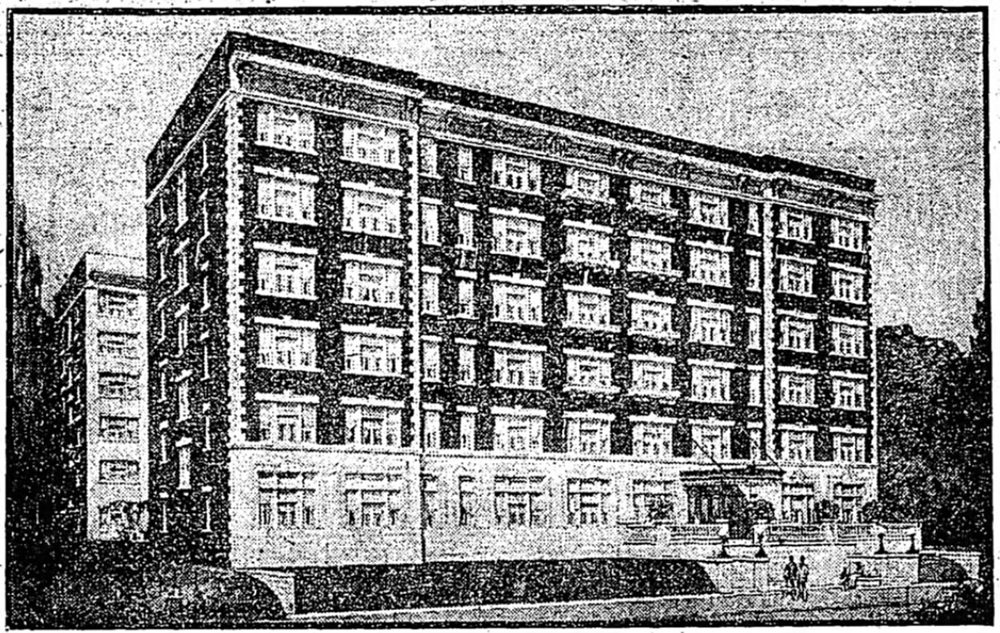

Had it been proposed today, the Puritan Apartments on the corner of Fourth Street and Ormsby Avenue in Old Louisville might have caused an uproar. When it opened in 1914, the six-story building was distinctly different from the detached, single-family homes that lined the neighborhood’s streets.

The Puritan’s scale dominated the residential street, standing nearly twice as tall as surrounding two- to three-story structures. The building itself required demolishing a series of sturdy brick and stone mansions that stood in its way. And the materials it was built with—brick and terra cotta—represented the cheap new construction method of the day. Where buildings older than the Puritan were typically built with hand-carved stone, this new terra cotta was a mass-produced molded alternative of the machine age.

In fact, advertisements celebrated that the Puritan was “scientifically planned” to eliminate the “servant problem.” Units were small and efficient so residents needed not hire domestic help. The building generally presented a blank wall to the street, set back behind a grassy berm as is typical of houses in the area. (Inside on the basement level, there was a retail grocery store.) And the apartments were expensive. In 1929, rents ranged from $65 to $150 per month. In today’s dollars, that would be $900 to $2,100 for a unit.

But today, the Puritan stands as a landmark structure in Old Louisville. We’re glad to have it. And when it opened, the city welcomed it proudly. Construction has changed again, and that once cheap terra cotta is now quite expensive by our modern standards. It’s scale is not so out of place with a century’s patina and it’s quite at home in Old Louisville.

Today, Louisville struggles with the same kind of new development. And there hasn’t been a lot of examples, good or bad, in the urban core with which to draw experience. Questions over scale, preservation, design, urban contribution, and building quality have brought with them praise and disgust for various apartment buildings proposed around the central city.

For sure, some of the new buildings proposed today are better than others. Here on Broken Sidewalk, we’ve criticized elements of the 310@Nulu, the Amp Apartments, and the Axis on Lexington Road and praised others like the Main & Clay apartments. I’m adding to that latter list the proposed Phoenix Hill Tavern apartments by Columbus, Ohio–based Edwards Companies.

Located on a triangular assemblage on the corner of East Broadway and Baxter Avenue, the Phoenix Hill Apartments bring 280 units, 30,000 square feet of ground floor retail, a compact layout, and a variegated design to a stretch of street pocked by parking lots and concrete block buildings.

Also within the project site are a number of historic structures, a dozen houses and three commercial buildings. Five of those houses will be left in place, renovated, and likely sold or rented once the project is complete while the facades of an Italianate house and a commercial building will be incorporated into the new structure.

It’s not preservation, but it’s a compromise on a complicated site. And this block has been a development pickle for decades. I’m saddened to lose a couple of the old commercial buildings on Baxter, but to see a cohesive and urban project like this proposed on the site of parking lots and irregular parcels is exciting. It will change the character of the area, certainly, but for the better.

The four- to five-story scale of the buildings is an appropriate height to complement the grand entrance and spire of Cave Hill Cemetery across the street. This height will help focus attention on the landmark limestone spire rather than dwarf it. In fact, most of the context on the Baxter Avenue side of the project consists of cemeteries (Cave Hill and Eastern), making density here even more appropriate. Open spaces like cemeteries and parks make great locations for added density.

The design doesn’t scream look-at-me as others have attempted, but they do provide valuable urban context with an active street wall on Baxter. While I believe that activity would have been appropriate to continue around onto East Broadway, developers kept that frontage residential at the request of neighbors.

The Phoenix Hill Apartments is the type of project that can actively reduce traffic congestion as it places hundreds of new residents within walking distance of their retail destinations—and it adds to the street with new retail of its own.

This project will be a boon for the corridor’s small businesses, increasing walkability, and reducing the need to drive for short trips. Plans still call for a 550-space parking garage tucked inside the project and not visible from the street, which I believe is overkill, but the reality that this project reduces the need for cars remains unchanged.

The old structures in the area mostly date to the late 19th century when Louisville was a very different place. Back then, this was the edge of town and the entrance to a toll road leading to destinations south. Buildings topped out at two stories and many houses at one. For much of the 20th century, the corner was either a gas station or a parking lot, contributing nothing to the area’s urban character.

Today, this corner is in the heart of the city. It sits at the beginning of the most active part of the Baxter-Bardstown corridor, a gateway to Downtown down Broadway, the Highlands, and to Phoenix Hill and Irish Hill. That confluence only stands to benefit from a project like the Phoenix Hill Apartments.

Louisville has grown up and gotten bigger. There’s absolutely no reason that we should still be bound by the scale of 19th century hinterlands in the core of a 21st century city.

But Louisville has not seen this kind of urban-style development activity for nearly a century and it sometimes feels like the city doesn’t know what to do about it. On one hand, there are NIMBYs whose good intentions would shrink the project and its ability to contribute to a vibrant urban neighborhood—or undermine the economics that make such a development possible. On the other side, there are development-at-any-cost parties that would have a Walmart built on this corner if the proposal came up. The best path forward is somewhere in the middle.

What’s now evident with the resurgence of development in the core city is that Louisville is not a desperate city. We don’t need to beg for developers to build here—to build a quality product here. The city should stand up and be confident as development returns to the core. Don’t be afraid of urban buildings, don’t settle for satisfying a developer’s bottom line, and don’t idly let bad urban form be built for the next generation to fix.

Louisville needs to look at the various products being offered and built around the city, learn from them, and demand the best product possible. One that makes Louisville a more walkable, more vibrant, more attractive place to live. That happens on a case-by-case basis. I believe we’ve found that with the Phoenix Hill Lofts and I’m excited to see this project move forward.