Last week we revealed a fright of building ghosts distributed throughout the city, their disembodied pieces piled among weeds atop landfills or stacked behind rusting cars at impound lots—or simply vanished. The oldest of these cases dated back to 1975 when the exuberantly ornate Board of Trade building on the corner of Third Street and West Main Street was torn down for a street widening project. We counted some nine building facades or pieces that were allegedly put in storage for later reuse, all of which have been sitting for a decade or more. And pending a Landmarks case, the old Louisville Water Company Headquarters on Third Street might join them in this architectural limbo.

But half a century before the Board of Trade was boxed up, another facade was being put in storage just two blocks away. In 1921 the second of three Galt House hotels built in Louisville was being torn down on the corner of First Street and Main Street to make way for a new warehouse for the growing Belknap Hardware & Manufacturing Company.

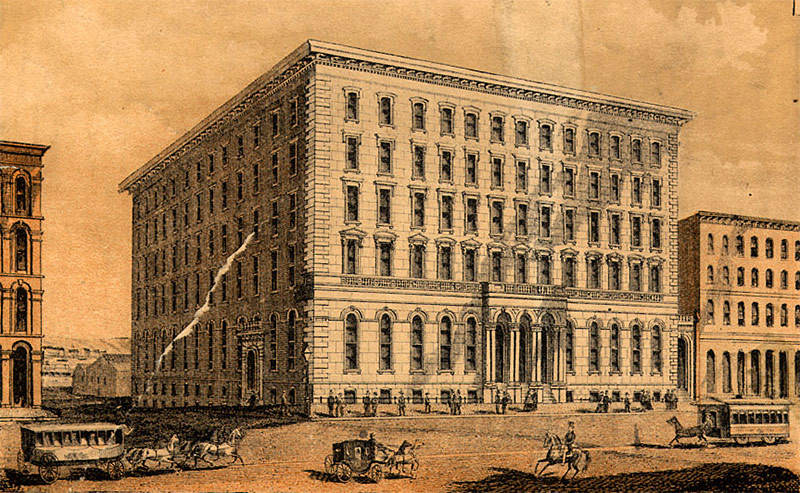

Today that demolition would have caused community uproar, and for good reason. The second Galt House was designed by noted architect Henry Whitestone and opened in 1869, four years after the first Galt House burned to the ground a block away at Second Street. It was one of the finest and most historic structures ever built in Louisville.

But in the early 20th century, newer hotels like the Seelbach (the Brown wouldn’t open for another couple years after the Galt House’s demolition) and the glamour of Fourth Street were stealing business away from the city’s once bustling waterfront. The Galt House, host to presidents and celebrities, was struggling in the 20th century, eventually closing up entirely in 1919. The hotel that cost $1.1 million to build in 1869 had sold in 1909 to a new owner for a mere $80,000. Even then it couldn’t stay afloat.

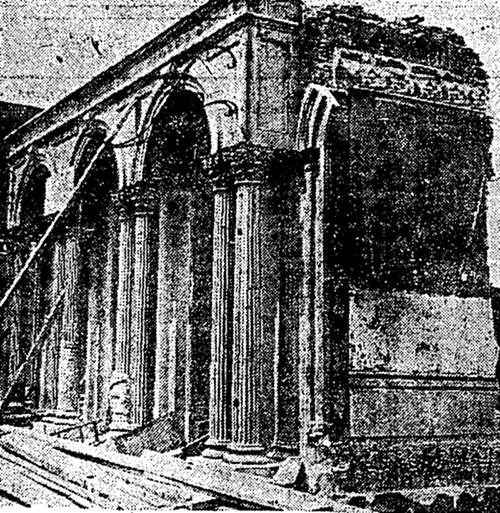

According to reports at the time, a portion of the Galt House facade was saved. An ornate arched portico once formed the grand entrance to the hotel off Main Street. Adorned with three overscaled archways and eight Corinthian columns, the architectural element would no doubt have been an imposing monument.

According to a Courier-Journal article dated January 9, 1920:

When the Galt House is torn down to make way for the new warehouse of the Belknap Hardware & Manufacturing Company, it is possible that the front portico, a beautifully constructed bit of architecture and a reminder of historic occasions, will be saved as a relic and placed in one of the parks of the city.

The suggestion was made by Mrs. Grace C. Robinson, a Louisville expat living in Santa Barbara, California. Among her ideas was moving the portico to Cherokee Park as an architectural “relic.”

She encourages the city not to “neglect an opportunity to preserve one of the chief landmarks of historic times” rather than it “be allowed to go to the scrap heap with the remainder of the building.” Belknap company president William Heyburn agreed and called on the community to find a use for the stone pieces.

“As a matter of fact,” Mr. Heyburn told the Courier-Journal, “the Galt House has many pleasant personal associations in my memory, and I would be inclined to share with others a sort of sentimental attachment to it. I lived in the Galt House for five years in my bachelor days, moving out of it twenty-nine years ago this January. I would be glad to have the portico saved.”

The following year, a new use appeared to be at hand. In another Courier-Journal article dated August 24, 1921, the portico would be saved and used as a memorial to the late Alvin T. Hert, who had died a few months prior.

A committee of Hert’s friends led by a D.G.B. Rose purchased the columns at auction for $500 and were in the process of seeking out a location to rebuild them, including sites in Cherokee Park and other city parks.

That fall, the columns were the last piece of the building remaining, and the article solemnly noted, “With the removal of the columns, the old Galt House will have vanished.”

But who was Alvin T. Hert?

Alvin Tobias Hert was born on April 8, 1865 in Owensburg, Indiana. He served as warden of the Indiana Reformatory in Jeffersonville in from 1895 to 1902, and later moved to Louisville where he founded and became president of the American Creosoting Company, which made treated railroad ties. The company’s offices were located in the city’s first skyscraper, the Columbia Building, 401 West Main Street (ironically torn down for an expansion of the modern Galt House complex.)

This last venture brought Mr. Hert great fortune and in 1915 he bought the sprawling 1,300-acre Lynnford estate (aka Lyndon Hall) on Hurstbourne Farms, a mid-19th century Gothic Revival manor, and enlarged the house. Hert’s main residence was located at 1349 South Third Street in Old Louisville, a block from Central Park.

Mr. Hert died suddenly of apoplexy June 7, 1921 in Washington, D.C. while attending the Republican National Convention as a delegate from Kentucky. He was likely under a great deal of stress as his company was in the midst of a major Interstate Commerce Commission dispute. Nonetheless, Hert was a political bigwig. Among those in attendance at his funeral on his Hurstbourne estate were cabinet secretaries under President Warren Harding, the Governor of Kentucky, the former Governor of Illinois, and other prominent Republican political figures, according to his obituary in the New York Times. He is buried in Cave Hill Cemetery.

After his death, his wife Sally Aley Hert took over the company and the estate and was active in politics. She expanded the house in 1928 with help from architect E.T. Hutchings. After her death in 1948, the Hurstbourne estate was sold and later became the sprawling subdivision along Shelbyville Road. His home still serves as the clubhouse for the Hurstbourne Country Club.

(View the Hert estate in 1932 here, its garage, and servants’ quarters.)

In the end, Mr. Hert was given a memorial bridge instead of a memorial portico. The Alvin T. Hert Memorial Bridge opened in 1923 spanning Beargrass Creek in Cherokee Park. The stone balusters and other details bear a striking resemblance to those that once adorned the old Galt House and its grand portico, but are not the same.

An inscription in the bridge reads, “In memory of Alvin T. Hert, a progressive citizen whose character was reflected in his service to his friends and to his country.”

In 2006 a car crash knocked a portion of the bridge into the creek and vandals completed the job. For two years the bridge remained in disrepair, but was rebuilt in 2008 at a cost of around $300,000.

The mystery around the old Galt House portico remains, however, and it’s unclear what ever happened to the building pieces. Could they still be in storage somewhere in a pile of weeds? Were they incorporated into another project around town? Did they end up in the scrap heap with the rest of the Galt House? If you have any information on the history of the portico, please share in the comments below.

[Editor’s Note: Special thanks to a tipster for sharing the origins of this story and helping with research.]

Henry Whitestone never could catch a break. That ugly surface parking lot at Sixth and Main was also a Whitestone. And gorgeous to boot. So I guess this tells us all how much credibility to place in reconstructed facades……..

The Hert Bridge has been repaired but it no longer looks like the picture you have posted. The weeds are over grown…..all over the park. Right now they are dying due to lack of rain but the weeds have been allowed to grow and block the views that Olmstead built into the parks. Debris from the creeks over flooding are gathering behind the bridges and soon I am sure that will destroy a few of them. Belknap Bridge can no longer be seen from the small parking lot. I have pics of before and after of many of the areas of the park. I have been going there since the 60’s. I have left my views on the Metro Parks FB page and sent them private messages, they are so innocent…blaming it on the rain, it was like that before the rain. Now to the old buildings, every time they destroy one they are destroying our history, ignoring our present and there will be nothing left for the future. It makes me sick every time one is destroyed. There is not reason on some of these other than the almighty buck. You don’t see Savannah, NOLA or many other cities doing this. The monstrosity they want to put where the Water Co is located is sinful. Omni in other cities has built hotels that is in the same genre as the buildings around it. There is not reason they could no incorporate this building into a new one and mimicking the design.

The Highbaugh family owned the estate Hert estate in the 1940s and 1950s. They sold it and it became Hurstbourne Country Club. The mansion became the clubhouse.

I believe part of the portico is displayed behind Humana on 1st and Main street…looks very similar!

@Stephanie: That’s actually from an enormous warehouse that Humana tore down in the ’90s. They’re the old stone doorways to the building. Check it out here: http://brokensidewalk.com/2010/lost-louisville-belknap-warehouses/