The Dillon House on Second Street has been through hell and back. Over the past decade, the century-old house flooded, burned, and is now in the process of rising from those ashes. A group called Victorian Louisville is leading the charge, quite by chance, to save the historic structure.

“We did not target the property,” Christopher White, an Old Louisville resident and director of the nonprofit Victorian Louisville told Broken Sidewalk. The group formed in response to the vacant property crisis in Old Louisville brought on during the recession. The vacancy issue had reached a tipping point in 2008–2009 when White and friend Jan Cieremans were officers of the Second Street Neighborhood Association.

“There’s always been vacant and derelict properties, but as the housing bubble burst, people were defaulting on their loans,” White said. “They were just walking away from these houses.” Previous efforts by others in the neighborhood to buy foreclosed houses never got off the ground, but White and Cieremans pressed on with their new organization.

“How could we get these houses that were just sitting there?” White asked. “The bank doesn’t want them; the owners have walked away because the value of the house has dropped below what they owe on their mortgages. What can we do?”

Meet Victorian Louisville, Inc.

Today, Victorian Louisville is directed by White, Cieremans, Bill Walsh, and John Gossman, with help from countless neighborhood contributors.

“The first houses we were looking at were on the periphery of Old Louisville,” White said. “We were looking at Hill bend, where there were all these little wood-framed bungalows. And we were looking on the east side—on Floyd and Brook—for houses we could work with and that might also help stabilize a whole block.”

The goal was to find a smaller-scale house that wouldn’t overwhelm the fledgling group. “We were not looking for a big house the size of the Dillon,” White said. “But that’s in fact what happened.” That imposing structure tucked behind the Mag Bar’s protruding commercial storefront is built of masonry and covers some 5,000 square feet.

Trouble from the beginning

As White explained, the Dillon House almost didn’t get built in the first place. While the bulk of Old Louisville was built up by the end of the 19th century, two lots remained undeveloped on the 1300 block of South Second Street in the first decade of the 20th century.

In 1907, the Dillon’s large site was tied up in the courts. “It was an extra-large lot,” White said. “A regular lot that’s 30 feet wide, plus another 20 or 25 feet.” Had the site been developed earlier, it likely would have housed another of the neighborhood’s grand Victorian mansions.

Following those legal wranglings, the property went to a Dr. Thomas T. Eaton, pastor at the nearby Walnut Street Baptist Church, which had moved from its Downtown location out to the suburbs at Third and St. Catherine streets in 1902.

“He got the property through a legal settlement in 1907 and immediately died,” White explained. “The property is then built as a duplex and in his will it’s clear that he wanted his only two children—a son and a daughter—to be joint owners of it.”

In those early years, the Dillon House’s two large units were leased to upper-middle-class families who preferred renting to owning.

A neighborhood in transition

As Old Louisville evolved in the early 20th century, the corner of Second and Magnolia became a small commercial hub anchored by a Piggly Wiggly grocery store in what’s now the Mag Bar.

White researched the changing neighborhood using Sanborn Insurance Maps and city directories. “The property on the corner where the Mag Bar is today was first developed as commercial for Piggly Wiggly on the corner—they move in in the late ‘20s. A butcher, the Dorsey Meat Market, went in next door,” he said. “That’s pretty typical back then, to have a Piggly Wiggly and a meat shop side-by-side, each having their own bay in the commercial building.”

Eventually, the grocery added a storefront at the Dillon. “In the 1928 Sanborn map, you can see the Dillon House now has this extension coming off of it going out to the sidewalk,” White said. “So slightly after the Piggly Wiggly shows up, then this commercial front was added to the Dillon House.”

The grocery was short lived. Piggly Wiggly moved out during the Great Depression leaving only the Dorsey Meat Market, which was soon joined by the Fred Karem restaurant

and a dry cleaner that set up a drop-off and pick-up location in the

Dillon storefront. The Magnolia Bar & Grill would arrive at the corner

around 1960.

The post-war years

While many of Old Louisville’s grand mansions were chopped up into tiny apartments following World War II, the Dillon House remained a duplex. “The number of occupants, though, got larger and larger,” White explained. “You had more people occupying the same two dwellings that were in there. You simply see more names in the city directory. Some of them look like they’re related names, maybe siblings, and others are not.”

Even though the property was not subdivided, it still encountered financial problems in the mid-20th century. The house went into foreclosure several times and again was burdened with legal problems.

By the 1970s, Jimmy Dillon and his wife owned one half of the duplex while the other half was owned by the Wu family which operated a hand laundry at nearby First and Oak streets. Dillon eventually bought the Wu’s interest in the building.

After his wife passed away in the 1980s, Dillon continued to live in the building on the second floor as a widower, renting out the first floor, a small room on the third, and an apartment over the garage. This arrangement lasted for nearly two decades more, although by the 2000s, Dillon was living alone in the mansion.

Tragedy at the Dillon House

In the summer of 2009, heavy storms flooded the area around the Dillon House. “That whole area between Second and Third—a low area—flooded very badly,” White said. “Jimmy’s house had taken in a lot of water.”

Those floodwaters turned to a deadly inferno after Dillon hired workers to refurbish the house’s water-damaged floors. Workers had been using polyurethane, which sparked the fire.

“By the time the fire happened, there was no one renting—he was all alone,” White remembered. “He was about 90 or 91 and deaf and having little strokes all the time and was in there when the fire happened.” The fire took Jimmy Dillon’s life.

Afterwards, the fire marshal decided the fire was caused by either spontaneous combustion from a pile of rags workers left behind or else a cigarette thrown into a pile of debris in the back of the house. In addition to the insurance settlement, the Dillon estate later won a wrongful-death lawsuit.

Dillon House in Limbo

The fire collapsed the roof of the Dillon House, leaving its burnt masonry shell looming over Second Street. The executor of the estate, Dillon’s nephew living in Massachusetts, was not interested in the house, instead leaving it to decay.

“There were a lot of liens on the house, and the city couldn’t get him to come back to Louisville to settle,” White said. By the winter of 2010–2011, the city issued a demolition order for the property in an effort to get the nephews attention.

Victorian Louisville was watching these events unfold closely. “It’s interesting that that’s the reasoning [the city] had,” White recalled, “but it did get him to come back and we were ready then to negotiate with him.”

The timing was right. Victorian Louisville had just received its 501c3 nonprofit status from the IRS and was ready to take on the house as a donation if the nephew accepted the proposal.

“We had notified the city that we were entering the process [to acquire the house],” White said. “We let them know we were working with the estate of Mr. Dillon.” A deal was struck, and Victorian Louisville received ownership of the property on Derby weekend of 2011.

“Everything worked out pretty well,” White said. “He gave us the house and the city took off all the liens—they really took it back to zero—and we were able to get the taxes waived. The city was very helpful once they had someone to step up and take the property.”

A Daunting Rehabilitation

Victorian Louisville suddenly had its first project—and it needed major work just to keep it standing.

“I can’t tell you how frightening it was to go into that basement and look at what was down there,” White recalled. “It was a terrible place because the house was collapsing in its center.” Load-bearing piers and beams in the basement were rapidly compressing, shifting, and twisting under the weight of the house. “They were ready to drop,” White said.

That summer, the group raised $40,000 from citizens in the neighborhood to get started.

To save the Dillon, crews first had to clear out all the fire-burned debris inside the structure. “There was a lot collapsed inside,” White recalled. “So we got the house cleaned out down to the studs—it was just a shell.”

Next, new structural elements were installed. “We had to lift the house up, so it had to be as light as possible,” White said. All the plaster was removed and the fireplaces taken out of the house.

Still without a roof, the house was taking in water. “We had all of these blue tarps hung like upside-down circus tents catching the water and funneling the water out through a window while the house was cleaned out and then lifted,” White said.

With the house stabilized, rebuilding could begin. “We started the task of rebuilding the inside of the house—the framing, taking down damaged brick and then rebuilding the brick windows and arches and doorways,” White said. His group was careful to only do what was absolutely necessary to stabilize the house due to funding restrictions.

Victorian Louisville has raised and spent $150,000 in saving the structure. White speculated that it could take another $300,000 to make the structure occupiable.

Now, the basement has been completely repaired and the framing on the first and second floors is complete. The third floor still needs to be rebuilt and eventually new windows will be installed. “We’re not bothering with windows just yet,” White said, “that’s an extraneous expense.” A rubber membrane was attached to the floor of the third floor, creating a roof and stopping water from pouring into the house. “That has effectively given us a dry inside.”

“Right now we need about $27,000 to $34,000 to get the third floor rebuilt with a roof,” White said. “That $7,000 margin is because labor is being supplied by the department of corrections Dismas House parolees, so we don’t have to pay for that. If we had to pay for it, we’d have to factor in more money.” Windows would be a few thousand more.

Learn how to contribute to the project on the Victorian Louisville website.

It’s been six years since the fire and there’s still a lot of work left to complete. Some brick exposed to the fire and elements over the years will be rebuilt. “We’re going to have to take down some of the back brick wall and the sides down to a level where we can get good brick and mortar and then rebuild that back up,” White said. “And then build a wood-framed third floor with a proper roof.”

Today, a pizza shop leasing the ground floor retail space generates a small income for the project and helps pay a construction loan from Republic Bank.

The Development Vision

Soon, the group will be faced with a tough decision. “Do we want to pass this along to a developer, who will take it on to finish, or do we want to keep it and take it all the way ourselves,” White asked.

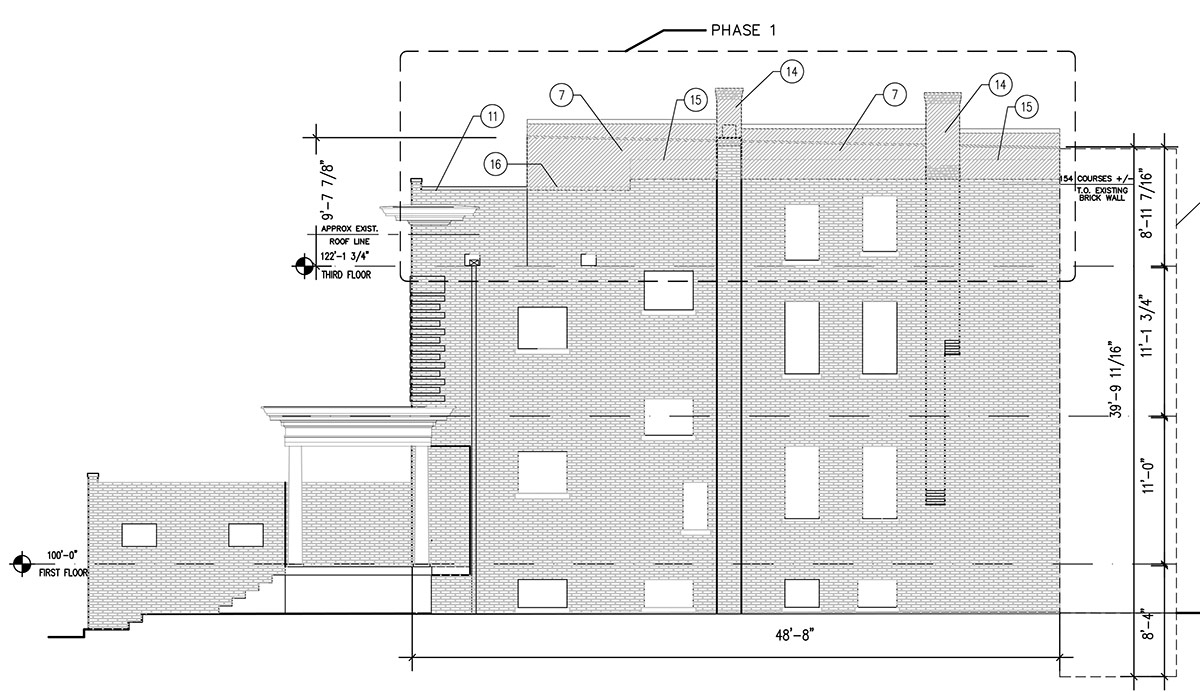

Either way, Victorian Louisville has drawn up architectural plans with the help from architect Madonna Wilson to rebuild the third floor and create a mixed-use development with residential, office, and retail use in its existing storefront.

While the original structure was only two-and-a-half floors, the restored building has been approved for a full third floor, although you’d never be able to tell from below. The third floor is set back from the front facade so it won’t be visible from the street. That allows small terraces overlooking Second Street from behind the building’s tall parapet.

White said there are a couple layouts that could be used in the final design, including two large dwellings on the second and third floor, or three smaller townhouse-style units side by side. A final decision on layout has not been made. The first floor could be office space or potentially a live–work setup. Units would likely range from 1200–1300 square feet.

The Long Road Forward

Victorian Louisville has its work cut out for it, but if White is any indication, the group will persevere and see the Dillon House fully restored. If you’d like to contribute to the effort, check out the group’s website with details on how to make a tax-deductible donation or become a member of the organization.

White cares deeply about Old Louisville and its long and winding history, having meticulously restored and researched his own home nearby. He and his colleagues are thorough in their undertakings and the Dillon House—and all of Old Louisville—stands to benefit from their hard work and attention to detail.

While it’s too soon to say what’s in store for Victorian Louisville—there’s a lot of work left to finish at the Dillon House—White said they hope to remain active in the neighborhood.

“Before we even had the Dillon Property, we had a list of properties we were looking at,” he said. “The reality is we have to get this one taken care of, and whatever the proceeds are from that then we’d start to look for other properties.”

Could the Dillon house be haunted? My daughter currently rents the second floor apartment where there was once a deadly fire. she and her roommates have had some strange events occur, including their mattresses shaking randomly from

Side to side ….. The apartment was beautifully renovated.