In 1973, Mayor Harvey Sloan oversaw the creation of Louisville’s first Landmarks Commission, modeled after an ordinance in New York City, making preservation public policy for the first time in the city. Now 39 years later, Louisville has created on average two Individual Landmarks a year, seven Landmarks Districts, a new merged government structure with new political dynamics, and the Metro Council has voted to change how preservation happens in the city.

In early February, Metro Council Member David Yates sponsored an amendment to Louisville’s Landmarks Ordinance, complaining the original system lacked oversight, accountability, and public participation. Quickly joining Yates, eight additional council members, mostly representing suburban districts around the old Urban Service District, signed on as cosponsors. The amendment was introduced in Metro Council on Thursday, February 9, 2012, and over the proceeding six months, politicians and preservationists clashed on how Landmarks designation procedures should work, resulting in a newly politicized process and additional thresholds to be met in the public petition process. But in all the arguing, Louisville missed a real opportunity for preservation reform.

The Landmarks Ordinance Amendment Process

Previously, the process of declaring an Individual Landmark or creating a Landmark District required the following steps, outlined by Charles Cash, former director of of Louisville Metro Planning and Design Services and current board president of Preservation Louisville, in a February email to preservation supporters:

200 signatures of citizens residing in Jefferson County is sufficient to trigger the public discussion regarding the potential Landmark status of an historic district or individual property. The Landmarks Commission process involves site visits, documentation, research, a staff report, committee review and, if warranted, a public hearing before the full Commission. [In the case of a Landmarks District] If a designation results, a Landmark district designation is then referred to Metro Council for final action, whereas, an individual Landmark designation is final when acted upon by the Commission.

Further, for a Landmarks District petition to be filed, at least 200 signatures must come from inside the boundaries of the proposed district (or 50 percent of building owners, whichever is fewer). The Historic Landmarks & Preservation Districts Commission is comprised of 13 unpaid members serving three year terms, ten of whom are appointed by the mayor and approved by Metro Council. To maintain a commission of experts, the ordinance requires that an architect, landscape architect, a historian, an archaeologist, a real estate broker, an attorney, and a member of the chamber of commerce be present on the commission. The remaining three commissioners are held for a member of Metro Council, the Director of of the Department of Inspections, Permits, and Licenses, and the Director of the Metro Louisville Planning Commission. Among the criteria for determining if a structure is a Landmark are whether something important happened there, the architectural or aesthetic quality of the building, its value as part of the city’s heritage, or its contribution to the sense of place in its neighborhood.

This process stood for 39 years, and has been the only recourse for preserving Louisville’s built heritage. It has often been used in last-minute emergency attempts to save threatened buildings, most recently with the contentious fight over developer Todd Blue’s attempt to raze Whiskey Row in Downtown Louisville.

Yates has said his intent in modifying the amendment was to provide for increased neighborhood involvement in the Landmarking process. After much wrangling and several drafts, the final version of the amendment added a requirement that 101 of the 200 required petition signers live or own property within a one-mile radius of the proposed Landmark or within the council district where the it resides, requires notification of residents around the property that it’s being considered for Landmark status, gives Metro Council final say over Landmark designation, and extends the time before a public meeting must be held to 60 days so the Landmarks Commission has time to complete their report on the building, during which time the structure cannot be demolished. Where population density is sparse, the amended ordinance states that ten percent of the residents or property owners within the one-mile radius is sufficient.

“We are in support of historic preservation but too often, residents in the area are not made aware of the effort to preserve a structure or building and what it may mean for the future of their neighborhood,” Yates said in a statement. “This amendment would insure there is input and support for such a designation by the people who live in the area.”

Many believe the Yates amendment was spurred by the 2008 Individual Landmark designation of Colonial Gardens adjacent to Iroquois Park. Developers had proposed tearing down the long-vacant 1902 structure for a strip mall and the neighborhood was divided as to its historic merits. Originally built as Senning’s Park and converted to Colonial Gardens in 1939, the structure has operated as a large beer garden, entertainment hall, and the city’s first zoo with leopards, alligators, deer, and monkeys over the years. (More information on its history and significance can be found in the Landmark report). Despite its Landmark designation, the structure remains on Preservation Louisville’s list of Top 10 Most Endangered Places in Louisville. A Metro Council-funded economic feasibility study is currently ongoing to assist an interested developer in renovating the building.

Two public meetings on the Yates Amendment were held in the Metro Council’s Planning, Zoning, Land Design, and Development committee offering the public an opportunity to testify for or against the changes. On Tuesday, March 13, WFPL reported that nearly 20 people spoke. A second hearing on April 3 included testimony from 52 people, according to LEO‘s Fatlip blog, of which 48 spoke against the amendment:

One common complaint was that the commission has experts in this feild who understand the issue, and council members are not only lacking such knowledge, but might be tempted to side with developer/business interests in order to block a site from being landmarked. Many others also felt that the 1-mile radius on petitions was blocking people from joining the process arbitrarily, as everyone in the city should have a voice. But the overall theme of the dissenters could be summed up in this one-liner that was used: “Let’s remain Possibility City, not Parking Lot City.”

After the hearing, Yates responded to Courier-Journal reporter Dan Klepal’s questions about the overwhelming turnout against his amendment, but Yates was unphased. LEO ran the entire transcript, but here’s a small sample:

Klepal: “It was literally 10 to 1 against it tonight. 4 to 1 last time. What’s the point of open process if you’re not going to listen to them?”

Yates: “Remember Dan, this is an open process per law. I’ve had countless meetings in my office. I’ve talked to people on all sides. I’ve asked for experts to sit down and talk to me. I mean this has been going on for months and months.”

…

Owen: “Well, where are your people?”

Yates: “My people are for it.”

Welch: “They’ve already told us.”

Owen: “But they didn’t show up to speak.”

Yates: “If they’re happy with the way it is, why would you come up to give me ideas about how to change it?”

Owen: “Because this is a community testimony. And the whole community testified!”

The conversation reveals what appears to be Yates’ dissatisfaction that the most vocal preservationists live in a concentrated area, a fact LEO confirmed at least for those who testified. Metro Council member Tom Owen had opposed the amendment and dismissed concerns about where preservationists live, and at one point offered his own compromise amendment. “I’ve been trying to say to my colleagues that the people in the old city with strong views in this have been in the trenches,” Owen told Broken Sidewalk. Preservationists have been wary of such a geographic argument’s validity as well. Preservation Louisville noted the majority of signatures on recent Landmarks petitions are already from people who live closest to the properties in question, citing several examples.

The Peter C. Doerhoefer House, Landmarked in 2011, located at 4422 West Broadway, 40211: Out of a total 363 signatures, 172 of these came from the zip codes 40211 and 40212.

Twig and Leaf, Landmarked in 2011, located at 2122 Bardstown Road, 40204: Out of a total 679 signatures, 245 came from the 40205 zip code – well more than the 200 needed to grant a hearing in front of the Landmarks Commission!

Colonial Gardens, Landmarked in 2008, located at 618 West Kenwood Drive, 40214 showed widespread support for the landmark with 31 zip codes represented and approximately 124 of the signatures came from west of Poplar Level Road.

The petition for the Roscoe Goose House, 3012 S. 3rd Street, 40208…has a total of 350 signatures and 124 of these came from the zip code 40208 and the adjacent zip codes. This petition originated from the support of the South Louisville Neighborhood Council and has engaged the support of several Roscoe Goose descendants.

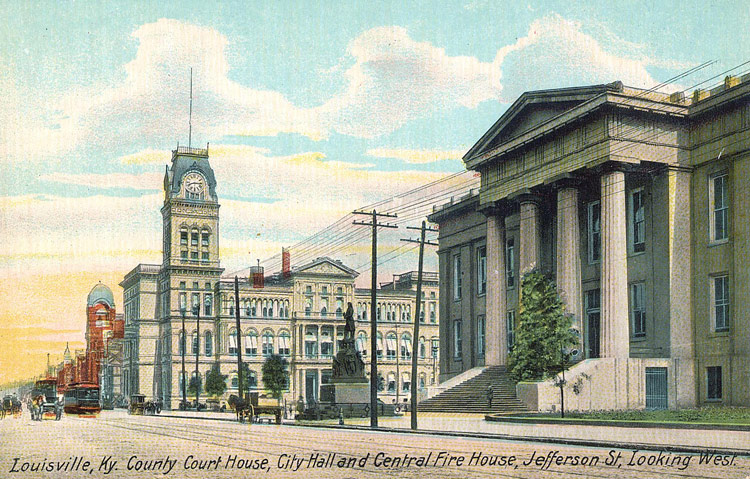

Despite Metro Council’s concerns over the process, there are very few Individual Landmarks being designated in the city. In 2011, for instance, only three Landmarks were designated and two of those were at the request of the property owner (Farmington and the Taylor-Herr House), the third was the Twig & Leaf diner. A fourth proposal, the Kenwood Drive-In Theater, was denied Landmark status. About 20 percent of the Individual Landmarks currently listed are government-owned buildings, such as City Hall, Metro Hall, and the Main Branch Library.

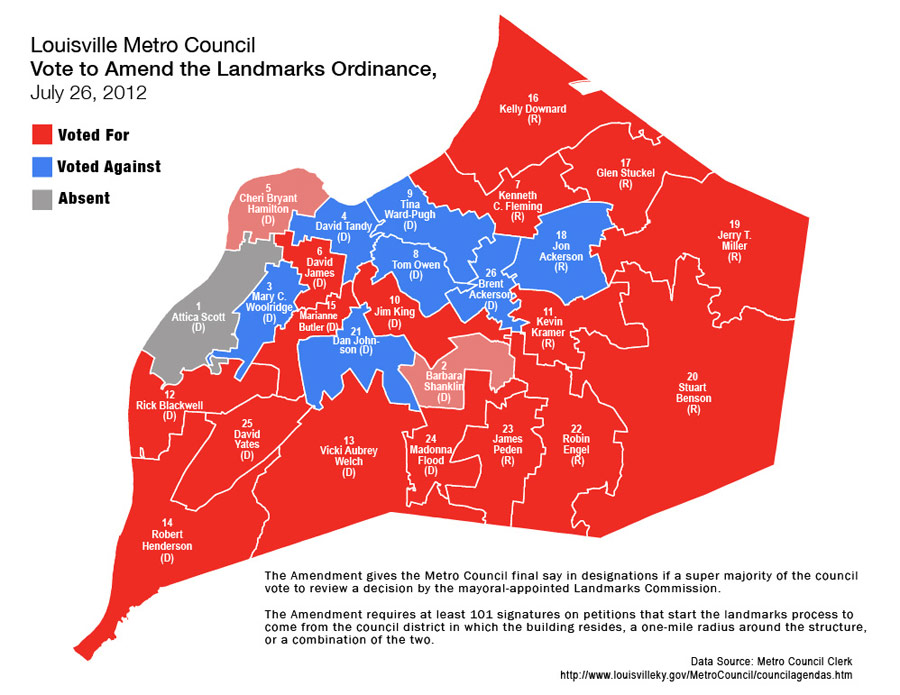

The Yates amendment narrowly passed committee on Tuesday, July 17 with a three to two vote and on Thursday, July 26, and Metro Council voted 16 to 7 in favor of the Yates amendment, with three council members absent. The vote was widely supported in the far-reaching areas of Jefferson County as indicated on the map below by Patrick Smith of MapGrapher. One notable exception being Councilmember David James who represents Old Louisville among other neighborhoods. In a letter to his constituents last week, James remarked, “I am proud to have supported the ordinance because I believe it is important to preserve individual property rights and uniformity in the Metro Government planning process,” adding that the Old Louisville Landmark District “is not impacted in any way.”

Underscoring the divisive nature of the Yates amendment, Mayor Fischer vetoed the amended ordinance on August 2nd, coincidentally on the 50th anniversary of the famous protest in front of New York’s doomed Penn Station, whose demolition helped usher in New York City’s preservation laws and a new awareness of preservation nationwide. The mayor explained his decision in a letter previously posted on Broken Sidewalk. Finally, last Thursday on August 9, Metro Council voted 18 to 7 to overrule the veto, making the Yates amendment law six months after it was originally proposed and marking the first time a mayor’s veto has been overruled since the merged city-county government was established.

That evening, Marianne Zickhur, director of Preservation Louisville, said,” The fact of the matter is its a loss for preservation. It’s unnecessary to politicize the process as the experts know how to use the criteria in front of them.” Architect Steve Wiser agreed, “The enforcement aspect [of the Landmarks Ordinance] has been weekened by this process,” he said. “I see more deteriorating buildings and I only see that getting worse.” Wiser said after great turnouts by the preservation community at previous meetings, the final Metro Council meeting was poorly attended, with only five preservation supporters present. While disappointed with the outcome, Zickhur was ready to look ahead, “People that support preservation will continue to fight for preservation.”

Problems with Preservation Still Exist

Following along with the Yates amendment process and the rhetoric thrown around by Metro Council politicians, you might think that preservationists are among the most dangerous groups in town, threatening developers, the community, and all property owners with their willy-nilly attempts to control property rights and adversely affect home values by forcing people to save eyesores across the city. This (only-mildly-exaggerated) assumption couldn’t be further from the truth. Louisville’s preservationists have been fighting an uphill battle since before the city’s Landmark Ordinance hit the books in 1973, and while those challenges continue, the hard work of those dedicated to Louisville’s heritage have made a positive impact. Tom Owen pointed to the Parkland Landmark District as one clear success story, “Central Parkland would have been dead long ago” without protected status. But still, preservationists are too-often derided as meddling do-gooders in Louisville.

On nearly every preservation battle, you’re bound to hear someone throw out the line, “If you want that building preserved, why don’t you go and buy it!” In many cases, this is already exactly what happens, such as a wealthy group of investors swooping in to save Whiskey Row, or another group led by Gill Holland buying the old Wayside site in Nulu. Louisville can’t continue to expect that preservation-by-patron will be a realistic or sustainable way to preserve the city’s built heritage forever.

Even before the Yates amendment, preservation in Louisville was structured to be difficult. Today, the financial bar for wrecking the city is significantly lower than that of attempting to save it. In order to file the petition that kickstarts (but doesn’t guarantee) the Landmarks process, a $500 fee must be paid, which can add up when multiple buildings are in play like at Whiskey Row. On the other hand, the two most common wrecking permits, depending on a building’s size, begin at $50 to $75 for the first 1,000 square feet with an additional $10 for every 1,000 square feet thereafter.

Today we’re dealing with a different set of preservation problems than we were in decades past as people are returning to the core city, mid-century modern architecture is becoming historic, and we continue to struggle with vernacular preservation of the city’s urban fabric. Significant challenges in preserving Louisville’s heritage remain. It’s telling, for instance, when six of Preservation Louisville’s Top 10 Most Endangered Places are broad typologies like “shotgun houses” or “corner stores” instead of individual structures. The city’s core urban fabric is threatened and the current process is ill-equipped to deal with the challenges that lay ahead as we continue to grapple with issues of vacant and abandoned property and the aftermath of the foreclosure crisis. It hasn’t been enough in the past to show that preservation promotes the economic well-being of communities, is more eco-friendly than building new, creates more jobs than building new, and creates a distinctive character of place that promotes psychological well-being.

Looking around Louisville it should be obvious what a boon preservation has been for building strong local businesses. When you think of your favorite local businesses, chances are they’re located in an old, renovated structure, perhaps even in a Landmarks District. Besides having the quirky character that keeps Louisville weird, the financial ease of renovating these already-existing structures as opposed to building new serves as a sort of economic incubator for the city’s entrepreneurs. A quick survey of Nulu, for instance, shows that nearly all of the new businesses have opened up in old buildings. But with the stock of easily-rehabbed structures dwindling in Nulu and across the city, preservation should be seen as directly linked to the economic well-being of our local economy. The more historic buildings we have, the more local business can occupy them.

A Comprehensive Preservation Fix

Instead, it’s time Louisville reconsider preservation altogether, not just the Landmarks Ordinance, and develop a comprehensive demolition and rehabilitation policy for the city. Lexington recently held a symposium on historic preservation, calling experts from around the country together to discuss the profession. Tom Eblen has a great write-up of what was discussed including a need for engaging disenfranchised communities not typically included in the discussion that are wary of preservation as a gentrifying force meant to displace existing residents, a decreased emphasis on “saving the homes of the rich and famous,” and even potentially changing the name of historic preservation altogether.

It was difficult enough to move through the Landmarks process, and now the Yates amendment has made it a little bit more so, but there are bigger issues that must be addressed. If the Metro Council members who voted for the Yates amendment were so concerned with public notification and review of a process that inherently is not destructive to the community (quite the opposite, countless studies show that preservation raises economic values of surrounding properties), they surely would be interested in increasing the transparency and review capability of the actual destruction of the city. Wrecking a property will clearly have just as much if not more impact on surrounding properties and neighborhoods as preserving one. Demolition review is already a common practice around the country, so let’s take a look at how it works.

Cities have a variety of codes and regulations that govern how land and buildings are used. Zoning codes, for instance, can prohibit certain uses from certain areas. If someone wants to build a toxic dump in a residential neighborhood, the “If you didn’t want a toxic dump on this property, you should have bought it” line seems pretty silly. The spectrum ranges from building and fire codes that provide for basic public safety to zoning, overlay, and preservation rules that govern how communities are built, look, and feel. Individual buildings and properties in cities don’t exist in vacuums and can externally affect the surrounding community, for good and bad. Some buildings might be worth preserving, but can’t muster support to be declared a Landmark (or rightly shouldn’t be elevated to Landmark status). Other cities have dealt with this issue by implementing a demolition review process that can provide transparency and some protection for historic buildings under threat.

Under St. Louis’ demolition review policy, if a building is listed or is eligible for listing on the National Register or sits in a National Register District, any demolition permit requested is put on hold for 45 days and the demolition permit applicant is required to photographically document the structure in question. During that time, the city’s Cultural Resources Office or Preservation Board can review the permit application and issue a written opinion to the Building Commissioner. The Preservation Board holds a public hearing and a panel of non-political experts decides to approve or deny the permit based upon preset criteria such as the condition of the building, the proposed redevelopment plans and urban design, the architectural quality of the structure, its potential for reuse, or the effect on the surrounding neighborhood. These hearings can be contentious, and it’s no guarantee that a historic building will be preserved. Like Louisville’s Landmarks Commission, St. Louis’ Preservation Board is a panel of experts, not a group of preservation zealots. This review opens up the demolition process to be more inclusive and transparent. If a permit is denied, there’s also an appeal process built into the system.

Right now, each Ward (like a Metro Council district) in St. Louis can opt in to the review program, and most do, but a recent demolition of an old theater in an area without review has sparked anger and calls for city-wide preservation review.

Sometimes what results in these cases is the Board will choose to deny the demolition permit until the time that a building permit is issued. That could avoid cases like what happened at the D&W Silks building across from Slugger Field that was demolished for a parking lot that is supposed to give way at some time to an office tower. With better preservation options, Metro Louisville could have conditionally approved the demolition of the structure once the developer was ready to build on the property. A demolition review process also helps cities prevent more surface level parking lots from being built downtown.

Could this type of demolition review work in Louisville? Absolutely. In fact, the Landmarks Commission has recommended and requested such a program for at least the last six years (the only annual reports available online). It’s time Louisville brings its preservation policy into the 21st century and joins the ranks of cities like St. Louis to preserve its built heritage. Until Louisville gets serious about preserving its history and building stronger, more sustainable communities, buildings like this townhouse and more significant buildings all across the city can be torn down without oversight and with impunity.

[Note: These before and after views from St. Louis are unrelated to this call for demolition review, but demonstrate what can happen when a city is not so trigger-happy with the wrecking ball. In Louisville, all three of these examples likely would have been torn down and never considered for rehabilitation and anyone suggesting otherwise likely scoffed at. More info on these projects here and here and here.]

Despite having submitted the application, required petition signatures and a check for $500 over a year ago, the first designation review that will include the new amendment regulations will be for the Hogan’s Fountain “TeePee” Pavilion in Cherokee Park. It’s designation is supported by a number of preservation organizations, neighborhood association groups, and thousands of Louisville citizens. It is opposed by Metro Parks. Not sure how Metro Council can keep the politics out of this contested designation of a city-owned property…despite the objective criteria for historic designation…but we’re anxious to see.

I want to fight back, but I’m not sure how. Do you know where I could get involved?

After reading the discussion of the South Preston Demolition Permit and this post, I have just a few questions:

So in places like St. Louis the established built environment and potential for re-use is the development allowed by right? Retaining that fabric, that un-replicatable aesthetic, is part of the local value-system? The elected officials codified that which the local community believed to be important, motivated by coffee-shop conversation, pride of place, fear, or familiarity of the economies of preservation, or any other reason – at least one of which was a rational, greater-good argument that lead to the creation of the ordinance? A leveled site is less valuable than an old home or warehouse, to the local community?

Through this ordinance Demolition, then, is allowed as a condition – like a junk yard or a day care use? Demolition has a place, but it is assessed by a body we trust to reflect our local community values? We trust that body because they are experts? They are experts in what?

Demolition could be as valuable to the community as a day care – but the day care use could fit inside many of the existing buildings? Demolition could be as necessary for the local community, or as detrimental to the surrounding neighborhood – as a junk yard use? The worth of the structure is evaluated independently of the worth of the potential (re-) use of the building; the promise of an office use, for example, has no affect on the evaluation of the demolition permit?

The burden to document the structure shifts to the one who wishes to alter it significantly? They must document x, y, and z reasons why their design for the property is superior to that of the existing structure. Until the property owner, or developer, has the development plan approved through the regular process, no demolition permit will be allowed? To assure that the building remains in place, no demolition permit is allowed until the building permit for the superior structure is approved? Must the applicant produce proof that they have secured a funding source before the demolition permit is approved, or is that assumed with the application for the building permit?

How would this ordinance address structural integrity or apathy towards decay?

This ordinance does not apply uniformly to the entirety of the local jurisdiction, so areas outside of the protected area could adopt their own demolition criterion that reflects the values of those in the district, or continue as business-as-usual? The neighborhood, the district, and the city could still change considerably – as a city should with time – but it does so with some respect to what is lost will never be restored, whether that is on a case-by-case basis, good or bad?

This is totally random, but I am pretty sure I have an old news clipping of my great aunt Mickey on the front advertising for them. Can you verify it for me? I have a photo. I know it’s here. I just want to know if this IS the place she was at. Thanks!

Natalie