Last week, we reported that the conversion of the old J.F. Kurfees Building on the corner of Brook Street and East Market Street into a mini-storage facility had begun. Many readers expressed dismay at the project citing the mini-storage use as not befitting such a significant building in Downtown trying to reinvent itself as a dynamic place.

While mini-storage is not a particularly exciting use, I find it hard to fault the developer, Atlanta-based NitNeil in partnership with Louisville’s Aaron Willis, for their project. It’s important to remember that this building had been vacant, on the market, and without a buyer since 2010. That was plenty of time for someone to step up to the plate to take on a more exciting project. No one did.

And now there’s a nearly $2 million investment that will—at the very least—mothball the building until a future, better use comes along. And it’s inevitable that one will. History tells us so.

Take for instance the case of the Haldeman Warehouse, which saved and then nearly destroyed one of Louisville’s finest landmarks, the old Customs House & Post Office on the corner of Third Street and Liberty Street a few blocks away.

Built in 1858, today’s Landmark Building was described by the Louisville Journal at the time as “one of the most massive buildings we have ever seen”—the surrounding area would have been predominantly houses at the time. By that measure, there’s a comparison to be made about such a large and out-of-scale intrusion into the city by an out-of-town developer (the federal government) and new projects going on today.

The Italianate structure features three-foot-thick walls, and, according to the Encyclopedia of Louisville, was among the first buildings in the city to feature Indiana limestone, giving it a gleaming monumentality in a city of wood and brick.

Designed by architect Elias E. Williams, the building is his only remaining example today—he also designed the now-demolished 1857 Masonic Temple at Fourth and Jefferson, worked on the city’s Marine Hospital, and built many homes throughout the city. (Some research indicates that Williams may have executed a design by east coast architect Ammi Burnham Young, but that cannot be verified.) The structure also boasted indoor running water and restrooms—two years before the Louisville Water Company was established half a block down Third Street.

The structure almost didn’t happen at all, it turns out. In contentious federal budget hearings in the 1850s, funds for the project were derided as misappropriation of funds and not needed in “a city in the backwoods of the West,” according to an 1853 report in the Louisville Daily Courier. That year, however, federal funding for the project approached $180,000—no doubt in part to U.S. Secretary of Treasury James Guthrie, a fellow Kentuckian, who was in office at the time.

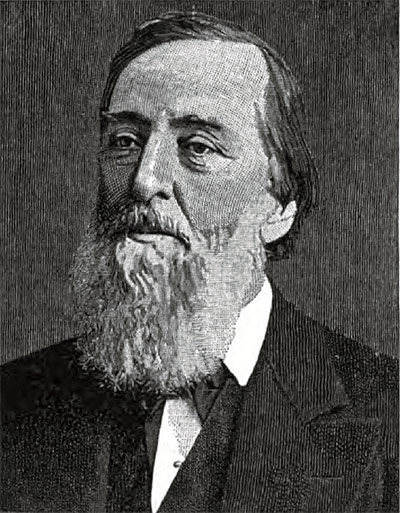

The building opened in 1858, but as the city and business within its bounds rapidly grew, the federal use had outgrown the building and planned for an even grander Customs House at Fourth Street and Chestnut Street that opened in 1892. (We already know what happened to that structure.) The old customs house then sat vacant for four years until Walter N. Haldeman, publisher of the Courier-Journal, bought the building at auction for $50,000.

(An interesting aside: In 1854, as publisher of the Louisville Courier and an outspoken supporter of slavery and the South, Haldeman’s house was confiscated by Union troops and the Courier‘s offices seized. Printing was moved beyond the reach of the Union forces to Bowling Green and Nashville for a time. Later, he was one of the founders of Naples, Florida, and owned Louisville’s Major League baseball team, the Grays.)

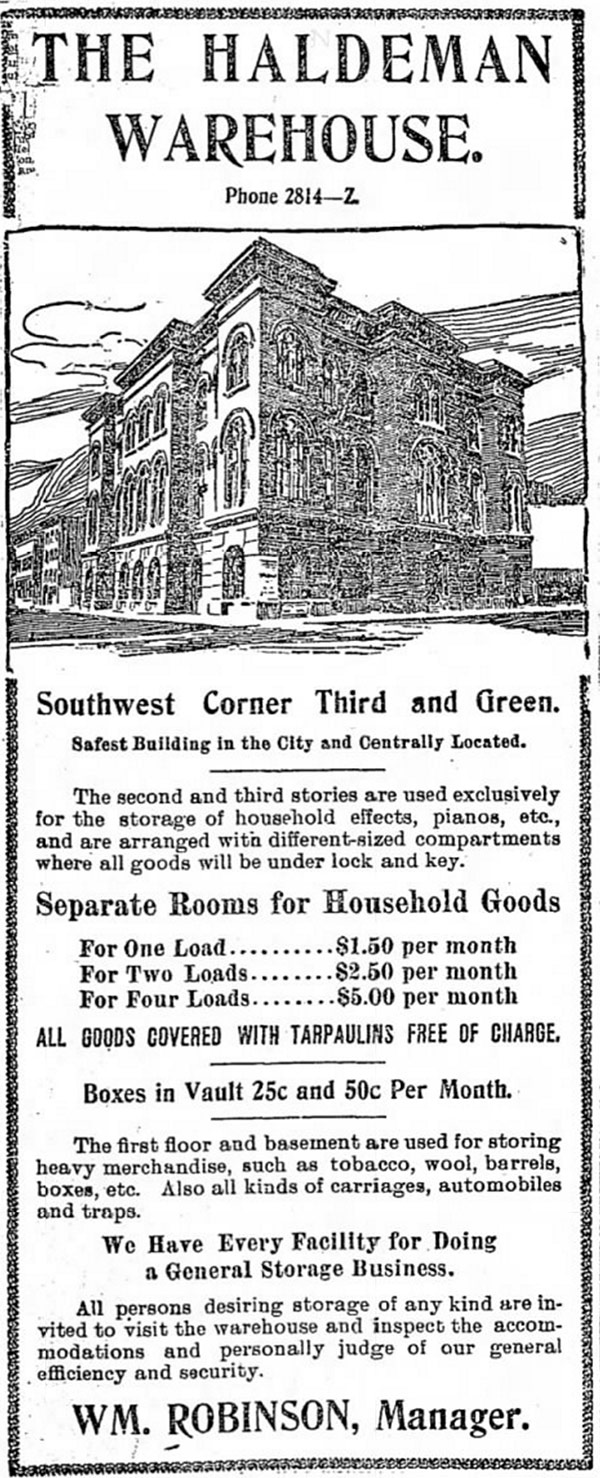

Haldeman had initially planned to move his newspaper’s offices to the building, but then changed his mind and opted for mini-storage. He announced the completed warehouse in October of 1899 with prominent ads in his newspapers.

“The former Customhouse building on the corner of Third and Green streets has been repaired and thoroughly cleaned, and will be known hereafter as the ‘Haldeman Warehouse’,” one ad declared. “It is centrally located and is virtually fireproof… The building, which is very large and known as the strongest and safest in the city, is now ready and open for business.”

The first floor, which was once the proud post office, now housed tobacco, wool, barrels, boxes, carriages, and buggies, according to advertisements. Above, the second and third floors were reserved for “household effects” such as pianos. The basement, used to store bourbon in bond under its federal use, now housed private stocks of wine and brandy alongside stores of apples and potatoes. Additionally, “There are ten large and secure vaults, with the best combination locks, where silverware and valuables will be securely stored,” the ad continued.

Haldeman died suddenly at the age of 81 in May, 1902, soon after being struck by a trolley car. According to his obituary in the New York Times, “He was a man of unusual force of character, but remarkably modest, so that he resented any form of publicity about himself.”

The building continued on as mini-storage for another eight years, when Haldeman’s son, Bruce, announced plans in 1907 to raze the building. According to the Encyclopedia of Louisville, the structure exists today almost as a fluke: the cost of demolishing such a sturdy building—with its three-foot-thick walls—proved too expensive.

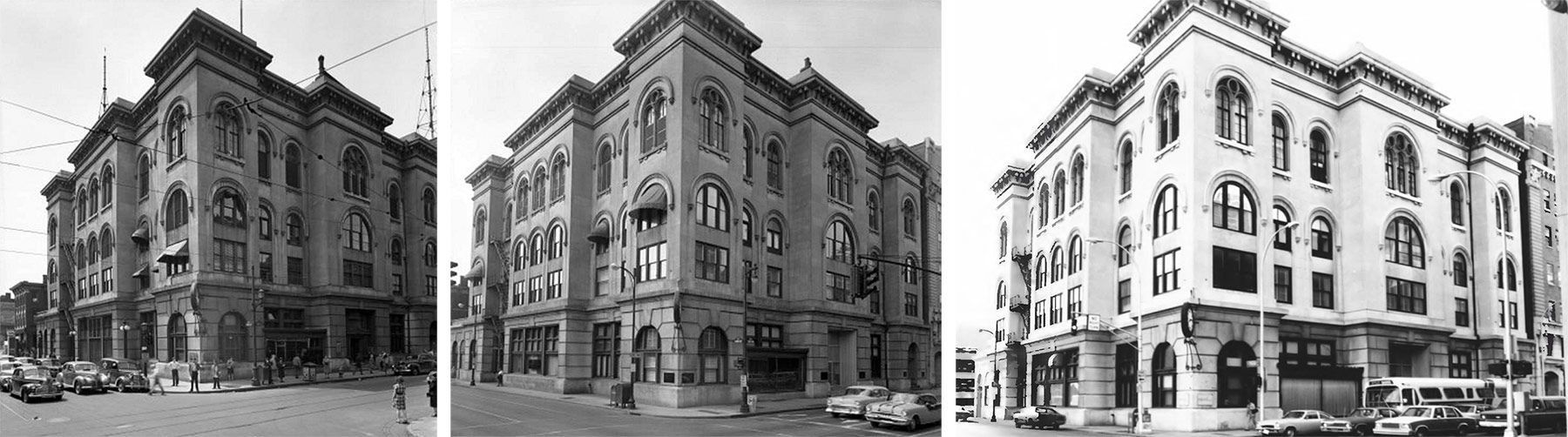

Instead, the younger Haldeman opted to continue the mini-storage business in a new concrete addition next door and, in 1911–1912, asked architect John Bacon Hutchings to remodel the old customs house into offices for the Courier-Journal. During that renovation, the tall second level—once home to a grand federal courtroom—was divided into two floors. You can see the modification today with a simple stone divider between different window systems on the second and third floors. The fourth-floor (or the original third floor) shows how the original window layouts appeared.

Back in 1907, the new warehouse building—still standing today—got underway. “Plans have been drawn for the construction of a new building adjoining the Haldeman warehouse at Third and Green streets,” according to a 1907 edition of the Bulletin of the American Warehousemen’s Association. “The building will be erected on the vacant lot just west of the warehouse and will be built of concrete. The estimated cost is $40,000.”

[beforeafter]

[/beforeafter]

[/beforeafter]

[Above: The original structure’s design seen in 1946 and the building in 1959 after a later modification. Courtesy UL Archives – Reference, Reference.]

The structure by architect Arthur Loomis was clad in brick with limestone in an Americanized version of Beaux Arts featuring prominent eagle details. The original building had few windows, like most warehouses of the time. A later renovation to make additional room for the C-J offices punched the windows we see today into the facade with a slightly reconfigured look.

Loomis was a prominent architect in Louisville, also designing the Levy Bros. Building at Third and Market streets, the now-razed Todd Building at Fourth and Market, and the Speed Building at Fourth and Guthrie.

Much was made of the new structure’s modern use of concrete, which was just taking off as a building material. “Work on Louisville’s new sewerage system is to be started within a short time and it has been given out by the commissioners that the sewers are to be constructed of reinforced concrete,” said an August 16, 1907 account in Rock Products. “Concrete sidewalks are becoming the popular thing in this city and are rapidly replacing brick.”

In the late summer of 1907, a strike threatened to shut down construction in the city. “The prospects at the opening of the season were very flattering and had it not been for this unnatural delay there would have been more concrete work begun here than was ever known in the history of the city,” declared that same Rock Products report. “In so far as the concrete industry is concerned locally the strike among the building trades has had a rather serious effect on conditions and the operators are all complaining about its demoralizing effect.” Haldeman’s new warehouse was fortunate, and the National Concrete Construction Company was awarded the large commission later that year. (It later changed names to the Fireproof Storage Company Warehouse.)

After being vacant for four years, subsequently converted to mini-storage for 12 years, and barely escaping demolition, the old customs house was back in the game. The structure has remained office use since its conversion, although it has changed names several times along the way.

In 1922, WHAS radio—the city’s first station—began broadcasting from the building, according to the Encyclopedia of Louisville. In 1925, that station broadcast the first live running of the Kentucky Derby. The Courier-Journal and the Louisville Times called the building home until 1948 when the company moved to its new Art Deco headquarters at Sixth Street and Broadway.

The building was remodeled again in 1950 for general office space and was named for one of its tenants, the Louisville Chamber of Commerce. In 1963, it became home to the Old South Life Insurance Company, and again in 1979, it was sold to Louisville developers James and Kay Morrissey who spent $2 million on renovations. The customs house structure was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1977 and the adjoining warehouse was added in 1980. In 1996, Legacy Properties purchased the building, adding its modern name, the Landmark Building. In 1999, it changed hands again, this time to Whittington Realty Partners. Then in 2006, its current owners, the Liberty Landmark Group, took over.

In three years, the old customs house will celebrate its 160th anniversary. That’s more than most buildings in Louisville can boast. That year, the area around Third and Liberty will appear very different, most notably with the completion of the Omni Hotel & Residences across Third.

But the building was also used for mini-storage for over a decade. And that very well may have saved its life. While the mini-storage use going in at the Kurfees building today might not be ideal in such an adaptable and beautiful historic structure, we hope the interim use will lead to much better days ahead.

[Top image: The old U.S. Customs House & Post Office as it appeared from Third Street circa 1956–1966. Courtesy UL Archives – Reference.]

Branden, great article. I do agree with readers and absolutely I would have preferred a more significant use such as apartments, hotel or distillery. We tried, however, the hurdles to overcome were too great. People are very quick to judge developers and most simply do not understand all the obstacles. Bottom line, I saw a deteriorating building and it’s historic details will be preserved with an appropriate use today. We aren’t dismanteling it for storage or simply leaving the facade. It will be restored in its entirety. I have always maintained that the future may look different for this building. The work we’re doing today sends Kurfee’s down that path.

Hopefully the next project will be one that everyone enjoys!

Great article – well researched, well written, and it makes me even more glad to call Louisville home. Good luck with the project, Mr. Willis.