[Editor’s Note: This is the second in a multiple-part series about street safety in Louisville as the city continues to roll out its three-year pedestrian safety campaign, Look Alive Louisville. This section examines just how dangerous our streets are today across the country and at home. View the entire series here.]

Today, the curb is a dividing line between the realm of the pedestrian and that of the motorist. Except for a few certain times when we’re “allowed” to enter the street—either a few seconds when the crosswalk light turns or for a few hours during CycLOUvia or another street festival—streets are for cars. They’re built for speed, for moving motorists as efficiently as possible, and for absorbing driver error—remember those trees the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet keeps wanting to remove so drivers don’t hit them?

As a pedestrian, that feeling of panic when crossing a busy street is quite intentional—the automobile lobby in the 20th century worked very hard to redefine how we view our most prolific public space: the street. And, in turn, to shift cultural underpinnings about who streets are for.

https://youtu.be/NINOxRxze9k

A century ago, cars were still relative newcomers on American streets dominated by electric trolleys, horse-drawn carts, bicyclists, and, of course, pedestrians. Before cars were mainstream, streets were more like public promenades—albeit often muddy and dirty ones—where the pedestrian was king (as the video above of San Francisco circa 1905 attests).

Before 1915, there was no such thing as “jaywalking”—the term invented exactly a century ago and popularized by the automobile industry. (The term translates roughly to “inexperienced walker” and it had a twin, “jay driver,” that never caught on.) Crossing the street meant walking any which way one could imagine.

An in-depth article in Collectors Weekly investigated early street culture:

For those of us who grew up with cars, it’s difficult to conceptualize American streets before automobiles were everywhere. “Imagine a busy corridor in an airport, or a crowded city park, where everybody’s moving around, and everybody’s got business to do,” says [author Peter] Norton. “Pedestrians favored the sidewalk because that was cleaner and you were less likely to have a vehicle bump against you, but pedestrians also went anywhere they wanted in the street, and there were no crosswalks and very few signs. It was a real free-for-all.”

Roads were seen as a public space, which all citizens had an equal right to, even children at play. “Common law tended to pin responsibility on the person operating the heavier or more dangerous vehicle,” says Norton, “so there was a bias in favor of the pedestrian.” Since people on foot ruled the road, collisions weren’t a major issue: Streetcars and horse-drawn carriages yielded right of way to pedestrians and slowed to a human pace. The fastest traffic went around 10 to 12 miles per hour, and few vehicles even had the capacity to reach higher speeds.

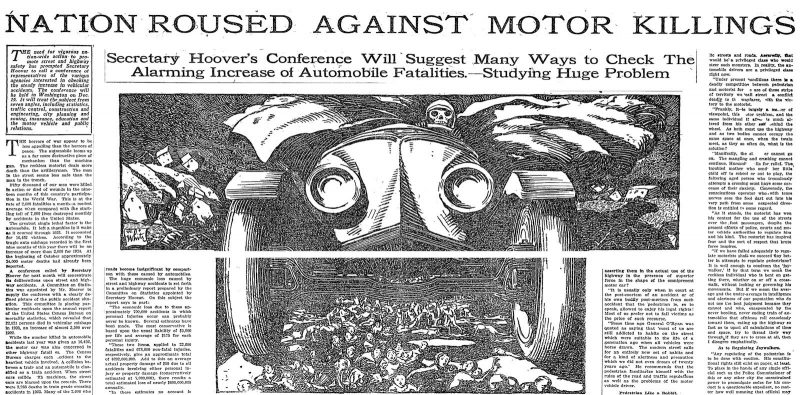

According to Roman Mars at 99 Percent Invisible, the motorist of the early 20th century was always at fault when traffic violence occurred. Mars cited the New York Times, November 23, 1924 when crashes were skyrocketing:

The horrors of peace appear to be [more] appalling than the horrors of war. The automobile looms up as a far more destructive piece of mechanism than the machine gun. The reckless motorist deals more death the artilleryman. The man in streets seems less safe than the man in the trench. The greatest single lethal factor is the automobile. It left shambles in its wake as it coursed through 1923.

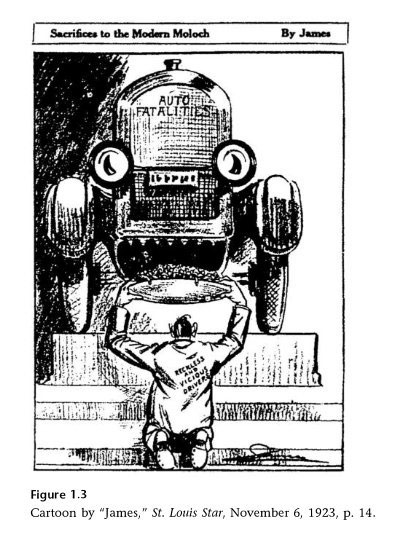

As backlash toward these destructive new automobiles grew in the face of rising death tolls, something had to give. According to the essay “Street Rivals: Jaywalking and the Invention of the Motor Age Street“:

Before the American city could be physically reconstructed to accommodate automobiles, its streets had to be socially reconstructed as places where cars belong. Until then, streets were regarded as public spaces, where practices that endangered or obstructed others (including pedestrians) were disreputable. Motorists’ claim to street space was therefore fragile, subject to restrictions that threatened to negate the advantages of car ownership.

Epithets—especially joy rider—reflected and reinforced the prevailing social construction of the street. Automotive interest groups (motordom) recognized this obstacle and organized in the teens and 1920s to overcome it. One tool in this effort was jaywalker.

Motordom discovered this obscure colloquialism in the teens, reinvented it, and introduced it to the millions. It ridiculed once-respectable street uses and cast doubt on pedestrians’ legitimacy in most of the street. Though many pedestrians resented and resisted the term and its connotations, motordom’s campaign was a substantial success.

This rebranding effort continued well into the 20th century, and its legacy can still be seen all around us today, as you’ll see later on. Vox’s Joseph Stromberg noted:

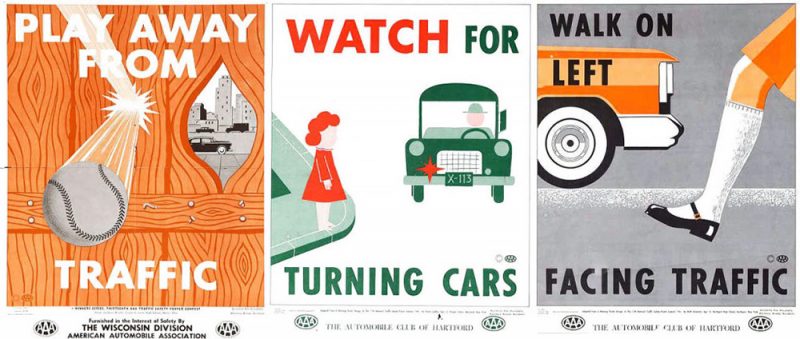

AAA began sponsoring school-safety campaigns and poster contests, crafted around the importance of staying out of the street. Some of the campaigns also ridiculed kids who didn’t follow the rules — in 1925, for instance, hundreds of Detroit school children watched the “trial” of a twelve-year-old who’d crossed a street unsafely, and as Norton writes, a jury of his peers sentenced him to clean chalkboards for a week.

This was also part of the final strategy: shame. In getting pedestrians to follow traffic laws, “the ridicule of their fellow citizens is far more effective than any other means which might be adopted,” said E.B. Lefferts, the head of the Automobile Club of Southern California in the 1920s. Norton likens the resulting campaign to the anti-drug messaging of 80s and 90s, in which drug use was portrayed not only as dangerous, but stupid.

If you’re interested in this early evolution of the street, it’s worth spending some time looking through this article from Gothamist, this podcast from 99 Percent Invisible, this history from Vox, this article from Salon, and this longread from Collectors Weekly to learn more about the fundamental changes to the character of our streets that happened over the 20th century.

The history of the street and public space are important for understanding where we are today in the ongoing battle for street safety. Louisville is in the midst of a three-year pedestrian-safety campaign under the banner of Look Alive Louisville. Learn about that effort in the first part in our ongoing series on street safety in Louisville.

By 1926 in NYC, things were already much worse for the pedestrian. 😉 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lkqz3lpUBp0