[Editor’s Note: Louisville has made some pretty amazing achievements in its first 238 years—but it’s made a few blunders along the way, too. This week, we’re launching a new contributed mini-series documenting eight of the best and eight of the worst decisions, ideas, or projects that have profoundly affected the city. This list is by no means complete—and you may have strong opinions of your own about what should be on the best or worst lists. Share your thoughts in the comments section below. Or check out the complete Best/Worst list here.]

Derby Day, 1948, was the last day of trolley operation in Louisville. What once was an extensive, thriving transportation system has now been relegated to history’s trash heap.

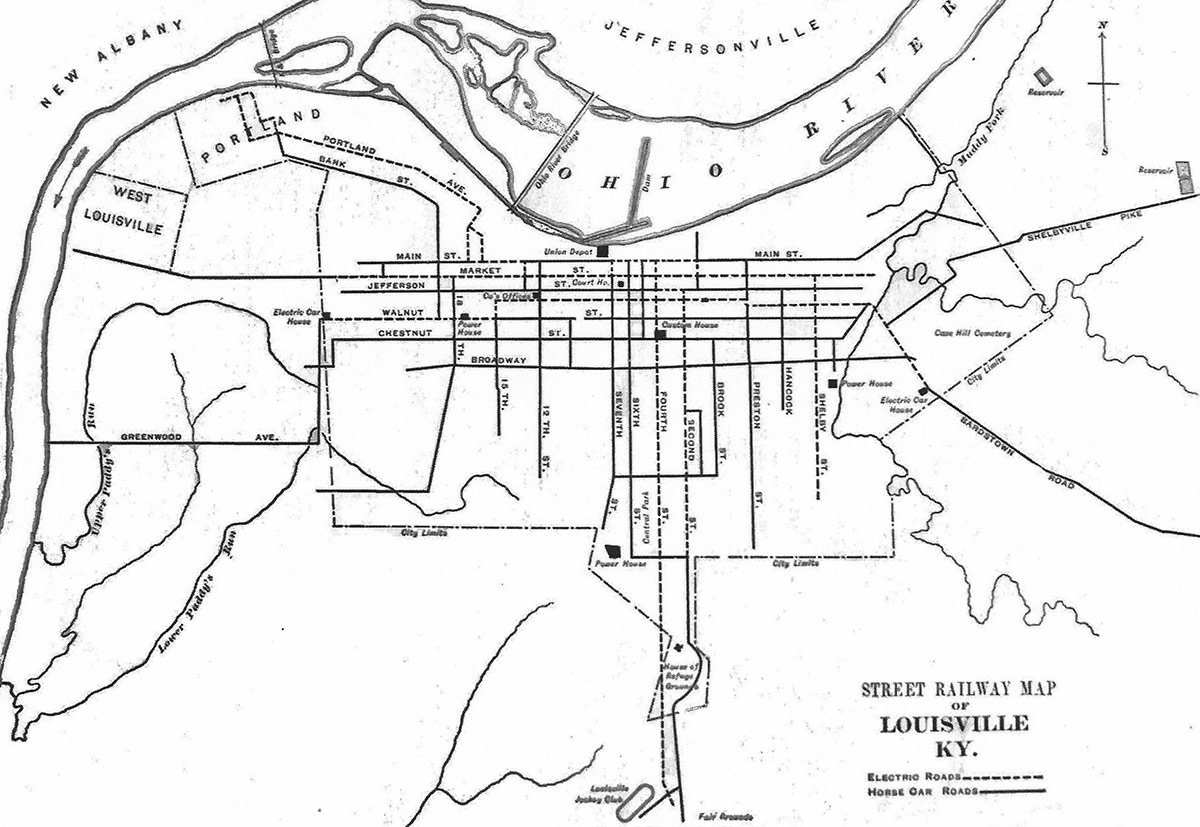

Louisville was home to a Midwest trolley empire that included St. Louis, Indianapolis, Detroit, Cleveland, and more. It was owned by the duPont family, close relatives of the famous duPonts of Wilmington, Delaware.

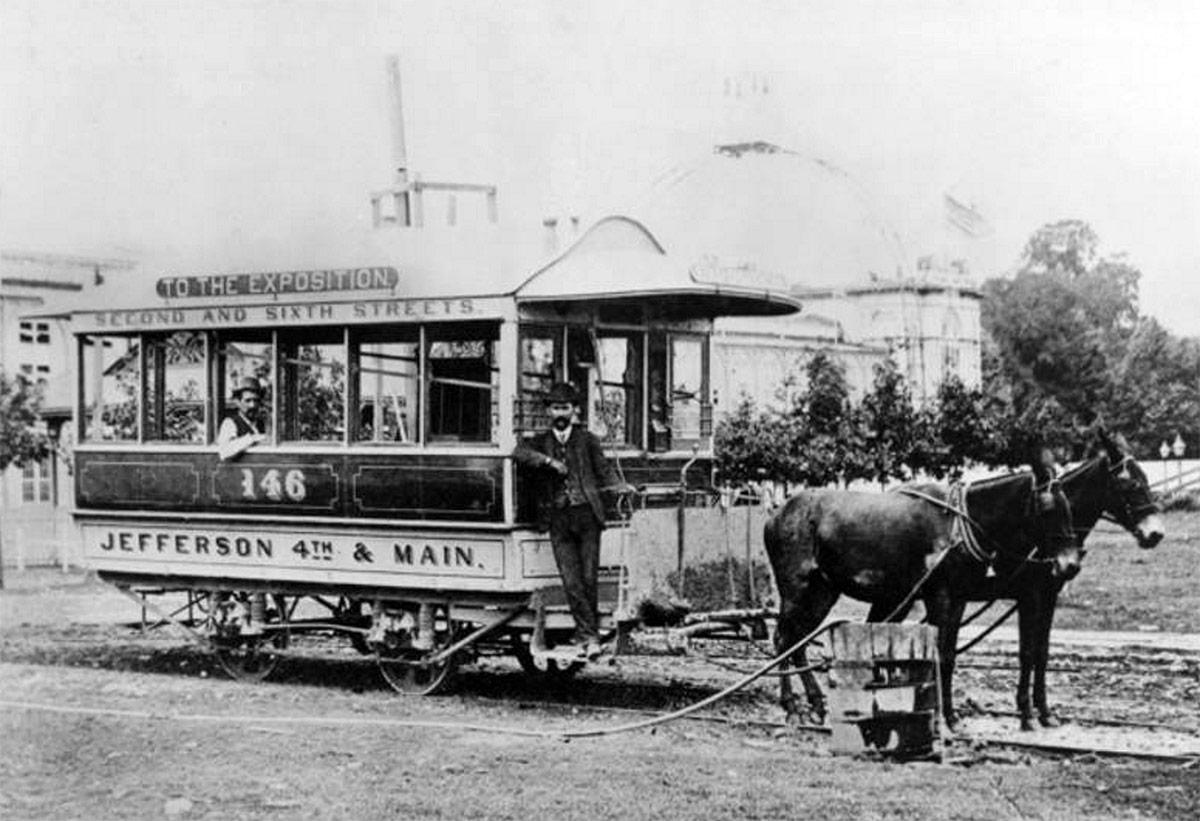

Alfred and Antoine duPont relocated to Louisville in 1854 to seek their own fame and fortune on the expanding western frontier of the United States. They invested in a variety of businesses, but their purchase of a mule-pulled trolley line in 1866 resulted in a regional network of trolley systems.

[beforeafter]

[/beforeafter]

[/beforeafter]

When the duPont Company was struggling in the early 1900s and about to be sold, it was the Louisville duPonts who came to the rescue, relocating back to Wilmington. They used their entrepreneurial skills learned here to save the family business and help create the global mega-corporation that it is today. In so doing, they sold their trolley holdings.

By the 1940s, automobiles had eroded trolley ridership to where it was no longer economically feasible to operate. There were no more trolleys running after May 1, 1948.

Fast forward seven decades. Trolleys have been supplanted by newer, similar technologies and rebranded as “streetcars” or “light rail.” Fixed-track mass transit is back in business across the country. St. Louis, Atlanta, Nashville, Denver, Kansas City, and others have viable rail transportation. Nearby Cincinnati is in the construction stages for its own.

In Louisville, there have been various studies for a light rail line, but nothing is even close to the implementation phase. Officially, the T2 light rail system proposal was investigated by TARC but is now thoroughly out of date. Most of the discussion of streetcars has come from the community. There have been proposals for a streetcar along Bardstown Road, along Market Street, and, most recently, along Fourth Street. All three of those once existed a century ago.

Instead of disbanding the entire system at once, what if Louisville had retained a select few lines that were still popular and profitable? The elevated “Daisy Line” that ran between Southern Indiana and Downtown across the K&I Bridge certainly would have had a good volume of passengers, and the east-west Market Street and north-south Fourth Street lines also would be popular today.

If Louisville had retained even a fragment of its historic system, it would have made Louisville a national leader in public transportation today.

How would even a single streetcar line or two change the city’s urban growth dynamics? Where you you like to see a rail-based streetcar or light rail line in Louisville today?

Remnants of Louisville’s trolley heydays exist just below the street asphalt surface. Paved over, these steel rails that once served the bustling network are periodically rediscovered during road repairs. They remind us today of “what if” the trolleys still existed.

[Top image of a stack of trolleys from Los Angeles at the scrapyard courtesy Wikimedia Commons.]

Agreed. Perhaps THEE worst. Whenever in New Orleans, and if ever I return to Lisboa, I look for the opportunity to ride. Philadelphia. San Francisco. Not sure if it is a symptom or rather reason for these cities being seen as ‘World Class”. But it seems we keep trotting out ideas to copy from cities like Indy or Houston and I’m always thinking “How many ‘All Expenses Paid’ vacations are given away to Houston or Indy. ZERO.

This pretty much sums it up. Sofia and Louisville are roughly the same size and the Sofians make less economically than Louisvillians, but their transit system makes Louisville look like a sleepy small town. https://sofiapublictransport.wordpress.com/

When Louisville was constructing the doomed Galleria, they were digging out tracks and putting in the motorized Trolley. Geesh!

Too bad they also trashed the interurban system that could get you out to today’s suburbs, yesterdays little rural satellite towns. That’s almost certainly a part of really making a difference in car ownership and trips. It will be hard to get people to ditch their cars if all we have is a trolley system, even if it’s excellent, in the old city, but no way to visit mom and dad in Middletown or grandma in Shelbyville. All of Europe puts America to shame, but it’s the combination of excellent local and regional transit that makes it work and keeps people out of cars.

I have read that General Motors had a big hand in dismantling the trolleys while the feds built interstates with our tax dollars, making us reliant on automobiles (and all that comes with that; everything from car insurance to fast food). It is all about creating revenue. Figure out how to make trolley systems profitable and someone will build them.

I’ve read the same thing about General Motors. If streetcar suburbs like those that surround Douglas Loop and Beechmont in the other direction were once dense enough to support streetcars, would they still not be today? Or were they never dense enough and the streetcar was just a bait-and-switch tactic the car companies knew full well would force people to drive once the streetcars failed. These places seem like they are no less dense, much of the original built environment still exists, so what changed or were the people just fooled?

My Granddad talks about what a bonehead decision that was all the time. Like stepping over a dollar to pick up a nickel. I’m sure it was expensive to maintain but it could have been scaled back and the surplus used to maintain the system for several years or at least long enough to come up with a real plan. But hey, you know what they say about hindsight. I agree with what the author suggests in terms of keeping a select few popular lines running. I don’t think it would have ever been feasible to have service to the suburbs, even today. Bottom line is that it’s hard to say that people made the choice for personal transportation over this when there was not actually a choice to make.

Trams as a technology require a large amount of resources upfront. And to justify them, one needs a huge volume of traffic to cover those huge fixed costs. Because of this by the 1920s street car lines and even some street car companies were replacing their trolley service with buses. Unless you believe GM had nothing to with this change from a less resource efficient technology, street cars, to a more resource effecient technology, automobile.

“Unless you believe GM had nothing to with this change from a less resource efficient technology, street cars, to a more resource effecient technology, automobile.” –> I mean to write “unless you believe everything from Hollywood is 100% accurate, knowing the history of street cars makes it clear GM had nothing to do with their demise.

Allen: The demise of streetcars is more complicated than just GM, as you note. There’s a great read here: http://www.vox.com/2015/5/7/8562007/streetcar-history-demise —one example is how cities insisted on keeping fares at 5¢ for years, with the result that inflation reduced the streetcar companies’ ability to fund capital improvements.

However, GM’s holding company, National City Lines, was found guilty of conspiracy in this matter. It’s on record. However, National City Lines was only involved in 46 cities. The overall trend was that the increasing number of autos kept streetcars from meeting their schedules, farebox revenue was fixed despite increases in costs, and unions often prevented the adoption of new streetcars which required only a single operator. GM, Firestone, and the other National City Lines partners only helped accelerate an existing trend. Then the government started funding freeways—but that’s its own story.

Present site of Kentucky Center for African American Heritage, including mule stable.

Schnitzelburg was the name given to the area inside the old trolley loop in Germantown (Schnitzel meaning a slice or shaving of the whole).

Trolleys were gone long before the interstates were being built. Louisville had a extra large Bus system that functioned quite well. Yes, I lived in San Francisco in the late 60’s and I loved the trolleys