“This year is going to be a critical one for the future of the city.”

Downtown Louisville sure has sprung back to life after the Recession. New businesses are popping up, construction sites are coming alive, and major developments are on the horizon. But with this flurry of activity comes the challenge of getting all the details right. It’s easy to get caught up in the zoomed-out renderings, construction cranes, and prospects of big new towers. What’s needed now more than ever is a sidewalk point of view.

That’s exactly what happened on Friday, June 19 at the Urban Design Studio when a diverse group of experts and community members convened a charrette to explore saving the old Water Company Building, currently in the way of the planned 30-story Omni Hotel & Residences’ parking garage.

But first, that quote up top is now nearly 60 years old, taken from Jane Jacob’s 1958 essay in Forbes, “Downtown is for People.” Jacobs was speaking of the mid-century trend for building mega-projects as a silver-bullet for downtown ills, but her warnings are equally applicable to today’s Omni development. “They will be clean, impressive, and monumental,” she said. “They will have all the attributes of a well-kept, dignified cemetery. And each project will look very much like the next one…no hint that here is a city with a tradition and flavor all its own.”

By now, it should be clear that this approach has failed the American city. That’s because it was clear back in the 1950s as well. “These projects will not revitalize downtown; they will deaden it,” Jacobs said in her essay. “For they work at cross-purposes to the city. They banish the street. They banish its function. They banish its variety.”

Here in Louisville, we still struggle with the notion of silver-bullet mega-projects like the Omni. In the 60 years since Jacobs’ essay, Louisville has built mega-project after mega-project, all conceived, as Jacobs put it, as “blocks,” many taking up entire city blocks with a single use. In the wake of such large-scale development, vast blocks of Louisville’s finest historic urban fabric were hauled off to the landfill. These block-sized projects replace dozens of active uses along the street with only a few. Bleak faces of parking garages and service entrances replace vibrant storefronts, creating deadening canyons and barriers to walkability. These projects look inward, where the experience is controlled and predictable.

“But the street, not the block, is the significant unit,” Jacobs cautioned. The street is what governs our experience of the city. It’s the fundamental public space and the welcome mat for visitors and residents alike. Rarely do we see the city from a bird’s-eye perspective—from an airplane or from the top of a skyscraper. It’s at the street that we form our image of the city, its quirks, its businesses, its people. How a development treats the street is among the its most important design aspects. First, do no harm.

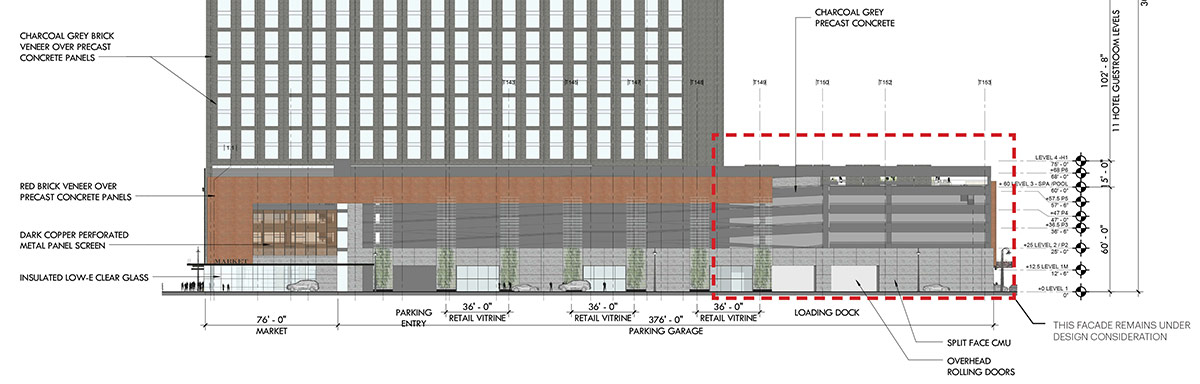

Those who do not learn from history

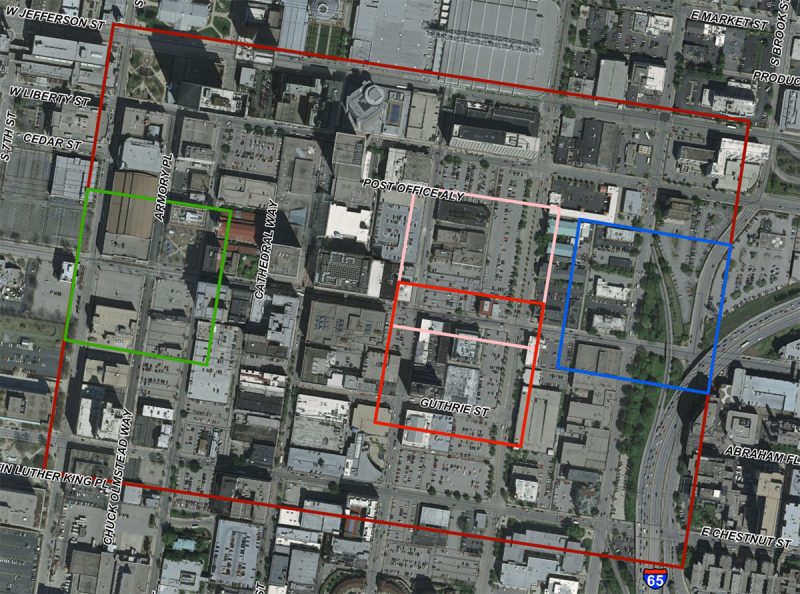

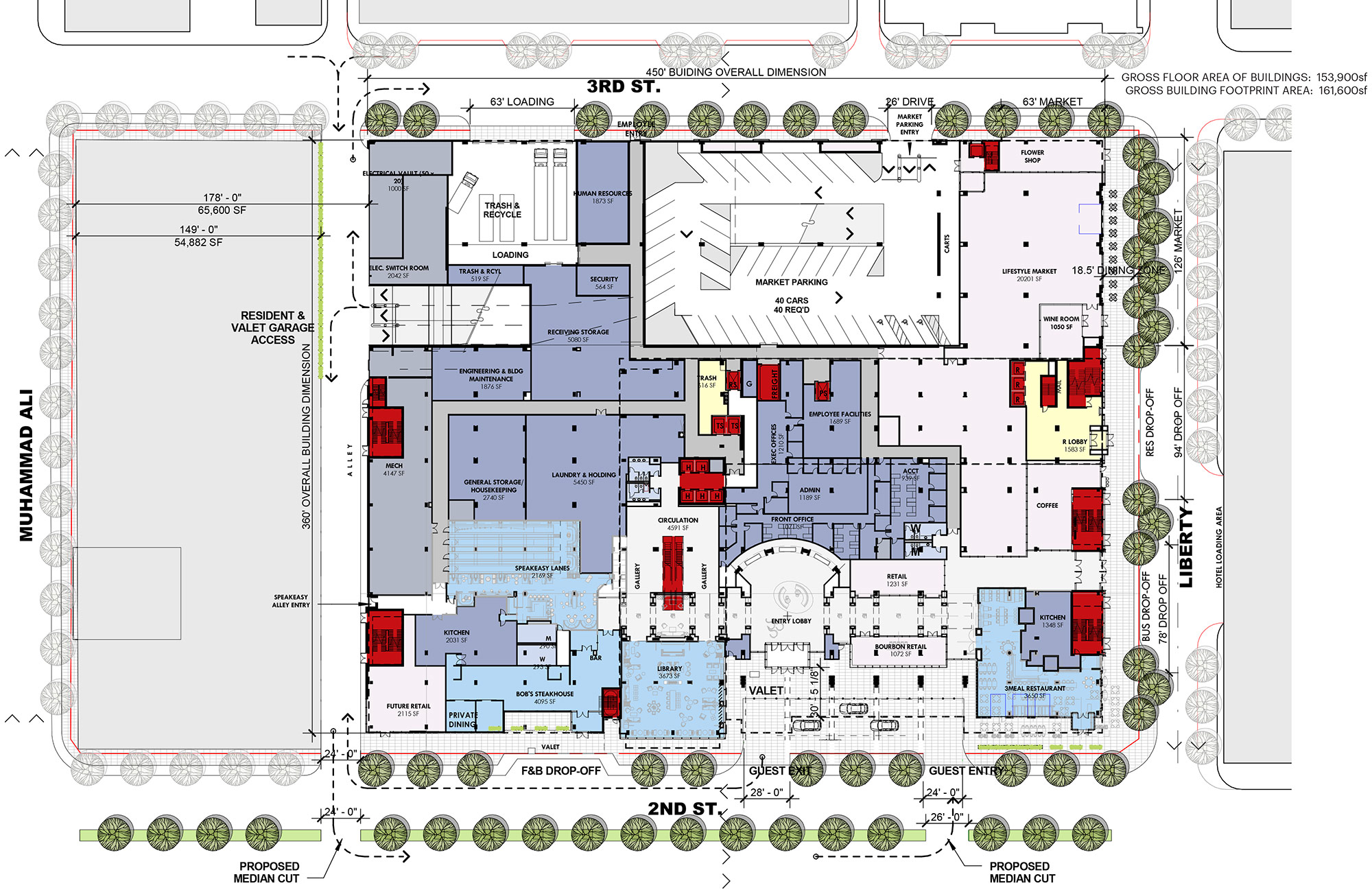

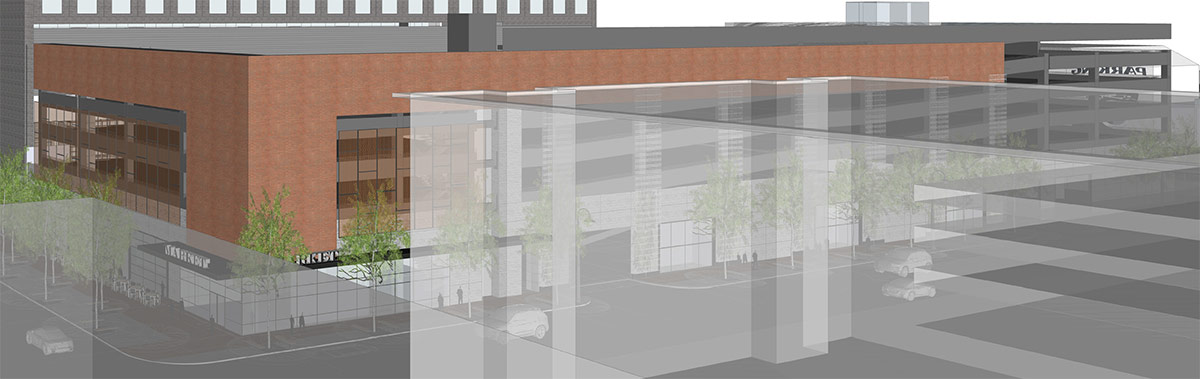

All of this knowledge is what leaves me perplexed that Louisville is still ravenously pursuing these types of projects—and at great cost to the public. Specifically, I’m talking about the proposed $289 million Omni Hotel & Residences, slated for the old Water Company Block bound by Muhammad Ali Boulevard, Third Street, Liberty Street, and Second Street. Topping out at 30 stories, with two large slabs of hotel space and luxury residences sitting atop a nondescript podium base, the out-of-town hotel designed by out-of-town architects does little to respect what makes Louisville tick—rather a deal struck between Omni and the city required a blank slate of a block be handed over for development, already wrecking two historic structures.

Yet the city and state have already pledged to hand over $139 million in public subsidy—some 48 percent of the entire project cost—to see it built. At this rate of investment, Louisville residents should be front and center at the negotiating table and the design we’ve been presented with must be altered to reflect the interests and needs of the community. Instead, city leaders have taken the tone that the community is powerless to request changes to the project.

Preservation challenges

Today, we’ve already torn down most of city’s pre-World War II urban fabric and replaced much of it with surface level parking lots, so the sting of losing entire blocks of beautiful architecture isn’t as poignant as it once might have been. Instead, we have the scraggly remnants of the city fabric haphazardly scattered in a sea of parking, which creates preservation problems of its own.

These remaining structures have withstood a barrage of natural and man-made forces that would have seen them destroyed long ago—the anti-urban forces of the 20th century urban renewal, floods, fires, and more. That legacy of survival is a testament to their cultural strength and should be a major consideration in their preservation for future generations.

A troubled history

On the Water Company Block, destruction of the urban fabric started early. Up until a couple months ago, the site contained four historic structures—all owned by Metro Louisville, and all neglected by Metro Louisville as dreams of just such a mega-project were being schemed up. First, it was the Cordish Companies’ City Center, which by comparison to today’s Omni looks downright pleasant from a pedestrian’s point of view. Next, the block might have been razed for the arena, but it’s fate is now sealed with a plan from Texas.

But decades before, the block was already in tatters. The aerial views below from 1949 and 1959 show more than half the block was already surface parking even before Sputnik. Over a century ago, however, the Water Company Block was a sleepy enclave of two-story brick townhouses. Second Street was still a narrow street before its modern widening. The lone building with a stone facade was the Water Company Headquarters (right), in a building that predates the 1910 structure we’re trying to save today. Businesses surrounding the headquarters included a saloon, stables, a bicycle repair shop, an automobile repair shop, a drugstore, and a plumber. The only building on the block predating 1910 and still standing today is the Oddfellows Hall, which is safe from demolition at the moment.

The issue of the Omni’s Louisville-friendly design and preservation of the Water Company Building stems from a contract between the city and Omni negotiated behind closed doors and prior to the requisite public review processes. That contract stipulated that the city deliver a cleared Water Company Block to Omni before construction begins.

After public outcry at the secretive economic development process and the surprise demolition of the first two historic structures, skirting public review with an emergency demolition order, Mayor Greg Fischer announced that the Oddfellows Hall structure would be saved as it does not sit in the footprint of the Phase 1 Omni plan. He also issued a 30-day window and pledged $1 million for the community to offer proposals to move and reuse part of the old Water Company Headquarters, effective May 21st.

[Reference URLs for images above courtesy UL Photo Archives – One, Two, Three.]

A charrette is called to order

To generate ideas, a charrette was convened on Friday, June 19 at the Urban Design Studio on Third Street, just a few dozen feet from the buildings in question. I was fortunate to participate in the day-long design event with some of Louisville’s top movers and shakers. Among us were philanthropists, architects, developers, community stakeholders, and representatives from the National Trust. The sense of optimism in the room was high and everyone was eager to find solutions that would help keep Louisville’s built heritage intact.

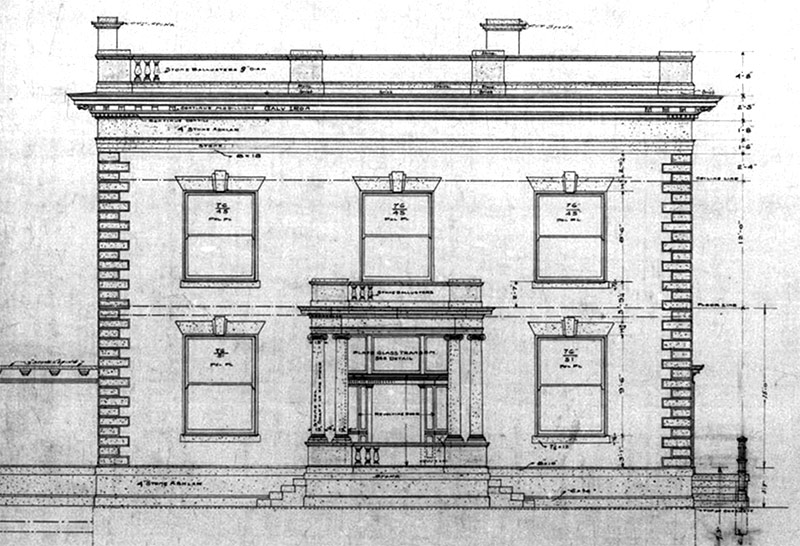

The day started with a history lesson from John Huber, former president of the Water Company. He explained the site’s early history and chronicled the company’s long history of architectural excellence, today evidenced in the Zorn Avenue pumping station and water tower dating back to the 1860s and the recently restored Crescent Hill Gatehouse. “They could have done that in a much simpler way. They could have just built a metal shed on Zorn Avenue,” Huber said. But instead they “set the standard with the National Historic Landmark we have today.”

Sebastian Zorn, for whom the street is today named, was CEO of the Water Company in 1907 and is responsible for much of the modernization of the system and construction of a new headquarters‚ completed in 1910. The building featured mahogany floors and woodwork, much of which has been removed from the building and is in storage or else has been destroyed by a leaky roof and deferred maintenance. The smaller building next door to the main structure once housed a meter shop and was built in 1912.

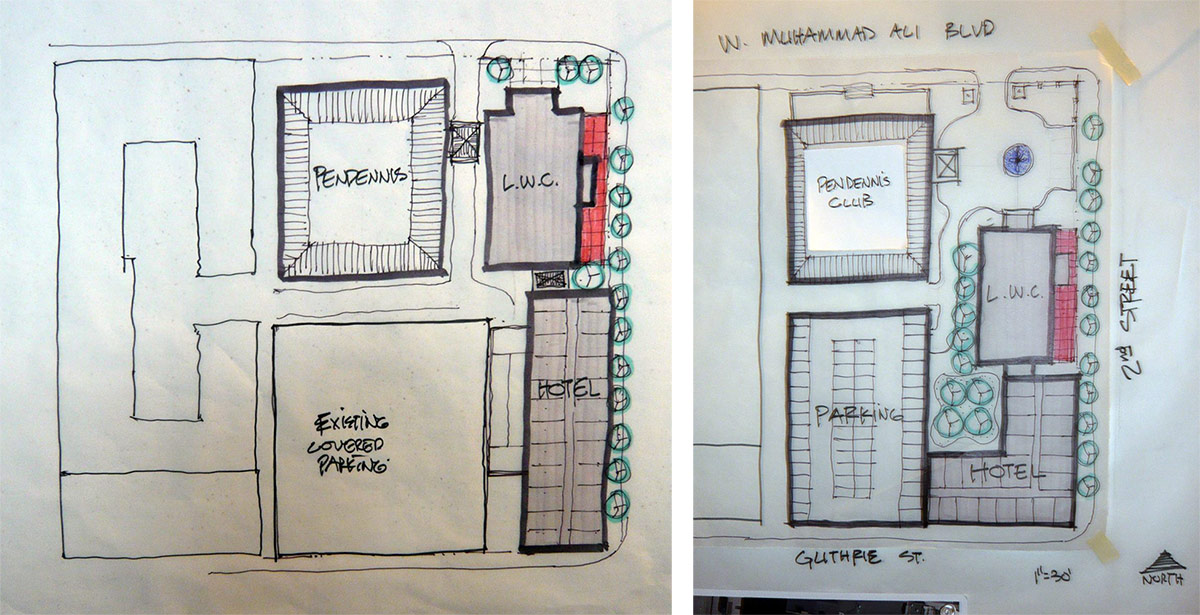

We later broke into five groups, each tackling a different design idea to save the structure. Four physical sites for a building move were identified prior to the charrette and vetted for their feasibility by organizers. Another group studied keeping the buildings in place and reworking the Omni design.

I worked with two of the groups throughout the day—one proposing to move the structure to the southeast corner of the block next to the Oddfellows Hall and focusing on keeping the buildings intact and redesigning the Omni around them.

The Oddfellows Site

The Oddfellows site consisted of an L-shaped piece of asphalt on the eastern side of the Oddfellows Hall, part of the yet-undefined Phase 2 Omni development. The concept clustered the main Water Company Building and its smaller meter shop around the hall on the corner to create a compact arrangement taking up as little of the remaining Phase II Omni site as possible while anchoring the intersection with a pedestrian-oriented cluster of buildings. This site was an attractive option as it involved the shortest move for the buildings without crossing any streets. I was also drawn to this option as clustering the Water Company and Oddfellows together created a density of historic buildings that would also bolster a case for preserving the Oddfellows down the road.

The team proposed a mix of retail and restaurants in the buildings with offices in the Oddfellows and amenities for a future Omni development in the Water Company’s second floor. A brick pedestrian alley, partially covered with a glass canopy and planted with trees would hold the arrangement together.

Preserve in place

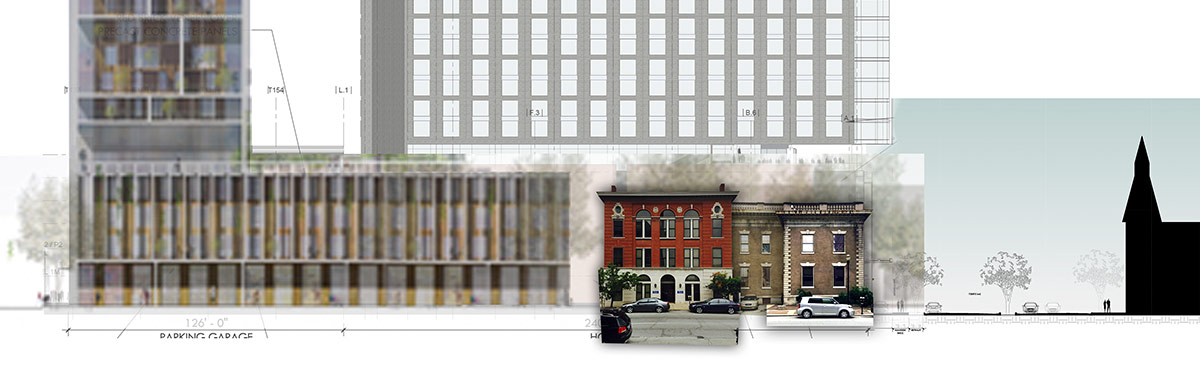

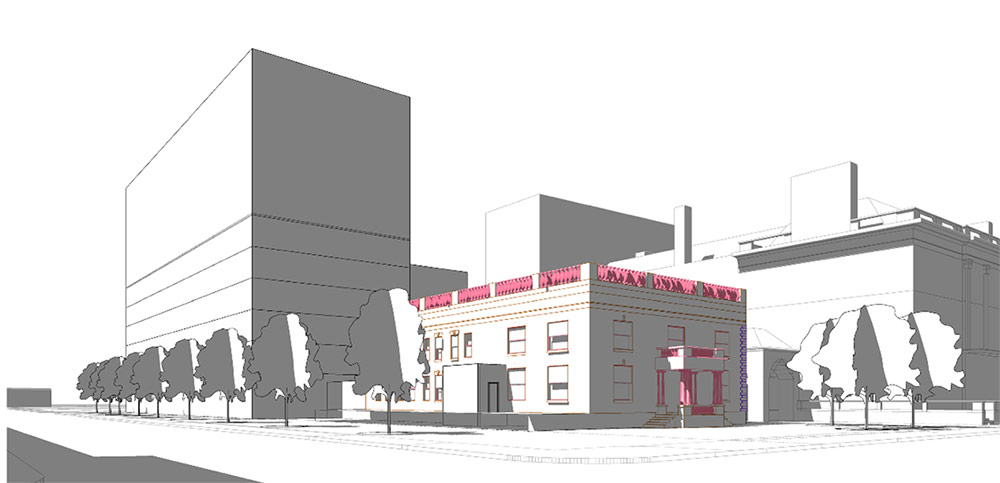

A rebel group of sorts spearheaded by charrette organizer Christy Brown pushed back at the city and Omni’s inflexibility in a site redesign by studying keeping the buildings in place. While the group began strictly looking at saving the historic buildings, the design shortcomings of the Omni plan—especially along Third Street—became apparent very quickly. The Omni was essentially going to kill Third Street as a place for people.

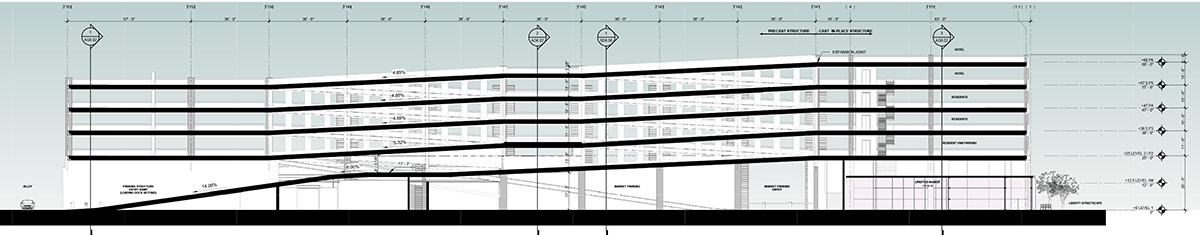

The group looked broadly at the feasibility of reorienting a massive parking structure—either underground or moving it off the street into the center of the block off the alley. While convention center hotels offer little flexibility in their internal arrangement and hence external expression, this was no easy task. A number of scenarios were explored that did manage to keep the buildings while actually freeing up new development space for Omni.

One big takeaway from this group was this if a group of concerned citizens could come up with such ideas to tweak the Omni design, then the developer’s team of trained architects could surely come up with something better. Other major points explored were increasing the health of the site with trees, light, and better walkability in general.

The Pendennis Site

Another group investigated a parking lot adjacent to the Pendennis Club on the corner of Second Street and Muhammad Ali Boulevard. This move would also be short, only crossing one street, and the Water Company’s “in the round” design—finished facades on three sides—could compliment the club. Two siting arrangements were detailed, one placing the building at the sidewalk and another behind a landscaped forecourt that would dually serve future development of a boutique hotel and guests at the Pendennis Club.

To make the move feasible with a permanent use, the group proposed a small boutique hotel atop a parking garage that would use the structure as a lobby or retail space. The group noted that a small hotel would not conflict with Omni’s contractual stipulation that the city not support any new hotels over 400 rooms in size.

First Street Site

Farther away, a leftover wedge of land pressed up against Interstate 65 at First Street and Muhammad Ali also was studied as a way to knit together the built environment shredded decades ago by highway construction. The Water Company building just fit into the oddly shaped parcel without encroaching into the right of way of the highway. While a few trees would be removed in this scheme, the group proposed planting many new ones and including green infrastructure to store and filter stormwater on site.

For economic feasibility, the group suggested the structure could be used as doctors offices to help better connect the medical district with the rest of the city. The plan would also visually and acoustically screen the highway and reduce noise pollution generated from speeding cars overhead.

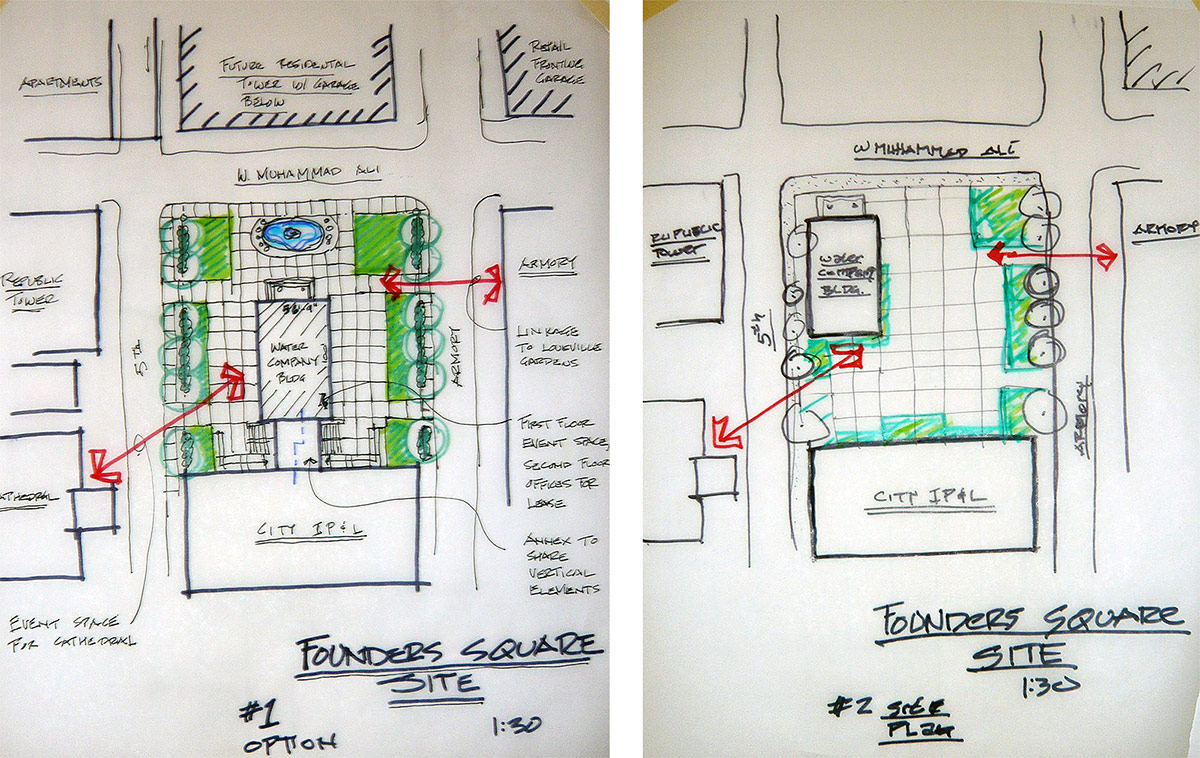

Founders Square Site

The final group studied Founders Square, adjacent to the old Louisville Armory, as a potential site for the Water Company Building. The group looked at two siting proposals. The first placed the building in the center of the underutilized green space with landscaping all around and a connection made to the Metro Development Center for expanded Metro Louisville offices. The other placed the building at the corner closest the Republic Building. Besides office use, the group suggested other public retail uses or space for events.

A community-driven plan

The findings from the Water Company Building charrette were presented to Mayor Fischer on June 20, representing hours of work from members of the community and others from abroad. The charrette was an exciting day, working with people who understand that there is both cultural and economic value in our unique legacy of historic structures. The solutions were creative and optimistic.

Here’s the full report that was compiled of all the findings:

You can read the letter sent to Mayor Fischer here and an addendum from the Preservation Green Lab here. Finally, you can read Metro Louisville’s response here.

It’s unfortunate that this charrette was necessary at all, though, as the interests expressed by the community during the event should have been part of the discussion from the very beginning. The economic development process in Louisville must become more transparent going forward if we’re going to build a city for everyone and a city that is deserving of Louisville’s history and, well, weirdness. Especially when there’s so much of our own money on the line as in the case of the Omni. Secret meetings behind closed doors and deals without public input are simply not acceptable solutions to rebuilding the core of our city.

It’s important to take the sidewalk point of view when looking at the city. The boardroom won’t build the city we want. The mega-block development won’t create a vibrant and healthy Louisville. We must learn these lessons once and for all so we don’t have to go through another Omni a decade down the line.

The whole debacle is a disgrace. Why the city is subsidizing this to the amount it is boggles my mind.

Crony capitalism? It’s possible here.