On December 11th, city and state officials—Mayor Greg Fischer and Governor Steve Beshear among them—lined up to praise Louisville’s latest economic development project: a plan for a new six story structure to expand Kindred Healthcare’s space at the site of today’s Theater Square. The plan calls for demolishing the 1980s-era Theater Square to build the mixed-use office building, bringing in 500 jobs to Downtown Louisville—and the city leaders couldn’t be more thrilled as was evidenced by Mayor Fischer’s terming the project “a dream come true.”

Now that a few months have passed since the announcement, we’ve had a chance to step back from all the pageantry of a public unveiling and it’s time to take a closer look at how the proposed development will actually help—or in some cases hurt—Downtown Louisville.

While it’s undeniable that adding 500 well-paying jobs to the city’s core is a positive move, the physical manifestation of that addition leaves a great deal to be desired. And it’s not entirely the fault of this proposed new building—it’s a sequence of actions over the past 30 years that have eroded the urban fabric of Louisville’s once-most-prominent intersection, leaving scars for blocks around. What this building doesn’t do, however, is attempt to address any of the site’s existing shortcomings, and, more troubling, will cement these errors for another generation.

This week, the city’s Downtown Development Review Overlay (DDRO) Committee will discuss the project at its regular meeting on Wednesday, March 11 at 8:30a.m. in the Old Jail Building Auditorium (514 W Liberty Street). Leading up to that meeting, let’s take a look at where we’ve been, where we are, and where we’re going.

Details of the Current Scheme

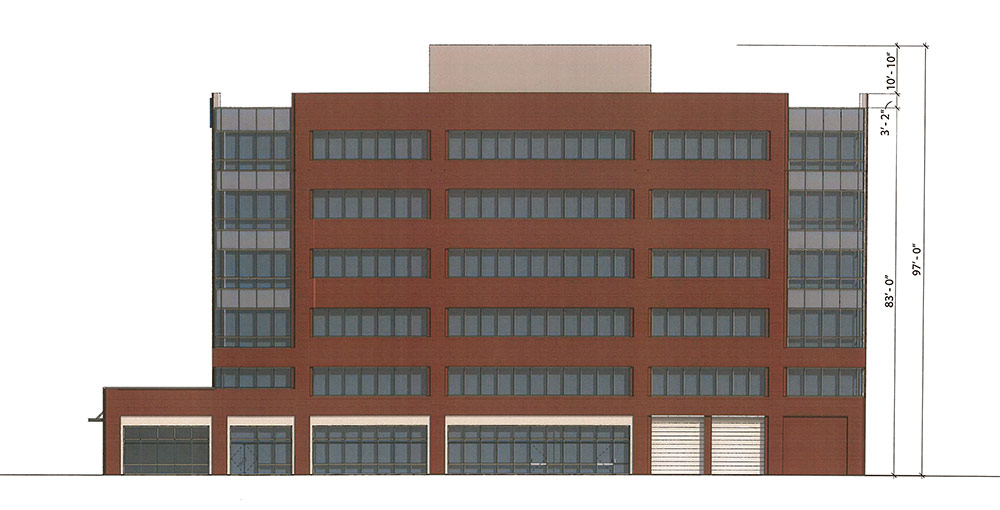

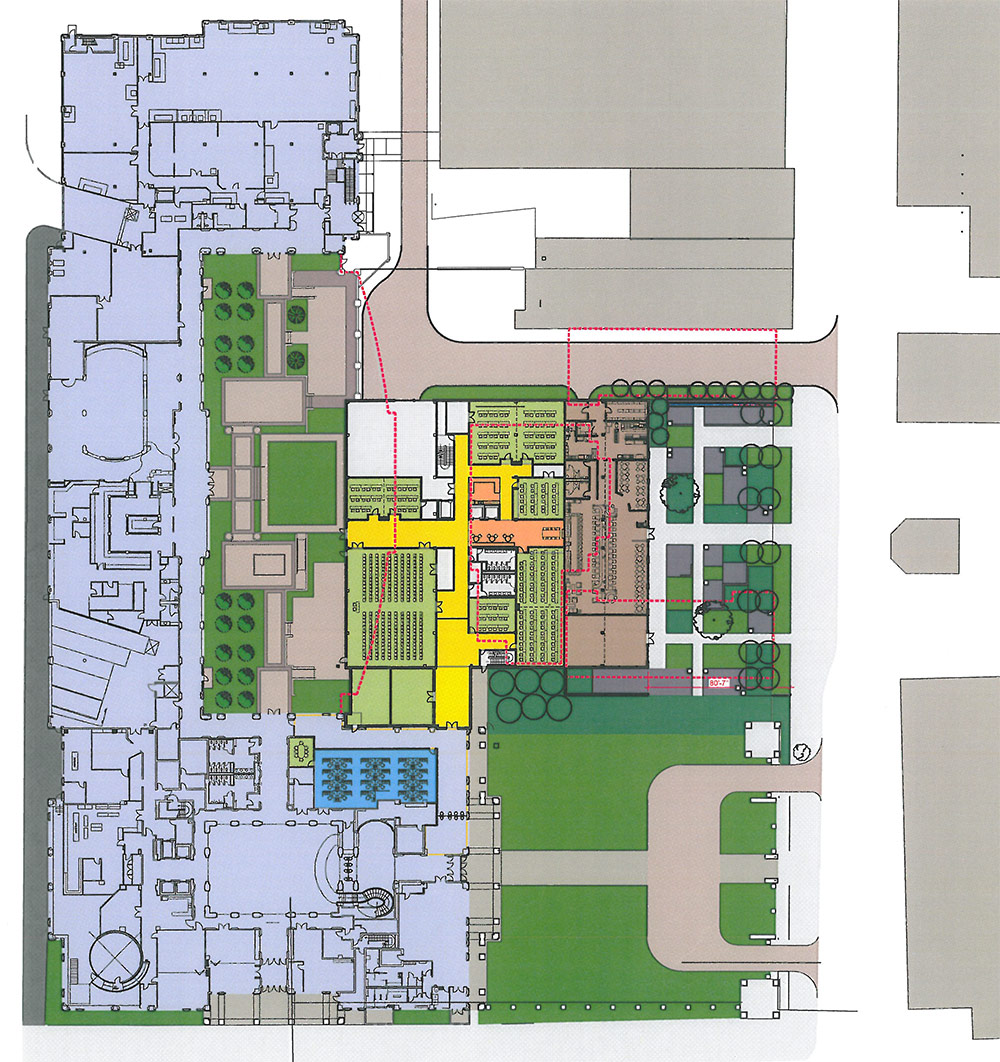

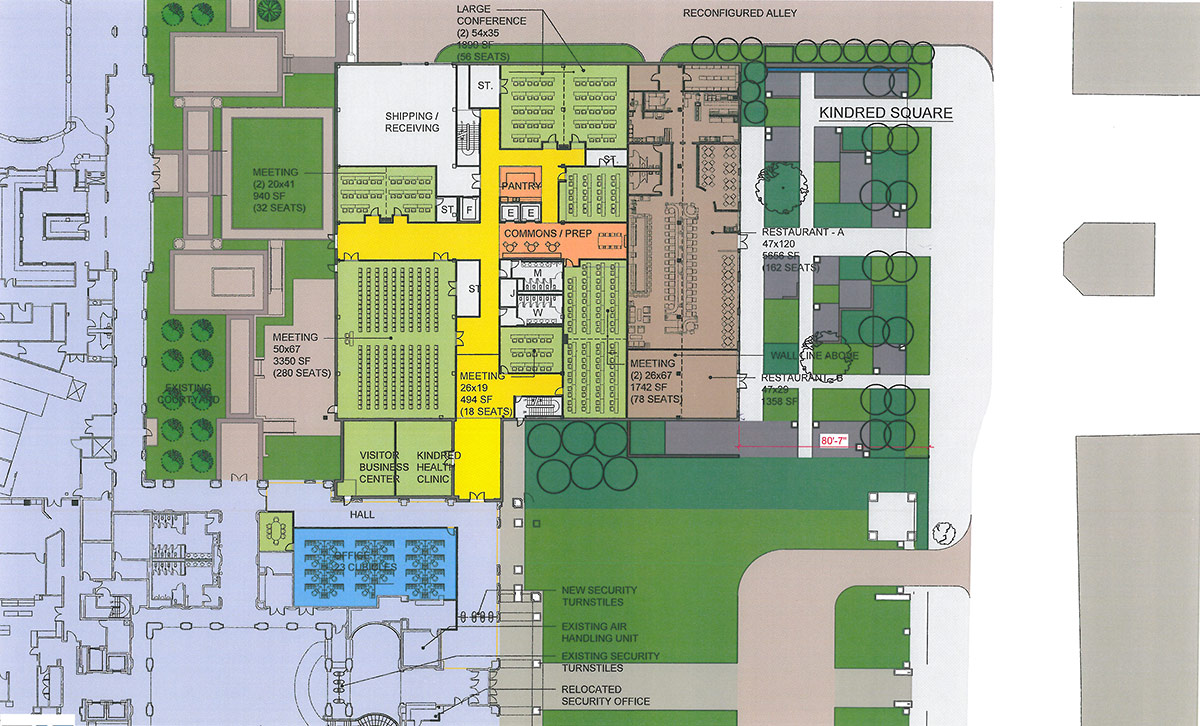

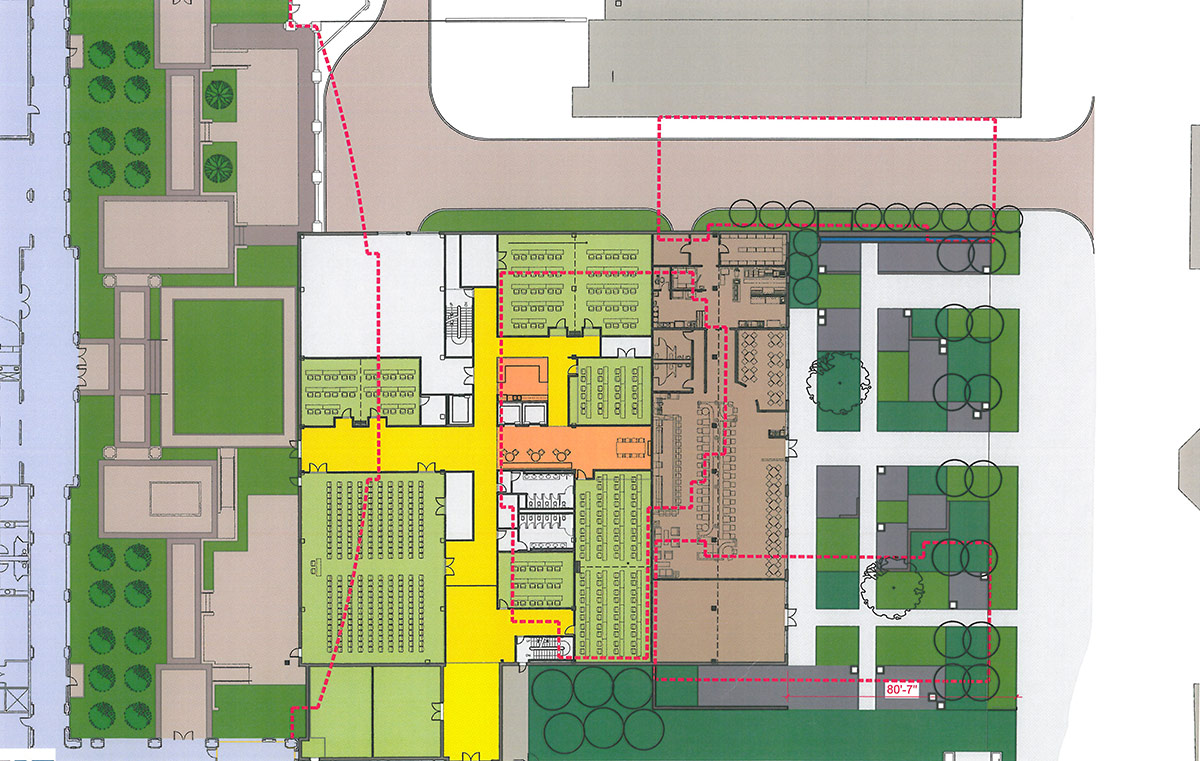

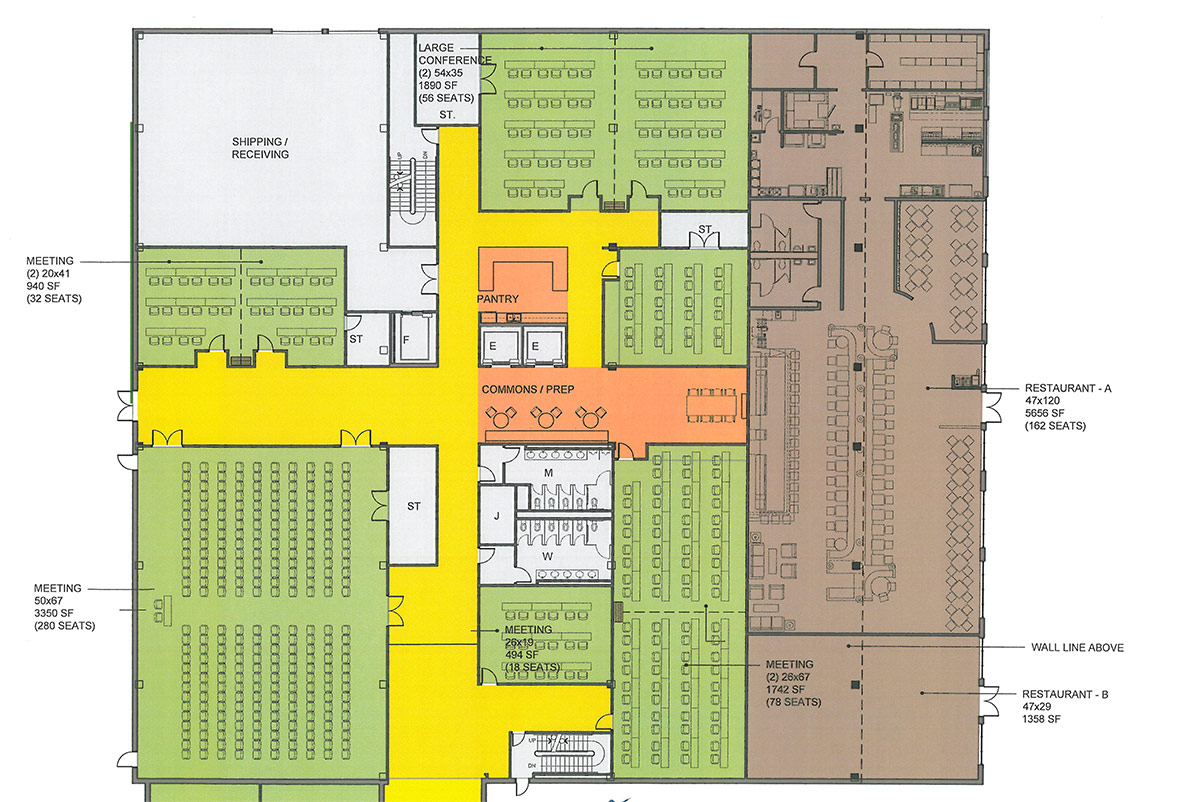

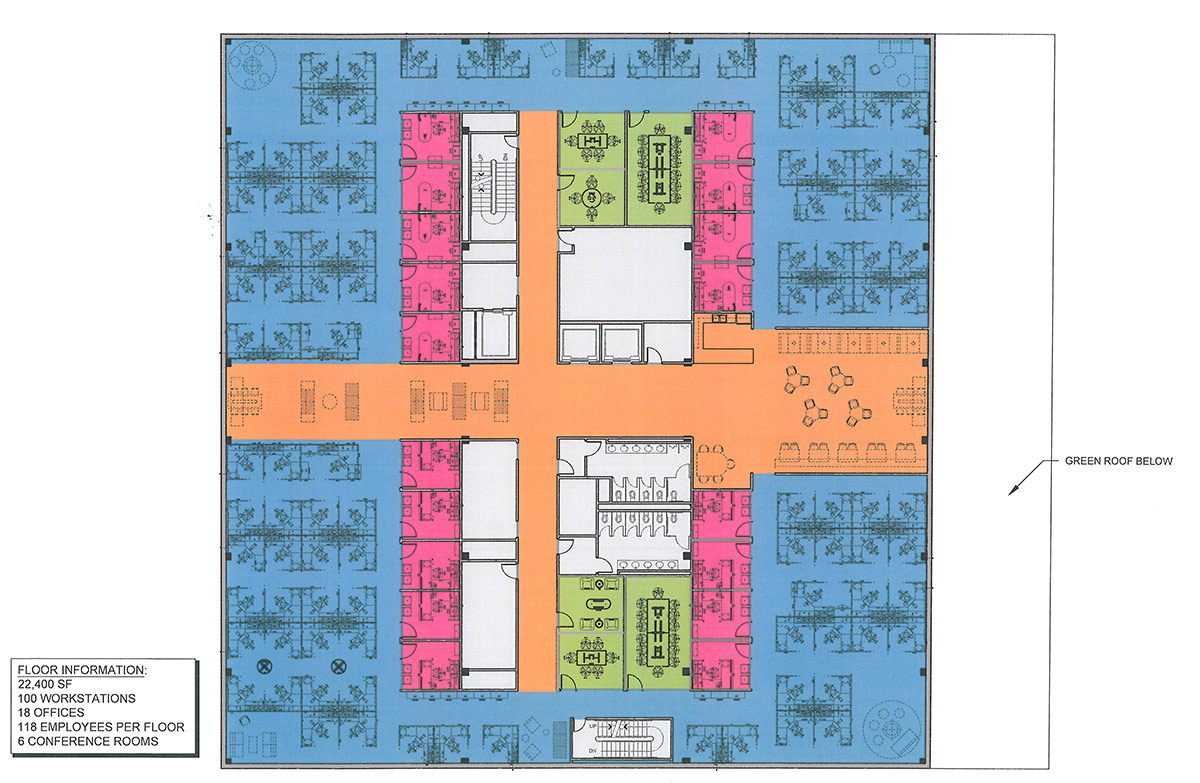

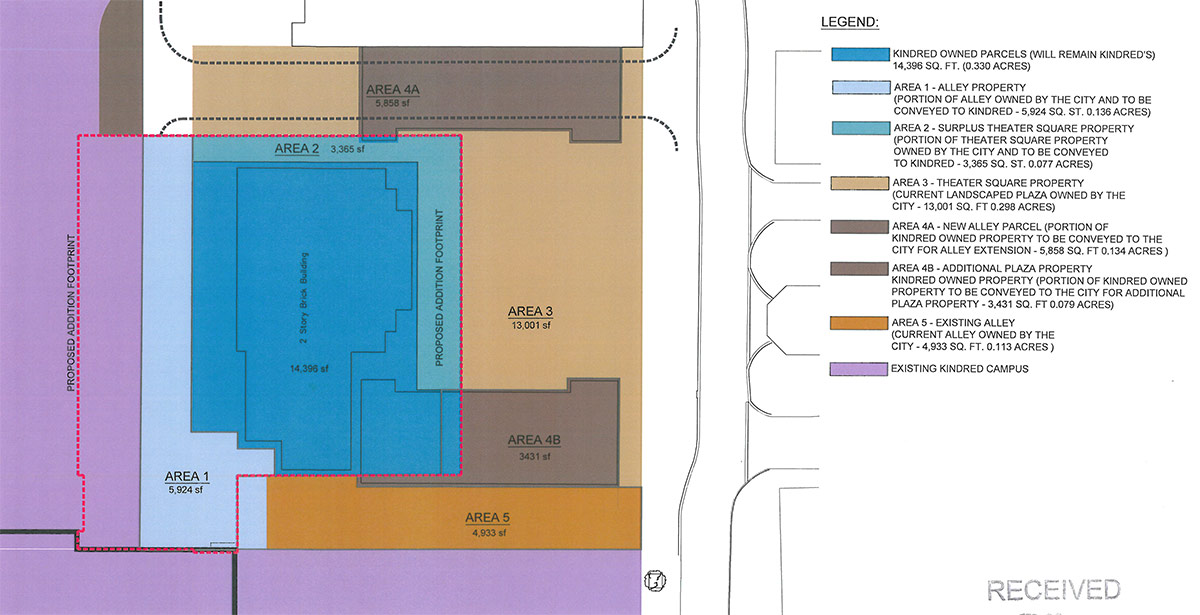

Kindred’s proposed $36 million six-story building would cover 142,000 square feet on a 1.1-acre site. The structure would replace Theater Square’s two-story, U-shaped commercial structures and take up a portion of the city-owned plaza. Kindred purchased the north and south Theater Square buildings from FBM Properties the western building from FMEE Properties last year.

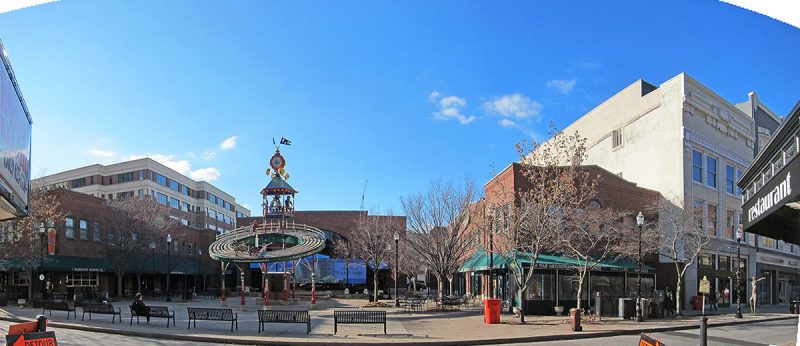

Current tenants at Theater Square—the Bluegrass Brewing Company and Yafa Cafe—would vacate their spaces as part of the expansion project. Kindred has not announced whether the retailers would return in the new building, but it’s likely they would wait for 18 to 24 months of construction to reopen. The whimsical Louisville Clock by sculptor Barney Bright will also be moved to an undisclosed location, likely inside due to recent vandalism. The city-owned clock was restored and installed at Theater Square in 2011.

The new building has been designed by local architecture firm K. Norman Berry Associates, which has distinguished itself with high profile projects like the elegant infill Fenley Building and the 21C Museum Hotel, both on West Main Street. The firm’s design this time is a largely generic box clad predominantly in brick with an aluminum storefront system at ground level enclosing 7,000 square feet of retail space set aside for two restaurants. The main building massing steps back around 25 feet from the single-story retail base and a small green roof is included in the design. The building will stand 86 feet tall, or 97 feet to the top of its rooftop mechanical space.

“Kindred Square” would replace Theater Square and would include “alternating panels of pavers, sods and perennials.” with moveable furniture placed throughout. At the northern side of the plaza, a large waterfall would mask a new service entrance into the site, connecting with an existing alley.

According to the development announcement, the new building would house support center operations, the company’s national training center (called Kindred University), and an employee wellness clinic. It would serve as a sort of national training hub for Kindred, and employees from across the country would pass through. Kindred already employs 2,500 people in Louisville. Pending this week’s hearing and other approvals, the project could be completed in 2017.

As is unfortunately the case with just about every development proposal these days, a large portion of the budget comes from public subsidies. The structure will cost an estimated $36 million, but a hefty portion of that is covered by subsidies in the form of performance-based tax breaks for creating jobs. Up to $11 million in incentives would come from the Kentucky Economic Development Finance Authority (KEDFA) through its Kentucky Business Investment program. That agency is also providing another $500,000 through the Kentucky Enterprise Initiative Act. (That’s 32 percent of the entire project budget.)

Kindred’s predecessor company, Vencor, proposed a sculptural I.M. Pei–designed tower along the waterfront before going into bankruptcy.

History Loves a Wrecking Ball

Before we evaluate the current proposal, let’s look back at the site’s history to better understand its evolution over time.

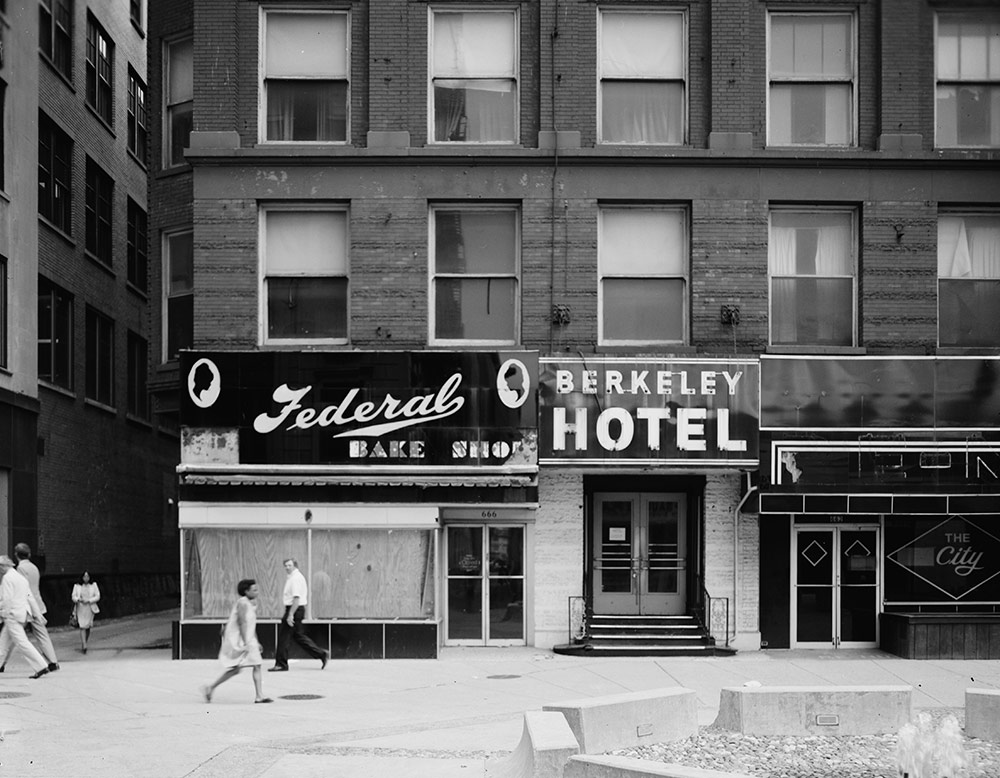

The modern era of Fourth and Broadway began in the 1920s when the predominantly residential area was being rebuilt as a dense and thriving city core. By 1927, Louisville contained some 235,000 residents, making it the 34th largest city in the country, and Fourth and Broadway was bustling. The Brown Hotel was built at break-neck speed in 1923 by architect Preston Bradshaw. Across Broadway, the 17-story Heyburn Building was finished in 1928, bringing with it a modern skyscraper aesthetic that emphasized the structure’s vertical elements. The corner was quickly becoming the heart of the city, earning the nickname, “The Magic Corner.”

On the northwest corner, the four-story Martin Brown Building also designed by Bradshaw replaced a fire-ravaged dance hall in 1927. The structure brought with it streamlined Art Deco detailing in its limestone facade—Louisville’s only example from that time period—along with enormous windows that must have flooded its office space with natural light. The structure was built by wealthy businessman J. Graham Brown and named after his late brother, Martin.

The sturdy four-story Martin Brown Building got a lot taller in 1955 when the Commonwealth Life Insurance Company added another 17 floors to the building—for a total of 21—making it the city’s tallest at 255 feet. The renamed Commonwealth Building at 680 South Fourth Street stood until January 16, 1994, when it was imploded due to the cost of renovating the building.

Commonwealth Life Insurance Company created the Capital Holdings Company in 1969, becoming its subsidiary and eventually building another skyscraper, the Capital Holding Center, aka the Aegon Tower or 400 West Market.

Theater Square

The Theater Square we know today was the result of a 1985 public-private partnership “between the city, state, a labor pension fund and five local corporations and banks,” according to Metro Louisville. A $45 million campaign to revive the corner of Fourth Street and Broadway was launched. Called The Broadway Renaissance, the initiative built Theater Square, reopened the Brown Hotel, and constructed a large parking garage north of the hotel. It also saved the Kentucky Theater and a small portion of the old Ohio Theater facade. Work continued into the 1990s, according to Metro Louisville:

In 1995, efforts to revitalize the area continued with renovations to the Palace Theatre, Theatre Square, and surrounding restaurants. Fourth Avenue was reopened to vehicles while the development of the surrounding Theatre Square entertainment and business complex were completed. Current restaurants along Theatre Square include: Sapporo, Theater Square Marketplace, Safier Mediterranean Deli, and Bluegrass Brewing Co.

But before Theater Square, this stretch of Fourth Street was once the home of a pair of stately buildings, including the five-story Berkeley Hotel and an adjacent four-story structure. A lot of history has gone missing from this once-magnificent intersection. The set of buildings here created a well-defined urban edge along the sidewalk and if they were around today, would have made great candidates for adaptive reuse as offices of housing. The density Theater Square today provides pales in comparison to what the block once offered.

The New Modern Era of Fourth & Broadway

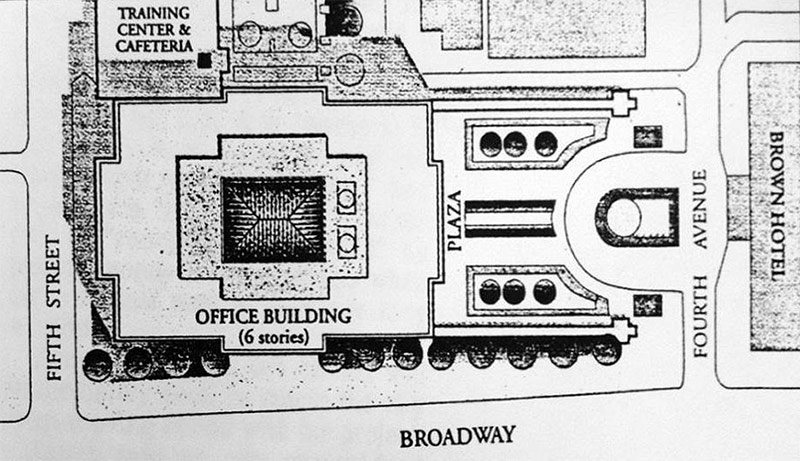

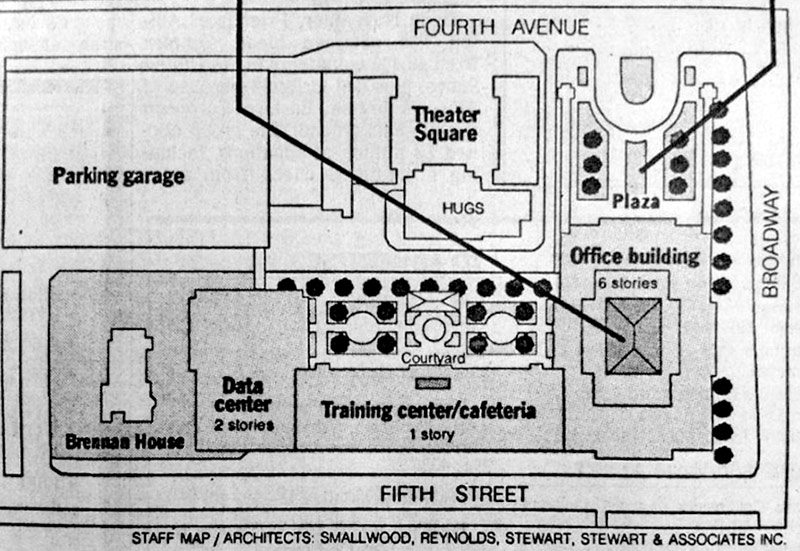

The current six-story Kindred headquarters was completed in 1992 as a complex for Capital Holding. The company had purchased the Commonwealth Building and its adjacent garage in 1990 for $9 million. The city chipped in $1.9 million of that figure. Atlanta-based architecture firm Smallwood, Reynolds, & Stewart designed the beige and red brick building.

Those plans called for a large circular driveway at the site of the Commonwealth Building under guise of a park. The developers at the time called the driveway a “front porch” for the Brown Hotel. Today, that front porch is more accurately the front parking lot as the Brown uses the sidewalk here to park cars, rendering it nearly impossible for handicap people to pass through.

Kindred acquired the Capital Holdings complex in 2006, taking over the buildings for its own use.

While the large office building is the most prominent on the site, it’s footprint is actually less than half that of the overall complex. Along Fifth Street running north from Broadway, a large one-story training center and cafeteria turns its back to the street, creating an enormous dead zone along Fifth that’s only exacerbated by an equally dead facade at the Courier Journal‘s facility across the street.

What Does Metro Planning Really Think?

Metro Planning & Design reviewed Kindred’s proposal against guidelines established to create quality urban development in the Downtown Master Plan and against Louisville’s Land Development Code, Cornerstone 2020. A preliminary report posted on Metro Louisville’s website last week included an incendiary review of the project as “suburban” and establishing a bad precedent for future development with its setback from Fourth Street. A final report released today was scrubbed of such language, instead lauding the proposal for creating additional green space.

According to the city’s final report, “the established urban pattern of the 4th Street wall to create the Kindred Plaza will be diminished., thus contradicting Cornerstone 2020’s goals for the Downtown’s future development.” The report noted that 89 feet of streetwall will be lost.

The report also added to the preliminary findings that Kindred is moving its building closer to the street than the westernmost Theater Square building. The new building’s one-story retail base will sit 80 feet from the streetwall, approximately 20 feet closer than Theater Square, but it’s main building mass steps back from the first floor by about 25 feet, meaning the main building effectively sits over 100 feet back from Fourth Street.

The final report steps back from accusations that the planned addition will be anti-urban. The preliminary report included this scathing analysis of the Kindred design that was later removed:

The design, as proposed, is creating an internally oriented and secured “campus” environment, disconnected from the street and pedestrian environment, with an inward focus. Exclusionary and static, a suburban design is being proposed in an urban environment, neglecting to engage with its surrounding buildings and the historical importance of 4th and Broadway, contradicting the goals set forth by the 2020 Comprehensive Plan.

Due to the project’s proposed disconnect from the pedestrian environment, Staff is concerned the plaza will not function as presented and will not successfully engage the public. Staff is also concerned that if an exception is made in this case, and that the project is approved as proposed, precedence is being set and will encourage future developments to not meet Land Development Code, giving further opportunities to deteriorate the urban environment.

Instead, the final report praises the new plaza as “valuable public open space” claiming that it will, in the end, “offset the loss of the street wall.” The final report does call for careful attention to the plaza’s design to promote urban interaction.

That revision of the staff report seems hollow at best, as it’s clear that this plaza won’t contribute in a meaningful way to the quality of Fourth Street—on the contrary it will in fact erode its urban qualities further.

While Theater Square wasn’t perfect by any means, it did wrap its plaza with three sides of retail frontage, standing two stories tall to give the space definition. Existing mature trees add to the scale of the square. Kindred’s new plaza will be undefined and inevitably soulless, with a giant waterfall to mask a service truck entrance that appears on plans to actually be wider than Fourth Street. The landscaping as proposed appears to create a sort of green moat that cuts the sidewalk off from the proposed restaurant space. It reads more as a buffer to pedestrians for an overscaled restaurant’s outdoor dining area than a real public plaza. Further, the one-story retail podium diminishes the space’s overall definition as an urban plaza.

But beyond all of these reasons why the plaza is not needed and is harmful to the city’s fabric, there’s already a faux-plaza directly to the north that Kindred uses as a gated, landscaped, wrap-around driveway for its main entrance—some 175 feet off of Fourth Street. (It’s sidewalk facing entrance along Broadway has been locked for years with a note telling people to walk around to the gated entry.) Removing Theater Square and opening up the new plaza to this larger gated driveway completely erodes a corner that was once anchored by Kentucky’s tallest building.

I asked Jessica Wethington, spokesperson for Metro Louisville’s Develop Louisville, about why the final language was watered down from the preliminary report, but she said she could not comment on pending cases. She did provide the following comment:

The guidelines are not intended to discourage development, but to encourage development which is innovative and aesthetically pleasing in design. A development proposal that does not conform to one or more specific guidelines may be approved if it is determined that the proposal is in conformance with the intent of the guidelines considered as whole. And staff has recommended approval for the project.

Both the preliminary and final staff reports did recommend approving the project with a series of conditions, including trying to save a portion of the southern Theater Square building that comes up closer to the sidewalk, adding a new structure in its place, redesigning the plaza for better pedestrian flow, and requiring future development to conform to the city’s code, potentially being built up to the corner of Fourth and Broadway.

The DDRO Committee will take up the case this Wednesday, March 11, 2015 at 8:30a.m. in the Old Jail Building Auditorium (514 W Liberty Street)—and we hope that body will take a strong stance on how the urban pattern will affect the city going forward. Louisville deserves a voice in this development, especially when 32 percent of the entire project budget is coming from public funds.

Wethington said the case may also require going before the Board of Zoning Adjustments or another planning committee, but that the project does not need Metro Council approval to proceed. Kindred and the Mayor have previously said the building could open in 2017.

[Image from UL Photo Archives, Reference, Reference. Hat tip to WDRB for finding the final report.]

Thank you for this excellent coverage. Am I correct that the take-home message is that Metro has watered-down the initial report, and then simply asked Kindred to “do better next time?”

Both reports generally came to the same conclusion in the end: approve the project with token conditions. The prelim report just worded itself in a way that read that pointed out the problems with the design. (And read like the agency didn’t believe the project should move forward but it had to approve it anyway. The final report reads like someone wanted the first rewritten.) Either way, the conclusion is the same.

In which case, what is the point of a review? Token suggestions accomplish nothing, except establish a pattern of weakness, desperation, and inferior aspirations. Louisville is better than this. We know what needs to be done. Now let’s do it.

Between this and the Broadway Wal-Mart it certainly feels like Cornerstone 2020 was less of a Cornerstone and more of an eroding plaque on said cornerstone with words to the effect: “Will sell out our principles to bidders with enough cash. Inquire within.” At least in the case of Wal-Mart we can blame an exterior cartel for bullying us. With Kindred we just seem doomed to never learn from the mistakes of the past (Capital Holdings, Vencor). If history repeats itself: Kindred mostly demolishes Theater Square, leaves it an eyesore, then “goes bankrupt”, reforms as a new company with a new ridiculous name and blames the entire ordeal on Metro and expects the tax payers to bail out their wanton demolition projects…

This is tough to see happening. I will be the first to advocate investment into downtown, and the expansion of Kindred is no doubt a great thing for the Louisville job market, but this part of downtown? The theater district is one of the few organic developments in the downtown market. It hasn’t been forced upon us like 4th Street live or to a lesser extent NuLu and Main Street. Its built on quality entertainment, in historic venues, supported by quality hospitality. Why water that experience down with some expanded corporate headquarters that doesn’t fit the area? I can point to to several parking lots within a two block radius that could be used for this expansion. I would be more supportive of a Kindred expansion in the area if their current office space was more fitting for the area, but if past behavior is an indicator of future behavior, I think we know what to expect with this development.

As one of the few young 25 year-olds in this city that has made a concerted effort to live downtown, despite swimming upstream when it comes to city support, I am upset to see a great restaurant and square be erased for a corporate headquarters.

I agree, Jon. The existing Kindred property is the first place I would have looked for determining an expansion site – saves millions in property acquisition right off the bat. In my perfect world, the expansion would have happened on Fifth Street, where the Kindred cafeteria and private courtyard now stand (see site plans above). This stretch of 5th is depressingly bleak because the hundreds of feet of street frontage at the CJ and Kindred turn their back to the sidewalk. Activating that part of 5th, perhaps with a pedestrian connector to Fourth Street, and adding retail would have fixed the planning mistakes from the early 90s when the building was built and helped to expand the 4th Street area without plopping a suburban office park building, 100 feet off the street wall.

City of the 70’s indeed.

The fact that the Mayor calls this a “dream come true” just shows the horrible mindset that has held Louisville back for so many years. Downtown Louisville needs infill maybe more than any downtown or city center I’ve ever been to. Now they are going to tear down one of the few successful pockets of downtown for this nightmare? It’s honestly amazing to me how much of Louisville’s existing advantages have been simply destroyed for parking lots and surburban style buildings in the last 60 years. I don’t want to keep business out but there are so many vacant lots where this could be built in downtown.

It’s honestly things like this that me feel great about my decision to leave Louisville. It’s a city trying to catch up to the ideals of the 1950’s and 60’s that no longer apply in today’s world. It is so frustrating because I do love the city and know what it could be (and once was).

Looks like its just going to be turned into a glorified break room/smoking area for the workers in that building now.

I’m trying to get out myself.

Branden — Why would Kindred not simply expand on its existing property, as you suggest? The existing gated courtyard seems like it could have been the perfect place. I don’t understand the cost advantage of acquiring and demolishing existing structures when open space is already available. What are the motives here?

Also, is there a role for Metro to get more intimately involved in projects such as these from the get-go? Kindred’s expansion is a huge win for Downtown (when will Yum, etc. follow suit?). That said, can’t a part of Metro’s “subsidy” be planning and design work that suits BOTH Cornerstone 2020 AND Kindred? Why can’t this be a team effort? Why are we so passive?

Until Louisville has intelligent, competent leadership nothing will change for the better. There is no hope under this mayor.

I’m not sounding any alarms over this. Let’s take the greenspace on 4th St across from the Convention Center. It think that space is rather a propos. NuLu will meld well into the downtown area once the bridge and streetscaping is completed. The Omni will provide good infill,and the other hôtels and bourbon distilleries (Whiskey Row, included) will make for interesting dynamics. I don’t think downtown is far off track. Big, glass, steel towers, which seem to be en vogue elsewhere, is not my cup of tea.

The problem is that these questions have already been settled by Cornerstone 2020, which was ratified fifteen years ago. After much work and collaboration, Louisville decided what it wanted itself to look like in 2020. Now, we just have to follow those guidelines. This project doesn’t fit the bill. It’s pretty simple, in my mind.

Wow. What a severe step backwards for the revitalization of the 4th street corridor… I’m astounded. Absolute design blunder on all levels.

Branden, as always, this is a detailed, thoughtful, well-researched expose. Where is the architect’s responsibility in these discussions? I have sat in meeting after meeting with architects for developers–most recently over a suburban strip mall design for my urban historic neighborhood–and they actually seem to think they are gifting us with their inappropriate, insipid design. They are a consultant for their client and presumably are implementing their client’s vision, but why would that be inconsistent with creativity? What gives?

Leslie you don’t know many architects do you. They’re either poor and free or they are slaves to their clients. We get ugly buildings because of ugly clients. That’s how it works. And this building is a turd. Even worse is this turd seeks to replicate the damage placed in 5th Street. Louisville makes no sense.