One of the two main goals of the Move Louisville plan, the city’s 20-year transportation plan, is to reduce the number of miles people drive each day. The plan calls for reducing Vehicle Miles Travelled (VMT) by 500,000 per day, which might sound like a lot, but is really only a tiny sliver—2.6 percent—of the overall daily miles traveled.

Still, it’s important to start somewhere, and in the case of Louisville’s quite strong addiction to the automobile, that might require some baby steps.

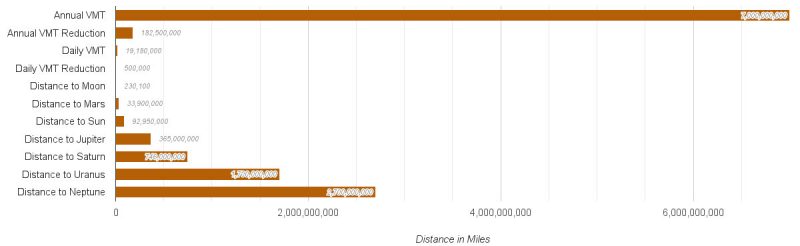

In our longform analysis of the plan, we put the astronomical number of miles Louisvillians drive into orbit by comparing them to the distance between the Earth and the Moon—230,100 miles. But that distance turned out to be far too small to measure the total distance Louisville drivers tally up annually. We’re talking 7 billion miles driven by Louisvillians each year! So we upped the ante and went interplanetary.

Above are some comparisons to put just how much Louisville drivers hit the accelerator each year in perspective, measured by some of the farthest out-there planets in the solar system.

But in all seriousness, Louisville’s VMT challenge is a significant one. And it’s one with a lot of low-hanging fruit that we can use to get some immediate, noticeable results.

According to Move Louisville, for instance, 50 percent of all automobile trips made are three miles or less, with 28 percent of trips being a mile or less. Those trips, especially in the latter category, should not involve driving an automobile. The challenge, of course, is getting people out of their cars for these short trips. And it’s not an easy one. First of all, the vast majority of the city is not built for walking or biking. For Louisvillians who live in the suburbs, trying to walk to a corner drug store often means taking their lives in their own hands. Speeding traffic along arterial highways, few crosswalks, and often missing sidewalks make walking deadly even if it’s convenient.

It’s a sort of chicken and egg scenario: what comes first, getting people out walking or building safe walking infrastructure?

We’ve certainly got a lot of walking infrastructure work we’ve been putting off, too. We often hear groans from motorists and local politicians about the state of our streets, and they’re certainly not in the best shape. (According to the city, it will cost $112 to repair the 30 percent of city streets rated as deficient, with another $27 million required to rehab bridges and culverts.) But to fix Louisville’s sidewalk network, Move Louisville notes, it will cost far more: $86 million is required to repair ten percent of the city’s existing 2,200 miles of sidewalks and another $112 million to fill in gaps in the sidewalk network

It makes sense to begin looking for VMT decreases in the more walkable urban parts of the city, where many people are already out walking and the infrastructure is significantly more complete. A bit of education could help remind people that it’s worth leaving the car behind for short trips—sometimes, after all, we just get into a habit like driving and get stuck on autopilot and end up driving everywhere. A few reminders that our feet still work could go a long way.

But we’re going to have to face the challenges of the suburbs and exurbs at some point, and this is where transportation planning and land use planning collide head on. We can’t continue to build unwalkable housing subdivisions and strip malls that require car ownership to participate. Better thought of the built environment is necessary, will require strong city leadership, and will likely not be very popular at first, especially among a development community that’s been building this way for so long.

These hard choices are becoming increasingly important, as data from Move Louisville makes all too clear. The plan documents that challenges Louisville is up against, and the future competitiveness of the city is at stake.

Move Louisville puts data behind what we already know: Louisvillians drive—a lot. “In comparison to our regional peer cities and the nation, Louisville’s percentage of residents driving to work alone is high,” Move Louisville reads. Almost 82 percent of Louisville’s 344,000 workers drive to work alone each day. “For example, 72% of Cincinnati’s residents drive alone, while Nashville’s and the nation’s rates stand at 80% and 76%, respectively.” Some 89 percent of Louisville households have one or more automobiles.

And while car ownership rates aren’t necessarily the problem, when we make using those cars the most convenient option ahead of all other modes, there should be no surprise that we create a city in which everyone drives.

At the other end of the spectrum, only three percent of people in Louisville take transit to work. That’s only 10,320 people out of Metro Louisville’s pool of 344,000 workers. Locally, ten percent of households do not own a car, making them reliant on transit, biking, or walking.

There’s a clear problem on the streets of Louisville, and it’s not one that’s going to be easy to solve. Even if we want to get out of cars and begin to help solve these problems, it’s often impossible or too dangerous for many Louisville residents. What would it take for you to drive less? To walk or bike for short trips? Or to even try using transit a couple times a month? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

I strongly believe that more people would be happy to live downtown or significantly closer to downtown if we didn’t have a mess with the school system. JCPS schools and their policy around buses are the reason that my family live in Oldham County. If we could live downtown and know exactly which school we would be going to, we would certainly look at the move downtown.

We are actively looking at opportunities to move to cities that are bike and walking friendly. We would like to get rid of one if not both of our cars and take trains, bike or walk to work daily. Another item that may help get people driving less is a the use of a metro rail system. We should have not done the Ohio River Bridges project and put that 2 Billion towards a light rail system instead. The cities that are poised for strong economies and easier growth are those that have light rail systems. Look at Nashville, that city has exploded in growth and is plagued with issues due to its dependence upon driving. Louisville will be there in another 10 years if we don’t do something quickly.

All of this x1000! Thanks, Branden, for so eloquently explaining so many of Louisville’s problems. I agree with Justin in that the school system/busing are definitely a challenge to that portion of the population that to which it matters but what about all of those millennials and empty-nesters who don’t have to worry about schools?

Was living in the most notorious car-culture of Los Angeles, driving for everything. It was really draining, but the distances for my jobs were so great that biking and transit were not even options.

So, when I came back to Louisville this summer, it was really important to me that I build a more compact life. I moved to the Highlands, got a job around the corner, made some good friends in the neighborhood, and now the only time I drive anywhere is to do laundry at my mom’s house…

There’s no frikkin’ way that more than just a handful of people who live in Oldham or far eastern Jefferson would live downtown or in one of the closest neighborhoods if JCPS had a simple neighborhood based attendance zone policy. Because the schools nearby would be filled with the kids they are trying to avoid by living where they do now. The Highlands is as close as they’d get.

My personal contributing irony is that I live downtown but have yet to work for a company with offices downtown, or where work from home may be the rule rather than the exception.

Also, for a lively late night city, TARC doesn’t seem to like operating outside daylight hours. I realize there are catch-22s in getting enough ridership to justify later hours, but a part of why people don’t “trust” TARC to be timely/available in daylight is because they know they can’t trust it in the evenings to get home from a nice dinner and conversation. No one can take the TARC to a Yum Center event or a Slugger Field game or a Headliners show and expect to take the TARC home (not even Downtown residents).