[Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared on the Thriving Places Project blog. It appears here with permission.]

I am a high school geography teacher. I work with students at a private school in Louisville, Kentucky. I experience something like a city through the lenses of geography: human-environment interaction, location, movement, place, and space or region. How humans go about interacting with their physical environment—either poorly (read selfishly) or well (read selflessly)—dictates my peace most of the time.

Too often I wear armor, shielding myself from realities. It is cumbersome to coerce many to live as one. The ‘many’ are just trying to make their way through a day that is often short on hours, energy, and opportunities. As a result, our cities wear the scars left by our myopic, “just trying to make it through a day.” The resulting, glaring injustices reveal how un-voted upon, shortsighted decisions mar our best intentions. There are winners and losers in any community. My bent for the liberal arts calls for me to be on the side of the losers. As it is, I ride my bike.

Spite makes me wish for a car to hit me much of the time. An accident would be a selfish affirmation, adding to my own shortsighted, holier-than-thou, immature perspective on community. And too often that’s what we’re all after, for better or worse. It’d be the culmination of so many sleepless nights taxing myself with forethought of grief. To be hit by a car and only minimally injured would prove my point—most of society doesn’t give two shits about cyclists.

They do care about the cyclist, though. It’s the value system they’re ignorant of. And so it’s ignorance that I ride towards each morning. As it is, I am a teacher.

I ride my bike out into the suburbs each morning to combat those less tangible happenings that keep us from more communal living. I’m riding my bike out towards a well heated/air-conditioned building, rolling lawns, old trees, and the upper-class. Therein I combat all that I never had a say in: racism and elitism, primarily. I ride out to confront the ignorance of teenagers with exceptional means and shiny vehicles. On a good day, no blame is shouldered for the unwanted injustices clouding our attempts at wholesome living. On those good days there is no accosting of the educators, the parents, the students or the powers that be (community decision makers). As it is, I’m part of the enterprise—community is inescapable.

That which is inescapable must be vetted. Our social constructions (something like perspective on community) when stripped of cobwebs can be enlightening; they can reveal for us where it is that we are affirming ourselves and others. Affirmation is a powerful force for goodness. Hallmarks of culture like marriage, pro-active governance, gender roles, health systems and even policing are all social constructions capable of astounding amounts of back-patting.

How can a city give affirmation? How can something like a city be the entity that proclaims:

“You’re doing great! Keep doing what you’re doing.”

The affirming city does things efficiently. The affirming city takes risks. The affirming city hears from a passionate minority. The affirming city is in league with data and not in bed with deep pockets. The affirming city puts in bike lanes and consolidates bus routes.

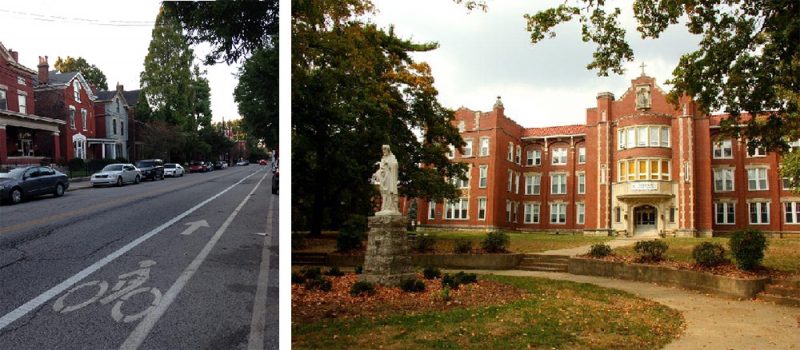

I was waiting at the corner of Grinstead and Bardstown—a crossroads between those “down there” and those “up there.” The region here is out of the floodplain, distanced from poverty and aptly named—The Highlands. There is a story and physical geography to any place.

[quote_right]One must pass through communities before community can be realized. The painting of community is more cubism or impressionism than it is realism.[/quote_right]

To ascend from Old Louisville or the West End—where race-infused riots highlight Louisville history, both new and old—up to the Highlands, one must pass through communities before community can be realized. The painting of community is more cubism or impressionism than it is realism.

The departure points are the poorest zip codes. The places left are replete with barred-window corner stores, wandering victims of lousy attempts at welfare, single mothers, and schools that resemble military fortresses. One then passes through Middle America. It is marked by pick-up trucks, local bars serving Bud Light, Hondas and homes emblematic of a past when work-ethic was all that mattered. Arriving in the suburbs is met by audible exhales—the oxygen is fuller, as is the shade offered by abundant tree canopies and multi-storied homes. Consolidated Louisville has more than one story to tell. Complexity is rampant amongst attempts at fomenting community.

On cold days I used to take the 25 bus line to that corner of Grinstead and Bardstown and would wait 12 minutes for the 55. The 55 took me up Lexington Road to the suburbs where people are pretty and cars are prettier. On the corner, where people are haggard, and on many days really cold, Transit Authority of River City (TARC) patrons don’t waste too much time searching for affirmation. We’re a sorry looking lot, the guy pissing in the corner of the bus stop says as much. Public transportation regulars are a nametag-wearing, service-industry-maintaining afterthought. But they’re together. It’s normal to notice solidarity in the lowbrow conversation at bus stops:

“Damn, it’s cold today. Dianne best be on time. I’m-a-freeze my ass off waiting for her.”

Dianne drove the 55 on the morning route. She knew my name and I knew hers. It is good to see someone that knows your name when it’s cold outside. One day, Dianne was on time like she was all other days. We were freezing our asses off. I was glad to see her and thankful for an on-time bus. (I’m certain that the city doesn’t want a whole bunch of assless, assholes standing on the corner of Grinstead and Bardstown). I was glad-er to hear her news as I flashed my flimsy transfer ticket:

“Hey Kyle, the 55 and 25 are consolidating. You won’t need no transfer ticket.”

[quote_right]The best architects are often unassuming, I’ve found. With that data—data that probably told stories of who, and when, and where, and where from—a city affirmed me and became my city.[/quote_right]

I had seen TARC employees compiling data at the corner for a few weeks. They sat in a company SUV, clipboard in hand, sipping coffee, designing a new-er community. The best architects are often unassuming, I’ve found. With that data—data that probably told stories of who, and when, and where, and where from—a city affirmed me and became my city.

Now I step on the 25 near my home at Brook and Oak and disembark on the curb outside of work. Each cold day as I signal-off the driver as she reaches for a transfer ticket I’m reminded of how this whole thing can work. I’m affirmed by my city:

“You’re doing well, son. Keep it up. We’re here for you.”

I make a point to spend those extra 24 minutes each day doing something for my students. I fail most days but I affirm myself for making a point to make an effort. A city and a person can always make a point to make an effort.

I was riding to St. Mathews, where work is, on my bike. It was hot. It was as hot as it was cold the day Dianne changed my life. Too hot for good news and affirmation, one (me) might think. I passed the corner of Grinstead and Bardstown, dipped down a small decline and started the dangerous four-laned climb towards a land where children have fathers. But on this day Grinstead no longer had four lanes; there were two driving lanes and a turning lane. Then, another small lane, about three feet wide made itself apparent.

Grinstead had a bike lane.

My city, in a joyful voice, yelled across a crowded, noisy expanse of a community:

“You’re doing good, son. Keep it up! We’ll take care of you.”

When I moved to Louisville I rode to work on busy roads for the most part. Notably, Louisville had “bike routes,” just not “bike lanes.” I took the busy roads to affirm my own selfish spite and because I was lazy—the bike routes were winding, hilly, and out-of-the-way. It was straight routes and danger for me. Adventure has to be part of my community even if stupidly so.

[quote_right]I’m taken care of and thereby free. Free to think of other things besides survival. A healthy city encourages thoughtfulness.[/quote_right]

I now have bike lanes from home to school. That glorious, solid white line protects the entire route. There are even parts with two white lines and buffer zones so that I don’t have to meet my end in the opening door of a Kia. I’m taken care of and thereby free. Free to think of other things besides survival. A healthy city encourages thoughtfulness.

That day, when the bike lane on Grinstead made itself apparent, the affirmation rung in my ears and I got emotional. I started to tear up. Without words, just by riding in a bike lane, I was thanking my city.

Just this past spring there was a place on Kentucky Street, somewhat out of my way, where data was being collected by one of those wires that counts commuters. It was laid across the bike lane. I made a point to ride over that wire each day with hopes of encouraging those brave enough to stare at spreadsheets all day. God bless them.

But what is a city? Who or what exactly was I thanking?

I was thanking the passionate folks I too often dismiss as romantics. The ones that convene for community gatherings where someone less loquacious stands and talks too long. The ones that speak for the least of these. The ones that don’t ignore a West End and single mothers. The ones that are educated enough to see the value in land and aware of how space and place make a home. The ones that don’t give-up on collective enterprises just because someone doesn’t see the vision. The ones that selflessly want the best for their city, for my city.

How can a city affirm a person? That’s a good question.

The city can wrap-up the fruits of the spirit (love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self control) in a big hug and build a bike lane. A city can look out on those freezing their asses off at a transfer point and say, “I see you. I see all of you.” A city can affirm itself by taking note of the wholeness, by making spaces for place.

I feel extraordinarily seen. Here’s to my city, a city that is collecting data. A city that is listening to the voiceless. A city that feels responsible for the shivering. A city that wants me to get to work on time and do it safely. A city that has seized the power of affirmation.

This is a lauding of my city. I’m thankful and hopeful. It’s pleasant to not have to fight on my way to curb ignorance.