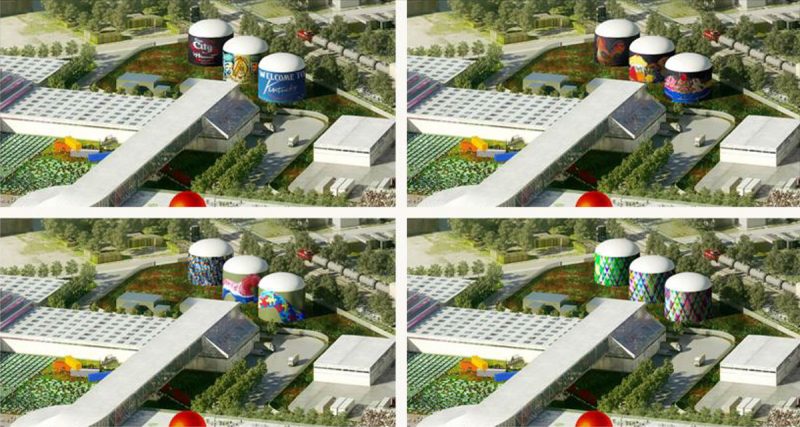

In early 2015, a major development—the West Louisville FoodPort—was announced in the Russell neighborhood that promised internationally renowned architecture, a hub for local agriculture, clean energy, new jobs, and public spaces. The project garnered glowing international attention for its design and ambition. But for local residents, there appeared to be a fly in the ointment.

Tucked behind the FoodPort’s zigzagging edifice, a series of cylinders rendered with bright paint would have housed a methane power plant capable of turning organic waste into fuel.

Indiana-based STAR BioEnergy (formerly Nature’s Methane) had partnered with the FoodPort in the early stages of the project, proposing the construction of anaerobic bio-digesters that would convert organic waste into biogas (methane or carbon dioxide) and fertilizer.

Community leaders raised flags about that component, citing public safety fears for residents in a part of town overburdened with industry.

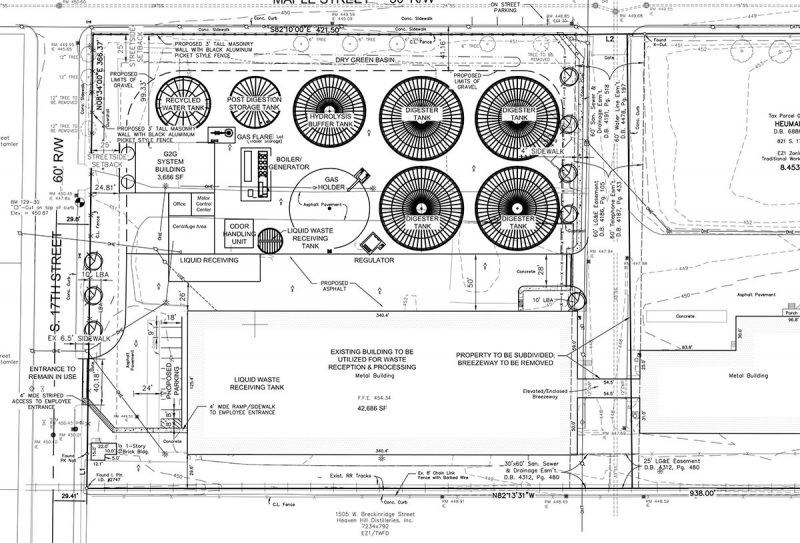

As summer progressed, STAR BioEnergy announced plans for a second digester plant in the California neighborhood at 17th and Maple streets. The goal was to convert bourbon stillage from the adjacent Heaven Hill Distillery into methane gas. That plan would have brought a 44-foot-tall chemical tank to the middle of a predominantly residential area, raising more flags for West Louisville leaders.

According to Mark Stoermann, the company’s chief operating officer, densely populated areas were actually ideal for digesters of this type. Instead of trucking in fuels from outside sources, Stoermann said local communities could obtain energy directly from the digester, resulting in fewer carbon emissions.

California residents made it clear that they weren’t against the waste-to-methane technology, but just the proposed placement of the digesters. Community leaders throughout the city came forward and advocated for the people of California, agreeing that a development like this simply did not belong in a residential area.

A report from the Courier-Journal later pointed out that although STAR promised to obtain at least 70 percent of the waste from Heaven Hill Distillery, it would continue ship in 15 percent of its organic material from outside sources—up to 10 trucks per day—which disputed Stoermann’s previous suggestion that the digesters would help reduce emissions caused by fuel trucks.

Objections continued to pile up until late summer 2015, when the FoodPort ultimately scrapped STAR’s plans for the digesters. “Certainly STAR did not want us to remove them from the project when we did so in August,” FoodPort backer Stephen Reily wrote Broken Sidewalk in an email. “Our rationale for doing so [was] respect for what the people of West Louisville want and don’t want in their neighborhoods.”

Still, the company pressed on with the Heaven Hill site project.

That decision only intensified protestation from residents and their allies, who urged the company to reconsider the location of the waste tanks. Instead, company leaders held a series of meetings aimed at “educating the residents” on the science behind biodigesters, insisting they were safe to use in residential zones.

Hoping to quell community concerns, STAR announced in November that it would funnel $5 million to the California neighborhood and Simmons College for educational programs in the community. Mayor Fischer touted the agreement as something of a bargain for West Louisville, and promised that the funds would be distributed by a “group of community leaders.”

What was perhaps a well-intentioned attempt to gather support for the project came across to many as legal payola. Protests continued as more and more people came out against the entire project, including Metro Councilmember Mary Woolridge (D-3), who said that such an agreement “fuels the ongoing belief that backroom deals can buy and elevate leaders.”

At one point at the end of 2015, Councilman David Tandy proposed an alternate site at the city landfill for the biodigester facility. Also in December, STAR revised its plans, announcing an even more robust venture.

Then in January 2016, Insider Louisville reported that the company would buy the site and push ahead with the project. That report listed the plans that Steve Estes, CEO of STAR, had for the property: develop an office space, a solar array, and a 40,000-square-foot aquaponics facility that he hopes to develop through a partnership with Kentucky State University’s aquaculture program.

According to journalist Caitlin Bowling, Estes was looking into buying up more empty commercial buildings along the Maple Street corridor, and still hopes to construct a biodigester somewhere in the city—either in California or elsewhere—but that he would be willing to scrap the idea altogether as long as the community remained opposed to it.

Ultimately in late February, the Louisville Metro Council voted to institute a six-month moratorium on issuing permits for biodigester construction projects in Louisville—at least until further studies could be conducted on their potential impact on public health and the environment.

Mayor Greg Fischer supported that idea, releasing the following statement:

I support a temporary moratorium until we, as a community, decide where in the city biodigesters could be built. Biodigesters are a proven and safe technology used worldwide and having a clear understanding of the ground rules for constructing them in our city is a prudent move.

Still, some in the neighborhood have vowed to continue fighting alternative sites for biodigesters.

Now, after more than a year of political wrangling, many are left to wonder what the future holds for digester technology in Jefferson County. If there is a lesson to be learned, it’s that this experience demonstrates the disadvantages associated with top-down community development.

Despite the fact that anaerobic digesters are viable green technologies, the underlying problem remains that residents were never involved in the overall discussion of how this project could have taken shape—it proceeded as though the solution to their problems had already been decided.

Perhaps Allan Latts, chief operating officer at Heaven Hill, said it best: “We recognize that the concerns we heard at that meeting had to do with more than just building a digester. It has to do with a legacy of being overlooked and disrespected in West Louisville. Trust now needs to be rebuilt.”

[Correction: An earlier version of this article stated that STAR BioEnergy pulled the biodigesters from the FoodPort plan, when it should have read that the FoodPort pulled that component while STAR wishes to stay on board. This article has been updated.]