Protected bike lanes are now officially star-spangled.

Eight years after New York City created a Netherlands-inspired bikeway on 9th Avenue by putting it on the curb side of a car parking lane, the physically separated designs once perceived as outlandish haven’t just become increasingly common from coast to coast—they’ve been detailed in a new design guide by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA).

The FHWA guidance released Tuesday is the result of two years of research into numerous modern protected bike lanes around the country, in consultation with a team of national experts.

“Separated bike lanes have great potential to fill needs in creating low-stress bicycle networks,” the FHWA document says, citing last year’s study by the National Institute for Transportation and Communities. “Many potential cyclists (including children and the elderly) may avoid on-street cycling if no physical separation from vehicular traffic is provided.”

Among the many useful images and ideas in the 148-page document is this spectrum of comfortable bike lanes, starting with bike infrastructure that will be useful to the smallest number of people and continuing into the more broadly appealing categories:

In addition to a brief review of scientific literature on protected bike lanes in the U.S. context, the new federal guide also offers renderings of many designs that are becoming familiar in some U.S. cities but are still new to many street designers, such as bend-out bike lanes at intersections:

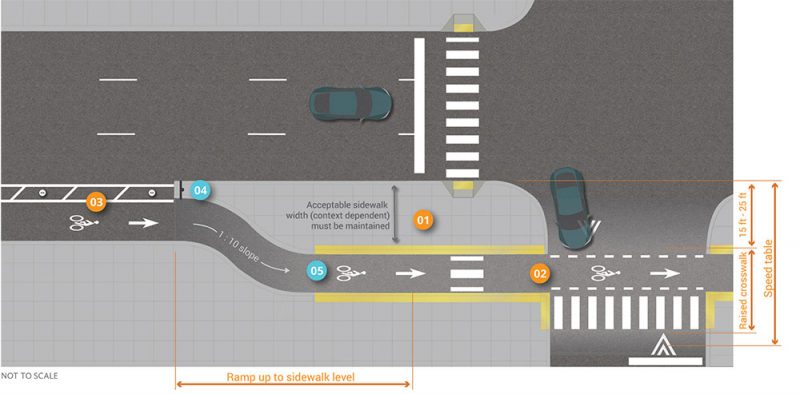

Or a proper way to step back auto parking from a parking-protected bike lane as it approaches a signalized intersection:

Or an effective way to send bike lanes behind bus and rail stops without interfering with people walking:

The guidance comes two years after the FHWA used a public memo to endorse the somewhat similar third-party design guides from NACTO and the Institute of Transportation Engineers. It’s also a few months after a different sort of milestone: as of last November, protected bike lanes are on the ground in more than half of U.S. states.

Amid so much enthusiasm for the new designs, the federal government’s decision to create a national guide makes sense, said Betsy Jacobsen, bicycle and pedestrian section manager for the Colorado Department of Transportation.

“They’re becoming more common and this reinforces that,” Jacobsen, one of the technical experts who reviewed the FHWA’s project over the course of many months, said in an interview Tuesday. “There are a lot of questions about what’s the safest way to implement them, what’s the best practice.”

The biggest winners on Tuesday, Jacobsen said, will be cities, states and other agencies that don’t yet have in-house expertise in the many nuances of protected bike design.

“I think it was really good that they jumped on it when they did and provided some direction, particularly for communities that have no idea how to approach it,” she said. “You frequently will have a local planner or engineer who may never have heard of it. It’s like, ‘What are you talking about?’ And this will help with that.”

[Editor’s Note: This article was cross-posted from PeopleForBikes.]