(Editor’s Note: Yesterday we looked at how Louisville stacks up nationally in terms of bike ridership and infrastructure. Part of that involved suggestions from leading bike groups that the city implement better designs on its new system of protected bike lanes. Here are a few examples of top protected bike lanes from across the country.)

If 2013 was the year protected bike lanes went national, 2014 was the year they got beautiful and 2015 was the year they got durable, 2016 has been the year they did something even more valuable.

They started to connect.

From Atlanta to Chicago to Seattle, protected bike lanes intersected. For the first time this year, the leading cities weren’t just closing bike lane gaps (though they were). They were also starting to form grids.

Almost exactly 100 years after American transportation was revolutionized by the build-out of a different vehicular grid—these days most people refer to it as “the road”—the country’s gradual investment in all-ages bike lanes is finally becoming an investment in all-ages bike networks.

In recognition of that and of the new phase of our work at PeopleForBikes that’ll help cities prioritize and complete gaps in their developing bike networks, we asked the experts who advised us on this year’s fourth annual list of the country’s best new bike lanes to put extra emphasis on the role projects played in their city’s network.

Here are the nation’s best new connections.

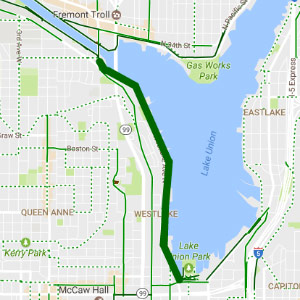

1) Westlake Avenue, Seattle

The country’s best new bike lane of 2016 is a stripe of asphalt evidence that Seattle is willing to explain, over and over again, why a parallel route two blocks away sometimes isn’t good enough.

No one who’s actually ridden a bike in Seattle’s near north side would confuse Dexter Avenue, with its 300-foot climb, with the lakeside bend of Westlake Avenue just to the east.

Fortunately for Seattle, its leaders knew the lay of the land. So they soldiered through years of negotiations and lawsuit threats to finish Westlake, finding a design that preserved 90 percent of the spaces in a relevant public parking lot. The turning point: Mayor Ed Murray called all parties into a room and forced them to hear one another out.

“If you never sit down and talk to the people who are on the other side of the table, you’re going to invent reasons to disagree,” Seattle Transportation Director Scott Kubly said Tuesday. “When it gets right down to it, most people wanted the same thing.”

What they got was a world-class bikeway: the first flat, intuitive link joining downtown Seattle to the north side and a vast regional trail network.

2) Randolph Street, Chicago

Seattle and Chicago are the only two cities whose projects have landed on this this list four years in a row, but it’s Chicago that continues to deliver first-in-the-nation designs—and also, as it happens, some of the country’s most consistent growth in bike commuting.

Two eye-catching protected intersections along Randolph, where the new protected lane crosses existing bikeways on Canal and Dearborn, are the first in a major U.S. downtown.

Even more exciting to our experts, though, was the fact that Randolph links Dearborn (our #1 lane of 2013) with Clinton (our #10 lane of 2015), making both of them twice as useful. Randolph will get even better this spring when an extended buffered lane on Washington, one block south, creates an east-west couplet—enough for us to forgive Randolph’s unfortunate one-block detour onto the sidewalk.

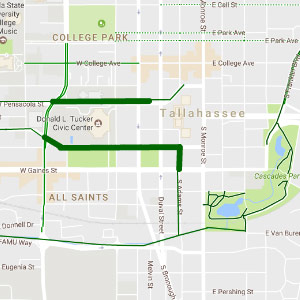

3) Downtown-University network, Tallahassee

Tallahassee planner Artie White isn’t sure what the thinking was that once led his city to turn the two main routes between Florida State University and his city’s downtown into one-way speedways.

Tallahassee planner Artie White isn’t sure what the thinking was that once led his city to turn the two main routes between Florida State University and his city’s downtown into one-way speedways.

“If you want to take the life off of the street and have it as a place that you drive through instead of driving to, sure maybe,” he said. “But that’s not what we wanted to do with our downtown.”

So this year Tallahassee started calming these streets (which run on either side of Florida’s capitol building) by adding protected bike lanes instead — and threw in three other short segments that connect the system directly to the 16-mile St. Marks Trail to the Gulf coast. Look for the number of bicycles transported through Tallahassee by car-top roof rack to plummet in the next few years.

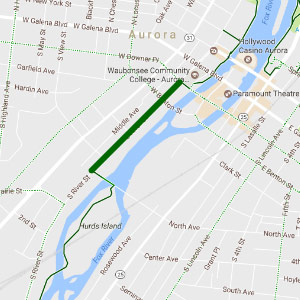

4) River Street, Aurora

The second-biggest city in Illinois is accustomed to life in the shadow of the biggest one, 40 miles to its east. But Chicago has nothing like the Fox River Trail that runs through the western collar counties.

The second-biggest city in Illinois is accustomed to life in the shadow of the biggest one, 40 miles to its east. But Chicago has nothing like the Fox River Trail that runs through the western collar counties.

For years, the only flaw in the trail’s 60-mile span (intersecting with several other paths) has been a one-mile gap near central Aurora — until last spring, that is, when the city unveiled a new one-mile curb-protected bike lane that brought everything together, complete with green paint and bike-only signals.

“We knew it would benefit not just bicyclists, but our residents and businesses as well,” Mayor Tom Weisner said in September. Party on, Aurora.

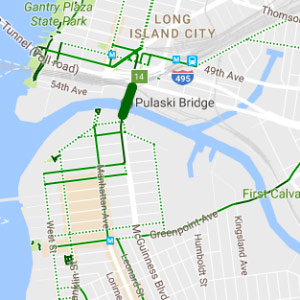

5) Pulaski Bridge, New York City

If they were to jointly secede from NYC, Brooklyn and Queens would create the country’s biggest city.

If they were to jointly secede from NYC, Brooklyn and Queens would create the country’s biggest city.

The two boroughs are separated by Newtown Creek, an industrial channel with just two bridges in a two-mile stretch. One of those bridges, Pulaski, has long forced people walking and biking into the same narrow, crowded shared path.

Until this year, when the boroughs were stitched closer with a first-rate project that repurposed an auto travel lane to finally give bikers and walkers their own spaces, separated by concrete. And it’s built on a drawbridge, no less. If NYC DOT can keep delivering projects like this, maybe Brooklyn and Queens will keep letting the three smaller boroughs hang out with them.

6) Telegraph Avenue, Oakland

When NYC DOT’s Ryan Russo visited Oakland in 2014 to check out its plans for Telegraph Avenue, he had one question: “‘Why did you pick such a difficult street to do your first protected bike lane?”

Five lanes plus parking, lined by shops and busy with buses, Telegraph got its name because it’s always been the shortest line between two cities that are now among America’s bike capitals: Oakland and Berkeley. Few streets in the country have more long-term potential as a bike thoroughfare. That’s what led advocacy group Bike East Bay to go all in, knocking on the doors of every shop on the street and selling two business associations on the concept. They also created a huge on-street demo that helped persuade skeptical bureaucrats that it’d work.

The nine-block stretch that opened last spring still needs improvements — floating bus islands, for example, are funded but unbuilt — but with $9 million already lined up for the next two extensions, Telegraph now has momentum to become one of the country’s best streets for people.

7) 15th Street NW, Washington DC

Some bike lanes exist mostly to save space for better ones in the future. That was maybe the best that could have been said for the truly odd design of DC’s 15th Avenue between V and W streets before the city gave it the major upgrade you can see above. We’ll let the Washington Area Bicyclist Association (WABA) do the talking: the new concrete curb and bidirectional bikeway here turned the intersection “from one of the most crash-prone in the city to a model example of a complete street.”

If a network is only as comfortable as its weakest link, fixes like this one are the sort many cities need most.

8) Franklin Avenue Bridge, Minneapolis

The longest concrete span bridge in the world when it was built in 1923, the Franklin Avenue Bridge is a crucial link across the Mississippi just southeast of the University of Minnesota, joining two sections of the Twin Cities’ legendary network of off-street paths. By narrowing the auto travel area across the bridge, Hennepin County made room to move the conventional bike lanes behind a curb and rail. On the day it opened, residents from each side of the bridge dressed in their neighborhoods’ official colors and had a party together on the top.

9) Maryland Avenue, Baltimore

This project is the opposite of the last two: instead of closing a small gap in an existing network, Baltimore this year began a new network in a big way. Once the city can add some limbs to this huge 2.6-mile bidirectional trunk between Charles Village and downtown, it’ll be building a Baltimore that’s significantly easier, cheaper and healthier to get around.

10) Cass Street, Tampa

Biking has vast potential in the nation’s third-largest state, and this connection between the Ybor City district and the north side of Tampa’s downtown shows a Florida city building its most important bike routes first. Though overly restrictive federal bike-signal regulations may have forced a flawed signal setup on Cass, the project stands out for its importance to the future network and for the fact that it’s already helped prompt a likely follow-up project on the parallel Jackson Street — a state highway. When your project is helping get a state DOT rolling on protected bike lanes of its own, you’re doing something right.

(Editor’s Note: This article has been cross-posted from PeopleForBikes’s Green Lane Project blog. Follow along with PeopleForBikes on Facebook and Twitter.)