[Editor’s Note: This article was adapted from a guest piece for Street Roots, a newspaper that covers housing and justice issues in Portland, Oregon. It has been cross posted from People for Bikes.]

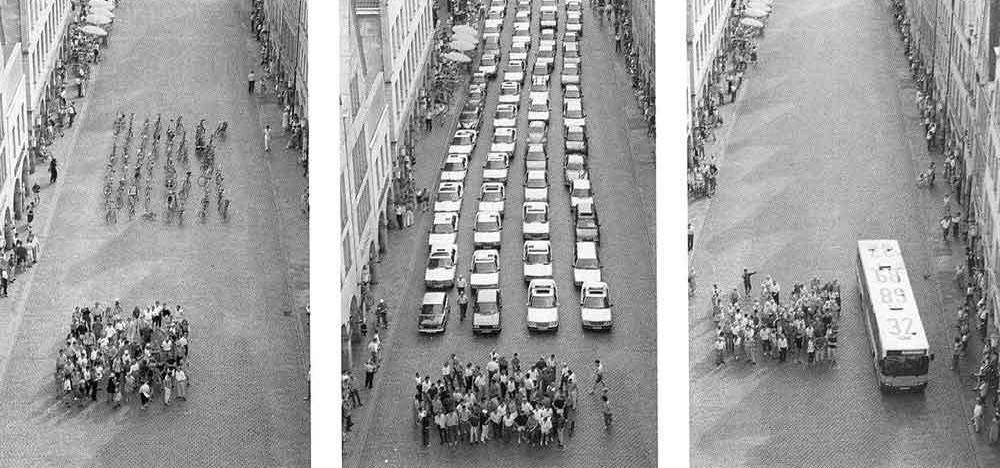

It’s one of the most famous images in modern urban planning: three simple photos showing how much city space 80 people take up when they get around by bike, by bus, and by car.

The poster was made in Muenster, Germany, in 1991. Here in Portland and around the world, it’s been used to show how you can reduce congestion by getting more people to ride bikes or mass transit. In cities, where no resource is more precious than space, that’s a powerful gift.

But keep looking at the photos and you might see another idea embedded in them, too: one about human rights.

It’s an idea that may have been best phrased by Enrique Peñalosa, who served as mayor of Bogotá, Colombia, in the early 2000s. “The first article in every constitution states that all citizens are equal before the law,” Peñalosa said. “If this is true, a bus with 80 passengers has a right to 80 times more road space than a car with one.”

Although Portland didn’t use those words when it created its downtown Transit Mall in 1977, they might be the unofficial motto for its dedicated transit lanes. There, trainfuls and busloads of people roll smoothly through rush hour even as auto congestion clogs the other streets nearby.

The rush-hour congestion was there before 1977, too. The difference today is that thousands more people are moving in and out of downtown Portland quickly—because on two of its streets, public transportation has been given the space its riders deserve.

Now, Portland is preparing to do something similar with bikes.

The spread of protected bike lanes

The idea of dedicating road space to bikes isn’t new, of course. A few California cities started painting bike lanes in the late 1960s, and today Portland has quite a few: North Williams, East Burnside, Southwest Stark, Southeast 122nd.

But what many Americans don’t know is that the first painted bike lanes were just imitations of something more substantial: protected bike lanes.

By the 1960s, some European cities started becoming alarmed at the rising price of gasoline, the danger of fast-moving traffic and the injustice of shutting off huge areas of the city—public streets—to anyone who didn’t own a car.

So, just as they’d started building sidewalks that made it comfortable to walk, they began building wide, physically separated bike lanes that made it comfortable to bike.

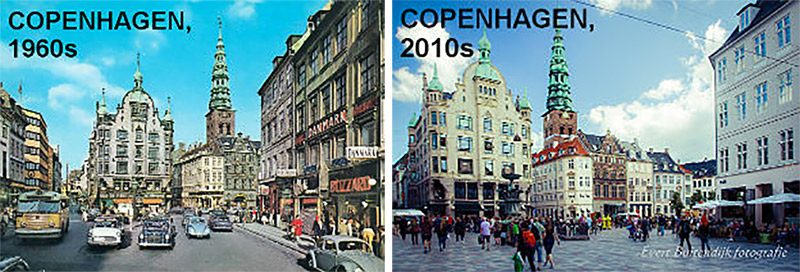

In the decades that followed, cities like Utrecht, Netherlands; Hamburg, Germany; and Copenhagen, Denmark, started taking significant space on the road and dedicating it to protected bike lanes. Raised or separated from car traffic by curbs, fences or planters, the bike lanes ran behind bus and rail stops so bike users and bus drivers didn’t have to leapfrog awkwardly with one another up the street.

The most popular protected bike lanes were built as wide as car lanes—wide enough for three friends to pedal beside one another in half the space a single car might have taken up before.

It worked. People responded to the extra street space by biking more and driving less.

But just as important as the effect on transportation has been the effect on the cities themselves. Although plenty of people still got around by car, the space dedicated to protected bike lanes made the cities cleaner, quieter, safer.

And because fewer cars were taking up space, people began finding new ways to use the spaces that came available: Socializing. Resting. Reading. Being human.

The cities hadn’t just become better places to move around. They’d become better places to be.

Gradually, people from around the world started to notice. And that’s what finally brought protected bike lanes, a few years ago, to the United States.

Rebuilding Atlanta’s social street

Armed with a big laugh and a brain full of stories, Nedra Deadwyler stands outside the little shop she owns on Auburn Avenue in central Atlanta.

The flower boxes lining Auburn’s new bike lane, separating bikes and cars for a weekend demo, are just the latest change to a street that’s seen plenty since it was promoted, a hundred years ago, as “the richest Negro street in the world.”

Then, Deadwyler explains, the 20th century tore it up.

“In the 1900s, it was among the most integrated neighborhoods in Atlanta, and then around the ’30s, the black middle class began to move over to the west side,” she says. “This became more of like, working class, lower class, poor, poverty. Just an impoverished neighborhood. And that has been the decline ever since. With the expressway, 85, coming in, it just changed the makeup of the neighborhood.”

Deadwyler knows her history for a reason. Her three-employee business, Civil Bikes, offers bike tours exploring the history of the civil rights movement that was born, in many ways, on Auburn. Down the block is the church where the Rev. Martin Luther King Sr. preached for decades and from which his son helped lead the movement. Across Auburn is the King Center that carries their work on.

But Deadwyler is just as interested in the people on Auburn today: Ethiopian immigrants, longtime locals strolling down from Wheat Street Towers, workers at the urban farm a few blocks north, and people she watches pedal past, “just kickin’ it in the hood,” as she puts it.

For Deadwyler, marking wide bike lanes on Auburn and experimenting with ways to physically separate them from auto traffic is one step toward rebuilding the Auburn of the past: one where stoops and sidewalks were places where both rich and poor could gather, relax, talk.

Deadwyler thinks a lot about space and the ways it can create the “community” the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. once spoke of.

“It’s this idea of community that does not really exist in our world anymore,” she says. “There’s a community in this shallow sense, but there are very few of these holistic, deed-centered communities.”

Rediscovering those communities will require ending the domination of cars over urban space, she says.

“It’s more than just having restaurants and bars,” Deadwyler goes on. “There needs to be more community spaces. And not just ‘community centers.’ That’s institutional, and it’s static.

“We’re learning how to change our bike lanes, how to look at our sidewalks,” she says. “Learn how to create these community spaces.”

Choices for Portland’s space

No street in Portland has the civil rights heritage of Auburn Avenue. But the battle for community space rings familiar.

From the lunchtime food cart scrum to the endless cycle of decrees for urban campers to move somewhere else, today’s downtown Portland is visibly hungry for human-friendly space. That’s true even on streets whose traffic lanes sit mostly empty for 22 hours every day, true even down the block from parking lots that empty at 5 p.m. each weekday.

But to focus only on Portland’s spatial problems is to miss the victories it’s seen so far. The food carts themselves, after all, are lined up against the edges of parking lots. A space that once held one commuter’s car might now sell the best battered fish in Portland.

And urban camping? If Portland hadn’t banned new surface parking when it created the Transit Mall, the lot that holds the Right 2 Dream Too tent settlement might have been filled with cars the day Ibrahim Mubarak and friends decided to turn it into a community on a quarter-acre.

Every square foot of Portland is precious, even though it can sometimes take decades to find its destiny.

Sometime in the next two years, thanks to a $6 million federal allocation in 2014, Portland is likely to propose its first major downtown protected bike lanes. It’s not yet clear which streets they might go on; every north-south route from Third to Broadway has been discussed.

Wherever the lanes go, they’ll kick off a battle between Portlanders who see streets only as places for cars and Portlanders who see them as public resources to divide however we choose.

That brings us back to Peñalosa, the Bogotá mayor who 15 years ago argued for his city’s space to be divvied up with more justice.

Peñalosa and his allies did exactly that. They opened the TransMilenio bus rapid transit system that, like a massive version of Portland’s Transit Mall, gave buses lanes of their own on major arterials. And they created Bogotá’s 180-mile network of ciclorutas—protected bike lanes.

Just as it had in northern Europe, reallocating urban space worked in Colombia. Bike and transit use rocketed. Citywide commute times plummeted 34 percent. Traffic fatalities fell 88 percent. A 2011 survey found that 53 percent of ciclorutas users were in the poorest third of the country by socioeconomic status.

As Portland decides how to allocate its downtown street space over the next two years, it’s likely to look to Denmark for great designs. But for great moral values, it should be looking to Colombia.

“A citizen on a $30 bicycle,” Peñalosa says, “is equally important as one in a $30,000 car.”

[Top image: Courtesy City of Muenster, Germany.]

Bus Lanes!

Louisvillians want better, faster, more diverse assortment of options to get around town. They want to talk about a more equitable and efficient dedication of public space and public resources.

This is a great graphic. I would really like to replicate it locally – maybe during a Cyclouvia? Who can provide the aerial photography? And the bus?