It’s once again Preservation Month across the country—and it’s a big one. This year’s celebration of the built environment marks the 50th anniversary of the National Historic Preservation Act and the founding of the Kentucky Heritage Council, the state agency that keeps track of historic and archaeological sites and oversees listing structures on the National Register of Historic Places.

While in Louisville warmer spring weather typically means the demolition schedule kicks into full swing with new wrecking permits filed in higher numbers (over two dozen have been issued since April), our local preservation outlook is in many ways very good. There’s change in the air that has the potential to redefine what preservation means and how it’s practiced—and that’s exciting. Let’s check in with where we stand across the city.

Preservation in Louisville in 2016 is certainly at a turning point. One year ago, the city was embroiled in a heated debate over the razing of several historic buildings on the site of the under-construction Omni Louisville Hotel, most prominently the former Water Company Headquarters. While most of that structure is at the landfill, a portion of its facade is currently disassembled in storage awaiting a reuse proposal (along with several other facades of demolished buildings from around the city).

The public process relating to preservation at the Omni block, like most of the city’s big preservation battles, is best described as reactionary. It always seems like a game of catch-up and that can come off in the public sphere as being obstructionist. But that doesn’t mean preservation is not a critical and worthwhile endeavor. It’s just a symptom of a system that doesn’t really understand how preservation fits into the bigger picture—and we’re figuring out now how to fix that.

Preservation works best when it gets out in front of the game, can work with all the players early on in the conception of a project, and find solutions that don’t feel like fights. Preservation—and preservationists—certainly don’t want to stymie development outright even though that’s sometimes how the media portrays these groups. The bigger picture is a better Louisville, and creative thinking on economic development, place, and how our existing resources fit in will make us more competitive nationally.

Preservation Task Force

So there’s good reason to believe that we’re making progress. On May 2, Mayor Greg Fischer announced the creation of an Historic Preservation Advisory Task Force that will recommend policies around planning and preservation.

“With the creation of this task force,” the mayor said in a press release, “we as a city will now have a better, proactive way to catalog our historic resources and identify best practices for adaptive reuse.”

The task force is charged with four primary goals:

- To define a system to inventory and prioritize the city’s heritage urban fabric.

- To identify key structures from endangered lists and develop a treatment plan to achieve the best outcomes.

- To recommend financial or policy incentives that support redevelopment and historic preservation.

- To suggest best practices in redevelopment and historic preservation which can inform Louisville’s coming Comprehensive Plan update.

The task force, according to the city’s announcement, will be comprised of the mayor or his representative, a Metro Council member appointed by the council president, and 14 to 21 citizen members appointed by the mayor. The committee is filled with landmarks commissioners, developers, and representatives from the Kentucky Heritage Council, the Louisville Downtown Partnership, Samuel Plato Academy, and Institute of Healthy Air, Water, and Soil. Metro Louisville’s Historic Preservation Officer and its economic development department Louisville Forward will provide staff support.

“The task force is an outgrowth of what went on last summer,” Keith Runyon, co-chair of the group and former Courier-Journal editor, told Broken Sidewalk. He noted that an ongoing partnership between Louisville and the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Preservation Green Lab (PGL) helped the task force take shape over the past year. We interviewed PGL’s Jim Lindberg in Denver’s beautifully restored downtown train station last year to learn more about the group and its efforts in Louisville.

“Jim Lindberg was involved over the past year in discussions with the mayor and others about how to form a more effective and less combative paradigm for future issues,” Runyon said. “And there will be future issues. It’s built into the system that there will be. I think there are ways we can do so less confrontationally than last summer turned out to be.”

And a task force looking at the issues with a fresh face isn’t a bad way to start.

Preservation Louisville

Meanwhile, the city’s top preservation nonprofit, Preservation Louisville, is undergoing an evolution of sorts. That group’s founding executive director, Marianne Zickuhr, quietly stepped down at the beginning of 2016, taking a full-time position at the growing ArtxFM radio station.

Meanwhile, the city’s top preservation nonprofit, Preservation Louisville, is undergoing an evolution of sorts. That group’s founding executive director, Marianne Zickuhr, quietly stepped down at the beginning of 2016, taking a full-time position at the growing ArtxFM radio station.

To fill the void, Runyon, an active voice in last year’s Omni v. Louisville Water Company debate, has filled the role of Preservation Louisville’s interim spokesperson and coordinator. A search for a new director is in the works, but no timeline exists for filling that position. “I never really wanted to be executive director of anything, especially after I retired,” Runyon said.

Runyon said he is coordinating Preservation Louisville’s annual Ten Preservation Success Stories list, featuring cameos of good work taking shape around the city, and the corresponding Ten Most Endangered Building list, highlighting particularly vulnerable properties. Both are traditionally released in May, and Runyon said this year should be no different.

Preservation Louisville’s board or directors is also evolving. In late 2015, attorney Thomas Woodcock assumed the role of board chairman and president from urban planner Charles Cash, who will a keep a seat with the body.

“We’re optimistic,” Woodcock told Broken Sidewalk. “We’re excited to see a diverse board, the mayor’s task force. This will help refocus some of Metro Louisville’s attention on preservation—on what’s authentic about Louisville.”

Cash agreed. “We’re in a transition period,” he said of Preservation Louisville, “and I think everyone will be pleased with the outcome.” But for now, details are being guarded.

Big plans at Save Our Shotguns

Neither Cash nor Woodcock would give specifics on what’s planned at Preservation Louisville, but we suspect they could be major. “We have a number of things in store,” Woodcock said. “We’re going to have a big announcement coming up about our Save Our Shotguns (SOS) campaign.”

That reminded us of a tidbit that came to light last month when developer Edwards Companies announced it would, after all, move forward with two major residential projects along East Broadway. We’ve known for a long time that a series of five shotgun houses that sit on the western edge of the Phoenix Hill Apartments site would be saved, but in April Edwards Companies revealed that those houses would be donated to a local preservation nonprofit. We’d bet that’s Preservation Louisville. Woodcock would neither confirm nor deny that the two are related.

Historic Precedent

With so much change coming to Louisville’s preservation community, it’s important not to ignore a historic precedent about a very similar story that went a very different direction. Runyon explained the rise and fall of an older nonprofit, Preservation Alliance, and how we’ve learned from the mistakes of decades past.

(Image references: One, two, three, four, five. Reference for Luckett below: one.)

Runyon recalled the heyday and downfall of Louisville’s former heritage group, Preservation Alliance, which had no small task of defending the built environment of the city in the difficult period of the 1970s and ’80s. The battles that group faced—and the landmarks they were fighting over—make our modern-day efforts pale in comparison, even though they’re no less important. Preservation Alliance helped to defend the giants of Louisville’s architectural heritage. Sometimes they won and sometimes they lost.

“Preservation Alliance was formed in that yeasty era in the early ’70s after urban renewal had destroyed so much of the urban environment in a way the public had been completely uninvolved in,” Runyon explained. “It was a very effective and high-profile organization in the late ’70s.” He added that membership within the organization carried with it a certain cachet and its ranks included many big names. “In my day it was an organization you wanted to belong to, he said. “They made it interesting.”

It was during the early days of Preservation Alliance in the 1970s when Louisville’s Landmarks Commission, one of the first such groups in the country, was established to review preservation cases in the city.

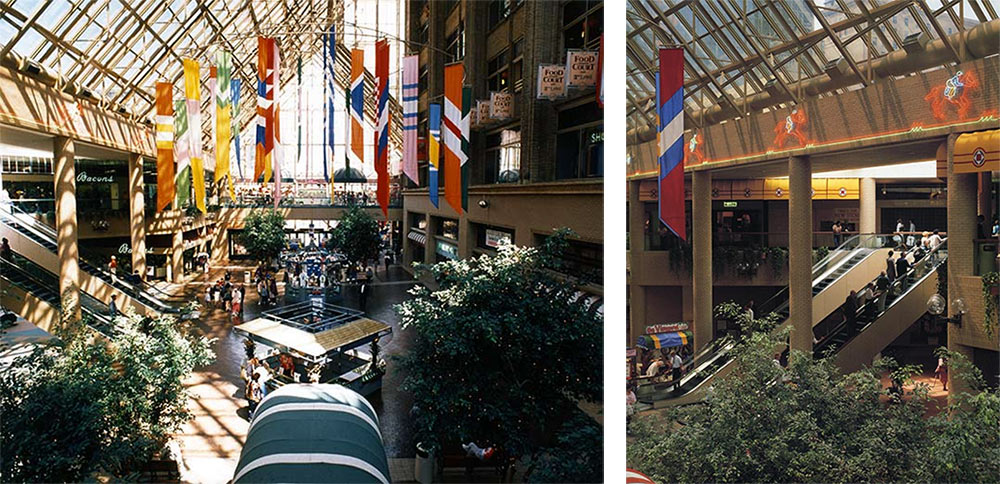

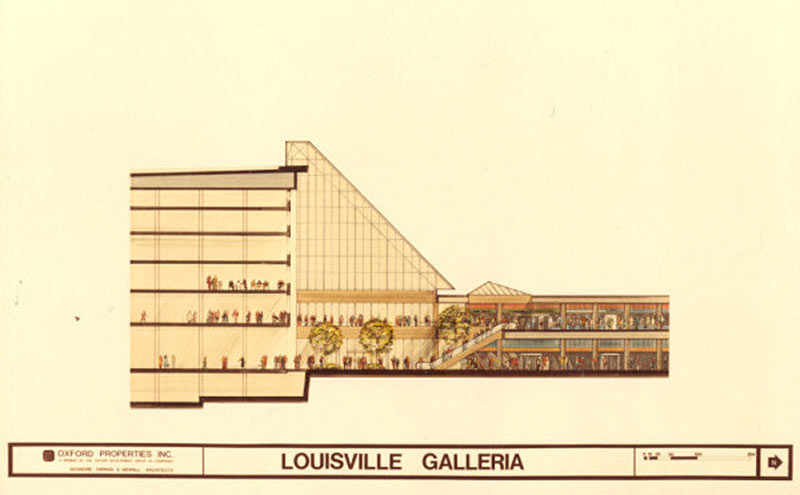

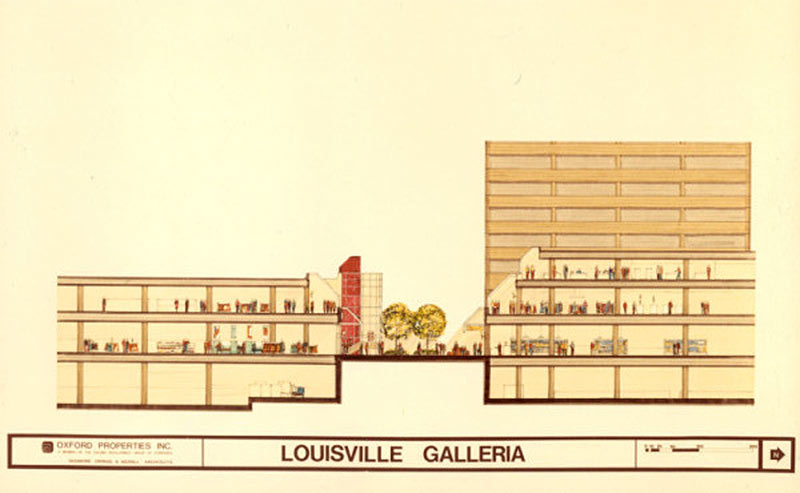

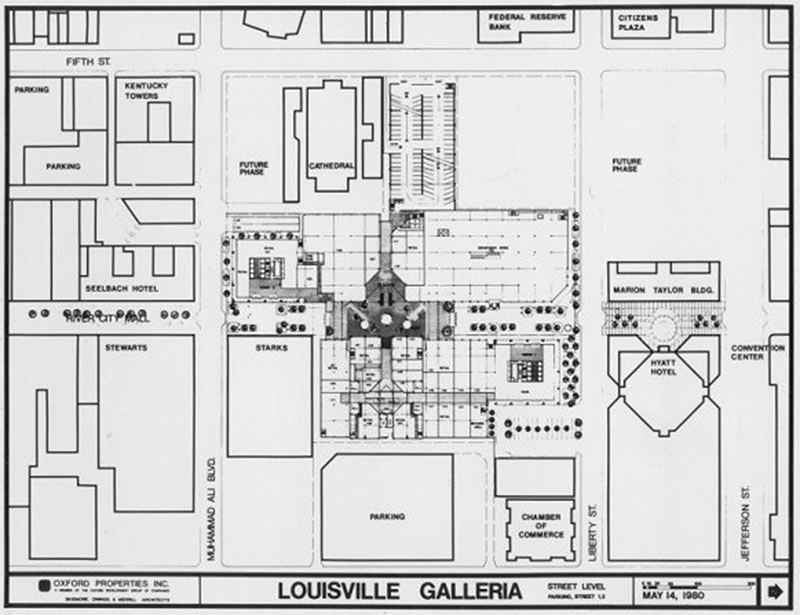

And while Preservation Alliance was doing good work all around the community, eventually a big enough development project—scaled perhaps similarly to the Omni—eventually presented a major fight for the organization. We’re talking here about plans to build the Louisville Galleria from the ashes of the failed River City Mall, which had opened Fourth Street as a pedestrian mall. We all know what happened to the Galleria.

By the ’80s, “Preservation Alliance had gotten a black eye,” Runyon recalled. “They tried to incorporate historic buildings into the Galleria.” The group pushed for including full buildings and then building facades of many gorgeous, large structures around the failed Fourth Street shopping mall. “I think if they had been able to do that, 4th Street Live! would be a much more exciting place,” he said.

The Will Sales Building, formerly the Courier-Journal Building, which anchored the corner of Fourth and Liberty streets was ultimately demolished in 1979. Following the fight, “a lot of business community thought an organization like this was not useful,” Runyon said. “What happened to it was, I think, what was about to happen to Preservation Louisville.”

“Because of the incredible battle that occurred over the building of the Galleria and the demolition of buildings on Fourth and Liberty,” Runyon said. “And before that the construction of the Convention Center.”

“Preservation Louisville is the successor to Preservation Alliance,” Runyon continued. “It came along in the late ’90s.” He thinks the group is resilient enough to withstand the recent storm surrounding last year’s Omni Louisville Hotel decisions. And certainly that group has had its fair share of high profile victories including helping to save the high-profile Whiskey Row Block, among others.

Plus, the city and Preservation Louisville have a few modern tricks up their sleeves, namely in a partnership with the National Trust’s Preservation Green Lab (PGL), which explores new data-driven discussions in which to frame preservation, including sustainability and economic development.

The Right Direction

We’re excited about change coming to preservation in Louisville—and so are many who are at the front lines of the movement. As a word, preservation is about to take on a whole new meaning. One that can fundamentally change how we treat our built environment. And we’re hoping we can get it right.

“I think the idea of having a community discussion about preservation and its role in urban development is a very good thing—probably long overdue,” Cash told Broken Sidewalk. “I’m hopeful there will be more proactive results that come out of it.”

And that’s hopefully exactly what will happen between the efforts of the Preservation Green Lab, the formation of the mayor’s task force, changes coming to Preservation Louisville, and speculation over what might happen along East Broadway.

“I’m hopeful one of the things this task force takes a look at is what matters to people,” Cash said, noting how large crowds are attracted to Downtown and Old Louisville events not just for the activity, but also for the heritage surroundings. “That’s a discussion that we have never really had.”

“I think we’ve always had more of an academic approach to what is eligible for the National Register,” Cash added, describing Louisville’s difficult relationship with the words “historic” and “old.” “That’s a different discussion for what matters to the community and what’s important for the future.” Cash noted that a lot of preservation work in the future will involve buildings that are old, but not traditionally considered historic. It’s those kinds of buildings, like the series of East Main Street structures being converted into the Butcher Block, that are vital for rebuilding Louisville and creating economic development opportunities.

Jane Says

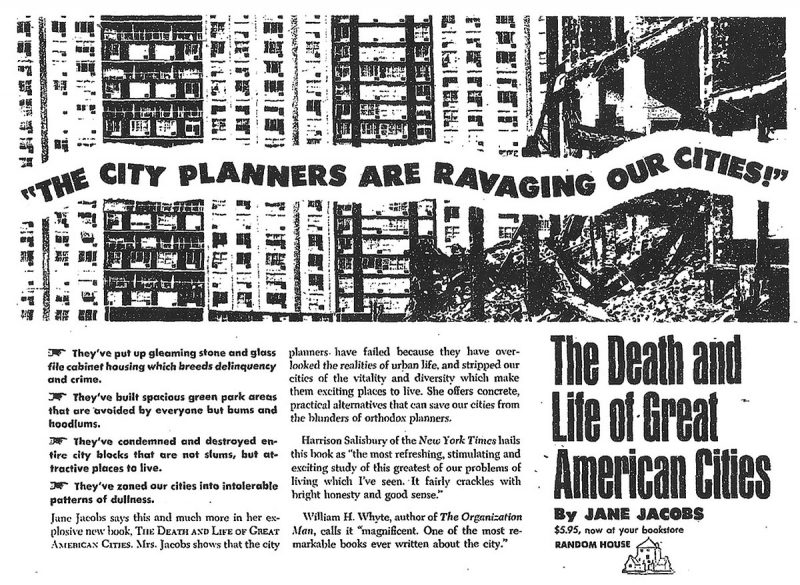

And we’ve known this for a long time—since all the way back in the 1950s and ’60s. Jane Jacobs is often quoted as a pioneer in recognizing the value of old buildings beyond the typical notions of preservation.

“Cities need old buildings so badly it is probably impossible for vigorous streets and districts to grow without them,” Jacobs wrote in her pivotal book, Death & Life of Great American Cities, in a chapter titled “The Need for Old Buildings.” She continues:

By old buildings I mean not museum-piece old buildings, not old buildings in an excellent and expensive state of rehabilitation–although these make fine ingredients–but also a good lot of plain, ordinary, low-value old buildings, including some rundown old buildings.

If a city area has only new buildings, the enterprises that can exist there are automatically limited to those that can support the high costs of new construction.

…

Perhaps more significant, hundreds of ordinary enterprises, necessary to the safety and public life of streets and neighborhoods, and appreciated for their convenience and personal quality, can make out successfully in old buildings, but are inexorably slain by the high overhead of new construction.

As for really new ideas of any kind—no matter how ultimately profitable or otherwise successful some of them might prove to be—there is no leeway for such chancy trial, error and experimentation in the high-overhead economy of new construction.

“Old ideas can sometimes use new buildings. New ideas must use old buildings,” Jacobs famously concluded. And we’re seeing that these words are as true today as when Death & Life was published 55 years ago in 1961.

[Top image of West Main Street courtesy jpellgen / Flickr.]

So all that work we now irrelevant people did is in the dust bin along with many

More relevant buildings than we care to discuss ?! Roll through Old Louisville and see what the last five years of paying scant attention to the crisis unfolding in established districts is doing. I have never in my nearly forty years of oversight in this field seen the level of disrepair and nearly catastrophic loss that will soon occur if preservation standards are allowed to further erode into nothing. It breaks my heart. Jane is correct. It’s the little buildings that count – and all the task forcing in the world ( note how nobody who actually did all this heavy lifting was included in its make up) will not put rotting cornices back, or repair failing walls or keep the leaking roof from caving in. That’s where we started and this is where it ends.

As a fellow colleague said to me recently, we’ve become irrelevant . And so we have.

Just another addition to a town with enough obstructionists to development within it Already.

http://www.wdrb.com/story/32064831/ruling-city-of-louisville-can-legally-move-confederate-monument-at-u-of-l

Where are all the preservationists at now? This just proves that you are all hypocrits. You do not want to preserve history, you just want to impede progress. If you actually cared about preservation, you would be attempting to preserve this monument, no matter how you felt about it or what you believe it represents.

If the city is offering to pay for the respectful moving and preservation of an entire building that is hurtful to a huge group of people I would hope preservationists would be on board. Sounds like this situation hasn’t ever come up yet so I don’t know what you are on about, as usual, Mr. Hawkins.

You guys are just hypocrits, that is what I am on about.