In June 2015, city officials cut the ribbon on a new street in Downtown Louisville—Guthrie Street. For half a century, a half-block of Guthrie between Third Street and Fourth Street had been closed to car traffic as a pedestrian mall called Guthrie Green.

That 250-foot-long, car-free strip was the predecessor to and last vestige of the ’70s-era River City Mall that transformed Fourth Street into a landscaped pedestrian corridor. It represented the failed utopian urbanism of the mid-20th century that sought to radically reinvent downtowns across the country and to lure suburbanites away from shopping malls on the city’s fringe.

The new Guthrie Street represents the seventh remaking of the street in the past two centuries. As Louisville has grown, it has been in constant flux, but the central intersection of Fourth and Guthrie streets has seen more transformation than most. And with a proposal just submitted to rebuild the block one more time, change appears to be the only constant.

Let’s look back at the evolution of Fourth and Guthrie in its short 200-year existence. What lessons can we draw as the urban form morphs from one type to another? How does a piece or territory that’s constantly shifting affect the future of its city?

Here’s the long story.

Residential enclave

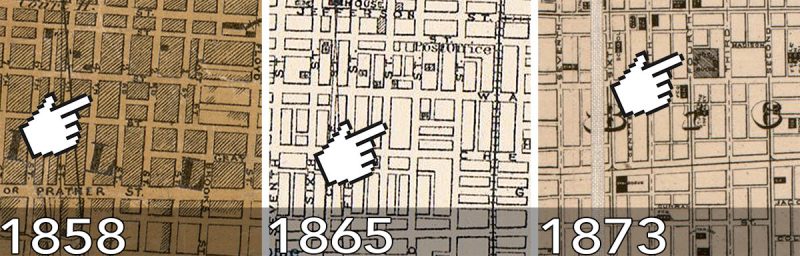

We begin our exploration of Fourth and Guthrie streets before it even exists. Before the Civil War, the area around the intersection would have been the rural edge of town. Guthrie, however, had not yet been plotted on a map and wouldn’t enter the city’s address books for decades to come. (A block east, we begin to see the street, then called Madison, noted on maps.)

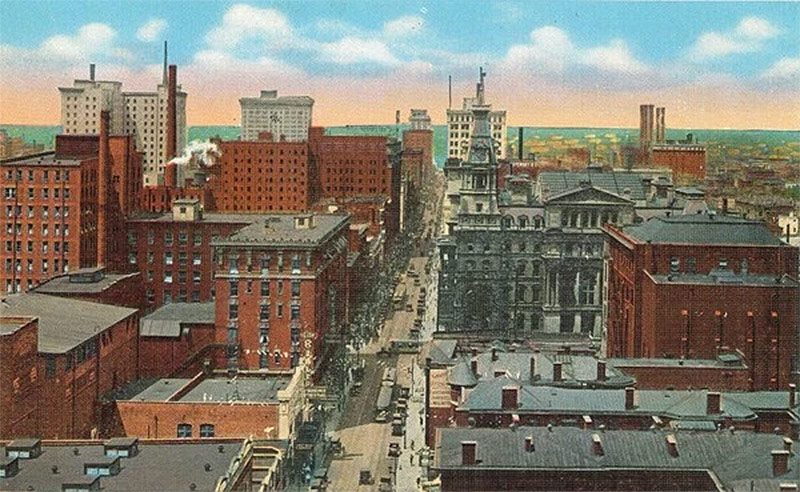

Early life in Louisville was firmly planted along the Ohio River where the city was founded. Slowly, as the city’s population crept upward, houses began to be built farther and farther south. By the 1850s, this block would have likely been a neat row of houses, many in the Italianate style popular at the time, complete with ornately detailed iron porches and detailing.

Fourth Street was home to many of the Louisville’s prominent families—Avery, Ford, Newcomb, Vogt, Brandeis—whose names can still be spotted on businesses and places around the city.

A few institutions would have also begun to emerge, including St. Joseph’s Infirmary just south of Chestnut Street in 1853 and a church on the southwest corner of Fourth and Chestnut.

After the Civil War, Louisville’s economy began to expand and the population grew rapidly. Development pushed the residential district south of Broadway and the cityscape began its first great transformation.

Louisville’s first convention center

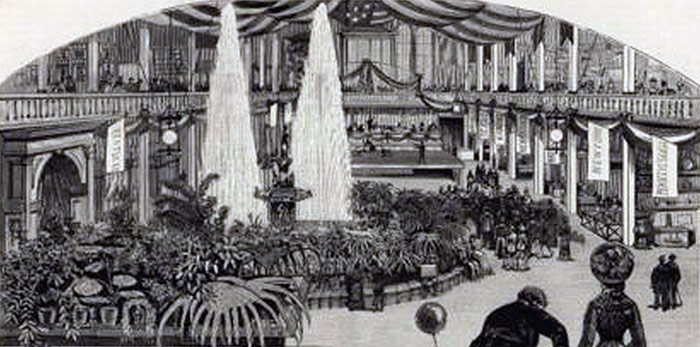

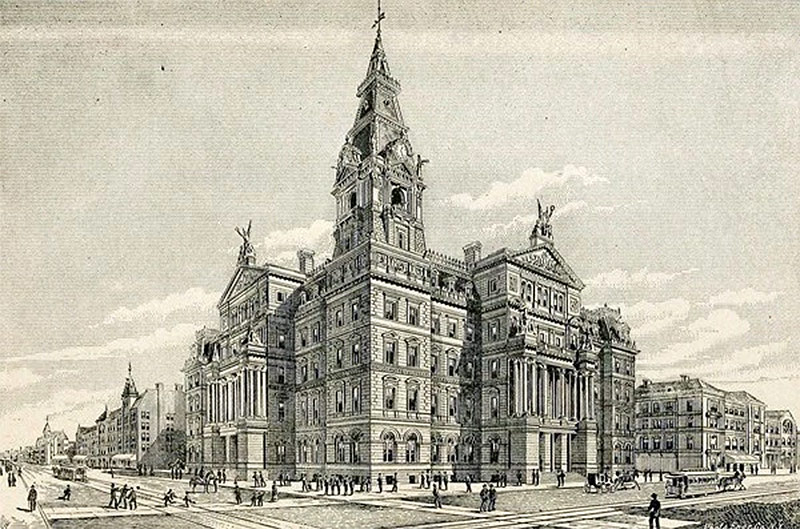

Nothing exemplified a progressing Louisville like the Industrial Exposition of 1872. With a booming economy, business leaders were eager to show off the city to residents and visitors alike. Louisville was no stranger to business and industrial shows, a sort of 19th century cross between a modern convention and a state fair, but by 18701, businessmen like Michael Muldoon and Biderman Dupont had already begun forming a much grander vision to take shape at Fourth and Guthrie streets.

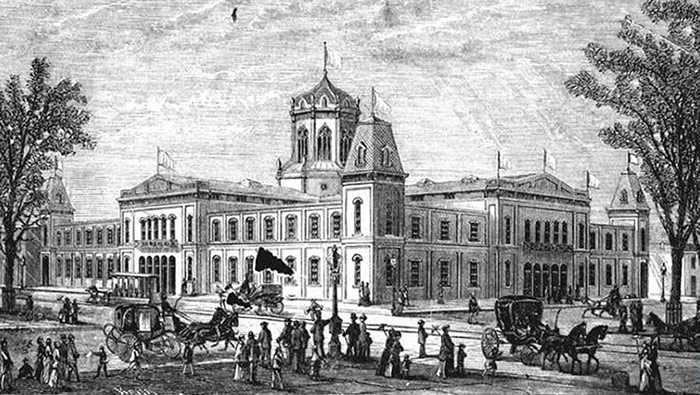

Land at Fourth and Guthrie was purchased by the exposition committee and plans for a great hall decked out in French Second Empire detailing were drawn up by architects Henry Struby & C.S. Mergell. According to the Encyclopedia of Louisville, the two-story, brick structure measured a whopping 330 feet by 230 feet, easily one of the largest structures in the city at the time.

The Louisville Industrial Exposition opened to the public on September 1, 1872. The city’s top manufacturers put their goods and machinery on display. Innovative technologies were debuted, including, according to the Encyclopedia of Louisville, a demonstration of Alexander Graham Bell’s newly invented telephone that allowed visitors to call people on the other side of the structure.

The show was also a place for citizens to experience art and culture, with galleries showing top artworks and near constant entertainment scheduled. The Industrial Exposition ran annually for a decade.

A dead-end alley and an architectural masterpiece

By the 1880s, the city was expanding at breakneck speed, and the Industrial Exposition was replaced with the much more ambitious Southern Exposition, built in today’s Old Louisville. The site was cleared, but it wouldn’t sit empty for long. The city had caught up with Fourth and Guthrie, which had become a much more central location, although still dominated by residential quarters.

It’s also around this time that maps show that one-block stretch of Madison Street change names to Guthrie, but its still decades before Fourth and Guthrie debuts on the scene.

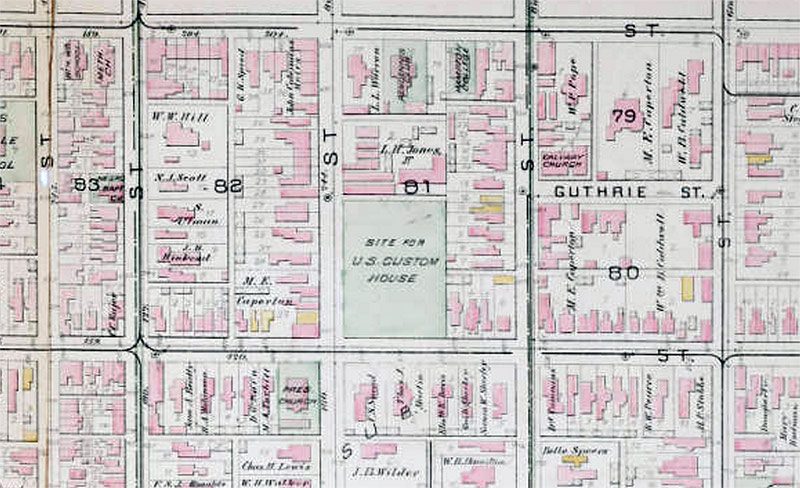

The old exposition building had become obsolete, and in enterprising Victorian fashion, was quickly torn down. By 1884, the site was marked as vacant land in city atlases, awaiting construction on an even grander scale, this time with a monumental federal building.

In less than 50 years, Fourth and Guthrie was under construction for the third time.

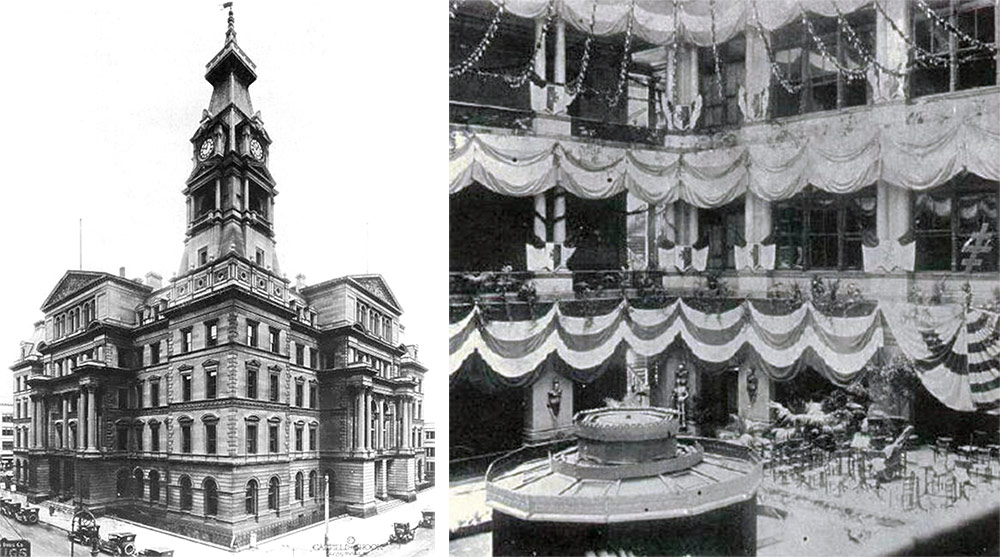

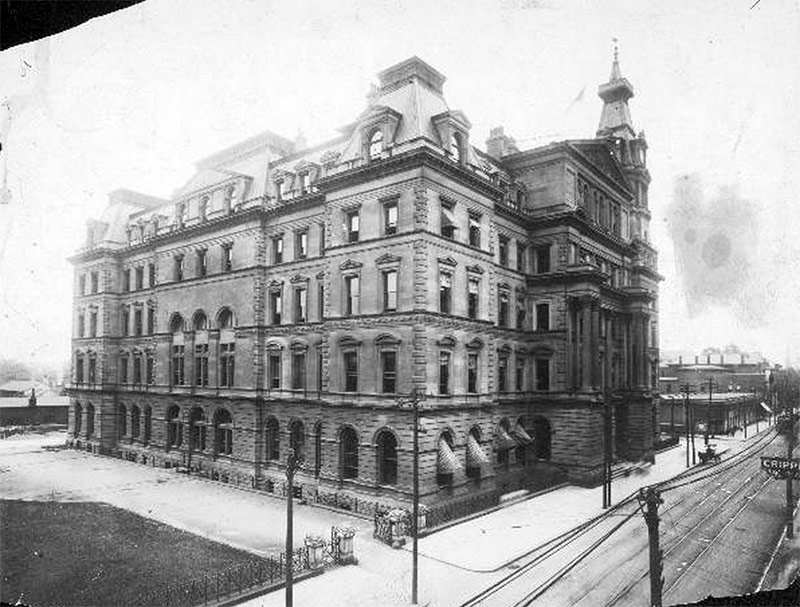

The stone edifice of the old U.S. Customs House & Post Office, designed by D.X. Murphy & Brother in the Renaissance Revival–style, was completed in 1892. The structure featured something of an architectural marvel for its day: the city’s first atrium. With its heavy demeanor, strong proportions, and towering spire, the customs house was easily one of the grandest buildings ever built in Louisville.

While the Fourth and Guthrie block was under construction, the surrounding cityscape was still dominated by residential mansions in the 1880s. It wasn’t considered anything special that houses would share a street with other uses in those days—monochromatic streetscapes are a fairly recent invention.

In the view above, you can see the corner of Fourth and Chestnut in a moment of transition, with an ivy-covered mansion still standing on the right, and the circa 1880s Guthrie–Coke Building, still standing today, now visible on the left.

The ensuing decades would be transformational times for Downtown Louisville and the old customs house would watch over it all.

Over a decade after the old Customs House was built, Guthrie Street still had not reached Fourth Street. The block-long stretch still only dangled between Second and Third, little more than an alleyway fronted by a warehouse, carriage houses, and a handful of residences.

With the Customs House, though, came the first vestige of a passage you could walk down—a narrow 15-foot-wide alley flanked by a stone wall that abruptly ended into a lumber shed.

Guthrie becomes a street

In another decade’s time, Guthrie Street finally made the leap into a real street.

“Louisville is to have a new street… thirty three feet wide, and a twelve-foot sidewalk on either side,” a March 4, 1915, article in the Courier-Journal stated (those sidewalks were later reduced to ten feet each). The street was to be built by the Speed Realty Company, which was in the process of building today’s sparkling white terracotta Speed Building. That structure opened its first phase in 1913 with a later addition in 1917.

Louisville’s Mayor John H. Buschemeyer said the street was the largest civic gesture under his administration, according to the article, noting that it “would enhance the value of property,” which the Speed company would reap by building its mixed-use structure. Even before the street was built, locals were calling it “The Speedway.”

From backlot to packed lot

The old U.S. Customs House & Post Office had one more trick up its sleeve. The enormous edifice included an open lot on its north side that planted the seeds for one of Louisville’s most urban public spaces.

In the beginning, this lot was was little more than a loading dock. It was filled with construction debris and piles of rock, separated from the alley that became Guthrie Street by a tall stone wall. After Guthrie Street was built, the space would take on a new significance.

But first, a competitive interlude.

Rivalry among Louisville’s retail districts was high in the early 20th century when the Downtown was a thriving shopping scene. This area of Fourth Street stood at the heart of it all. An article titled “Electric Sign as Business Getter” in the January 2, 1915 issue of Electrical Review, described how “one mercantile district invades another,” in this case with an enormous electric sign erected at the foot of today’s Guthrie Street:

The Market Street Improvement Association has gone into Fourth Street with a big sign in an effort to divert trade from that thoroughfare to the other. The plan… provided for displaying on the big board of the Federal Sign System the slogan, “It pays to buy on Market Street.” This is the trade-getting motto which has been adopted all up and down Market Street.

The sign, they said, was “exceedingly conspicuous.”

Also apparent with the opening of Guthrie Street was that the Customs House backlot began to be known as Lincoln Park, “a small breathing space next to the Government Building.”

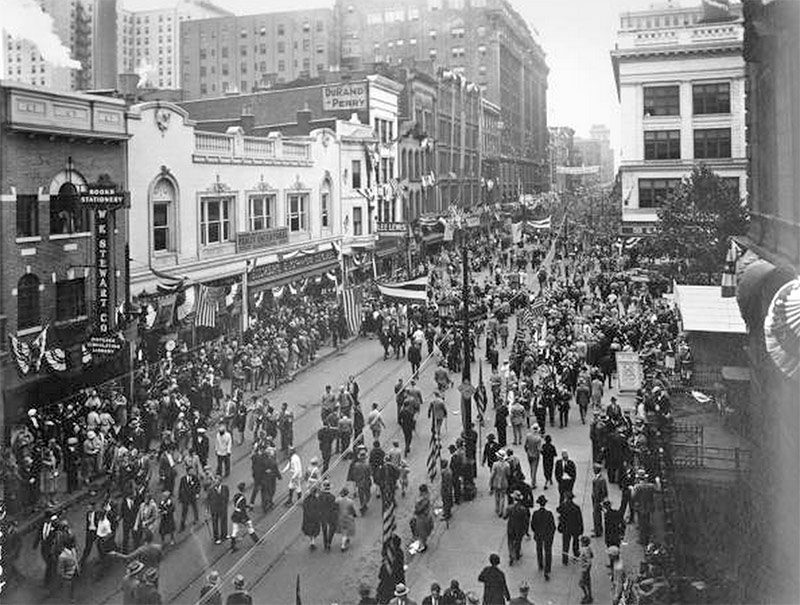

Little Lincoln Park, measuring just 82 feet along Fourth Street and extending 230 feet down Guthrie, was a fixture of Louisville civic life in the early 20th century. On November 7, 1923, and undoubtedly many other election cycles, throngs filled the park to hear the Courier-Journal‘s voting returns.

That year, an estimated 15,000 people crowded Lincoln Park, “the largest crowd that ever gathered to get election returns in Louisville,” according to the newspaper. A high-tech “telautograph,” “best… described as a glorified stereopticon machine” projected the results onto the side of the Customs House. That night’s big win was William J. Fields‘ re-election to the U.S. House of Representatives.

The crowd overflowed Lincoln Park, filling the new Guthrie Street solid. “A corps of policemen labored incessently [sic] to maintain a narrow traffic lane for automobiles and street cars on Fourth Street, although traffic was blocked time after time.”

Lincoln Park and Guthrie Street were host to a number of important Louisville events, including the Pogo Stick Jumping Contest of 1922. “Guthrie Street, between Third and Fourth Streets, at noon yesterday turned into a bouncing sea of boys and girls, each outdoing the other trying to win the $10 prize that William Mahoney, vaudeville actor at B.F. Keith’s Mary Anderson Theater, had offered for the best pogo trick,” a March 19, 1922, Courier-Journal article said. That prize would be closer to $150 today, and was shared by Miss Pauline Buford, 11, of South First Street, and Peter Moller, 12, of West Market Street.

Making a spot of beauty

In 1934, plans were drawn up by the Junior Board of Trade to redesign Lincoln Park into a “Beauty Spot,” according to a December 23 article in the Courier-Journal. Landscape architect Carl Berg, chairman of the board’s civics committee, created the pictured rendering of the updated park with a low brick wall capped by stone and a light fixture. A hedge mixed with stone benches would add to the streetscape. A concrete bandstand with a prominent dome had been previously built on the site.

“The Junior Board of Trade has announced plans to transform bleak Lincoln Park into a garden of inviting beauty,” the article read. “A civic eyesore for years, this open space in the heart of downtown Louisville has deteriorated apace with the deserted old Postoffice Building that shadows it on the south side.”

“The plans were drawn with the view of converting the entire area into a park if and when the old Postoffice Building is town down,” the article continued. “Efforts then would be made to move the heroic statue of Lincoln from the library lawn to a site of prominence inside the park that bears his name.”

A prospectus describing the project from the Junior Board characterized the old park as “a catch-all for cheap amusements, advertising [ahem, Market Street billboard], a hangout for vagrants, and anything but a beauty spot in the downtown district.”

A monumental mistake

Just as this Customs House replaced its counterpart at Third and Liberty streets from 1858, another federal building replaced the grand Fourth Street structure. The new customs house still stands today in elegant Beaux Arts style on Broadway between Sixth and Seventh streets, responding to a time when Broadway was considered the center of town.

Louisville, like most places, has had a preoccupation with style over its history. As new architectural preoccupations emerge, a 40-year blind spot urges us to tear down the previous generation’s buildings. Forty years is too young to be historic but too old to be cutting edge. It’s the most dangerous time for any architecture.

At Fourth and Guthrie and around Downtown, Italianate gave way to French Second Empire, which was replaced with Renaissance Revival, which then went Beaux Arts, followed by Brutalist, and then Postmodern, and who knows what next. If a structure makes it past 40, society tends to open its eyes and appreciate it again. We’d do well to wonder what we’ll miss a decade from now of what we’re throwing away today.

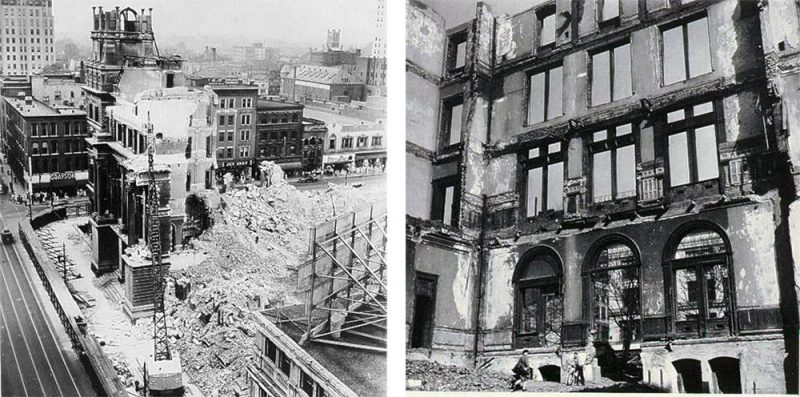

With the new Gene Snyder Courthouse up and running on Broadway in 1932, the old Customs House was abandoned. It stood vacant and looming over Fourth Street for a decade—derided as a pigeon stoop. And certainly this structure would have taken on an ominous tone with its soot-covered stones dripping with grime and a deferred maintenance from the Great Depression.

Proposals for the structure’s adaptive reuse as a cultural center or museum failed and the building was demolished in 1943, only 50 years after it opened. What should have been Louisville’s “Penn Station Moment” transpired two decades too early and was largely forgotten.

Fourth and Guthrie was ready to be rebuilt a fourth time.

A park in its place

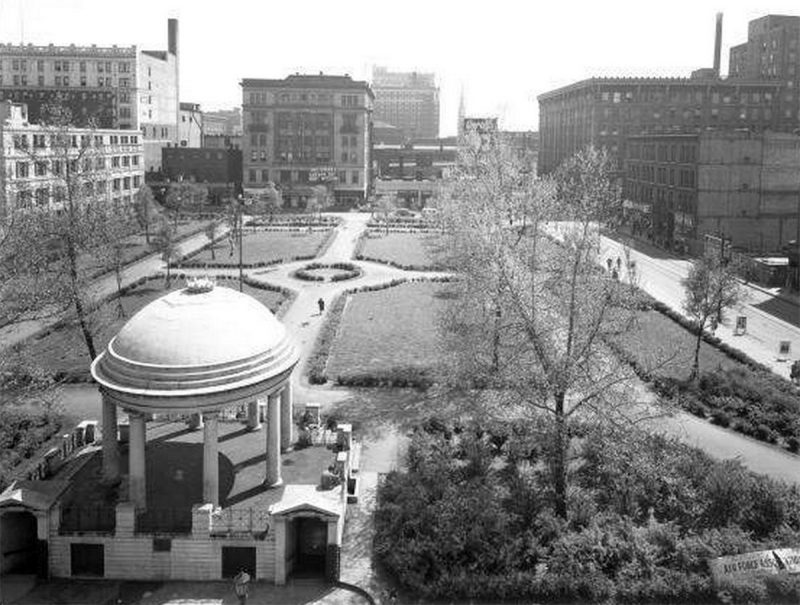

With the site cleared, Lincoln Park was able to spill out from its small site and stretch all the way down to Chestnut Street. The expanded park was dedicated on Monday, May 8, 1944 with Mayor Wilson W. Wyatt presiding. Louisville Male High School ROTC Band paraded.

With the Customs House gone, the domed concrete bandstand was now flooded with sunlight. The tiny structure gave architectural focus to the green space. And for a short time, the simply arranged Lincoln Park took on the role of a real urban square.

The trees on the northern edge of the park were fairly mature, having stood for years in the small Lincoln Park space behind the Customs House. Newer trees planted in the south looked spindly in comparison.

Lincoln Park featured a formal arrangement of paths typical of many much older parks in other cities, such as Washington Square in New York. Hedgerows lined a radiating pattern of pathways, defining a border between the walk and lawn.

There was nothing particularly notable about the detailing or design of the strolling park other than it was an economical layout that would have provided a peaceful focus to the center of a bustling city’s prime retail district. There were enough remaining notable buildings to form a proper urban edge around the park that gave it a real sense of being a town square.

Mayor Wyatt said he wanted to make the park a permanent fixture in Downtown and was working with the federal government, which owned the site, to acquire the land. But there was powerful business opposition to the park.

Banker A.J. Stewart wanted the site developed, according to an article by Courier-Journal urban affairs correspondent and noted urbanist Grady Clay. Stewart authored a 1943 survey for the Urban Land Institute and a small booklet titled “Proposals for Downtown Louisville” calling for selling off the land and buying cheaper land elsewhere for a “larger and more scenic park.” He had entirely missed what an urban Lincoln Park represents for a city.

Mayor Wyatt was succeeded in 1946 by Mayor E. Leland Taylor, and the park battle continued. A concept for an underground parking garage with a park on top was floated, but it was too late. No deal was reached and the land was slated for auction. Clay noted, sounding somewhat dissatisfied, that “the city had tried to ‘save Lincoln Park’ time and again,” without success.

In 1946, three years after the Customs House was torn down, the feds auctioned the land to a group of land speculators from New York and New Jersey. The high bid was $1.8 million for the two-acre park. “I was amazed that local people didn’t bid the price up to what the property was worth,” lead investor Jules Endler told Clay. “Up this way, that sort of land wouldn’t have sat around vacant for five minutes. I’ve studied cities all over the country, and I never ran into anything like that.”

Various proposals included a skyscraper and several other development schemes, none of which materialized. The University of Louisville also explored building a major development there. By 1950, the speculators had flipped the land, achieving what Clay describes as “one of the most successful deals in the history of Louisville.” Three parcels were sold for a quick profit of $800,000—or around $8 million today.

Like its predecessor, the larger Lincoln Park began to attract the blight of advertising. Public space in Louisville, it seems, was required to turn a profit. By the late 1940s, billboards began popping up in the park and even a model suburban house by construction company M. Shapiro & Sons advertised “Washington Park Homes.” Louisville’s grand urban park was being used to hock suburban housing, which looked gaudily out of place against Downtown’s large buildings.

Lincoln Park and its bandstand lasted only a short while longer. It was cleared in 1950 to become the site for J.C. Penney’s and W.T. Grant’s department stores.

Let’s move on to Fourth and Guthrie reconstruction number five.

A new block of retail

Construction on a new three-story J.C. Penney building—the first in Louisville and the 22nd such store in Kentucky—began early in 1951. The concrete structure, clad in large plate glass along the sidewalk and windowless light beige brick above, would cost around $2 million and cover 76,000 square feet.

The building was designed by C. Battaglia of New Jersey; R.I. Hillier of New York; Herman T. Suedkamp, New York; and J.H. Bliss, Florida. The design included a horizontal canopy winding down from its prominent vertical marquis and wrapping around the structure. The canopy was pierced by series of circular openings that admitted light. A semicircular glass display window anchored the corner, showing nativity scenes in the winter.

Near the radiused corner, itself emblazoned with another J.C. Penney sign, a large flagpole was anchored into a series of contrasting brick-lined bas reliefs.

Grady Clay reported in winter 1952 that construction Downtown had come to a near halt, with the exception of the J.C. Penney’s project. It represented “Louisville’s first major new ‘main-stem’ store in more than 30 years.” (The Main Stem is a term used to describe Manhattan’s Theater District, but it’s unclear what it means in Louisville. Perhaps the same thing.)

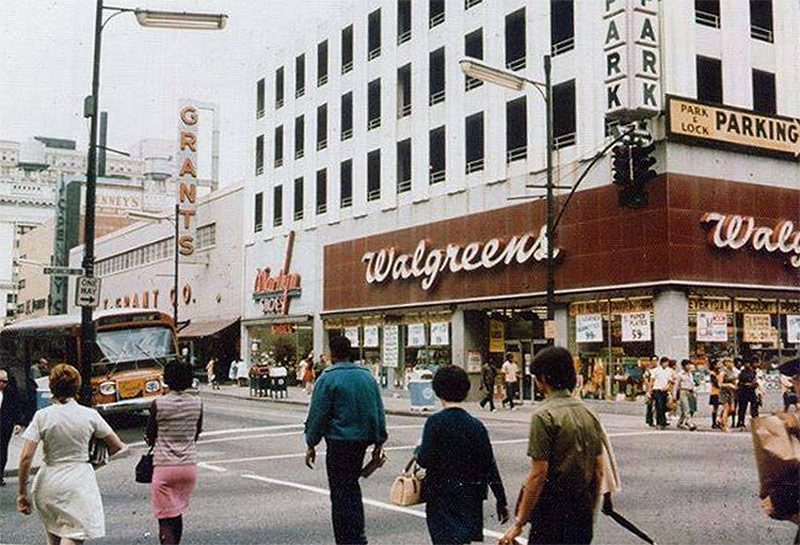

When the store opened on May 15, 1952, the J.C. Penney building stood alone on the block next to a large surface parking lot. Soon, a W.T. Grant’s and parking garage would appear by its side.

In spring 1953, W.T. Grant Co. purchased the middle parcel for another department store. The company already had a store in the area two blocks north between Liberty Street and Muhammad Ali Boulevard (then Walnut Street).

The two-story W.T. Grant Co. building was completed in early 1955, but didn’t officially open until the spring. It would cost $1 million.

The parking garage at Fourth and Chestnut would take a little longer. The site remained a surface level parking lot until 1960. Construction began in February of that year on the five-story, 340-car garage, developed by a group from Chicago. A Courier-Journal article at the time generously called the garage “a vote of confidence” in the city’s future.

Plans called for a Walgreens anchoring the base of the garage, joining two other retail stores. Initial plans proposed adding additional floors later to house a motel or offices. The structure was designed by Fred Brauning & Associates Architects of Detroit.

By 1962, Walgreen’s and Dan Cohen Shoes had located in the base of the parking garage. Then, the garage was covered in vertical panels that gave the structure the more traditional appearance of having windows.

Architecturally, the corner had nosedived since the old Customs House was torn down. By 1970, the transformation was complete as Louisville’s once grand Fourth Street puttered along in ho-hum blandness.

Architecture as billboard

Before we move on, it’s worth taking a look at the stylistic quirks of the mid-century urban department store represented by the J.C. Penney building and Grants. Throughout the 20th century, it’s easy to observe the streamlining of architectural detailing into Art Deco and then Streamline Moderne. These styles represented the dawn of the machine and automobile age when sleek represented cutting edge.

But by the middle of the century, even those details shown through as trappings of the past. With a little help from another new technology—air conditioning—department stores such as J.C. Penney’s managed to strip off even more, leaving nothing but a windowless expanse of smooth brick, perhaps with a contoured corner. The same carbon copy buildings began to appear across the country.

Giant lettering and a blank facade made for a very graphic brand image. And as car culture continued to expand, the easy-to-read-at-high-speed-travel design of highway stores also began to inform the architecture. The building had been essentially reduced to a billboard.

The pedestrian mall itch

The concept for creating a pedestrian mall in Louisville was thought up by Yale urban planning graduate student Dieter Hammerschlag in 1955. He had been studying Louisville for his thesis and concocted a radically ambitious plan to remake dozens of blocks of Downtown as a pedestrian utopia free of cars. He called it the “H Plan.” (The first talk of a mall dates to discussions in 1943 by Mayor Wilson Wyatt, Sr., and businessmen at the time, but those plans led nowhere.)

The city put up $250 to bring Hammerschlag to town to show off his ideas—he had already won over the imagination of Grady Clay, who became a champion of the concept. While in Louisville, Hammerschlag presented his thesis on television alongside Mayor Andrew Broaddus, University of Louisville Professor Walter L. Creese, Planning & Zoning Commission Director William L. Watts, and Charles W. Welch, Jr., from the Louisville Chamber of Commerce’s development committee. The plan was also exhibited around Louisville.

While the show was simply about some creative student work, the weight the city and Clay’s writing in the paper threw behind it gave it distinctly more gravitas. Clay praised the plan for its “imagination, plus a strong emphasis on beauty,” something he said regular reports out of Louisville lacked. Clay and others wrote about Hammerschlag dozens of times over the next two decades until the River City Mall was achieved that he became something of a household name, even referenced in an advertisement for a furniture store.

At the core of Hammerschlag’s urban utopia was a pedestrian mall running along Fourth Street from Liberty Street to nearly Broadway. The top goal of the plan, according to Hammerschlag, was “to make Fourth Street an island for safe and pleasant pedestrian circulation.”

To make the pedestrian mall work, the city would have to be remade from the top down. Alleys on either side of Fourth would be widened to allow truck traffic and deliveries. Guthrie Street would also be pedestrianized and extended through a storefront to Fifth Street. Four prominent bus stops were located on Third and Fifth and infilled commercial development in parking lots to create a dense “compact zone.” Finally, the whole area would be circled by a ring of parking garages—a lot of parking garages. Seriously, almost a dozen entire blocks converted to parking garages. The H Plan was a mega-project for the history books.

Most business and property owners remained politely skeptical of the proposal, but Louisville’s top urban thinkers now had an innovative project to champion. And they would nearly nonstop for the next two decades.

An experiment in tactical urbanism

In 1960, Louisville embarked on an experiment that resembles the most innovative trends in placemaking today: Tactical Urbanism. The idea is one in which temporary changes are made to a place to test out how it looks, feels, or operates. If they don’t work out, they can be tweaked or removed. We see it today in Park(ing) Day where small parks are built in parking spaces or in the Better Block movement, where a block or more of street is remade with plazas or traffic calming devices.

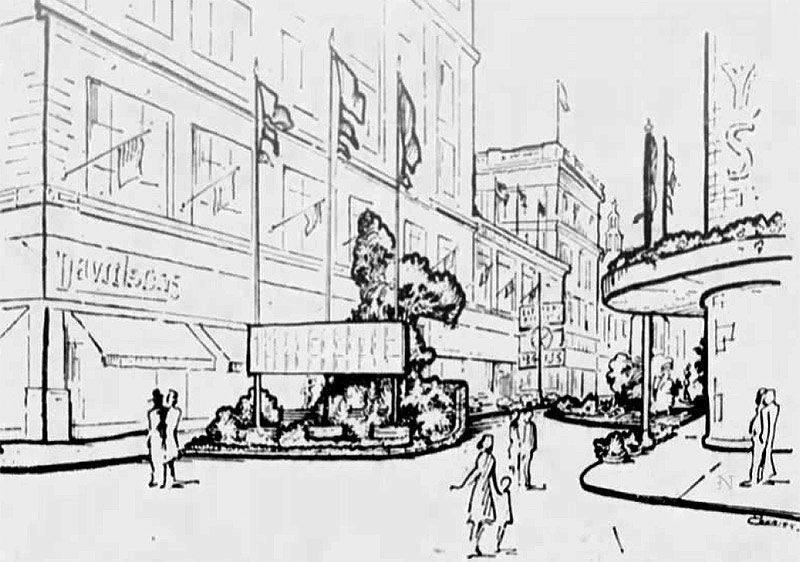

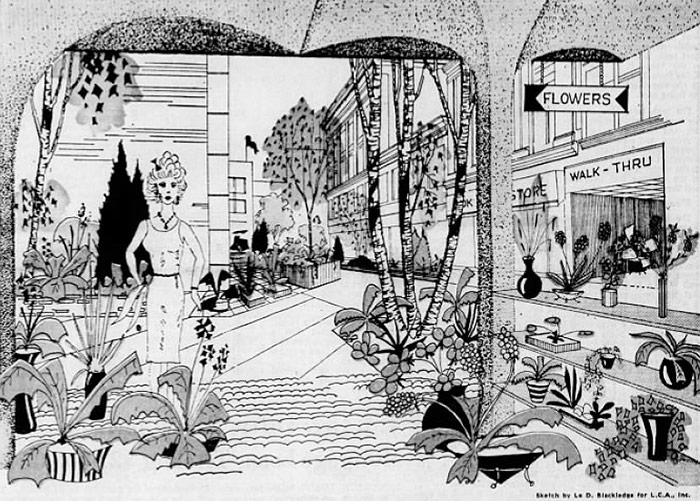

That May 16, Louisville shut down Guthrie Street to drivers and installed a temporary pedestrian plaza comprised of flower pots, trees, pools of water, a sidewalk cafe, and lots of art. During the intervention, the name of the street was changed to Guthrie Green.

The effort was spearheaded by Philip E. Giessal, executive director of the planning group Louisville Central Area (LCA) and the Beautification League as part of an annual Clean-Up Campaign. Architects Arnold M. Judd and E.J. Schickli, Jr., and landscape architect Campbell Miller drew up plans for seven planted beds lining the block. The overall scheme, however, is credited to a 28-year-old landscape architect from Iowa State University named Le (one “e”) Blackledge, according to Grady Clay. Some 20 groups and the City of Louisville were involved.

For two weeks, pedestrians were invited to stroll along a lush, car-free expanse. A cafe was set up in the middle of the block for al fresco dining. A fashion show and art exhibits were scheduled. Specially designed lighting made the plaza glow at night and hidden speakers added to the Green in a way city streets simply couldn’t perform.

Grady Clay called it a “pedestrian paradise.” “Above all,” Clay wrote, “the Green will provide the first complete change in atmosphere on a downtown Louisville street.”

Louisville in 1960 would have still been a fundamentally urban place, although cultural norms were shifting toward the suburbs and the automobile. Everyone would have shopped Downtown—Mall St. Matthews wouldn’t open for another two years. Nor had the elevated Interstates sliced through the urban fabric, killing off vast swaths of the city. No one could have known what an impact such large-scale suburban change was in store.

With little surprise, Guthrie Green was a huge hit. A report in the Courier-Journal noted that Guthrie Green “is getting more favorable local mention than primary-winning John Kennedy.” The temporary plaza was extended to run a full month.

Making it permanent

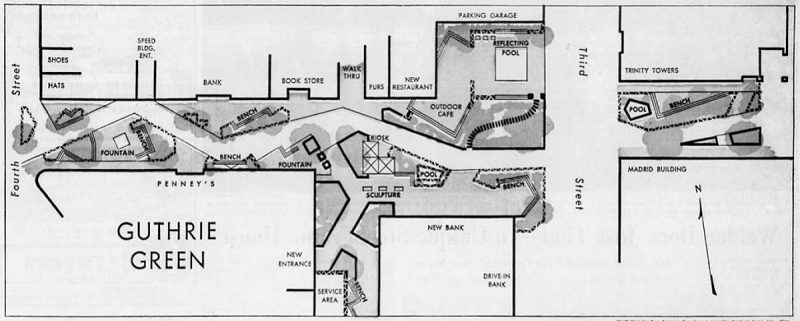

By 1962, LCA included a permanent Guthrie Green in its “Design for Downtown” report, but stepped back from a call for malling all of Fourth Street. In that same plan, the group also began a push for the city’s elevated system of pedestrian walkways and to build Founders Square at Fifth Street and Muhammad Ali Boulevard.

The plan won over Mayor William O. Cowger, who made building a permanent Guthrie Green his number one priority for the city. An ambitious plan stretching from Fourth Street past Third Street was drawn up by LCA.

Some business owners got cold feet at the large-scale plan. “Quite frankly, I wanted to go whole hog (in making a ‘green’ of the entire block-long strip),” Mayor Cowger told the Courier-Journal in June 1963, “but the property owners and the people who rent space along there didn’t want it.”

Ground was broken on a drastically downsized Guthrie Green on Wednesday, May 27, 1964. The green space stretched only 83 feet east from Fourth Street and only about 30 feet into the roadway, leaving room for one lane of traffic on Guthrie. It ended up more of an oversized neckdown than a full-scale pedestrian plaza.

The plaza was handcrafted by third-generation Italian mosaic and terrazzo artisan Giulio Cibischino of New York City. He finely honed the black–green stone finish on Guthrie Green’s planting beds and fountain. Off-white terrazzo marble paving, imported from Italy, was laid out in a paneled pattern. Cibischino also crafted the intricately detailed terrazzo map floor for the 1964 New York World’s Fair.

Guthrie Green was formally dedicated on Sunday, September 20, 1964. Mayor Cowger conducted the University of Louisville band before a crowd of 250 people.

The centerpiece of the pedestrian street was public art: a sinuous 800-pound bronze nude. Called “The Bride,” the artwork by British sculptor Reg Butler sprang from a bubbling rectangular fountain. The sculpture was a gift from the will of Dann C. Byck, whose Byck’s Department Store at the foot of Guthrie is now the Byck’s Lofts. Byck had been a major supporter of Guthrie Green’s construction.

“It speaks of youth to me and developing personality,” Mrs. Dann Byck said at the dedication. “That’s how I like to think of our community—young, vital, searching for something finer.”

Not everyone was pleased with the nude statue. One reader letter in the paper put it bluntly: “Is Guthrie Green to be an outdoor rendezvous for a lot of naked bodies masquerading as art?… Stimulating and provocative? You’re darn right—it will stimulate and provoke evil.”

Scaling up

In October 1970, LCA was back with another Tactical Urbanism move, this time with the aim of winning support to convert all of Fourth Street into a mall. This round of temporary intervention more resembled today’s CycLOUvia Open Streets program. For three days, motor vehicles were banned from Fourth between Broadway and Jefferson and pedestrians were invited to take over the street and enjoy car-free shopping. A tiny plaza, 50 feet by 25 feet, was set up with trees, benches, and fountains between Guthrie and Walnut.

Fifteen years after the H Plan, the idea of a pedestrian mall meant more than creating a pleasant streetscape. Suburban development was catching up with Louisville and Downtown was on the decline. The mall now represented a push to turn the area’s fortunes around. “The whole idea is to find some way of putting new life into the downtown area,” a Courier-Journal announcement explained.

The Mauling of Fourth Street

This time the idea stuck and Louisville agreed to build the River City Mall.

On Monday, July 12, 1971, the LCA unveiled plans for the River City Mall “with many of the glowing promises and forecasts that have accompanied other plans over the past decade,” the Courier-Journal‘s Joan Riehm wrote, at its annual meeting. The group had been pushing the scheme since it was founded in 1959.

There was also some concrete funding in place. “Jefferson County Judge Todd Hollenbach pledged $100,000 from a county revolving fund for the mall if the Fourth Street property owners accept the mall plan,” Riehm noted. The previous year, the “Kentucky General Assembly allowed the mall allowed the mall to be paid for by assessments against property owners on Fourth.” Mayor Frank Burke also pledged to widen Fourth Street’s alleyways, just as Hammerschlag’s plan called.

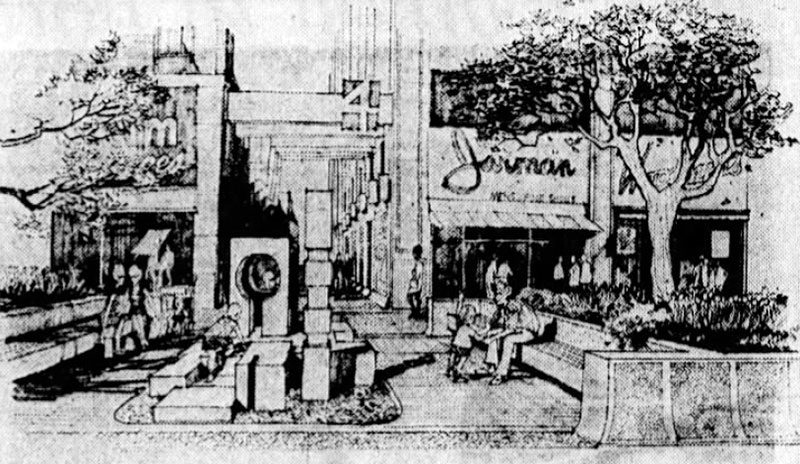

LCA paid Louisville’s Ryan Associates Architects and Johnson, Johnson & Roy Landscape Architects of Ann Arbor $5,000 to draw up the mall’s plans. “The design shows Fourth Street paved with brick and a path of textured concrete that snaked from side to side, giving a gentle optical curve to the half-mile-long street,” Riehm reported. The scene would be primarily composed in brick, concrete, and wood.

Hammerschlag, by this point a professor in Rhode Island, came back to Louisville to inspect the plans. He had helped build the Westminster Mall, a similar concept, in downtown Providence in 1965. He was cautious but optimistic of the Louisville plan. “The downtown mall is not going to reverse the trend to suburban shopping centers,” he warned. For Hammerschlag, the project was about beautification not bringing life back to a dying city, and six years into the Westminster example, he said the mall wasn’t performing due to the high costs of cleaning and maintenance (that mall failed and was reopened to traffic in 1986). But Louisville had the itch. It was going to have its own mall.

Fourth Street was officially closed to traffic on Friday, March 3, 1972. In June, Mayor Frank W. Burke signed $1.23 million contract with Al J. Schneider & Associates to build the River City Mall. The total project cost was estimated at $1.5 million.

By then, the stretch had already been closed by the city and much of the street was a construction site as utility companies rushed to coordinate underground facilities for the mall. To save money, the new mall design was eliminated from a half-block stretch of Guthrie Street, which was left with its older Guthrie Green design.

To build the mall, curb’s were torn up to create a flat surface. Clear paths wide enough to allow emergency vehicles access or proposed “people movers” to snake through.

Groves of trees created strange naturalistic settings in Fourth Street’s formal streetscape and chintzy plastic-roofed seating structures were built in the center of the street. Fountains and elaborate landscaping filled planting beds.

The ground place featured several raised plinths that served as impromptu stages for performances. A clock tower was planned and merchandising displays for retailers would be set up.

The River City Mall was officially dedicated on Friday, August 3, 1973. Louisville Mayor Burke, Hollenbach, and the general public packed the ceremonial walk through the mall. A performance of the “Stephen Foster Story” singers, pictured above was given on the mall’s raised theater stage.

Wilson Wyatt, Jr., son of the former Louisville mayor who first discussed the idea of a mall 30 years prior, was now in charge of the LCA, the group that tirelessly pushed the mall through for 15 years. Despite the project opening 8 months late, Wyatt was thrilled with the results.

He also credited the mall for a decision to build the city’s new $20 million convention center near its northern terminus at Fourth and Jefferson streets. “No doubt about it,” he told the Courier-Journal on a tour before the mall opened. “The pedestrian mall was the main factor in persuading Governor Wendell H. Ford to commit the state to the convention center,” the paper reported. In hindsight, it might have been a bigger boon to the city to have located that convention center elsewhere Downtown, given the amount of destruction of urban fabric that they have caused over the years. The River City Mall ended up being the anti-urban gift that kept on giving.

But besides the big state project to the north of the mall, all of the benefits Wyatt cited were still speculative by the time the mall opened. He cited “interest” and “considerations” for renovations to stores. No hard commitments or private investment that should have been going in tandem with the mall were it a real economic driver were cited. And that was a problem given the mall’s primary function was to be “catalytic.”

The problem was by the time the River City Mall was completed, many of the stores were already in trouble. Years of construction, delays, and street closures to build the mall didn’t help their economic outlook. It was still simpler for the suburbanite to drive to the mall, park, and walk around car-free paths with landscaping and fountains—and climate control.

There was no central authority or mechanism in place on Fourth Street that allowed it to manipulate its tenant mix or to dictate design rules like at suburban malls. The LCA’s dream of the River City Mall never recognized that it required an environment of total control to be effective. But that has long been the downfall of megaprojects and many an urban planner. There simply is no silver bullet.

Pedestrian malls can be effective tools in urban areas—they work quite well in dense European cities. But that density and core population is at the heart of what makes them work. Malls, as Hammerschlag warned, are not “catalytic” drivers but beautification projects. Rather than a focus on creating perimeter parking around the mall as the H Plan sought, had those garages really been dense apartment buildings then the River City Mall might have stood a chance at working.

The plight of the Louisville Clock

On March 30, 1980, a prominent headline ran across the Courier-Journal‘s Arts & Leisure section: “The plight of the clock-on-the-mall, or… welcome to hard times.” The paper’s art critic Sarah Lansdell detailed plans to move the sculptor Barney Bright’s mechanical Louisville Clock that could spring to life as a horse race of whimsical Louisville figures off of the Fourth Street Mall.

The clock’s delicate mechanics had already rendered it more of a stationary object on the mall, or as Lansdell described, an “archaeological specimen.” Despite its fussiness, the clock had developed its own following and remains a popular piece of Louisville iconography.

Bright was not pleased to see it go. “What bothers Bright most about the planned move is that the clock was designed for the place it occupies, a ‘defined area’,” Lansdell wrote. Bright described its site on Fourth Street allowed the artwork to perform on a stage setting where several hundred people could gather and watch the races.

The clock was not welcome at the planned Galleria, either by the developer Oxford Properties or by the fire marshal who dismissed it as a potential obstacle. A site on Guthrie was proposed, but then city so was putting it in storage. “That’s what some Frenchmen said about Louis XVI’s statue (now at Sixth and Jefferson) when they put it away for almost 150 years,” Lansdell cautioned.

Adding insult to the indignity, Mayor William Stansbury did not appoint the clock’s sculptor Barney Bright to a committee charged with finding it a new location.

The Louisville Clock was removed from the Galleria’s Fourth Street site by May. It was eventually reassembled in front of the J.C. Penney building at Fourth and Guthrie. But that move was short lived.

By 1985, city officials had hatched yet another plan for Fourth Street: a trolley path. The malling of Fourth Street had not gone according to boosters’ plans and the Transit Authority of River City (TARC) was leading an effort to rip out a 22-foot-wide path through the landscaped pedestrian street on which trolley buses could roll up and down Fourth. The Louisville Clock stood in the way of the $3.4 million project. By 1986, the clock was off Fourth Street again.

The Louisville Clock wasn’t the only piece of art to get the boot from the foot of Guthrie. After nearly 20 years, “The Bride” sculpture had had enough of Guthrie Green as well and traded up. When the Galleria opened in 1982, Byck’s opened a women’s store within the shopping mall, and Mary Helen Byck, Dann’s widow and company chairwoman, wanted to take the sculpture to the new outlet.

Today the sculpture resides in what’s left of Founders Square next to the Metro Development Center on Fifth Street. Louisville’s search for something finer had quickly passed up Guthrie Street.

Motordom returns

By the 1990s, Louisville was ready to give up on its decades-long experiment reinventing the street. The proposal to reopen Fourth to traffic first came from Alderman Paul Bather. After shutting down to traffic entirely and then timidly reopening to trolley buses, Mayor Jerry Abramson made reopening Fourth Street to cars a priority for his revitalization plan along the corridor.

City leaders cursed the earlier generation’s insistence on following a national pedestrian mall–building craze that ended up killing Fourth Street.

On Thursday, December 12, 1996, Fourth Street reopened to motorists. The street remained closed to traffic for four hours each day around lunchtime when trolley buses resumed using the street as a transitway. According to Sheldon Shafer’s 1996 report in the Courier-Journal, those Toonerville trolleys carried about 3,800 people each day.

That driver time-out wasn’t because the city was particularly fond of those trolley buses. It was a measure to avoid repaying the federal government the $2.2 million it gave the city to install the transitway in the ’80s.

To mark the $1 million reopening of the two-block stretch of Fourth Street, a ribbon was stretched across the street and a parade of vintage cars drove through it. But from Shafer’s report, it’s clear that many merchants still hanging on along Fourth Street still didn’t quite get it: after everything Fourth had been through, they were still trying to compete with the suburbs. “There still isn’t enough parking,” one merchant told Shafer, “a lot of people… don’t want to walk to stores.” “Parking is still a big problem,” another merchant said. What the River City Mall had failed to teach is that those people who require easy and plentiful parking just don’t shop Downtown.

While most waited tentatively to see what the latest change would do to street dynamics, Grady Clay, who had put such high hopes into the pedestrian mall concept, now maintained a thoroughly pessimistic outlook on Fourth Street. Clay told Shafer that Fourth would never return to its former prominence as a hub of culture and retail. He faulted the River City Mall with not providing enough parking from the outset, as the H Plan called for, dooming it to failure. It’s likely, though, the mall would have failed regardless of how much parking was built. Building more would have just made the hangover worse.

Reopening the street as an actual street did pay off in the end. Within a year, Fourth Street’s 80 percent vacancy rate dropped to 50 percent and property values increased, according to analysis by Dr. Kharbawy of Fresno State University. Since then, both the image and the economic outlook of the street have continued to improve. Development has picked up and new local retail has opened, but vacancies remain, some landlords show little interest in renting their property, and national retailers have been elusive despite the best efforts of city leaders.

How low can you go

Guthrie Green also took on its final form that lasted another two decades before it was removed for good. Drab synthetic pavers were installed from wall to blank wall and Fourth Street till the alley. A handful of concrete planter–benches dotted the lifeless expanse. While this scale of pedestrian mall might very well have worked for Louisville, but the cards were stacked against its success and the city wasn’t particularly interested in pedestrian malls any longer after everything it had just been through.

The situation on the ground—no retail space and an ugly design—ensured that the plaza was little more than a windswept expanse of pavers. There was absolutely no reason to use it, and the only people regularly seen there were those out for a smoke break. Even the homeless opted for more comfortable hangouts.

Then the city flat out gave up. With nothing much happening along Guthrie Green, eventually the city decided the pedestrian plaza itself there was the problem. The already drab space stopped being maintained and trees were removed, causing it to be dually wind-swept and sun-baked. Perhaps in a moment of foreshadowing, utility workers ripped out a line of pavers and put back a black line of asphalt through the space. Guthrie Green’s sea of paving had unofficially been parted by the asphalt that would soon make it back into a street.

The Speed Building had for a long time boarded up some storefronts and converted others to offices that didn’t promote street life. Across the street, our block of Fourth and Guthrie had been remade one more time with the recladding of the old J.C. Penney and W.T. Grant buildings.

Windows were punched into three-story structure to make it usable as an office building. The ground floor’s large plate glass storefronts and its marquee-like awnings were removed. The structure’s beige brick and bas reliefs were covered over in more drab pink and off-white faux-stucco EIFS and the facades of both buildings were united into a single visual block. Combined with the parking garage, whose retail space was vacant, vertical panels removed, and concrete decaying, Fourth and Guthrie had hit architectural rock bottom.

A festival in the street

As we mentioned in the beginning of this epic tale of Fourth and Guthrie, the ribbon was cut on the new Guthrie Street in June 2015. That’s exactly 100 years since the street appeared on the scene in the first place.

At the reopening of Guthrie Street, city officials including Mayor Greg Fischer and the Louisville Downtown Partnership’s Executive Director Rebecca Matheny touted the new throughway as a sign of the economic vitality of Fourth Street and as a boon to business in the area.

Matheny said the curbs were specially designed with a profile that could accommodate large events and food trucks, noting that the street would become a fixture of events in the area. As a demonstration—or perhaps to show that a car street could still be fun—five food trucks lined the parallel parking spots along the street during the announcement.

Strangely, the Courier-Journal‘s Sheldon Shafer reported the following in announcing the ribbon cutting, emphasis added:

But city officials never got around to reopening Guthrie, a closure that for decades curtailed pedestrian circulation near the Guthrie-Fourth intersection. It also impeded access to the large Speed Building, which has numerous office tenants and is located on the northeast corner of the intersection, city officials said.

“The reopening of Guthrie Street removes the last vestige of the 1970s-era River City Mall initiative,” Matheny said at the event. “A street that does only one thing is not a healthy street.” She compared the opening of the pedestrian street to automobile traffic to “a complete street approach…that will better serve our Downtown.”

While the old Guthrie Green was no prize of a public space, it seems odd to characterize it so negatively as impeding economic activity and posing a barrier to pedestrians. Certainly the space badly needed a redesign, but the new Guthrie Street, dominated by two lanes of car traffic and a parking lane, with pedestrians pushed back onto narrow sidewalks on either side, doesn’t seem on the surface like such an improvement. Or even much of a complete street.

We’ve swapped one primary user for another—pedestrians to motorists—while ignoring the underlying reason Guthrie Green wasn’t working in the first place: problems with privately owned buildings.

The real issue at Fourth and Guthrie remains retail space, and that’s not one a government can readily solve. If the owner of the Speed Building doesn’t want to change the sidewalk level of the structure, the same problems of Guthrie Green will remain only this time pedestrians have to dodge car traffic.

That retail space is not magically now viable because a motorist can pull right up curb side rather than walk 50 feet through a plaza. If anything, the potential of those storefronts has now been diminished because the sidewalks are too narrow, for instance, to permit sidewalk dining for a local restaurant.

Just as the original Guthrie Green solution to beautifying Downtown didn’t scale up to all of Fourth Street, the opposite might also be true: the reopening of a street to motorists may not scale down to work effectively on Guthrie. The Green’s small-scale demeanor has been lost and what we get in return is so far uncertain.

The city paid $500,000 to reopen Guthrie, which included utility work from LG&E. The streetscape design roughly matches an entirely new, award-winning streetscape the city has been unrolling through the Fourth Street corridor from Muhammad Ali Boulevard to Broadway.

What’s next?

The stage is being set, yet again, for another rebuilding of Fourth and Guthrie. Just this week, a Cincinnati developer has proposed building 237 apartments within a seven-story structure on the site of the old J.C. Penney and W.T. Grant buildings. Those plans can be viewed over here.

A 20-step program

While we await the next chapter at Fourth and Guthrie, let’s recap the numerous changes that brought us to the present day.

- Nearly 200 years ago, the site is first built with residences.

- The site is rebuilt as the Industrial Exposition of 1872.

- The feds build a magnificent U.S. Customs House & Post Office.

- Guthrie first appears as a small alley.

- Guthrie Street is made a real street in 1915 by the Speed Realty Company.

- Lincoln Park emerges on the Customs House backlot.

- Lincoln Park is redesigned.

- The Customs House is torn down.

- Lincoln Park is expanded.

- The site is built up with 1950s department stores.

- The concept for a pedestrian mall is born at Yale in 1955.

- Guthrie Street hosts the city’s first Tactical Urbanism event in 1960.

- Guthrie Green is built in 1964.

- The River City Mall is built in 1973.

- Guthrie Green loses its centerpiece artwork to the Galleria in 1982.

- The mall is converted to a transitway in 1986.

- The department stores are reclad as office buildings.

- Fourth Street reopens to cars in 1996.

- Fourth Street is remade with a new streetscape.

- Guthrie Street reopens to cars in 2015.

- Fourth & Guthrie is proposed to be rebuilt as apartments in 2016.

That’s quite a bit of change for one intersection.

[Photo credits: Unless noted, historic photos courtesy University of Louisville Photo Archives. General Fourth Street: Reference, Reference, Reference, Reference, Reference. Guthrie Street: Reference, Reference, Reference, Reference. Post Office: Reference. Lincoln Park: Reference, Reference, Reference, Reference, Reference. Speed Building: Reference, Reference, Reference. JC Penney: Reference, Reference, Reference, Reference. WT Grants: Reference, Reference. Parking garage: Reference. ]

Branden, you are on fire. Amazing and informative article.

Wow. Thanks, Branden, for this splendid scholarship. I wish the City and developers worked as hard as you do, and really thought about what makes a city as deeply.

Great article. I wish the city had someone like you working for them.