Demolition has begun on the old Louisville Water Company Building, a complex of four buildings that will be removed for the planned Omni Hotel & Residences. Wrecking crews were spotted on site on Monday, tearing away at the back of the complex of buildings. Since Mayor Greg Fischer filed for demolition permits on August 6, readers were a bit concerned about why demolition work began ahead of the 30-day stay-of-demolition associated with National Register–eligible buildings. Demolition, according to the permits, could not begin until September 6.

Cynthia Johnson, Historic Preservation Officer at Metro Louisville, explained why the work was proceeding this week. She told Broken Sidewalk that the two garage structures on the back of the Water Company complex had been declared “non-contributing” by a study of Downtown’s built environment by John Milner Architects.

“It’s not just age that determines if a building is historic or not,” she said. These garages appear on a 1941 insurance map that indicates they were built in 1915. The two-story and three-story buildings have their own brick facades facing a sort of courtyard at the complex. “[John Milner] evaluated their eligibility status [for the National Register], and the back additions were determined to be non-contributing,” Johnson added.

According to Metro Louisville’s wrecking ordinance (150.110):

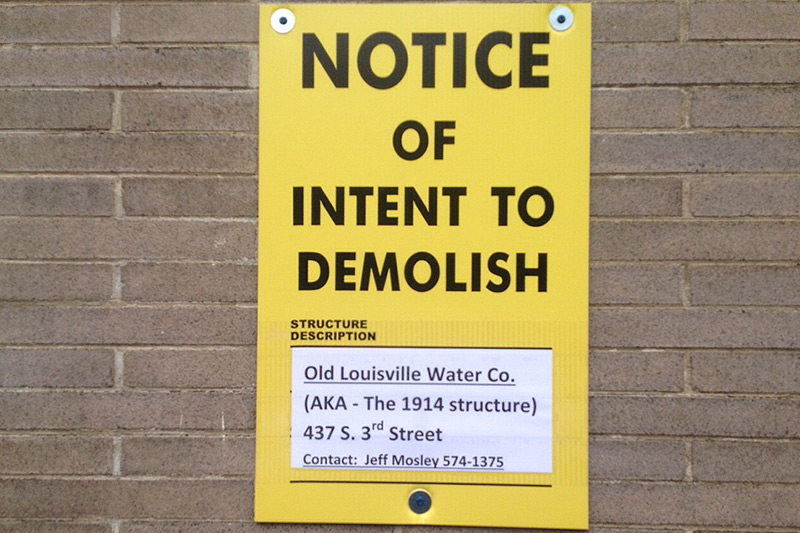

Work on the two older pieces of the Water Company Building complex, dating to 1910 and 1914, cannot proceed until September 6. In the past month, however, crews from Louisville-based National Environmental Contracting have been inside all portions of the complex removing asbestos prior to demolition.

Several concerned tipsters wrote in recently describing the poor treatment of the building during this asbestos abatement period and prior. Photos taken from February inside the building show a dirty scene, but an otherwise architecturally intact ground floor lobby. Visible are the building’s original mosaic tile floor, ornate walnut paneling, and detailed teller windows. At that time, sources with access to the interior said the building was in stable condition and generally water tight.

Four months later, the building was beginning to crumble, suffering from water damage with ponding on the floor—a rather substantial shift in such a short time. Now only the floors remain intact, one tipster reported, with some tiles chipped and marred. Another source speculated that this interior damage could jeopardize acquiring historic tax credits necessary for a potential move of the building, as several citizen-led initiatives hoped to do.

The Fischer administration rejected three proposals to move varying portions of the building earlier this month, but some believe there’s still a chance to salvage all or part of the building. Fischer said he plans to put the front part of the oldest structure in storage in September. We’ll have more on this aspect of the demolition in a later article.