The first weekend of the newest round of the vacant-lot-reclaiming ReSurfaced project has come and gone. (Tell us what you thought of it in the comments below!) But while you’re sipping craft beer, admiring the colorfully lit shipping container design, or musing on how to revitalize Phoenix Hill, it’s worth putting some thought on how ReSurfaced’s Liberty Build site and surroundings came to be the barren fields dividing Nulu and Phoenix Hill.*

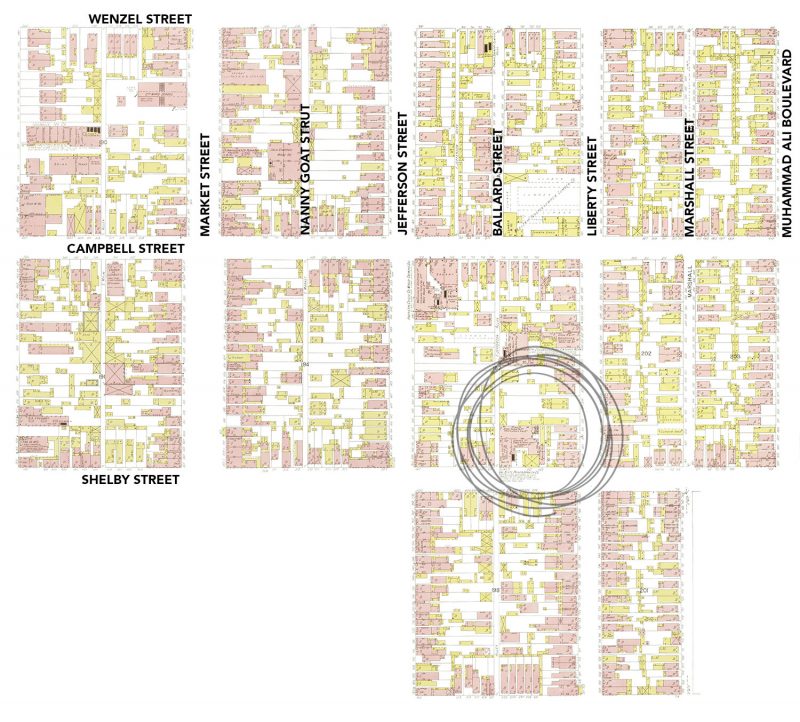

While there’s a lot of historic architecture remaining in the area, this stretch of Phoenix Hill at Liberty Street and Shelby Street would have looked very different a century ago. This would have been a robust residential neighborhood of mostly brick houses, corner stores, some industry, and quite a few horse stables. And it would have been very dense.

Back in 1905, the ReSurfaced corner was occupied by two three-story corner buildings with residences above a saloon, eight shotgun houses, a bowling alley, three two-story homes, and the Val. Blatz Paint & Varnish Company. That company was housed in a complex of structures, the largest being a three-story brick building on Shelby Street.

Over the decades, the block gradually shifted from from residential to industrial. The houses on Liberty Street—then called Green Street before it was renamed in the patriotic fervor of World War II—were torn down for parking lots and warehouses as the varnish company grew and transportation trends changed.

While much of the neighborhood remained intact through the 1970s, a large chunk had already been removed by 1939 when the city razed half a dozen city blocks for the Clarksdale Homes. Clarksdale was the city’s first housing project, built in a barracks style that came to dominate such schemes. The original buildings had flat roofs that were later modified with pitched roofs, adding a domestic feel to the otherwise institutional complex.

Clarksdale’s 58 structures were originally built as segregated white-only housing, according to Wikipedia, but by the 1960s white flight had taken its toll and the housing became majority black.

With that white flight came disinvestment in the neighborhood. Often disinvestment has the side effect of helping to preserve the built fabric of a place. It’s the same reason we still have the beautiful structures along West Main Street—they were so forgotten that no one thought it worth the money to tear them down. Many historic buildings remained in place, including that old varnish factory.

Urban Renewal cleared what private investment didn’t, making way for the Clarksdale Homes, Dosker Manor, and an interchange for Interstate 65. All told, nearly a dozen city blocks were leveled for those projects.

Largely written off, this part of town began to cater to the population that remained and became home to organizations that worked to provide social services, including many homeless shelters and spaces for addiction recovery. While the largest, Wayside Christian Mission, relocated off East Market, many of these institutions still remain today.

And their presence has complicated ReSurfaced slightly—or perhaps highlighted a topic for discussion that such tactical urbanism projects are meant to do.

Recently, the Jeff Street Baptist Community’s Reverend Cindy Weber publicly decried alcohol at the pop-up venue and the congregation voted unanimously to oppose its sale. The Jeff Street Baptist Community is located across the street from ReSurfaced at 800 East Liberty Street and, among other things, serves recovering alcoholics. (Find more at Insider Lou, Biz First, WDRB, WLKY, or the C-J.)

City Collaborative, the driving force behind ReSurfaced, has since met with the community leaders and is working to find a compromise. It noted that several members of the congregation were among the volunteers that helped built the pop-up. As activity spills off East Market into the surrounding blocks, the old and new histories of the area will need to find balance.

Back to the 1970s. Eventually, the Phoenix Hill neighborhood began to erode, especially along this edge condition created by the disparate urbanisms of the housing project and the neighborhood. The barracks layout of the Clarksdale Homes failed in its anti-urban form, serving to create a barrier that had the effect of casting stigma on the houses and the entire neighborhood.

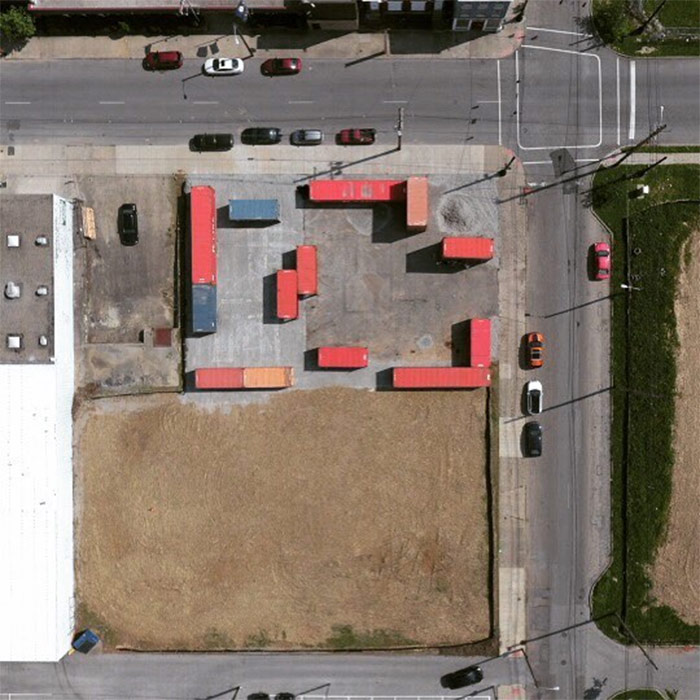

The old industrial buildings on the ReSurfaced site comprising the varnish company remained for some time, clearly visible in the above 1993 aerial view, but by this time, the there were no residences on the block.

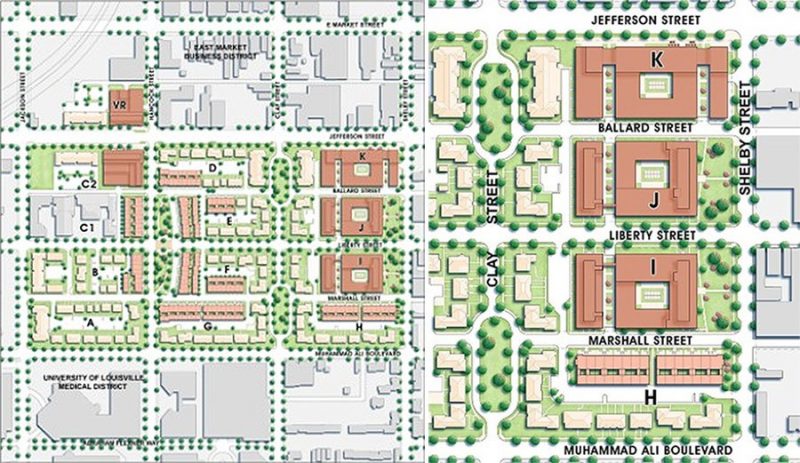

By 2002, not much had changed. The Clarksdale housing projects were still standing, but nearing their end—they would be demolished in 2004–2005 to make way for the HOPE VI development of Liberty Green.

These were the days well before Nulu—Gill Holland’s Green Building didn’t open until 2008 and much of what we consider the heart of Nulu followed after that. And we’re just now seeing development begin to edge off of the East Market strip that’s been growing for the past decade.

But along with the demolition of the projects came demolition of the remaining structures along Shelby Street. Not that there was much remaining. It was at this point that the last of the varnish factory was torn down. It’s loading dock, sunk into the ground along Liberty, can still be seen today. Later, a small storefront to the north and a two-story commercial building a block south would also go.

Liberty Green’s mixed-use, mixed-income model based on the tenets of New Urbanism brought significant change to what was once barracks housing. But some areas slated for private development like the eastern edge along Shelby Street have been slow to materialize.

The Louisville Metro Housing Authority built dozens of traditionally designed apartment buildings and houses on the western and central portions of the site. A number of market-rate townhouses and apartments were also built along the Hancock Street corridor. But the eastern section along Shelby Street today remains unbuilt.

Compounding the problem, those vacant lots serve as a sort of slap in the face to the neighborhood. Their central alleys and parking lots that new housing would eventually be built around were constructed early on, but along the perimeter no sidewalks have existed for over a decade.

Since around 2005, both sides of Shelby between Jefferson and Liberty (and the east side till Muhammad Ali Boulevard) have been flat vacant land or parking lots. And now ReSurfaced has stepped in to add activity once again to the long-quiet site.

Today, however, ReSurfaced is exploring ways to bridge the gap created by this vacant land and repair the tattered urban fabric separating Nulu and Phoenix Hill. ReSurfaced opens up again this weekend and again later this fall as it continues on its 18-month schedule, and it’s inviting the community to confront these issues that have shaped the area over the past century head on.

Share your thoughts on ReSurfaced, the surrounding urban fabric today, and how we might improve the city here in the comments below. And stop by ReSurfaced this weekend to inspect the situation for yourself. And if you’ve got any additional history to share, please do so in the comments. This account only begins to scratch the surface of the long and complicated history of this part of town.

* While Nulu was once part of Phoenix Hill—as is the block across from Slugger Field—it has taken on its own identity as a place distinct from Phoenix Hill, which stretches south and east all the way to Broadway and Baxter Avenue. We do not consider nor describe the two as the same neighborhood.

Excellent article Brandon. I’m considering moving my family to Louisville from the west coast and I’m soaking up as much info and history of the city as I can. Thanks for providing such detail and insight here!

So Liberty Street was originally meant to be Green Street because it was originally reserved as a park band for the city. This makes me wonder if maybe a park of some sort might be a good idea for a long term use of the ReSurfaced footprint? It seems like a decent place to bring some intentional green space and community space into the core of Phoenix Hill/NuLu. (Our one way streets there would make it a dangerous park, but that might help own that conversation.)