For most of the 20th century, cities answered transportation problems by adding more pavement.

More freeways. More lanes. More parking lots. More things that couldn’t be reversed or revised.

So it made sense, at the time, for the public process around civil engineering projects to focus, above all else, on not making mistakes. Generations of city workers embraced the value of “Do it once and do it right.”

But today’s transportation problems are different, and so are the projects that respond to them. Naturally enough, the process of planning and designing such projects has begun changing, too.

From the experimental lawn chairs scattered across New York’s redesigned Times Square on Memorial Day 2009 to the row of plastic posts on Denver’s Arapahoe Street after a bike lane retrofit last fall, city projects are tackling big problems with solutions that are small, cheap, fast and agile. But until now, no one has created a short, practical guide for cities that want to create a program to do things like these.

Today, we’re publishing that guide.

Tools that activate the constituency for change

Researched and co-written by Jon Orcutt, policy director of the New York City Department of Transportation from 2007 to 2014, it’s built on interviews with staff in eight leading cities—Austin, Chicago, Denver, Memphis, New York, Pittsburgh, San Francisco and Seattle—to create a practical list of nine things cities need for a program that completes what we’re calling “quick-build” projects.

The street design elements here aren’t truly new; you can already find flexposts and paint in any city’s maintenance yard. What’s truly new about these projects is the process. They represent a new project delivery model, in between the familiar categories of “operations” and “capital.”

Unlike projects that must be planned only on computer screens and paper posters, quick-build projects make urban design more public, accessible and transparent by putting it on the street, responding to its uses and adjusting it in real time. They free traffic engineers from guesswork.

They activate and excite citizens who want change, instead of only those who fear it.

Some people will recognize the treatments described here as “tactical urbanism.” That’s true, but quick-build projects exist on the middle of a four-point spectrum of tactical urbanism, as described by writer and planner Mike Lydon (who offered us some guidance on this project and whose book, Tactical Urbanism, we were glad to draw on):

Here’s how our report defines quick-build projects:

- Led by a city government or other public agency.

- Installed roughly within a year of the start of planning.

- Planned with the expectation that it may undergo change after installation.

- Built using materials that allow such changes.

Within these four guideposts, there’s a broad pasture of possibility for innovative cities.

You can download a print-quality PDF of our report here. Want a nice-looking hard copy to show your boss, your community group or your favorite politician? We’ve got those too. Email PeopleForBikes Marketing Manager Aisling O’Suilleabhain with a few details about who you are and how you hope to use it: aisling@peopleforbikes.org.

All this week on the blog we’ll be publishing case studies from the report that show what does (and doesn’t) work when cities put these techniques into practice on their streets.

We wrote last year that this American traffic engineering is entering its most exciting phase in decades. The same is true of transportation planning and project management. With this report we’re honored to be highlighting the work of some of the most creative bureaucrats in the country. We’ll be even more excited to watch more and more smart bureaucrats find creative ways to adopt and adapt these principles in the years to come.

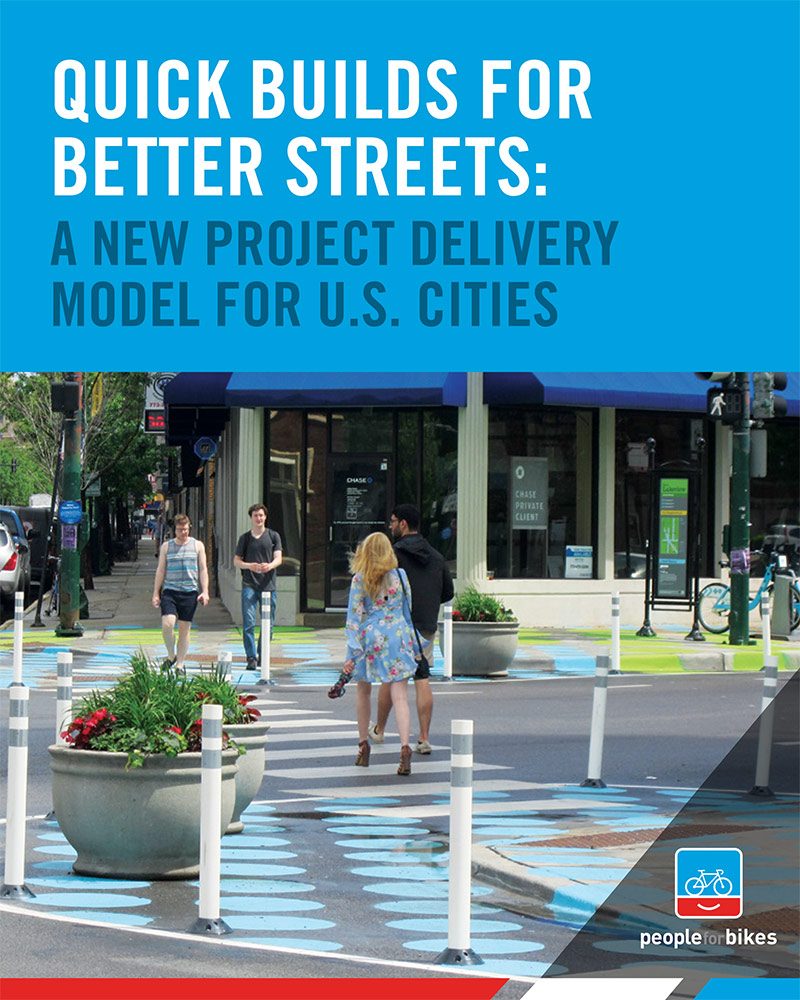

[This article was cross-posted from PeopleForBikes’s Green Lane Blog. Follow along with them on Facebook and Twitter. Top image shows Marshall Avenue and Monroe Avenue, Memphis, Tenn. Photo by John Paul Shaffer.]