This week, the clock began ticking on a 30-day waiting period before Spalding University can demolish the former Puritan Uniform Rental complex at West Breckinridge Street and Second Street. While there’s good reason to believe an effort to save the building could spare SoBro yet another surface parking lot, the future is still far from certain. History tells us as much.

Modern preservation policy has been made, and somewhat unmade, at and around Spalding University as the institution and its neighborhood have struggled to come to terms with how SoBro should take shape over the past thirty years. There have been dynamic forces at play—an institution in need of growth and a neighborhood caught in between development pressures—that have shaped this relationship.

Spalding is, for instance, the reason we have a 30-day waiting period when someone wants to demolish a National Register–eligible building. There have been several contentious fights over the years that involved university leadership, mayors and top city officials, concerned neighbors and preservationists—and some embarrassing failures to compromise.

The story of Spalding University’s campus and its neighborhood is in many ways the story of preservation in Louisville. Understanding that history is crucial for creating a better SoBro—and a better city at large.

Spalding is certainly not to blame for the cratered SoBro we know today—many hands are shaping this story—but the university has played a part. While there are many differences between the ’80s and today, there’s also much the same, as the timeline below demonstrates.

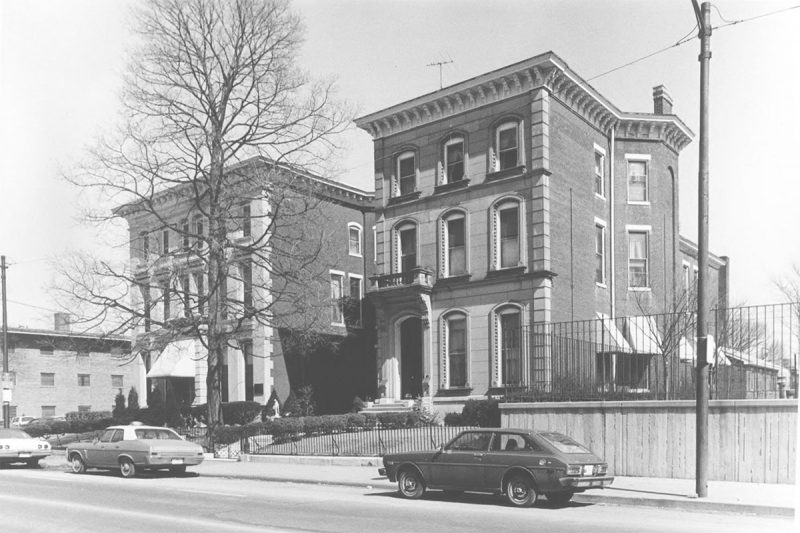

1988: Porter–Todd House, 929 South Fourth Street

On Saturday, May 21, 1988, an article in the Courier-Journal ran with a photo of a partially demolished Italianate house at 929 South Fourth Street, just south of West Breckinridge. Anger was in the air. “It is disgusting for an institution of education to have such a total disregard for a neighborhood and a landmark,” Paul Porzio, a past chairman of the Old Louisville Neighborhood Council, is quoted.

Spalding officials claimed the so-called Porter–Todd House “had no value” but the 1869 structure was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. No use for the site was determined, but Spalding wanted the 2.5-story house and its unique Victorian cast-iron detailing gone. Spalding President Sister Eileen Egan said the university was preservation-minded because it occupied 851 South Fourth Street, today’s Spalding Mansion Complex.

But the university had done nothing wrong in beginning demolition on the house. Back in those days, all you had to do was get a demolition permit and start hacking away. As we’re still very familiar today, listing on the Register doesn’t protect a building, it only helps with tax credits if an owner wants to keep a structure. Then as now, the building would have had to be located within a Landmarks District or declared an Individual Landmark to be given any protection.

Unlike today, however, preservationists like Betsy Hatfield, director at the former Preservation Alliance, had no idea the building was even being considered for demolition. By the late ’80s, wrecking crews tearing away at the city’s historic fabric was a common sight, but city and preservation leaders typically saw it coming and sometimes compromises could be made. The sour taste left by the Porter–Todd House would send ripples through preservation policy in the city.

1994: McAuley Houses, 959–961 South Fourth Street

While the Porter–Todd House was already gutted, it did raise the flag that Spalding had plans to raze two more significant houses on the same block—and the preservation community wasn’t sitting idly by. Next up were the Cornwall and Brown Houses, located at 959–961 South Fourth Street, just south of Spalding’s Morrison Hall dormitory (aka the McAuley complex). Both buildings were listed on the National Register in 1979.

Spalding agreed to work with the city’s office of economic development (today’s Louisville Forward) to try to find a buyer or use for the two houses. After issuing an executive order temporarily banning any wrecking permits for the houses, Mayor Jerry Abramson sat down with Sister Egan and Spalding trustees to discuss saving the buildings. The mayor got the university to wait 30 days before proceeding with demolition work.

The public was in favor of saving the structures and more than 500 people had signed a petition against demolition and for a new law to protect the city’s historic structures listed on the National Register. Spalding wanted to use the land as green space, according to news reports at the time.

In the end, sweeping reforms that would have given real protection to Louisville’s built environment were passed up in favor of the quick, easy fix. The city opted to implement a 30-day waiting period for demolition permits for National Register–eligible buildings and require public notice in the form of bright yellow “Intent to Demolish” signs. That’s the same policy that still stands three decades later.

Several plans were drawn up by various groups and demolition was delayed, but no sale or plan was finalized. Spalding eventually decided in December 1988 not to tear the houses down. A few years later, the university was back with a wrecking ball.

In the summer of 1993, Spalding was again moving to demolish the houses, this time for a 50-space parking lot required for its new Egan Leadership Center. That move was blocked after the city’s Landmarks Commission voted 5–4 that November to declare the houses Individual Landmarks, which should have been enough to protect the buildings—but wasn’t.

Spalding was required by code to build a parking lot for its new building and the McAuley site is where they wanted it. As a push for demolition continued, the city again made a last-ditch effort to broker a deal that would have traded the adjacent Memorial Park for the houses. Those measures dragged the process into the summer of 1994 when everything fell apart. The houses were razed in ten days that August.

In five years, Spalding, the city, the community, the Landmarks Commission, preservation groups, and the city again were unable to make any plan for the McAuley work, representing a major failed effort for Louisville that served to create tension around preservation and a large parking lot in SoBro. “It’s merely a smack in the face of this neighborhood,” then Limerick Neighborhood Association President J. Deney Priddy told the Courier-Journal.

2006: 836–838 South Fourth Street

Skip ahead a decade and another grand mansion is making way for unneeded open space on Fourth Street. A rather unique structure at 836–838 South Fourth Street underwent a rather unfortunate renovation in the 1950s no doubt an attempt to make the structure more relevant in the Atomic Age. The elegant brick structure seen in 1951 with a large tree in the front yard is, by 1955, showing a more streamlined facade and a drab coat of white paint[Note]Photos noted as courtesy UL Archives – Reference, Reference.[/Note]. The large tree has succumbed to a parking lot. This new look gave the former residence a distinctly more commercial / institutional appearance.

The site was known for decades in the 1960s and ’70s as Greenups Belles & Brides, or as advertisements declared, “The big white house between York and Breck.” Before the end, the structure was Spalding’s Joseph E. Kutz International Center, also housing the Louisville International Cultural Center (LICC). The 22,000-square-foot Kutz Building was demolished by Spalding in early 2006. The most recent view above is from 2003.

Today, the site, labeled as “Kutz Park” on Spalding campus maps, is nothing more than an unfortunate missing tooth in a neighborhood in need of dentures. A labyrinth was later installed, giving the parcel some semblance of a space where one might go to enjoy the outdoors. The sidewalk here serves as a continuous curb cut for a parking lot that removes any sense of civic ambition for the green space.

2010: Old Spalding Gymnasium

Until quite recently, the north side of West Breckinridge Street between Third and Fourth streets had a continuous street wall representing a diverse mix of styles and ages of buildings. The overall effect was a handsome arrangement that framed Library Lane and elevated the overall streetscape. On the interior of the block, the gym helped to define several nicely scaled modern courtyards that provided cloistered seating areas for the Spalding University library.

But then the university decided it no longer had a use for an old Romanesque gymnasium at the site. Demolition notices appeared in January 2010, and Spalding officials told Broken Sidewalk at the time plans were to use the site as some sort of green space. The overall sentiment was that the building had become obsolete and was no longer needed, and little thought appears to have been given to the structure’s role in the urban environment.

That June, a “farewell party” was held and by August the gym had been removed for a patch of grass and an awkward gazebo. Broken Sidewalk documented the process throughout the summer.

2012: 318–320 West Breckinridge Street

Spalding continued its swap of historic fabric for green space with the demolition of two more century-old buildings across the street from the Old Spalding Gym. This time the plan was to create a formally arranged green space called Mother Catherine Spalding Square.

While Mother Catherine Spalding Square, dedicated in October 2013, ended up creating a lush central quadrangle with honorable green infrastructure value (MSD chipped in almost $500,000 in “green incentives” for the project), demolition of contributing structures like the two at 318–320 West Breckinridge or the Old Spalding Gym are frowned upon by the SoBro Planned Development District plan completed in 2011.

“Existing structures that are identified locally or nationally as having significant historic character should be retained and incorporated into new development rather than torn down to accommodate new development,” that plan reads. It specifically stated National Register buildings, which all three would have been eligible (although not listed), were to remain. “Demolition of such designated structures, shall not be permitted for the creation of surface parking lots or open space.”

Spalding officials said at the time the square would be a “much better use” of the land than keeping the buildings.

2016: Puritan Uniform Rental Complex

We’ll have to wait and see for now what becomes of this one.

Awesome, if depressing, walk-through. Good to know the history of Spalding’s actions since I’m new to the neighborhood (Limerick). Hope to see a better future for the Puritan Building. I bike past it almost daily and can’t imagine another parking lot in the area.

And the destruction continues. Can we expect any protection from Landmarks? Nope. P&Z? Nope. Metro Council? Nope. In addition to Spalding tearing down buildings for open space, it has blocked public use of the alley running North from Kentucky Street between 3rd and 4th. Better not complain when I drive through your parking lot, Spalding!

What about the interesting brick warehouses cleared for Spalding’s sports fields on 8th St? Was that clearing work already done before Spalding made the deal to buy it, or done for the purchase?

If they want a suburban campus, move to the suburbs… Spalding hardly brings an influx of residents to the area. I may be wrong, but I’d wager the vast majority of students and faculty still commute, and when you provide those commuters an adjacent parking lot for their car, they don’t have any reason to stick around and patron any businesses. Drive to class, drive home. I’m not sure if the leadership there wants the university connecting with the neighborhood around it. The more parking lots and open spaces they create, the more isolated and “traditional” they can make their college experience. But Spalding isn’t Bellarmine up on a hill, it’s an urban campus that needs to start embracing it’s unique opportunities instead of tearing them down. Higher learning, indeed. *le sigh* thanks for the read BK!

FYI, the before/after widgets don’t seem to be working for me.

Thanks for the heads up, Jeff. Should be fixed. Was doing some technical work over the weekend and that slipped through.

What can we do to help save the Puritan building??

please, do not forget to include the entire C. Lee Cook complex on 8th @ Kentucky that was demo’ed by Spall-Ding for their ‘athletic fields’ that aren’t being pay for by anyone.

To be fair, Spalding did not demolish the C. Lee Cook complex, they purchased the cleared site. The block was demolished by Cook Compression / Dover Corporation in an attempt to make the property more marketable. Here’s our story from 2012: http://brokensidewalk.com/2012/demo-watch-eighth-street-warehouses-threatened/