[Editor’s Note: Louisville has made some pretty amazing achievements in its first 238 years—but it’s made a few blunders along the way, too. This week, we’re launching a new contributed mini-series documenting eight of the best and eight of the worst decisions, ideas, or projects that have profoundly affected the city. This list is by no means complete—and you may have strong opinions of your own about what should be on the best or worst lists. Share your thoughts in the comments section below. Or check out the complete Best/Worst list here.]

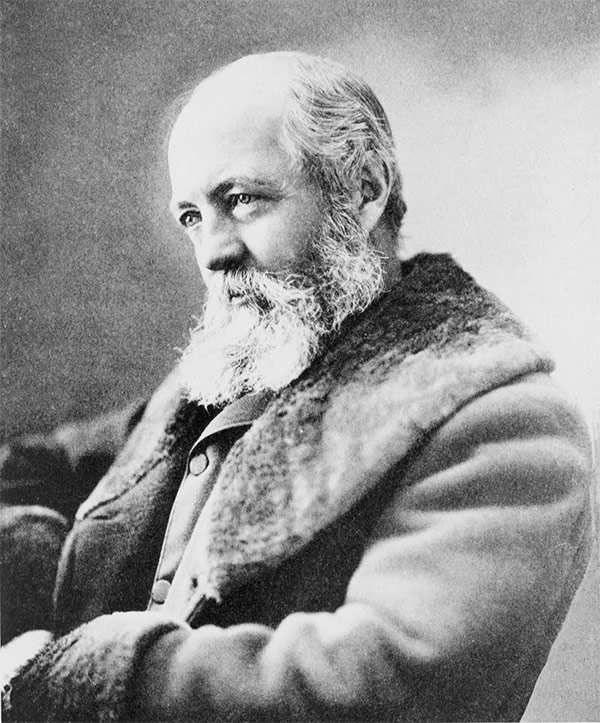

May 20, 1891, is a landmark date in Louisville planning history. That was the day when Frederick Law Olmsted—the Father of Landscape Architecture himself—arrived in Louisville by train from Chicago where he was preparing the World’s Columbian Exposition that would dazzle the world when it opened to the public in 1893.

Olmsted was in town to speak to a select group of civic leaders at the Pendennis Club. Shortly thereafter, Mayor Charles Jacob commissioned Olmsted to develop a parks system for the city. Olmsted, after all, was the famed designer of New York City’s spectacular Central Park in 1857 and Prospect Park in 1867.

Prior to hiring Olmsted, the business community had set out a grand vision. City leaders wanted Louisville to retain its position as one of America’s top tier cities, and to do that, they sought to expand its manufacturing base. To achieve this, the city needed more blue collar workers for these factories. And parks played a key role in attracting that labor force to the city. Thus, they saw parks as an economic development strategy.

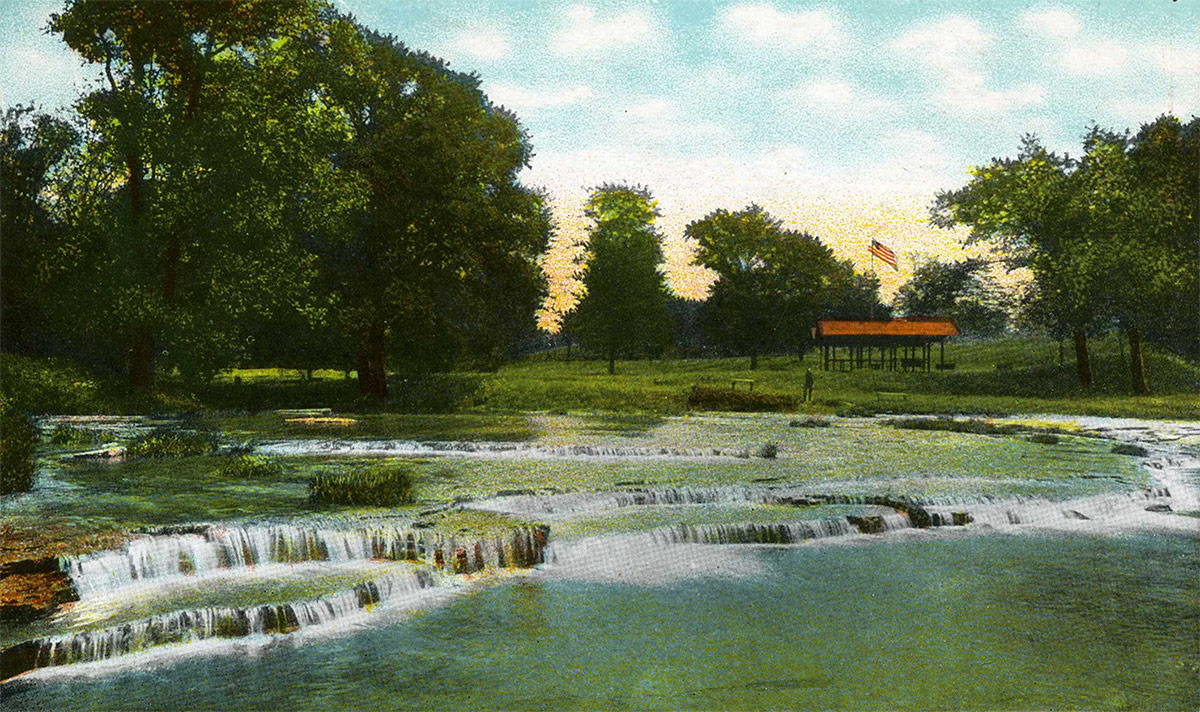

To Louisville’s early industrialists—and very much to Olmsted—parks were a way of improving the health of cities by providing pastoral landscapes in which the working class to escape the tedium and pollution of city life. These so-called “pleasure grounds” were spaces for workers and their families to enjoy and relax, since they could not afford large landscaped yards or travel abroad.

While Frederick Law Olmsted is touted as the mastermind of Louisville’s parks system, he actually only worked on the initial conceptual layout. By the mid-1890s, Olmsted was in his early 70s and suffered from deteriorating health. His sons, John Charles Olmsted and Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., succeed their father in implementing the Louisville park system. The duo formed their new firm, Olmsted Brothers, in 1898.

One other person also needs to be recognized for making certain the parks were built: Andrew Cowan. Cowan was not a native Louisvillian but relocated here after a distinguished military service in the Civil War.

Cowan is recognized as one of the heroes at Gettysburg, where he kept his cannon battery focused on repelling Pickett’s Charge on July 3rd, 1863.

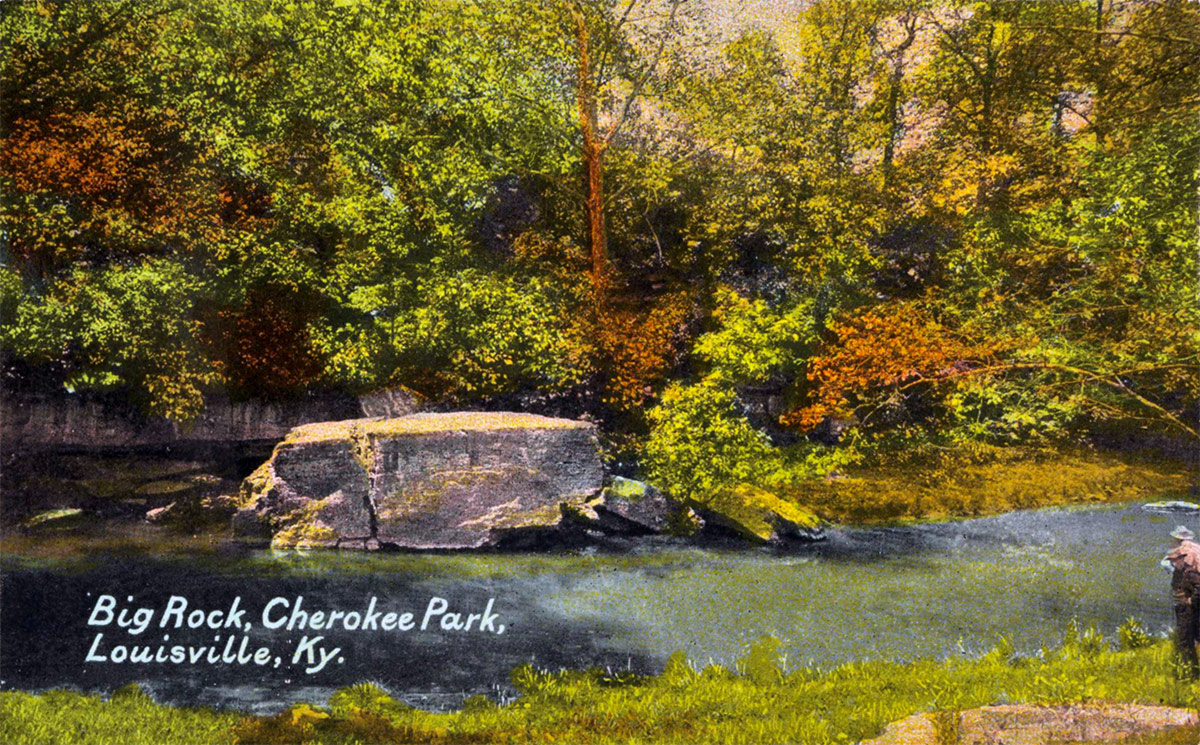

It was Cowan who guided Olmsted around to the various proposed park locations during his 1891 visit. He became passionately dedicated to getting the parks implemented. Cowan eventually built a magnificent mansion adjacent to Cherokee Park, near Big Rock.

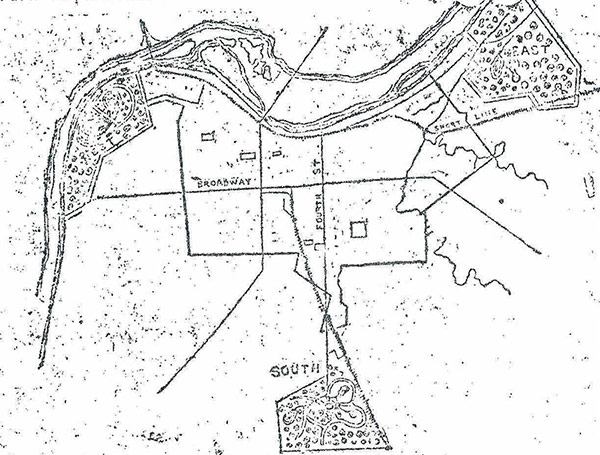

Described as an Emerald Necklace around the city, the three major parks—Shawnee, Iroquois, and Cherokee—are all connected via landscaped parkways, although there are a few gaps. To this day, Eastern Parkway terminating at Cherokee Park, Southern Parkway leading to Iroquois Park and Algonquin Parkway and Southwestern Parkway pointing to Shawnee Park are among Louisville’s most pleasant thoroughfares lined with majestic oak trees and stately homes.

Once the Olmsted brothers had built these three masterpieces, there was plenty of demand for more projects from those around Louisville enamored with the beautiful landscapes. Many smaller city parks—Central Park, Shelby Park, and Chickasaw Park, among others—bear the signature Olmsted design sensibilities. Many stately mansions throughout the city, lining the parks and perched atop river bluffs, are also surrounded by Olmsted landscapes.

Louisville’s Olmsted Parks System is today overseen by the Olmsted Parks Conservancy and Metro Parks. The parks system is undeniably a magnificent amenity for the residents of Louisville and a major asset to their quality of life. The civic ambition that led to their creation is one that should inspire us to this day.

Great article! And this qualifies as a huge “BEST”. Thank you for the coverage as its always fun to learn about the city no matter how long you’ve lived here.