Smoketown is in the middle of a dramatic transition. The Sheppard Square housing projects are being replaced by a new mixed-income neighborhood, individual houses are being rehabbed throughout the National Register historic district, and new investment like the YouthBuild offices are popping up on the neighborhood’s main drags, Shelby, Preston, and Logan streets. With its location between Downtown, Nulu, and the Medical Center on one side and Germantown and the Highlands on the other, Smoketown seems poised for new growth.

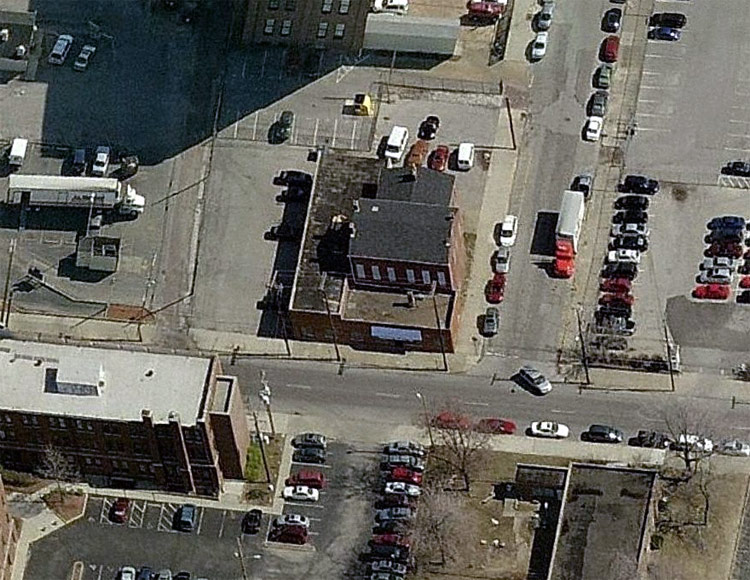

Even with positive happenings all around, some of the neighborhood’s oldest buildings are falling through the cracks. Such is the case of a vacant two-story duplex townhouse dating back at least to 1876 at 721 South Preston Street on the corner of Jacob Street. Look closely or you might miss the historic structure behind a modern commercial addition that last housed the now-out-of-business Harrison Medical Supply.

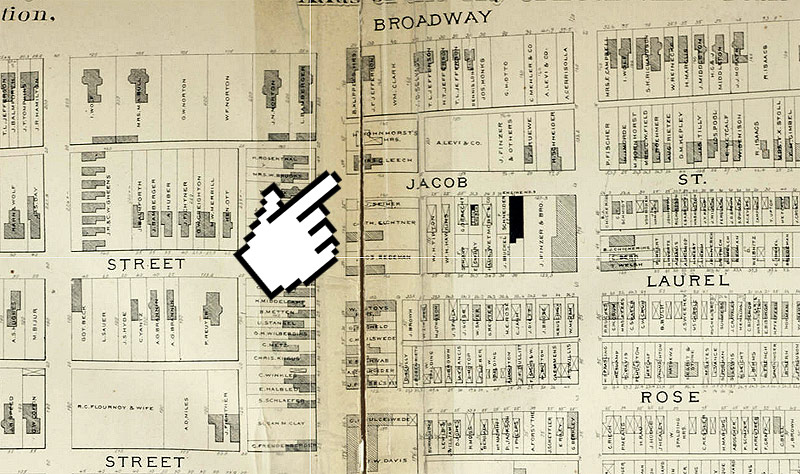

The brick townhouse is simple in form and one of the typical mid-19th century dwelling types in this part of Louisville, along with the predominant shotgun house. The structure sits just outside of the 78-acre Smoketown National Register District, roughly bounded by Preston, Caldwell, and Jacob Streets, and an alley east of Shelby Street. The townhouse appears on the 1876 Louisville atlas (below), but likely is older. Judging from the atlas map, this structure is one of only four remaining from the era in an eight-block surrounding region. According to National Register documents:

The earliest houses were probably built as farm dwellings between 1830 and 1855, when the area was still basically rural. No trace of these rural dwellings has survived in Smoketown, and therefore, the oldest surviving structures are ones that date from the early years of dense residential development in the area during the years 1855 to 1865.

The structure sold in June for $175,000, below the asking price of $295,000 as listed by Hoagland Commercial Realtors. The listing indicated the building has 6,060 square feet, includes adjacent surface level parking, and warehouse space in the back of the addition.

The new owner, a doctor from Prospect, purchased the house under Cardinal Ventures, LLC and has since filed for a demolition permit, which can be issued on August 22. As is typical for buildings of this age, a 30-day stay of demolition is required. The lawyer representing Cardinal Ventures declined comment and the owner could not be reached for comment on any future plans for the property.

Is it possible that the new owner wants to only demolish the newer commercial store front?

It’s possible, but I’m guessing unlikely. Complete speculation, but given the quick time that the LLC was formed, purchased the structure, and applied for demolition, and that it’s a doctor and the site is across Broadway from all the hospitals, it could be either an investment site for a medical office building or the site for a new building. At any rate, the owner did not respond to a request for comment, so it could be anything.

@Branden Klayko – Unfortunately, that makes too much sense. I hope in the very least that the good doctor has the sense to use good urbanism when designing his new building. But why do I get the unpleasant sensation that such a thought is just more wishful thinking?

Screw any sense of “good urbanism” which is usually doublespeak for “I know way better what to do with your property than you do.”

I live right next door to this structure. Tear it down. Immediately. It isn’t worth saving in the least. It’s structurally dodgy and serves only as a repository for graffiti and vagrants. We really don’t have to pack-rat old buildings like this one.

This building, whether deemed “worthy” of saving or not (certainly appears worthy, as outlined in the post…), sits in a sea of asphalt. WHY must we tear down to create space when there is already so much unused surface-level parking that could be used for development? How do we honor individual property rights while promoting urban infill (see also the St. Francis expansion). How do other cities do it? Tax incentives? Do any of you more-knowledgeable urbanists have a good solution to this? (I’m just a concerned citizen and don’t know all the ins-and-outs to these issues).

@Bryan Grumley – Bryan: “we” aren’t tearing it down. “We” aren’t doing anything. The owner is tearing it down. Which is his right. Because he owns it. “Owns.” If “we” wanted it to sit there and crumble in some misguided sense of preserving it (which to me seems like preserving an old shoe… it’s hideous) then “we” should have ponied up the cash and bought it. But “we” didn’t.

@Aaron – Point taken. That’s why I mentioned honoring individual property rights.

@Aaron – Unfortunately Mr. Aaron, when it comes to “good urbanism” there is no double speak. In fact, its one of the most black-and-white issues out there. I’m not saying the guy should “pack-rat” the building, because in its current condition it indeed looks terrible and needs a lot of work. But I just can’t agree with this knee-jerk reaction of “ITS OLD!! AHHH! TEAR IT DOWN!!!” so many Louisville developers seem to get when it comes to boarded up historic structures. Even I can remember when East Market Street was nothing but a deserted row of commercial buildings in similar condition to the property in question; I shudder to think what it would look like now if Gill Holland and friends had a similar attitude. But if he is going to tear down a 136-year-old house, thats fine; as long as good building that enhances its urban environment replaces it (buts let be honest, its gonna be parking for the next 2-5 years). By that I mean one that acknowledges the fact that its in an urban neighborhood close to the heart of downtown (multiple stories, built right up to the sidewalk, etc.) You are correct in stating that it is his property, and its ultimately up to him in regards to what he does with it. My point is that he should realize that he lives within a community, and that his actions will have an impact on it.

While it’s often convenient to shout down preservation with the “If you wanted it preserved, you should have bought it” arguement, as was used by Todd Blue in his recent attempt to tear down Whiskey Row, it’s more useful to look a little closer at the purpose of city regulations and why they’re put in place.

Cities have a variety of codes and regulations that govern how land and buildings are used. Zoning codes, for instance, can prohibit certain uses from certain areas. If someone wants to build a toxic dump in a residential neighborhood, the “If you didn’t want a toxic dump on this property, you should have bought it” line seems pretty silly. The spectrum ranges from building and fire codes that provide for basic public safety to zoning, overlay, and preservation rules that govern how communities are built, look, and feel. Individual buildings and properties in cities don’t exist in vacuums and can externally affect the surrounding community.

In Louisville, when someone applies to demolish a building old enough/eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, a stay of demolition of 30 days is ordered. That’s the case with this townhouse and with other demolition notices posted on Broken Sidewalk. This 30-day window is intended to provide time for documentation of the building before it’s lost and in more rare circumstances, like what happened at Whiskey Row, afford citizens a chance to mount a campaign to designate a structure a Local Landmark by gathering 200 signatures and paying a hefty fee. That’s what the recent Landmarks Ordinance in Metro Council was attempting to change, making the process even more difficult and giving Metro Council, a political body, the final say over designations. Right now, the final call for establishing a new landmark lies in the hands of the Historic Preservation Commission, an appointed board of professionals able to evaluate a building’s merits as a landmark. Short of designating a building a Landmark, there’s nothing the city can do to stop the destruction of a building like this townhouse.

Some buildings might be worth preserving, but can’t muster support to be declared a Landmark (or rightly shouldn’t be elevated to Landmark status). Other cities have dealt with this issue by implementing a demolition review process that can provide some protection for historic buildings under threat. While I’ll go into the topic in more depth in a full post, the example of St. Louis is a good one: http://www.slpl.lib.mo.us/cco/code/data/t2440.htm

In St. Louis, if a building is listed or is eligible for listing on the National Register or sits in a National Register District, the demolition permit is put on hold for 45 days and the demolition permit applicant is required to photographically document the structure in question. During that time, the city’s Cultural Resources Office or Preservation Board can review the permit application and issue a written opinion to the Building Commissioner. The Preservation Board can then hold a hearing and decide to approve or deny the permit based upon preset criteria such as the condition of the building, the proposed redevelopment plans and urban design, the architectural quality of the structure, its potential for reuse, or the effect on the surrounding neighborhood. These hearings can be contentious, and it’s no guarantee that every historic building will be preserved. There’s also an appeal process built into the system.

Often what results in these cases is the Board will choose to deny the demolition permit until the time that a building permit is issued. That could avoid cases like what happened at the D&W Silks building across from Slugger Field that was demolished for a parking lot that is supposed to give way at some time to an office tower. With better preservation options, Metro Louisville could have conditionally approved the demolition of the structure once the developer was ready to build on the property. A demolition review process also helps cities prevent more surface level parking lots from being built downtown.

Until Louisville gets serious about preserving its history and building stronger, more sustainable communities, buildings like this townhouse and more significant buildings all across the city can be torn down without oversight and with impunity.

@Branden Klayko – Great information. Looking forward to your full post – provides some defense from being “shouted down.”

Don’t come complaining to “US” when the doctor opens a summer camp for sex offenders. Property rights are great, until your property rights are violated by your neighbor. @Aaron –

@Bret – Property rights ARE great. They are the difference between growth, development and new jobs (which is what MY neighborhood in Smoketown desperately needs) and the lackluster half-hearted ambitions of East End, Whole Foods, NPR crowds who constantly assume that… well, they just know better than everyone else and should be in charge.

Because every other day, the same crowd says things like “Oh I don’t go downtown! There’s no where to park! Those one way streets are confusing! And they don’t even HAVE a Banana Republic!”

Property rights ARE great. Hernando de Soto did a wonderful job of explaining why in his book “The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else.” The answer is: valid property rights.

I’m certain that is what’s going to happen. A summer camp for sex offenders. No doubt. Not a new franchise, or a neighborhood health clinic. Dr. Haq has established a fantastic one nearby here. I know, because he’s my friend and my doctor.

Brandon might have put it best when he said: “you might think that preservationists are among the most dangerous groups in town, threatening developers, the community, and all property owners with their willy-nilly attempts to control property rights and adversely affect home values by forcing people to save eyesores across the city. This (only-mildly-exaggerated) assumption…”

It is barely exaggerated. Here is why we always use the argument that if you wanted to save it, you pony up and buy it: Because we don’t want people coming into our neighborhoods and telling us what we can and cant do with our property. It’s nothing less than boring, tired old Occupy-blah blah blah class warfare against people who are successful and who build prosperity in our neighborhoods.

I tell you what. If you can’t actually build wealth or do something constructive, that’s fine. Keep working at Arby’s. But leave the rest of us alone. That’s why I called David Tandy this morning to thank him for voting for the new ordinance. So that people in this neighborhood can have a chance to get new jobs, new opportunity and a hand up into the middle class. Not be stuck in some 19th century ideal of what the city should look like, where everything old is great, and everything new is wrong.

Until you can do that, enjoy your drum circle and leave the productive people alone.

@Aaron – You make some very interesting arguments, Mr. Aaron. Might you be attending the City Suds event at Zanzabar? I would love to discuss this topic further with you in person. Oh, and please bring along one of these “East End Preservationists” you speak of; I’ve never met one before and would love to show them my latest Banana Republic purchases!

I did grow up in the East End, but other than that, you sort of missed the mark. As a registered Republican, I can assure you I have never participated in a drum circle, nor do I listen to NPR, or shop at Whole Foods or Banana Republic. I work for a successful developer in Denver, not at Arby’s. I create more “wealth” and jobs than you likely ever have.

My point was that while property rights are great 95% of the time, not all of us got hit by the Tea Party bandwagon. Just like free speech, there is a time to limit rights if it infringes on other people’s rights or safety. And I’m not refering to the Preservationlists’ rights or yuppies who think it would be better as a coffee shop they can visit on a Sunday bike ride rather than a bike manufacturing company. My point is before you start waving your property rights flag, consider the impacts if this owner decides to pursue something that negatively impacts you and the neighborhood.

Since I do not live in Louisville, I could care less if this building is saved or leveled. But as a developer who previously worked as a public sector planner, I’m aware of the issues when property rights get waved around without any consideration of the alternative. If I wanted to invest in this area, I would have developed one of the over-saturated parking lots ….. not a building that could be put to use by someone else.

@Bret – Well said, sir.

@Porter Stevens – It would be interesting to know what will replace this space.