[Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by PeopleForBikes’ Green Lane Project, a program that helps U.S. cities build better bike lanes to create low-stress streets. It appears here with permission.]

For 10 years, urban policymakers have been talking more and more about the so-called “interested but concerned”—people who would like to bike more but who are, for some reason, held back.

Make biking attractive to those people, the thinking goes, and great things can happen to a city: road capacity rises, parking shortages ease, auto dependence declines, development costs fall, public health improves.

Since then, several local studies have explored the opinions of these people, usually within cities that were already fairly bike-friendly. But since the “interested but concerned” concept was popularized, there’s never been a study of these people at the national level.

Until now, that is.

A new national survey interviewed 9,376 adults who want to bike more

As part of its new national survey about bicycling participation, PeopleForBikes hired a public research firm to anonymously ask thousands of U.S. adults a series of questions. One of them: whether they would like to ride a bicycle more often.

To make sure people weren’t lying to make us happy, we asked whether they’d ever visited an imaginary website, and then disregarded all answers from people who claimed they had. After that, to ensure a representative sample, we weighted the remaining answers by age, gender, region, ethnicity, and income to make the sample look like the United States.

As we shared here last week, 53 percent of American adults answered that yes, they want to bike more.

But that question also gave us an opportunity to do something else: to look more closely at the situations of the people who answered “yes” to this question. By comparing their answers to different questions, we can explore one of the holy grails of bicycling advocacy: what the most important obstacles to biking might be.

After a week of looking closely at the numbers, here are our six most interesting discoveries.

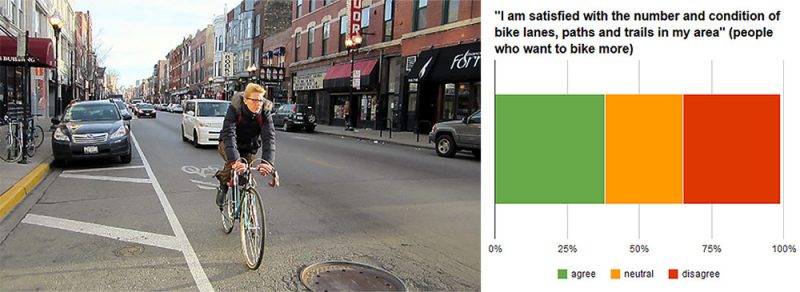

1) One third of people who want to bike more are dissatisfied with existing bike infrastructure

Among people who would like to ride more, 34 percent disagree with the statement below, 26 percent are neutral and 38 percent agree.

This is actually slightly better than the population at large (31 percent of all adults agree with the statement), which probably reflects the fact that people who like to bike tend to live in bike-friendlier areas. But it still leaves a huge share of adults who disagree—and speaks to the fact that in the United States, we simply haven’t built enough bike-friendly neighborhoods to serve even the people who currently wish they could live in them.

2) Bicycle ownership is a major barrier to riding, especially among poorer households

It’s pretty hard to ride a bike regularly if you don’t own one—or, even more frustrating, if your tire went flat or your brake cable snapped and you’ve never gotten around to fixing it.

The good news is that adults who know they want to ride more are about 25 percent likelier than the population at large to have at least one working adult bike in their home. But even among these interested adults, 35 percent still have no bike. This problem is dramatically higher for low-income families:

This is actually a powerful argument for (among other things) affordable, accessible bike sharing. Because bike-share systems essentially pool bike purchase and maintenance costs among many different people, they can be even cheaper than bike ownership as a way to get around.

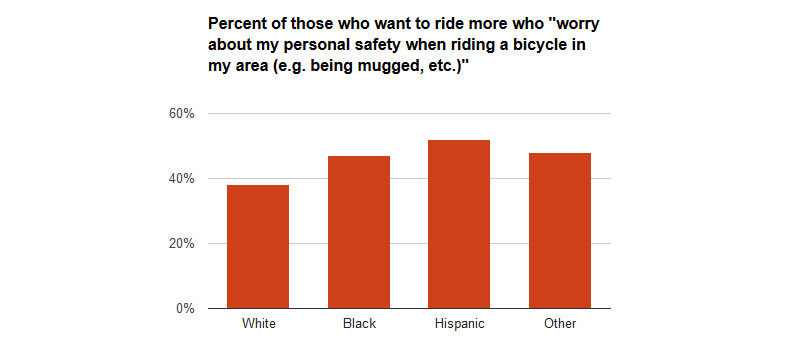

3) Fear of being personally targeted is a major barrier to riders of color

Traffic collisions aren’t the only physical threat that keeps people off bicycles. Depending on what you look like and where you live, you might be biking less than you’d like because you’re afraid of being targeted by a criminal—or maybe, sad to say, by law enforcement. On average, 41 percent of people who want to bike more feel agree with the statement below, but there’s a lot of variation by race—more than the variation by gender, region or income.

According to this survey, white adults who want to bike more are least likely to have this concern; 38 percent do. But the concern is shared by more than half of Hispanic adults who want to bike more: 52 percent.

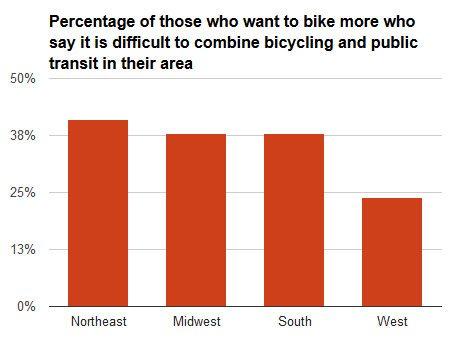

4) The western United States is much better at the bike + transit combo

Bicycles are the “secret weapon of suburban sustainable transport,” says Ben Plowden of Transport for London. By designing all-ages bikeways that connect to public transit routes and hubs, U.S. suburbs can dramatically reduce car dependence and start increasing transit quality.

But to do that, you’ve got to be able to ride your bike to the rail station, load it onto a bus rack, park it securely while you’re away and so on. Our survey found that 35 percent of U.S. adults disagree with the statement below, compared to 26 percent who are neutral and 38 percent who agree. Intriguingly, the answer to this question varies widely by region. “Interested but concerned” bikers in the western United States are far more likely to be satisfied with bike-transit integration. Cities and transit agencies east of the Great Plains should look to Asia and Europe for ideas, but they can also look west.

5) Every group worries a lot about getting hit by cars, but some more than others

There wasn’t much divide on this issue among men and women or among people of different incomes. There was a bigger difference by race and ethnicity. Black adults were the least likely to agree with this statement (though still 57 percent) and Hispanic adults the most likely (a whopping 66 percent).

But the biggest divide of all was actually by region, with 65 percent of adults in the South agreeing with this worry and only 54 percent of adults in the Midwest.

This brings us to our final observation…

6) Every single demographic group wants protected bike lanes

Not much ambiguity here.

Compared to 46 percent of the general population, an overwhelming 64 percent of people who would like to bike more say that protected bike lanes would make a difference to their transportation choices. Of this “interested but concerned” group—which, to reiterate, consists of half the U.S. adult population—only 13 percent disagreed with the statement above.

As with the other questions, we broke this finding out by gender, region, income and race to look for trends within the data. We found exactly one trend: everyone feels more or less the same way.

And that’s all we have to say about that.

[Top image: Christopher Porter / Flickr ]

One of the key problems with classifying people is that it ignores that behavior is more readily classified without showing bias.

The Geller typology would tell you that I am a “strong and fearless” rider, which I find insulting at best. I am trained to understand traffic dynamics, mostly because I sought such training–I am risk-averse by nature, and recognize that objective understanding of those risks is more effective than “I’m going to avoid what I’m afraid of, without knowing whether I *should* be afraid of it.”

Safety for cyclists is more a function of rider behavior patterns. Those behavior patterns can be classified as “pedestrian,” “edge riding,” and “driving” behaviors. A given cyclist may use a combination of behaviors in a trip, or use only one behavior pattern.

Also, from a crash-analysis perspective–looking at decades of crashes that actually happened, not those that people fear might happen–a key variable in whether a cyclist will have “absence of bad outcomes” is that cyclist’s relevance to other road users. The one constant in just about all American imitations of European bike infrastructure is that such things as bike lanes and cycletracks make cyclists irrelevant to other road users until moment of impact.