Public design review in Louisville is, without exaggeration, in serious trouble. Last Wednesday’s committee meeting of the Downtown Development Review Overlay (DDRO) is the clearest case yet in a string of recent regrettable public reviews demonstrating panels like this are either unable to hold back political pressures surrounding the city’s important development projects or unwilling to uphold the rules and guidelines they are tasked with safeguarding.

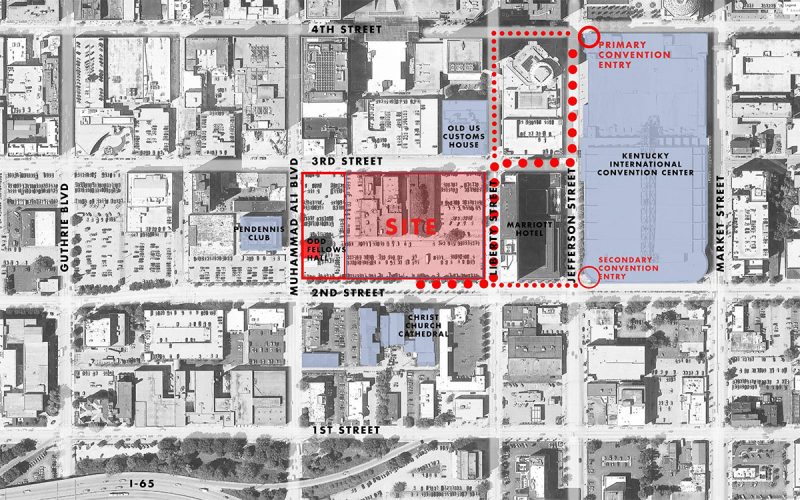

In two votes on Wednesday, following over four hours of presentations, testimony, public comment, and deliberation, the DDRO voted six to two to approve clearing the Water Company Building and six to two to approve the Omni Hotel & Residences development with eight conditions (details below). That meeting was a continuation of a previous four-hour-long meeting two weeks prior on July 15.

These were not your typical DDRO meetings, and the Omni is not your typical downtown development project. The Omni decision may have been the biggest decision ever made by the DDRO committee in its 23-year history. During both meetings, crowds packed the courtroom in the Old Jail Building to speak about the case—most supportive but with mixed feelings. Crowds this size are rarely seen at DDRO meetings, and the last such throng was during hearings for Museum Plaza almost a decade ago when the community was overwhelmingly in support of the project.

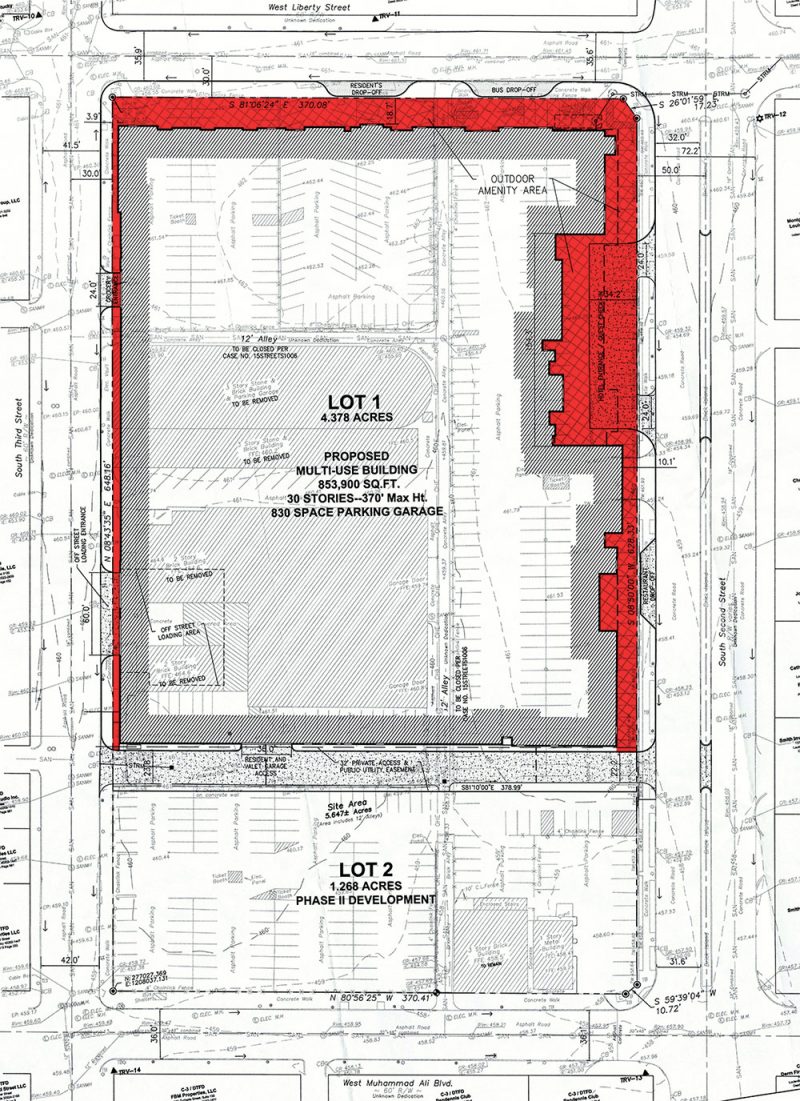

With a budget climbing over $289 million, the Omni Hotel & Residences represents a major, and as Mayor Greg Fischer puts it, transformational rebuilding of an entire block in the center of Downtown Louisville. The DDRO typically hears about much smaller, much-less-complicated projects, with much less public interest than this one, and it showed in the level of discourse around the development. In a project suffering from a lack of public input and transparency, this public review was a crucial part of making the project right.

But what is the DDRO’s job, anyway?

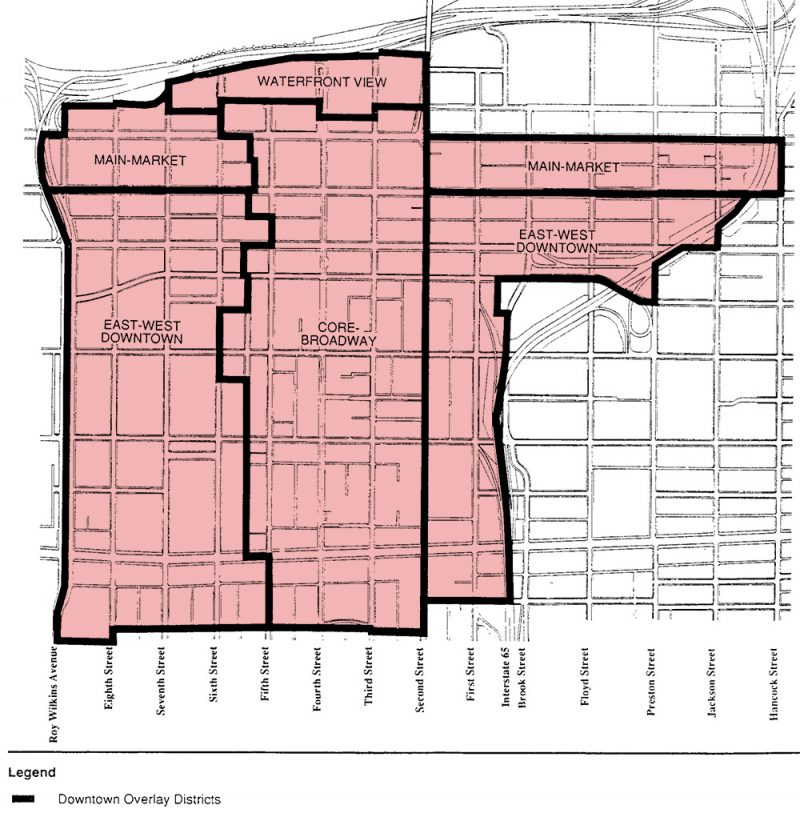

The DDRO dates back to 1992 when the, then, Board of Alderman established it on the recommendation of the 1990 Downtown Plan (Metro Council reestablished it in 2007 post-merger). “The design review process provides a forum for citizens and developers to work toward achieving a better urban environment through attention to fundamental urban design principles,” according to DDRO documents.

The job of the DDRO committee is quite simple. According to the city:

The Overlay’s specific task is to preserve, conserve and protect the “historical, cultural, architectural, aesthetic or other distinctive areas” of Downtown by reviewing proposed developments in accordance with established principles and guidelines addressing elements such as “building setbacks along streets, open space, off-street parking, landscaping, paving, lighting and streetscape furnishings, fences and walls, signage and public amenities and, in addition, elements of urban design such as building and street wall character, and building mass and form.”

Any project built Downtown must secure a permit “certifying compliance with the applicable District Guidelines,” the ordinance establishing the DDRO reads. “Guidelines and the distinctive characteristics for each District shall be the basis for evaluating applications for development proposals.” The ordinance instructs the committee that “All Principles which are part of the Guidelines for a particular District, must be addressed before a Permit may be issued.”

Louisville has a clear and long-established set of goals for Downtown that the DDRO is meant to safeguard in their approval process. Those goals, principles, and guidelines expand upon Cornerstone 2020, the city’s land-use code, and are tailor made for downtown’s unique urban qualities.

“Louisville Land Development Code is…a form based code regulating the physical form of development,” according to the ordinance. “The Code addresses basic elements of site layout and building design, streetscape, open space, parking, signage, and public art that are appropriate for an urban downtown setting.”

That means the committee is fully within its right to ask a developer to change the form of the project, but it’s cautioned against dictating actual architectural design. Committee members are required to know the difference between form and design when they deliberate each project.

The review panel is set up to be flexible so as to not stifle entrepreneurship. The rules and guidelines might not fit every development scenario or they can offer bargaining chips with which the committee can ask for other improvements in lieu of conforming strictly to the guidelines.

The eleven-person committee includes the Director of Metro Planning, Downtown’s Metro Councilperson, five downtown business owners or residents, and architects and landscape architects, among others. Committee members are asked to interpret the DDRO guidelines and Cornerstone 2020 as part of the Downtown Form District and evaluate if a proposed development fits or doesn’t fit within that framework.

The cast of characters

First, let’s meet the panel: The eight committee members in attendance at Wednesday’s hearing included Emily Liu, Director of Louisville Metro Planning & Design Services; David Tandy, Councilperson for Metro Louisville District 4, which emcompasses Downtown and many surrounding neighborhoods; Ed Kruger, a principal at Bravura Architecture; Scott Kremer, principal at Studio Kremer Architects; Tim Mulloy, President of Mulloy Properties and DDRO Chair; Dan Forte, Vice President of Programming at the Kentucky Center for the Performing Arts; Jon Henney, Land Planner at Gresham, Smith & Partners; and Mike Leonard, Chief Operating Officer at Hogan Real Estate.

Also sitting with the panelists was John Carroll, their legal counsel and Assistant Jefferson County Attorney who was there to answer questions about the ordinance and the process and make sure voting happened according to the books.

Representing the applicant, Mike Smith spoke for Omni and Jeff Mosley spoke for Metro Louisville. Bob Keesaer, the city’s Urban Design Administrator, was also on hand to discuss the staff report he prepared stating the case why the project should be approved.

Approved with conditions

Before we dive in, we should first mention the eight conditions attached to the Omni’s approval. Five of them are from Keesaer’s staff report and three more were added on by the committee. Briefly summarized, they are:

- Public art should be incorporated into the development, inside and out.

- Any signage must be submitted to Planning & Design staff for approval.

- Additional perforated metal screening should be added to the garage to mask ramping floor plates barred by DDRO guidelines.

- Glass-paneled garage doors should be used on the loading dock and garage on Third Street.

- Archaeological discoveries should be reported to staff for documentation.

- Precast concrete cladding planned for the slab towers should be submitted to Planning & Design staff for approval.

- The Phase 2 site should be landscaped within six months of completing the Omni, until a further use for the site is determined.

- Pedestrian amenities such as benches and bike racks should be included in the development and submitted to Planning & Design staff for approval.

Third Street was on the line

The Omni stretched or broke many of the guidelines, but in most places they were minor enough to be overlooked or serve as bargaining chips for amenities like public art. In general, the Omni’s design looks pretty good and was sailing toward approval. The general project is, after all, a good one. Except on Third Street where it breaks apart into a city-fabric-shredding mess—and the committee discussed this at length.

“I am incredibly in favor of this project—it would be very exciting to see another significant construction site in this city, but I’m no closer to a yes than I was two weeks ago,” Kremer said during the meeting. He expressed his concern over the lack of response from Omni between the two meetings. “I don’t think they’ve addressed a single one of these pieces that are really important to preserving Third Street.”

He was right. The Omni team had made no revisions in the preceding two weeks. They presented exactly the same plan that was discussed at the first meeting, with all of the same poor urban design along Third Street.

“There are way too many guidelines that have been tripped over or violated. Most of those are on the Third Street side,” Kruger added. “With that many things, I’m not comfortable—and I don’t think this body should be comfortable—with saying yes to this project.” The audience responded with applause.

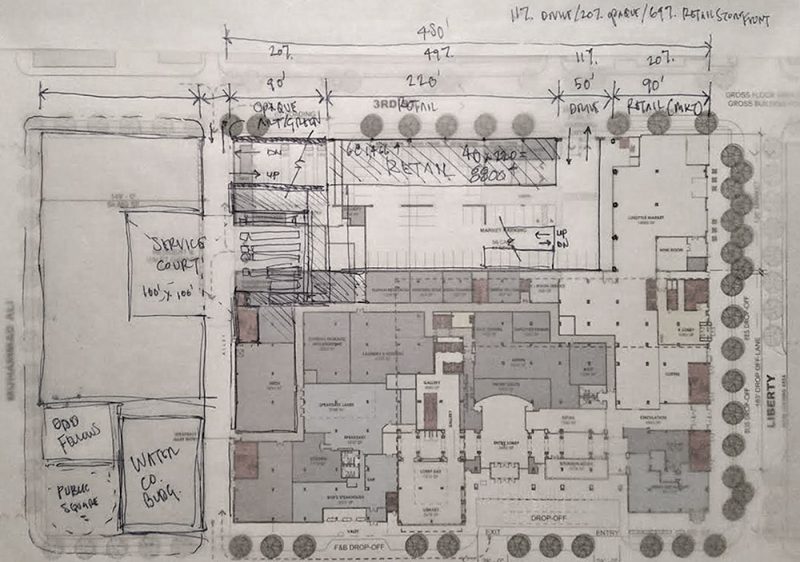

The biggest concerns discussed by the panel related to retail along Third Street, the orientation of a Third Street–facing loading dock, and screening for the garage’s ramped floors. One of the major issues from the initial Omni plan—materiality—had been addressed at the last meeting with Omni’s updated design. Then, concrete block was replaced with brick and the general massing of elements was rearranged and refined.

Kremer motioned for two conditions to be added to the approval: requiring retail be built concurrent with the project and that the loading dock be rotated 90 degrees to face a new alley. Kremer, an architect, had sketched the loading dock layout over the Omni’s plan to make sure it would work before the meeting.

“With regard to circulation, [guideline] SP4 specifically says we are to minimize interruptions to the street wall with regards to the loading dock,” Kruger, the committee’s other architect, noted. “And here, I don’t think we have. We have a very wide loading dock that is going to be always open onto Third Street. The dock doors will never be down. It’s another inhospitable piece [of the project].”

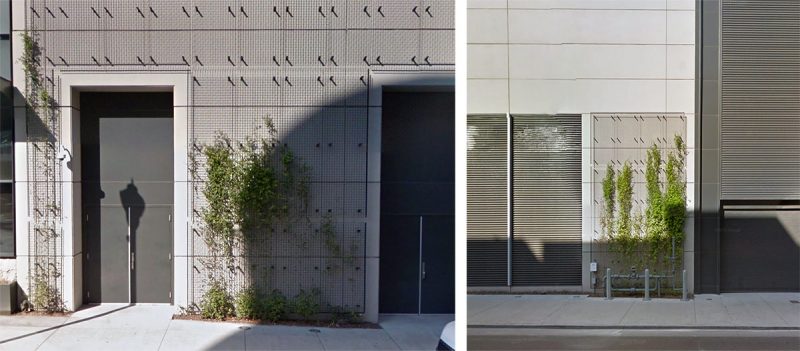

Kruger compared Third Street to the loading dock portion of the recently opened Omni Nashville, which shows many design similarities including trellises and a carbon-copy curtain wall. He noted the general unsightliness (not to mention stench) of an active loading dock that remains open most of the day. He referred to Google Street View images from May, which also show what the trellises should look like a couple years after our own Omni opens.

The debate around Third Street showed how everyone involved—Metro Planning staff, the Omni team, and many committee members—struggled to understand what makes a city active, pedestrian friendly, and vibrant.

As mentioned above, one adopted condition from Keesaer’s staff report called for including glass loading dock doors. “At some point those doors will be shut. When they are shut, even if it’s after hours…you’ll want to have an engaging facade that’s open and transparent,” Keesaer said. “Having glass doors, much like what you see at oil change places where you can see the cars being worked on—you see work, you see activity—to be able to see that versus just a metal panel door was my focus on that particular recommendation.”

That statement—that glass panels on a loading dock door would be engaging and active for the pedestrian—characterizes the low level of concern Omni and the city are giving Third Street.

Next up for discussion: retail. Both Kruger and Kremer listed numerous guidelines broken under the current plan, including the fake storefronts on Third. “With regard to the vitrines, [guideline] BP2 calls for articulating the facade and energizing the facade,” Kruger said. “Vitrines are poster cases in the wall.”

During presentations from Omni and the city, these fake storefronts were repeatedly referred to as sidewalk activation devices that improved the pedestrian experience. It should be quite clear that a static billboard does not activate the sidewalk. Despite an aesthetic upgrade, Third Street remains a blank wall.

“I can’t agree that this development contributes to the overall urban design quality of downtown,” Kremer said.

The committee floundered here on the difference between form and design and the fundamental role of the DDRO. “I really struggle with redesigning the ground floor of somebody’s project,” Leonard said. No one on the panel had called for changing specific design elements on the project, just form issues with the use along the sidewalk level.

“There’s a lot of points that Ed [Kruger] is bringing up, and I do agree with them,” Forte said. “But I’m not willing to sacrifice the project overall.” Upholding the standards of Louisville Downtown Development guidelines and the city’s land development code won’t sacrifice any worthy project—and Omni is not going to walk away from nearly 50 percent subsidy over a request to add retail in an oversized parking garage.

“In a perfect world, would there have been ways we would have liked things to have been done? I would agree,” Tandy said. “Were we at a different juncture in the process it would afford us different opportunities.” What’s missing here is that when a project appears before the DDRO committee, it’s not too late for changes—it’s the exact appropriate time. That’s the point of the DDRO.

“I think there’s much unresolved,” Kremer added. “They’ve just completed schematic design. What I did in two hours on my kitchen table [laying out an alternative loading dock] they could do in two weeks, and they could still be relatively on schedule. It’s not going to affect the overall project.”

Both conditions were voted down by the committee, five to three.

One humorous aside: before the vote, Tandy left the room to make a phone call. Carroll wanted to wait for him to return before voting but a quorum was in place, so the vote proceeded in his absence. Upon hearing this, a city official in the audience apparently worried the conditions might pass sprang from his seat to find Tandy, who is a regular absentee to DDRO meetings, and rushed him back just in time for his vote against the change.

While there will be no retail on Third Street, the Omni team said the garage would be built with structural modifications to allow vitrines to be converted to retail at a later date. But with PARC, the city’s parking authority, operating the garage and proclaiming at the meeting that they’re not in the retail business, this retail will be a long way off, if it’s ever built at all. “We want actual retail on Third Street,” Kremer said. “Not the notion of retail, not the prospect of retail—we want actual retail.”

Components of a project that aren’t built concurrently with it tend to never be built at all. For instance, a decades old parking garage on Sixth Street between Main and Market was designed to accommodate retail, which was never built.

The Bungled Case of Omni

Besides the committee’s timidity, there were a number of other laughable problems with the procedure of the meeting. Let’s take a look at two.

Near the end of the meeting, Kremer made a motion to defer the committee’s decision until Omni could continue with design development to address Third Street. Carroll, the legal advisor, responded saying that under the DDRO ordinance, the committee could not defer a case twice, prompting Liu to agree with him.

While it is true the ordinance only allows one deferral per case, the DDRO had not formally deferred the case previously. Rather, DDRO chair Mulloy called for a continuation of the meeting without holding a vote. “Ladies and gentlemen, we are out of time for today,” Mulloy said, ending the July 15 meeting. “We are going to continue this meeting two weeks from today…There is still much to discuss.”

A deferral under the DDRO ordinance is a formal decision of the committee upheld by a majority vote:

The Committee shall, by majority vote of the members present, make a decision, supported by written findings of fact, which shall approve the Permit, approve the Permit with conditions, deny the Permit, or defer consideration of the application until the next meeting of the Committee. Consideration of an application shall not be deferred more than one time. If the Committee defers consideration of an application it shall state the reason for such deferral.

Kremer asked for clarification between a deferral and a continuance from Carroll. He responded that the last meeting was a deferral “because there was new evidence coming which was filed.” Mulloy asked for specific language from the ordinance, but while Carroll looked up the language, the committee continued to ask questions about the project and forgot to return to the ordinance clarification.

It remains unclear whether Kremer should have been allowed to motion for a deferral, which would have pushed Omni back to the drawing board along Third Street and potentially changed the outcome of the hearing.

Carroll fumbled again when Kremer proposed his two conditions—retail and relocating the loading dock. Before the vote on those conditions, Carroll asked Omni and the city what they thought of the idea. “Jeff, are those amendments to the findings acceptable?” he asked. Mosley responded, “Omni and the city cannot accept the amendments as tendered.” “Okay, that’s what I wanted to know,” Carroll said.

A stunned Kremer responded, “I don’t know that that’s appropriate to ask an applicant or representative.” The opinion of the applicant, in this case Omni and the city, about the conditions the DDRO might impose on their project, is of no concern and can only serve to sway the vote of the committee.

“No offense to Jeff Mosley, but why is that appropriate to ask an applicant what they think of our motions or business?” Kremer asked Carroll. “It’s just a matter of agreement, courtesy,” Carroll responded. “If you’re asking changes to the plans, you should certainly ask the applicant if they agree to the change.”

Henney then asked, “If we’re putting [in] conditions, is this something that the applicant has to agree to?” Carroll responded, “The applicant has already said he won’t agree to them. He doesn’t want to agree to them. But you can impose them if you feel they are appropriate.”

Carroll repeated this questioning of the applicant when Kruger motioned for his three conditions that ultimately passed. The fact that this happened at all is an affront to the public process.

Omni is at the BOZA today

This morning, the Board of Zoning Adjustments (BOZA) is reviewing waivers and variances needed for the next round of approvals for the Omni.

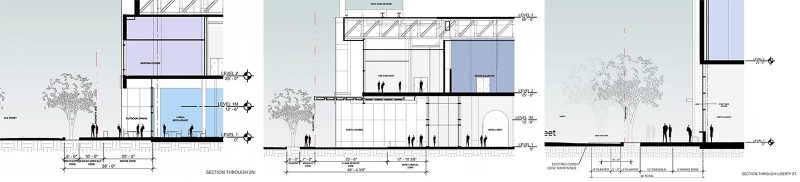

One of those is a waiver to allow Omni’s slab towers to ignore building setback guidelines. Codes requiring buildings above 14 stories to step back their massing from the street to increase light and air on the sidewalk. The shorter slab is only one story higher than the 14-story setback and is situated along wide Second Street, meaning it would have little impact. The taller slab on Liberty cantilevers out over the sidewalk to the property line, getting wider as it climbs instead of narrower. That waiver will likely go through without any trouble.

The other is a variance to allow the building’s ground-level facade to be set back from the property line on all three facades—Second, Third, and Liberty streets. Cornerstone 2020 requires all new buildings to be built to the property line to maintain downtown’s street wall. Where sidewalk widths are limited, the code allows for minor setbacks to accommodate a better pedestrian experience. In the case of the Omni, however, those setbacks are substantial, widening sidewalks past the city’s mandated maximum sidewalk width of 20 feet in many circumstances.

As the Omni facade zigzags in and out to define specific masses, create pockets of outdoor dining, and notch in a wraparound driveway, the property-line setback changes from a few feet to more than sixty.

That’s not inherently good or bad, but it does impact downtown’s urbanism—and it stretches more guidelines and land use codes. For instance, a too narrow sidewalk next to a massive building will feel cramped, but conversely a sidewalk that’s too wide without enough activity will make a street feel overbearing and lifeless. It’s important to strike the right balance.

The Omni’s Liberty Street face is set back a minimum of 18 feet 7 inches from the property line. What we thought initially was a road diet actually represents a road expansion as the street’s existing curb line and four lanes of traffic are maintained and a new drop off lane is carved out of the current sidewalk area.

This setback is allowed under under code since the Liberty facade spans the entire block from Second to Third streets. From curb to building, the sidewalk on Liberty will range from 25 feet to 34 or more feet wide, well beyond the maximum sidewalk width of 20 feet.

On the Second Street side, sidewalks range from 36 feet at the corner with Liberty where a restaurant sits, to approximately 22 feet for the rest of the facade. The main hotel entrance is set back over 64 feet behind its porte-cochère. Third Street is set back slightly, but plans are unclear as to the exact amount. Part of the variance is for this Second Street setback, as the maximum setback under code is 15 feet with 60 percent of the street wall maintained at the property line. Some portions of the widened sidewalk are also allowed since the upper stories project overhead.

A lot about these setbacks are great—the mass of the new building will be offset by more comfortable sidewalks, there’s more room for trees, and the hotel’s restaurants get outdoor dining space. According to Omni’s plans, the sidewalk does appear to be differentiated well into lanes of trees, walking areas, and dining areas. But is a 35-foot sidewalk too wide? Is a 25-foot sidewalk too wide? BOZA will look at these questions in its hearing. But BOZA is the same committee that issues the 400-foot setback variance to the West End Walmart citing economic development benefits, so it could just as easily rubber stamp these setbacks as well.

We’re getting an Omni

Despite the inconsistencies in protocol and the lack of foresight of the DDRO, Louisville is getting an Omni, and that’s going to be great—mostly. Omni’s brand is strong and it’s not a company with a reputation to skimp on details. While the HKS-designed Omni Nashville also has a street-killing loading dock, the rest of the Omni Nashville is designed and built very well—take a look at the galleries on its website of interior and exterior spaces. HKS is sure to bring that same level of refinement to Louisville’s Omni.

What’s more, Louisville will finally fill in an enormous chunk of surface-level parking lots that made it all the way to the Elite Eight in Streetsblog’s 2013 Parking Madness bracket (we lost to Houston, but that seems completely appropriate). While mega-projects like the Omni don’t pack in the active uses like in Nulu or along West Main Street, it will relocate the center of gravity of Downtown, giving Second Street a much needed boost. The Omni will, for the most part, drastically improve on existing conditions, and, who knows, maybe its presence will help fill the years-vacant Cathedral Commons ground floor retail space across Second Street.

It is regrettable that the project was fraught with so much public upheaval and tight-lipped secrecy from the city. The community supports the Omni and would have supported the Omni through the contentious design reviews of the past months more if given a chance to participate. And Louisville could have ended up with an even better product along Third Street. We hope this is a lesson for future large-scale development downtown and that the city will learn from its mistakes.

Unfortunately the lessons were already learned from the Galleria. The process is totally broken. Intentionally. When a mayor takes it upon himself to stack the deck, demo non emergency status historic buildings on a weekend, and have his junior henchmen craft fake changes that amount to nothing but, surprise, fake improvements, in a back room, and the public very much tells him this all smells rather fishy, and yet they steamroll over the guidelines the staff and the urban development code, well.

The setbacks are just more of the same, Kindred style. And you know they did it in a very amateur very unprofessional and yes very shady way. We have all lost. And these people are holding us all hostage. It’s the Confederacy of Dunces. Design review has done more for this city than any other single effort. This Mayor has taken over four decades of very hard work and sold it all down the river because he and his very ignorant advisors haven’t a clue how to build a real city or what a value system looks like.

All the real talent was in the audience. Kudos to the professionals on the board who held out for the process. The rest were already told how to vote. Or else. Transparency. Sustainability. Vision.

Not. We’ve learned nothing. And nothing is what we will end up with. Again.

Re: retail vitrine – why not use these for public art with a curated rotation? The area is essential a facade for a parking lot, which faces another parking lot across from 3rd st. Could there be enough space for a european-style news stand/ snack shop/flowers/fruit stand? A giant refridgerated vending machine? LOL

I have zero problem with the Omni progect, but where was the DDRO when the Marriott was built. Aside from those ugly run down Schneider buildings on Broadway and the unsightly 800 with it’s off center top, start up glass panels that stopped after two apartments, the Marriott has to be the ugliest design in a city full of ugly designs. I won’t even bring up Waterfront plaza with those cheap looking light houses on top, and a roof border that goes only 3/4 around. The Marriott’s back has no connection with the front, and the top looks unfinished, yuk!

Exactly the Omni’s flagship corner, at 3rd and Liberty, is going to be ruined by sharing it’s corner with a parking garage and the blank wall of the Omni that offer nothing of interest and cars speeding by on their way out of the city, which isn’t even to mention the rest of the ugly back of the Marriot that everyone who patronizes the Omni’s businesses will have to look at. It’ll be a tough draw getting people to walk down Liberty from 4th to actually visit the Omni because Liberty is so dead. Maybe Louisville will finally understand you can’t just write off block size sides of buildings in the middle of downtown; too bad the Omni is doing the exact same thing to 3rd street.