“Could you be mine? Would you be mine? Won’t you be my neighbor?” -Mr. Rogers

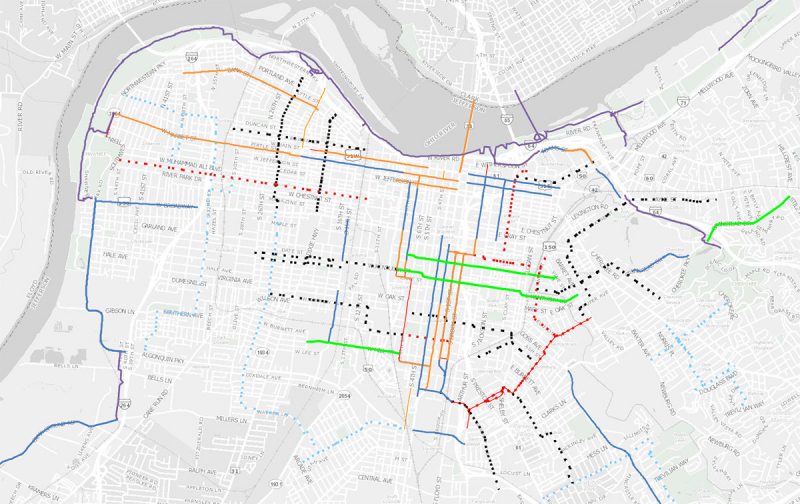

Consider a map of Louisville with the major streets and expressways highlighted. It looks a lot like a bicycle wheel: the Watterson and Snyder expressways form concentric circles around the city, and arterial roads (like Bardstown Road or Dixie Highway) and Interstate 65 form spokes that bring traffic between downtown and the expressways. It looks like a pretty efficient system viewed from high up in the sky, and reflects Louisville’s early growth around country turnpikes and streetcar lines radiating from the urban core. However, with this picture in mind, it’s ironic that bicyclists are not permitted, or prefer not to use, most of these streets. They are high speed, busy roads, with low air quality and high levels of noise pollution, which are less than ideal if one is looking for a leisurely, enjoyable, quiet bicycle ride or a stroll around the neighborhood.

Louisville, like a lot of cities, has many options besides expressways and arterials, including secondary connector streets, low-traffic alleys, and quieter neighborhood streets which can provide a lower-stress transportation experience. If you can connect these secondary-street routes and provide innovative infrastructure improvements to calm traffic further, a new network of bike routes can take shape, a concept typically called a “bike boulevard” in many cities. Louisville is currently implementing such a system, what the city’s bike department, Bike Louisville, is calling “Neighborways.” The city hopes these new bike boulevards will encourage and enable bicyclists and pedestrians to take advantage of alternate-route options for moving safely around the city—and eventually lead to an uptick in biking overall.

Rolf Eisinger, bicycle and pedestrian coordinator at Bike Louisville, told Broken Sidewalk that the idea for Neighborways came as a response to many citizens expressing concerns about motor vehicles dangerously speeding through their neighborhoods creating dangerous conditions. A study in the United Kingdom, for instance, showed that the chance of death increases significantly at higher speeds: at 20 miles per hour, there is a 5 percent chance that a person struck by a motor vehicle will be killed, while a 40 mph, the chance of death is 85 percent. Some cities like New York City have even reduced the city-wide default speed limit to 25 miles per hour to promote pedestrian and cyclist safety.

The Neighborways idea is to slow down traffic on neighborhood streets, creating a safer and quieter environment for all users of the neighborhood: kids who are playing in the front yard, residents who want to walk down to a nearby park, or cyclists moving through the city. According to the Bike Louisville website, “Louisville’s Neighborways will be optimized with streetscape design features such as street trees, green infrastructure, and other forms of design to reinforce slower speeds and a positive rider experience.”

Bike Louisville is finishing the first phase of its Neighborways plan, which consists of painting “sharrow” markings on many neighborhood streets to guide cyclists to use those streets and remind motorists to share the road with cyclists. And already, sharrows are starting to show up all around town. When complete, there will be 100 miles of Neighborways marked with sharrows throughout the city.

Phase II was recently approved by Metro Council, and will begin soon with a focus on creating wayfinding signage so system users can find their way through the network and connect to important “nodes” or destinations along the way. This signage could take the form of signs like the ones above that indicate a destination and the distance to bike there.

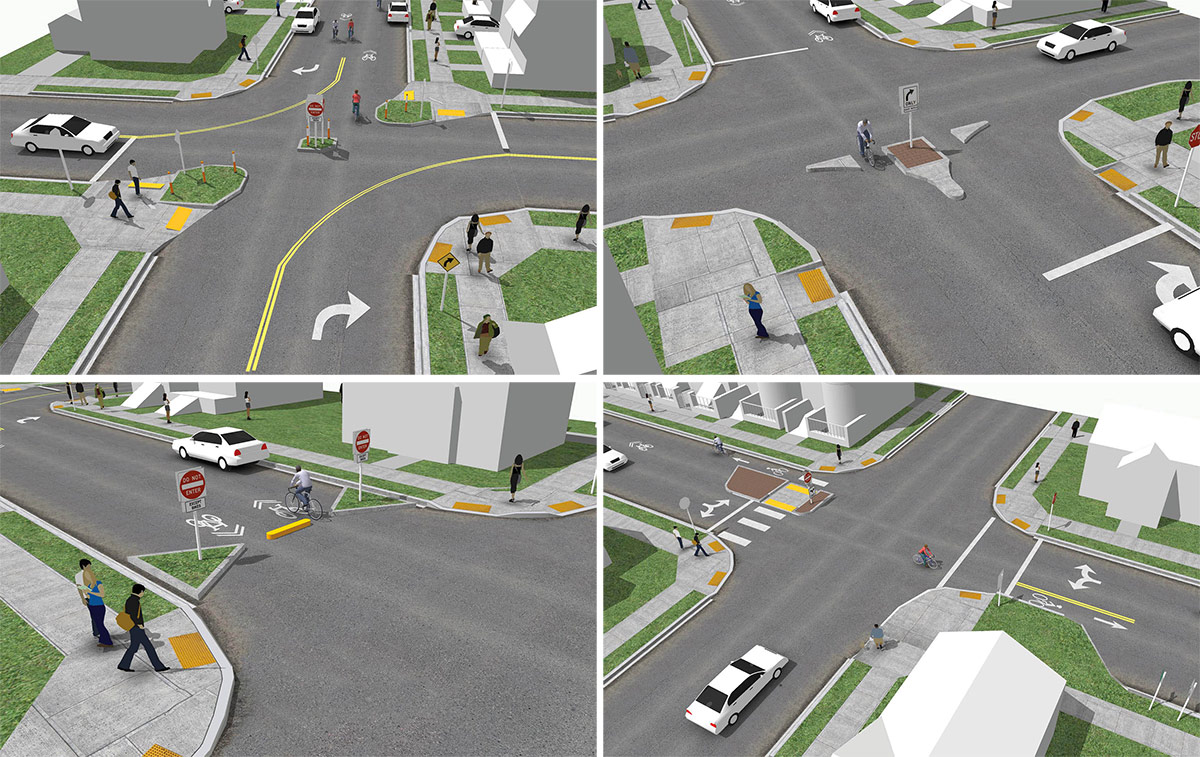

Eisinger elaborated that there is also a plan to build “bump outs” on some streets—either intersection “neckdowns” or mid-block “chicanes”—to create a serpentine path of travel that forces motorists to reduce their speed. According to Bike Louisville, “As funds become available, routes show increased use, and local neighborhood support builds, the Neighborways could evolve to incorporate higher design details such as signage, traffic calming, and traffic reduction.” More ambitious future phases could also combine these traffic calming measures with green infrastructure that adds landscaping along the routes while diverting stormwater from Louisville’s combined sewer system.

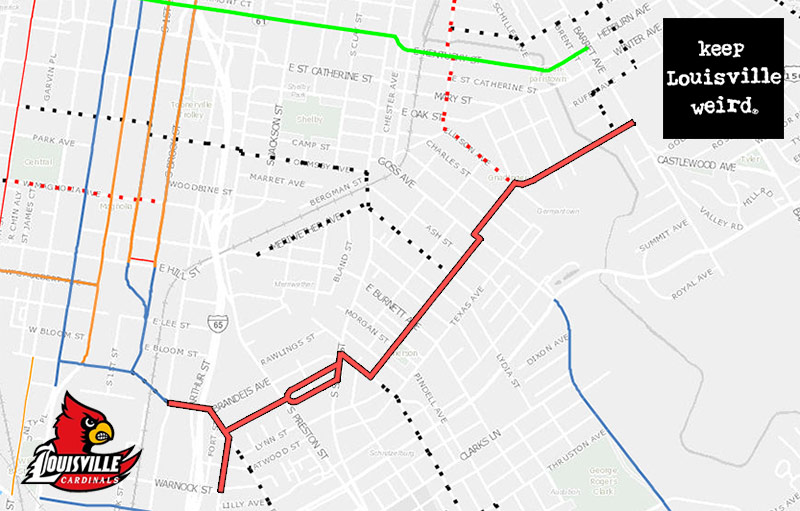

One of Louisville’s first Neighborways to come online is a route that connects the University of Louisville with the Highlands by avoiding busy Eastern Parkway. The route, demarcated along the way by sharrows, leads cyclists through the shifting neighborhood grids of St. Joseph, Schnitzelburg, and German-Paristowne, following secondary streets that allow cyclists to relax and enjoy the ride. Dotted lines in the map aboce indicate future routes currently under development.

Louisville is joining cities such as Tucson, Portland, Ore., Berkeley, and Minneapolis, which have already implemented significant Neighborways-style networks. Portland has an extensive, well-developed system of what they call Neighborhood Greenways. I had the chance to see Portland’s bike boulevard system first hand recently and it’s clear that the city’s system is heavily used by cyclists and pedestrians. They use sharrow markings, wayfinding signage to show distances and directions to nearby attractions, and make extensive use of traffic diversions, which in many cases restrict motor vehicle traffic by creating “dead ends” that cyclists and pedestrians can avoid.

Traffic diversions are intended to keep motor vehicle traffic light on bike boulevard streets so cyclists feel more comfortable using the designated routes. At many intersections, motor vehicles are forced to make a right turn off a neighborhood street, but pedestrians and bicyclists are permitted to go forward in any direction. Sometimes this takes the form of a “contraflow” bike lane where a two-way street becomes one-way for motor vehicles and remains two-way for bikes. This limits the volume and speed of motor vehicles on these streets, creating a very welcoming environment for people choosing alternate modes of transportation.

Currently, Louisville’s Neighborways plan does not include any of the above types of traffic diversions commonly seen in other cities. Interestingly, though, Louisville has many streets which have been blocked off to motor vehicles through traffic diversions simply to prevent “cut-through” traffic. One of the most well-known examples is at Garvin Place and Oak Street in Old Louisville (above), known as “Garvin Gate.” A simple modification to this design to allow cyclists through without riding on the sidewalk could create a bike boulevard–style traffic diverter connecting to the Oak Street commercial corridor. These types of intersections provide already-existing infrastructure for traffic calming which benefits pedestrians, bicyclists, and residents of those neighborhoods.

This program is not without controversy. One problem is that the NACTO guide has about as much relevance to good engineering as the National Board of Ophthalmology does to being a board-certified eye doctor.

The Shared-Lane Marking, also called a “sharrow,” is listed in the Manual of Uniform Traffic Control Devices–the definitive engineering manual (which, sadly, also has some foibles in how the sharrows are to be placed). The MUTCD specifically states that the sharrow is NOT a way-finding marker. Using it as such violates the Uniform Vehicle Code.

Many of the much-vaunted bike lanes create more crossing movement conflicts than they resolve. The only reliable things about bike lanes as they are being produced in Louisville are that they will generally be on the worst pavement in a several block radius, and that they will not be swept of debris moved into them from passing motorized traffic regularly. Several openly violate MUTCD guidelines (placement to the right of a right-turn-only lane, as is found at the south end of Brook Street at Cardinal Boulevard, or striped to the intersection where motorists are likely to make right turns from a lane to the left of a bike lane). Several have cyclist traps in them (below-grade storm grates, gaps between those grates and their frames, as can be found on Grinstead Drive). Several are such that a cyclist in the bike lane is subject to “dooring” crashes (most of the ones in the downtown grid).

I’m told that “Louisville doesn’t have a dooring problem,” but the proliferation of door-zone bike lanes and the refusal to remove existing ones suggests that Louisville WANTS to have a dooring problem.

I’m a fan of the wayfinding signs presented and excited by the ‘dotted lines’ on the maps representing paths under development. Without getting too down in the weeds over regulations and standards, sharrows to me have always been…’meh’. As a stopgap to something greater if/when ridership improves or a sincere placeholder until more funding comes along, they’re fine. But I think they are often used as a cop-out to things such as Phase II and beyond, listed above. I do agree with Tom above that sharrows shouldn’t be used as replacement for wayfinding signs. I also think sharrows shouldn’t be used in place of greater commitment.

I think the engineered traffic calming devices really are necessary to substantially increasing ridership and a neighborhood’s positive perception of cycling. Unfortunately, tying these things to funding availability, route usage, and neighborhood support sounds a bit disingenuous and insisting on the chicken’s presence before the egg. Though that probably is reality.

Anyway, existing Louisville cyclists mostly know their way around. And they are not rapidly increasing in numbers enough to support much of this on their own. But I can see how a good route system could leverage some low-hanging fruit (young professionals moving into town…Highlands, Germantown) into ridership gains. I know if I were transplanted into Louisville, a good, signed pathway system would obviously help me navigate but also serve as a marker of Louisville’s bike friendliness.