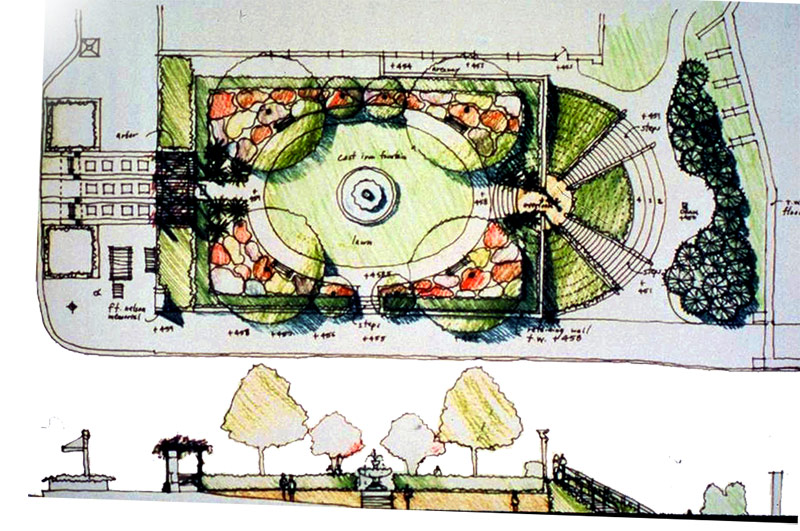

In 1991, landscape and urban design firm EDAW (now part of architecture and engineering giant AECOM) was commissioned by the Louisville Development Authority to design a streetscape along West Main Street that responded to the area’s unique history and cast-iron architecture, according to EDAW’s Dennis Carmichael.

In 1997, the streetscape design won an Honor Award in Urban Design from the Potomac / Maryland Chapter of the American Society of Landscape Architects and later in 2008, the project also helped West Main Street receive distinction as one of America’s ten great streets from the American Planning Association.

Part of that streetscape project included a $350,000 pocket park replacing an earlier 1960s park rumored to have been designed by the successor firms of Frederick Law Olmsted. According to Charles Cash, who served as the city’s project manager during EDAW’s renovation, the old Fort Nelson park included a freeform design with a sloping, winding path lined with benches.

The old Colonial Dames monument—a rough-hewn stone obelisk created in 1912—was placed haphazardly inside the old park. Its ornate plaque reads, “To commemorate the establishment of the town of Louisville, 1780. On this site stood Fort Nelson, built 1782 under the direction of George Rogers Clark after the expedition which gave to the country the Great Northwest.” That monument now stands prominently at the corner, providing an anchor to the corner of the park and giving it a stronger urban presence.

The new Fort Nelson Park, designed as a formal Victorian sitting park to respond to the age of the surrounding buildings, incorporated remnants of demolished cast iron buildings to form gateways into the park. While these cast iron pieces look similar to those of the buildings that once occupied the site, they appear different in design and were likely taken from other unfortunate demolitions in the area.

If the long and storied history of the Fort Nelson Park site weren’t enough, EDAW’s park design brought another layer of history to the block. According to Carmichael, “Ft. Nelson Park is a pocket park at Seventh and Main that epitomizes the qualities of a nineteenth century Victorian garden, complete with a cast iron fountain salvaged from the Louisville World’s Exposition.”

That fountain has had quite its own history over the years, as well. The cast-iron fountain was forged in the 1870s for a sprawling estate south of the city built by Reverend Stuart Robinson, and later occupied by the DuPonts. In 1883, the land was developed into the Southern Exposition, where fountains anchored four corners of the Victorian world’s fair. After the fair, the Exposition grounds became St. James Court and Central Park.

Later, two of the fountains were relocated to the old courthouse, now Metro Hall, on Jefferson Street. A 1925 photograph of the courthouse (above) shows the fountain on the corner of Jefferson Street and Sixth Street. At some point in the 20th century, the county decided to remove the fountains entirely from the courthouse and one was lost to the scrap yard, according to Charles Cash. He told Broken Sidewalk the other was rescued by Carol Swanson, who displayed the fountain in her garden on Upper River Road, where it resided until being relocated once again to Fort Nelson Park in the early 90s. “The city restored it as the centerpiece of the garden,” Cash said. “The cast-iron fountain fit well with the cast-iron district.”

In October 2014, however, the Victorian fountain was removed and replaced with a small Japanese maple. The shrub was named after the founder of Republic Bank, Bernard Trager, which funded the planting and maintenance to the park. The switch made few waves in the press at the time, and Mayor Fischer noted the event on Twitter, “Thanks to the Trager Family and RepublicBank for the investment in improving Ft Nelson Park at 7th and Main.”

Given its historic significance, the fountain’s removal was a major concern, but it appears that the change is only temporary. According to Jessica Wethington, spokesperson for Metro Louisville, “the fountain is currently stored safely at Seventh Street and Industry Road until repairs can be made.” No information on what those repairs entail and a timetable for restoring the fountain were available and a call for further information to the city’s Director of Facilities, Cathy Duncan, was not immediately returned.

While we’re happy to hear the park’s historic centerpiece is slated for repairs, the overall future of Fort Nelson Park remains uncertain as development proposals for the awkward site to its north come and go. The site, which we mentioned once contained Central Station, has been host to many failed development proposals over the years, including a tower by I.M. Pei for Vencor corporation, the notorious Museum Plaza tower by OMA and then REX, and a number of other tower ideas.

Museum Plaza had planned to wipe out the existing Fort Nelson Park to form an entry plaza to the ill-fated skyscraper. The first design by Rotterdam and New York City–based landscape architecture firm West 8 called for a scene out of the Pacific Northwest with large redwood trees, a waterfall cascading over massive boulders, and meandering stepped paths.

West 8 was eventually let go from the project and kinetic artist Ned Kahn was brought on to re-imagine the entry park and larger plaza above. Working with San Francisco–based RHAA Landscape Architects, Kahn proposed removing all the trees entirely, replacing them with a cascading sheet of water. A spiraling ramp hovered over top of the water and encircled two “vortex fountains.”

Those plans are long gone, but with the city’s interest in redeveloping the Museum Plaza site, the future of today’s Fort Nelson Park appears to be in some jeopardy. The floodwall to the north remains a major access obstacle to the riverfront development site and whatever eventually gets built there will likely include a redesigned park entrance. Whatever its future holds, we hope the park’s design remains sympathetic to the long and complex history on the site, the architecture of West Main Street, and the monuments and fountains that make the space unique to Louisville.

[Images: UL Photo Archives Reference One, Two; Chris B / Flickr.]

Thank you for this very informative article. I have walked through this park on several occasions but was not aware of its historical significance. My hope is that it remains preserved for future generations.

The fountain was nice, but I’m certainly not heartbroken to see it go. The improvements at Fort Nelson (i.e. new landscaping, fresh coat of paint, removal of fountain) in 2014 were very needed. Fort Nelson Park used to be a major breeding ground for mosquitos. Instead of enjoying your lunch in the quaint park, you were lunch. And, more times than I would prefer, I have seen homeless men peeing or giving themselves some self-lovin’ (if you know what I mean) in the bushes against adjoining building. The large shrubs were removed in the remodel and replaced with smaller plants. Now, one would have to be quite the exhibitionist to engage in those activities! The park is certainly a gem downtown and across from 21c, and you can wait there for the Main/Market electric bus circulator! In my opinion, one of the nicest TARC stops in Louisville!

I liked this story I was researching this because my Grandfather fought with General Clark back in 1780 to 1783 there at Fort Nelson. I am intending to visit there someday.

When looking north while standing in the park you see the flood wall. I propose there be a painting on the floodwall of what Fort Nelson looked like. Maybe even the sketch itself!

The fountain was just sitting on the sidewalk in front of the police substation at 7th and Industry as of 2022.